China’s challenge to the West in 2021 and beyond

This year marks the centenary of the founding of the Communist Party of China. By its end, Beijing wants to have built a “moderately prosperous society.” In parallel, President Xi Jinping seems ready to embark on an all-out systemic competition between China and the West.

In a nutshell

- China stands as the world’s best hope for driving economic recovery

- Statist China and the West are in a ruthless, all-out race to the top

- However, the Middle Kingdom is hung up by structural weaknesses

For Beijing, 2021 will be defined by one of the “100-year plans” extolled by President Xi Jinping, who is also the head of the ruling Communist Party of China. That is, by the centenary of the CPC’s founding, in 1921, China should have become a “moderately prosperous society.”

Also, this is the first year of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan. But I hold that 2021 marks, above all, the time when China’s marathon race against the United States begins in earnest. According to Mr. Xi’s original concept, that race was to end in 2049, the centenary of Mao Zedong’s (1949-1976) seizing power. What we are witnessing now is an acceleration, the start of an-all out phase of the contest between macroeconomic players: statist China and the West. President Xi has never publicly extolled his country’s “socialist” approach as vehemently as he does now.

The West may not have fully grasped yet what China is up to. However, Beijing’s latest policies indicate that the Chinese political elite is intensely concerned with the systemic competitive pressure of the most recent years. Winning the contest is now the top priority on Beijing’s agenda. It matters to Mr. Xi that the historic race begins this year, as China has lunged out first from the starting blocks.

Based on China’s performance in 2020, a brief analysis of its macroeconomic trends this year casts some light on how this race will shape up.

The 2020 surprise

In February and March of 2020, most projections for China’s economic performance were pessimistic. This was due to a worsening trade dispute with the United States and a sharp economic contraction caused by the outbreak of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, things have turned out much better than expected. China apparently emerged first from the pandemic and now stands as the world’s best hope for driving economic recovery in 2021.

Facts & figures

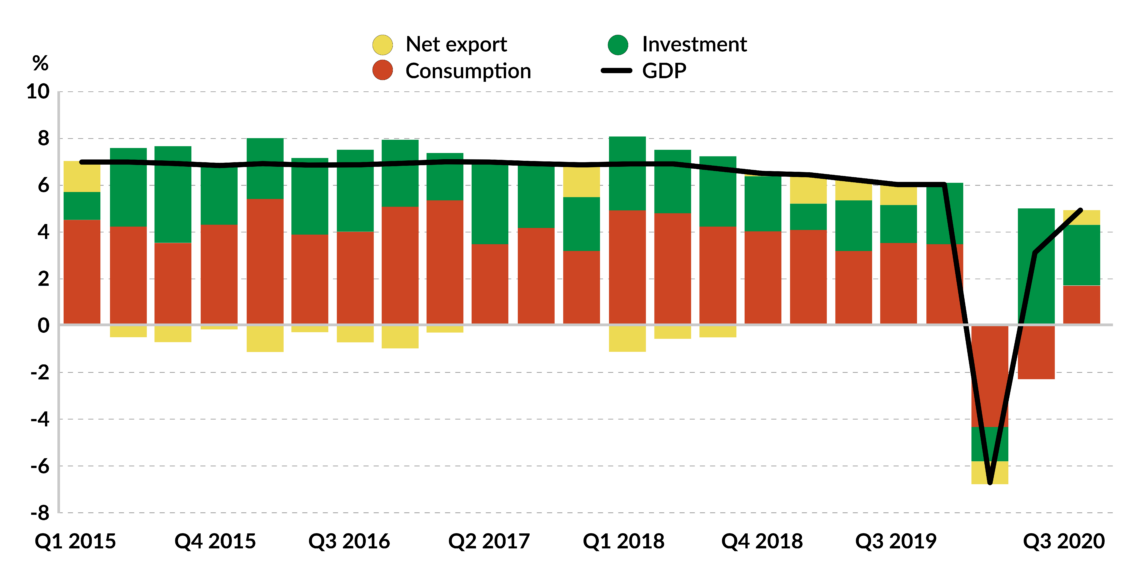

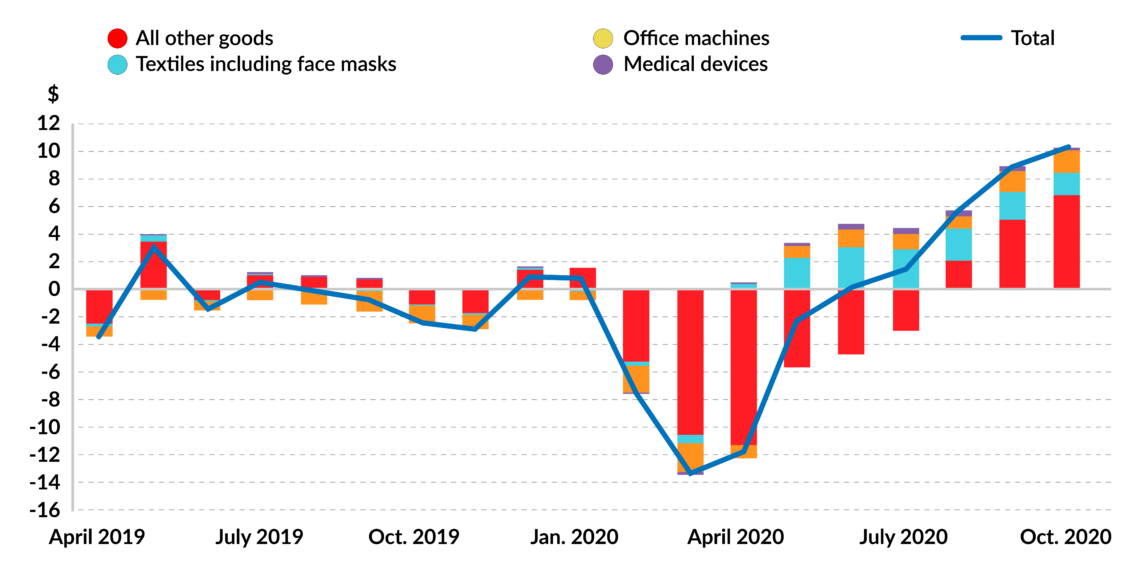

Its economy experienced a sharp rebound last year, with a gross domestic product (GDP) growth of over 2 percent, at the time when the rest of the world languished in negative territory. Three surprising developments are worth noting. First, China’s exports surged despite the pandemic and U.S. sanctions, contributing 16 percent to global export trade in 2020, more than in previous years.

Facts & figures

Along with the growth in exports, currency reserves have grown significantly: at the end of December 2020, China’s foreign exchange reserves stood at $3.217 trillion vs. $3.108 trillion in 2019 (data from China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange is here and here).

Secondly, China’s foreign capital utilization achieved a rare counter-trend growth in 2020, a 6.4 percent year-on-year jump from January to October, with double-digit growth recorded in recent months (according to a data release from the Ministry of Commerce on November 16, 2020). This result is closely related to the appreciation of the yuan. And thirdly, the yuan has appreciated against the U.S. dollar, so it attracted foreign buyers to purchase more than 1 trillion yuan worth of Chinese stocks and bonds.

Facts & figures

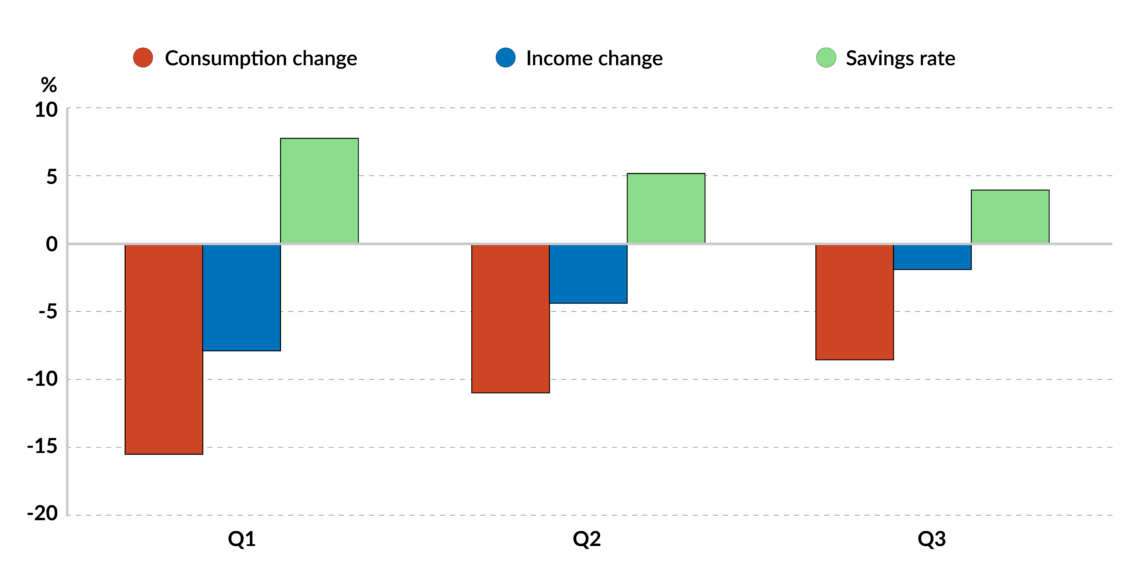

The troika driving the Chinese economy – exports, investment and consumption – did not perform in lockstep last year. Compared to the first two, consumption was still negative overall but picked up in the second half of the year.

Shifting economic gears

China’s economy outperformed all other major economies last year, but its leaders remain cautious. They are aware that many of the country’s economic problems remain unsolved. Also, Donald Trump’s hard-nosed China policy has forced President Xi to ditch his scheme for advancing China by working closely with the U.S. Beijing does not have much hope for things turning out fundamentally different under the administration of President Joe Biden.

As a consequence, Mr. Xi and his team have had to make significant adjustments in China’s economic strategy. In my view, these shifts amount to an open declaration of systematic competition with the U.S.-dominated West.

In 2020, after years of talk about shifting from an export-driven to a consumption-driven economy, the Chinese government adopted a “dual circulation strategy” as an economic reorientation. The so-called “domestic circulation” refers to policies aimed at strengthening the control of supply chains and focusing the development on high-tech industries while, at the same time, increasing the national consumption capacity and unleashing the potential of the domestic market. Consumption is supposed to become a significant driving force of the Chinese economy.

Consumption is supposed to become a more significant driving force of the economy.

As for the “international circulation,” the new policy suggests that China remains willing to cooperate with the world’s capital and technology community and let foreign companies earn money in its massive domestic market. Beijing is well aware that to someday outperform others in technology, China must continue working closely with leading Western companies and allow them to reap the benefits of its internal market.

President Xi’s “domestic circulation” is focused on two aspects. On the demand side, China needs to boost the lower and middle-income groups’ income, as these have a higher marginal propensity to consume. On the supply side, the central government promotes scientific and technological innovation, focusing on conquering handpicked cutting-edge technologies. The idea is to ensure the upgrading of the industrial chain on its own.

Mr. Xi is a firm believer in the statist approach. He rejects purely free-market policy in these pursuits. Currently, his vision of state-controlled innovation has taken the form of four “comprehensive national science centers” dedicated to research and development (R&D); their number is poised to grow. Simultaneously, the government wants to make good use of advanced Western technology. Last year, for example, Shanghai became a poster child of expanding “external circulation” by persuading Western companies to build as many as 20 foreign-funded R&D centers in the eastern megapolis. And this will very likely lead to more Western technology “spillover” in the future.

The 2021 window of opportunity

To better understand China’s economic plans, one needs to grasp where the global economy is going, especially in the developed West and Southeast Asian countries.

The pandemic in the West is still spreading. Even if the vaccination programs are rolled out efficiently in developed countries, “herd immunity” in their societies will not be reached until the second half of this year – under the most optimistic scenario. This indicates the earliest possible beginning of an economic recovery in the Western countries. Their demand will remain weak in the first half of the year, except for medical supplies, staple foods and household products.

Take the U.S., which China likes to benchmark. According to Li Xunlei, chief economist at Zhongtai Securities, the total value of American Treasury securities held by the U.S. Federal Reserve in 2020 was already larger than the sum of U.S. Treasuries held by all foreign countries, including Japan and China. And according to the indexes of manufacturing output, the U.S. manufacturing sector has been going downhill for the last four years. Therefore, Beijing estimates that the U.S. will only emerge from the pandemic-induced crisis in the fourth quarter of 2021 and will take four to five years to fully recover economically. Beijing believes that this presents an excellent opportunity in China’s comprehensive competition against the American rival.

China will continue to feast on the post-pandemic country dividend, coupled with increasing consumption and investment.

China’s export spurt in 2020 resulted from strong demand during the pandemic. When the demand for pandemic-related medical supplies surged in various countries, Southeast Asian countries were unable to respond to it due to the spread of Covid-19 among their populations. China turned out to be the only producer capable of filling Western countries’ supply gap. It is generally estimated that Southeast Asia will conquer Covid-19 and resume production in the second half of 2021. At that point, the share of exports that were temporarily diverted to China will return to them.

In any case, as a baseline scenario, Chinese economists project the country’s exports and imports in 2021 to rise by 3.0 and 3.3 percentage points, respectively. Due to external factors, exports are bound to show a “high front and low back” trend.

China’s outlook

Based on this analysis, China will continue to feast on the post-pandemic country dividend, coupled with increasing consumption and investment. The market generally expects annual GDP growth to be in the range of 8-9 percent (IMF forecasts 8.2 percent, the World Bank’s estimate is 7.9 percent). Overall, China will retain its position as the fastest-growing major economy in 2021.

The country is gearing up for a significant recovery of consumption this year, with new supportive policies coming in effect. The key areas of focus in 2021 are online shopping and automotive sales.

In 2020, the main investment engines in China were real estate and infrastructure. Looking ahead, real estate investment will slow down, but infrastructure, especially what the government calls “new infrastructure projects” (with high-tech components required), is bound to continue growing steadily in 2021. Several major projects, such as the Sichuan-Tibet railway, the new “land and sea corridor” in China’s western region, new 5G networks and the industrial Internet of things will be launched this year. The growth rate in infrastructure investment may exceed 5 percent, strongly helping the economic rebound. Also, manufacturing investment will be significantly strengthened in 2021.

The 2020 global pandemic has accelerated China’s industrial upgrading and the digital transformation of its economy, with the output and investment growth in high-tech industries significantly higher than that of traditional manufacturing. By my estimate, at least until the third quarter of 2021, global foreign direct investment (FDI) will continue flowing steadily into China.

Statist China and the West have achieved parity in a handful of technologies.

This inflow has already helped relieve the financial bottleneck in investment manufacturing and enabled technological improvement as well as the rapid development of 5G networks. China has built a total of 718,000 5G base stations. With more than 600,000 new base stations to be activated this year, Beijing is pushing hard to develop 5G and its consumer market plus the industrial internet of things.

In 2021, China’s financial market will continue its policy of opening up to the world and wooing foreigners, including Wall Street giants, drawing them to China. (The titans of U.S. finance have a long history of acting as Beijing’s advocates in Washington.) It is expected that China’s direct financing market will gain more room for growth. In particular, the government’s goal of achieving “carbon neutrality” by 2060 means that the green financing sector is bound for rapid expansion. For example, according to the 2019 China Carbon Pricing Survey, the average price of carbon in China’s carbon trading market is currently only 30 yuan ($4.6) a ton. For the price to play a useful role in reducing emissions, it would need to be at least 100 yuan ($15.4) per ton. This tool alone, if used effectively, could open up a promising area of activity for the green finance community and Chinese industry.

Risks and challenges

Great as its opportunities and ambitions may be, China also faces very significant challenges on its development path. Its ultimate success in the economic contest with the West, especially with the U.S., hinges on Chinese leaders’ ability to tackle several complex and multilayered structural problems.

Economic competition is most often reflected in the technological race. Notably, statist China and the West have achieved parity in a handful of technologies. However, it still lags behind the West in high tech overall. President Xi is keenly aware that if the West makes technology transfers difficult, self-reliance will be the only path left for China. It remains to be seen whether China’s ability to invent and apply technology has matured to end its reliance on purloining, forced technology transfers and free-riding. The semiconductor chip industry will prove especially critical.

Beijing is convinced today that whoever controls the industrial internet of things will own the future of the industry. In 2018, it set up a strategic “National Leading Group” to develop that technology. However, the country’s limited chip production capability has proven to be a significant roadblock.

The debt problem, especially the many corporate and government debts, is a time bomb buried in the Chinese banks.

Due to the Trump administration’s export curbs on semiconductors and related equipment, and China’s own decreasing production, chip supply in 2020 remained tight, and prices have risen significantly. This directly affects Chinese electronics exports. Another collateral victim is the country’s auto industry, with nearly 15 percent of its production capacity impaired. Last December, for example, Germany’s Volkswagen plant in China faced a full-line shut down because of the limited semiconductor supply. It can be expected that the chip bottleneck on China’s 5G industrial internet will become even more suffocating.

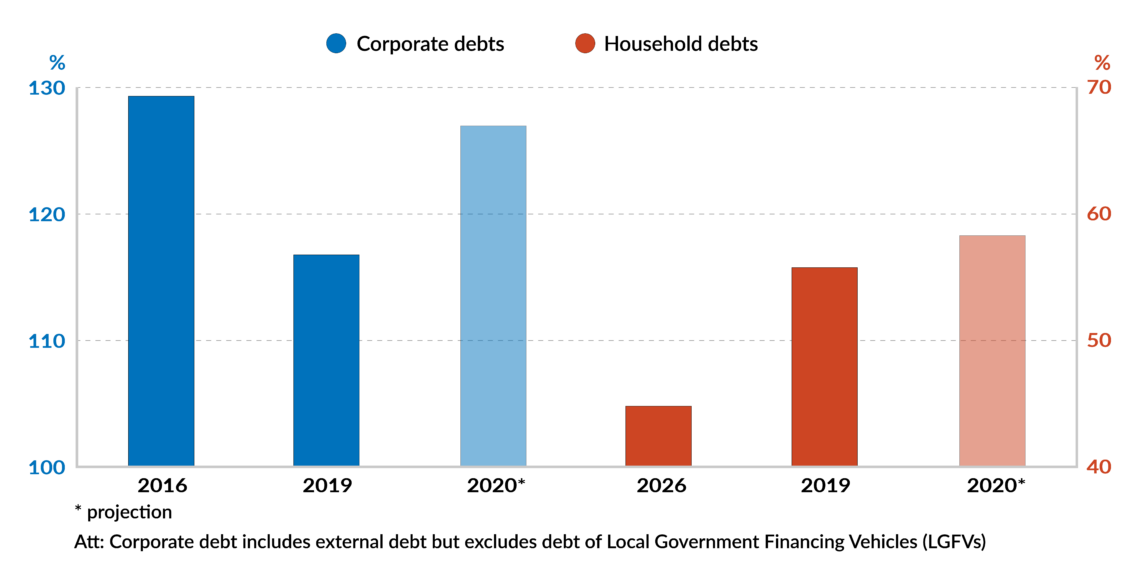

Challenge number two is debt, especially corporate debt and local treasury bonds.

Facts & figures

According to the IMF and other sources, China’s debt ratios soared to record levels in 2020, reaching about 280 percent of the total economy. Corporate debt has risen by about 10 percentage points to 127 percent of GDP in 2020, while household debt was expected to rise to 58.3 percent of GDP, up from 55.6 percent in 2019. China’s local government debt reached 25 percent of GDP by the end of 2020.

Closely connected to corporate and local government debt is the issue of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). It is already part of China’s political economy to stick with the SOEs despite Western accusations that the subsidized sector skews competition in the Chinese and global markets. SOE’s critics have been pointing out that these enterprises, both central and local, are notorious for defaulting on their debts. At the same time, the financing environment for small and medium-sized private enterprises remains difficult.

The debt problem, especially the many corporate and government debts, is a time bomb buried in the Chinese banks.

Scenarios

China’s dividend as the only post-coronavirus economy is still not exhausted. Thanks to this status, its rapid expansion will continue in 2021. China will perform better than other economies. By the fourth quarter, it is likely to have returned to its pre-pandemic level of economic performance.

There are two possibilities for how the Chinese economy will fare in the medium and long term, beyond 2021.

Best Case

At the very best, President Xi’s “double-circulation” strategy, focused mainly on the domestic “circulation,” will bring about a more self-sufficient economy. Coupled with Beijing’s smart use of foreign capital and foreign technologies, China might overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy by 2028 – years ahead of the previous projections.

Worst Case

In the worst-case scenario, Mr. Xi’s statist approach to the economy will backfire, leading to a set of catastrophic failures. To wit: a failure to break through the bottlenecks in critical industrial technologies; a failure to further increase the purchasing power of China’s citizens; a deepening of the gap between the country’s rich and poor; and an unresolved debt problem. In the end, China will find itself stuck in the "middle-income trap” and come short of its ambition to outrun the West economically.

In my assessment, the odds slightly favor China’s success in this historic contest. Muddleheaded Western governments (especially the EU; the U.S. has been rather sober lately) continue to let capital and critical technologies flow into China, giving Beijing a shot in the arm and a chance to develop a competitive edge and strategic advantage. China’s state-controlled, hybrid economy with some elements of the market-driven system might perform well enough if much of the West continue to ignore the alarm bells.