Scenarios for the U.S.-China chip race

The technology race between the United States and China is intensifying. While China has made significant advances in certain sectors, the weakness of its microchip industry is likely to hamper it as the competition unfolds.

In a nutshell

- China is ahead in some technology areas, like AI applications and 5G

- However, it is unlikely to overcome its microchip issues soon

- The U.S. has strong assets - but the race has just begun

In Beijing, political elites are confident that China is now replacing the United States as the global superpower. But when it comes to the technology race, a careful analysis is required to determine who is ahead. Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd recently said that China and the U.S. have never been closer in economic power and technological capacity, and that the 2020s will be a critical make or break period for both Beijing and Washington – a “dangerous decade” for the world.

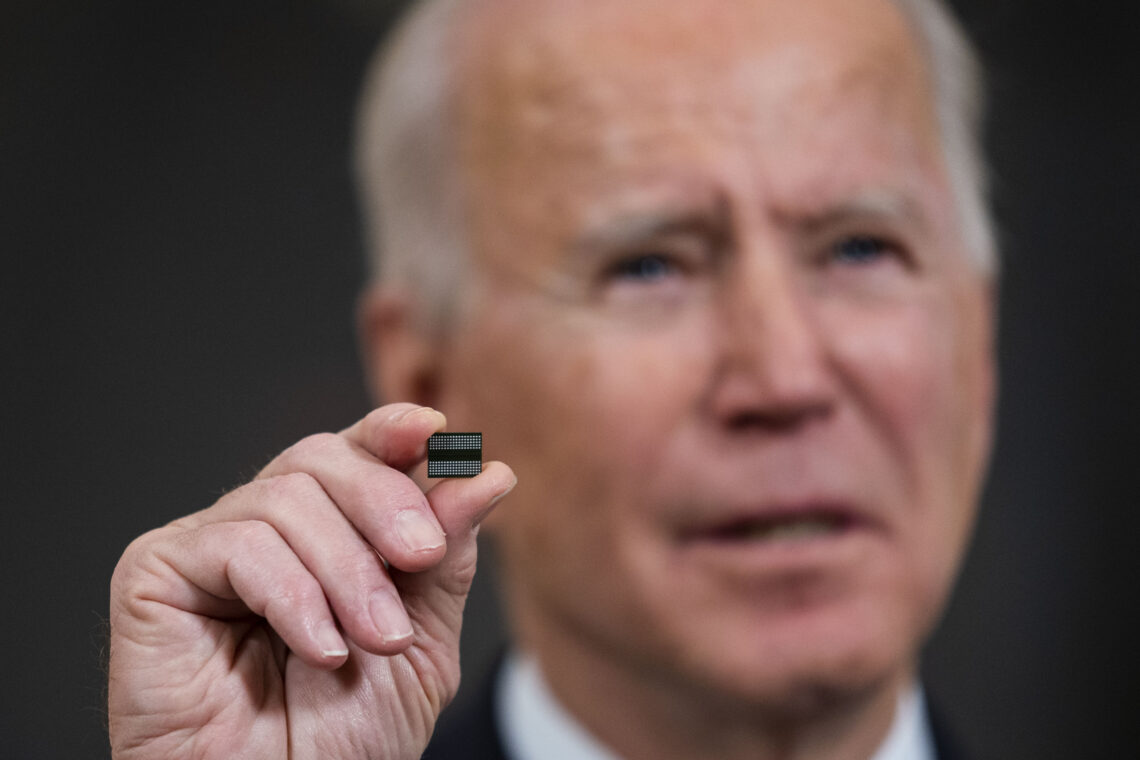

U.S. President Joe Biden has also stated that the two powers are entering a phase of “extreme competition.” And both sides seem to be most concerned about winning the technology race. In China, the drive for technology supremacy in national policies borders on fetishism. In the U.S., the pressure of having to compete with Beijing is felt in every aspect of technological development.

China’s technological capacity

In this race, China is superior in some regards but the U.S. still leads in most sectors. China’s share of global gross domestic product (GDP) increased to 14.5 percent in 2020, up from 9.2 percent in 2010. There are 124 Chinese companies on the 2020 Fortune 500 list, while the U.S. has only 121. In addition, China is both the largest market and the largest supplier in the world. General Motors and Volkswagen now sell more cars there each year than they do in their home countries.

In 2018, the country’s manufacturing value added was upward of $4 trillion – 30 percent of the global figure. China surpassed the U.S. in 2009 to become the world’s top manufacturing nation. But the rate of its manufacturing revenue is only 2.6 percent of the world’s, while that of the U.S. accounts for 12.2 percent.

In some areas, such as 5G, the U.S. is lagging behind.

In 2019, Chinese companies spent $140 billion on research and development, coming second behind the U.S. with $413 billion. However, Chinese spending is increasing at a significantly faster rate than any of its competitors.

China overtook the U.S. as the world’s top applicant for international patents in 2019. It topped the list with 68,720 patent applications last year, a 16 percent increase over the preceding year. In the U.S., the number of international patents filed last year increased by 3 percent compared to the previous 12 months, amounting to 59,230 patents in total. Patents are divided into three categories: invention, utility model and design, with the first category, considered more valuable than the second and third. Most Chinese patents fall in the latter two categories.

In some areas, such as 5G, the U.S. is lagging behind. China’s Huawei filed 5,464 patent applications last year, followed by South Korean tech giant Samsung with 3,093. China also recently surpassed the U.S. in terms of citations in AI-related journals. By the end of 2020, it had 690,000 5G base stations in operation nationwide, compared to some 50,000 in the U.S.

China’s most crippling weakness is in semiconductor technologies, and the issue is unlikely to be overcome in the next five to 10 years. China’s computer chip market accounted for $143.4 billion in 2020, up 9 percent over 2019, making it the largest in the world with 36 percent of the global market. Of this, 60 percent is exported abroad, and another 40 percent is sold locally. But the overall chip industry is still weak: local chip manufacturers in mainland China produced a total of only $8.3 billion worth of chips in 2020, accounting for only 5.9 percent of the Chinese market and only 2.1 percent of the global market share.

U.S. technological capacity

American manufacturing has shrunk greatly due to globalization. For example, the U.S. manufactured 37 percent of all semiconductors in 1990, whereas it makes only 12 percent now. With today’s chip shortage, American manufacturers cannot cope without government support. As for Europe, its manufacturing accounts for less than 10 percent of the global total. Ever since the first round of large-scale globalization, the U.S. has been deeply aware of the urgent need to readjust.

While China produces the largest number of science and technology graduates each year, the U.S. still has the edge in some areas. For example, of the 2,000 best natural scientists in the world, nearly 850 are in the U.S., while only about 260 are in China. The U.S. also attracts talent from all over the world, much more than that in China. In addition, the number of American STEM graduates trained by U.S. universities every year is decreasing, but the Biden administration has vowed to reverse this situation.

China is vastly inferior to the U.S. when it comes to basic research. The Chinese government spent $23.5 billion on fundamental research last year. For comparison, a report by the National Science Foundation found that the U.S. spent $97 billion in 2018, about 17 percent of total U.S. research and development spending.

Adjusting strategies

Under President Trump, “blocking” was the main strategy. Several frontier technologies were placed under an export ban. The screening of foreign investment intensified in 27 sensitive industries and Chinese mergers and acquisitions of American high-tech enterprises were banned. Chinese companies like Huawei and Hikvision were put on a trade blacklist. Finally, since 2018, restrictions on visas for Chinese STEM students apply.

The Biden administration has largely continued Mr. Trump’s deterrence strategy, albeit with some minor adjustments. For example, it intends to implement a code of conduct for technology acquisitions and transactions that was designed by the Trump government. Also, the new administration has relaxed restrictions for SMIC – the largest semiconductor factory in mainland China – on the procurement of equipment and materials, but only for making chips above 14 nanometers. It is unlikely that the U.S. will relax the ban on advanced fabrication below 10 nanometers.

Unlike former President Trump, President Biden is betting on strengthening American technological capabilities and improving competitiveness. To tackle the chip shortage, his administration will need to address two issues: first, how to expand semiconductor production capacity globally (outside China); and second, how to expand production capacity in the U.S. Mr. Biden has begun to talk to Taiwan, Japan and South Korea to establish new supply chains.

However, Washington is also worried about excessive reliance on Taiwan. If China annexes Taiwan by force, it would acquire the research capacity and manufacturing base of Taiwan’s main semiconductor company, TSMC, which would give Beijing a decisive advantage. But even if China does not attack Taiwan, to purchase nearly 90 percent of integrated circuits in East Asia is also a dependence. Therefore, the U.S. is offered $12 billion in investments if TSMC set up a plant in Arizona to revitalize the U.S.’s own semiconductor industry. The president has also sought to invest $37 billion in domestic chip production.

Some Western observers, especially in Europe, appear to be overly impressed by Chinese claims of self-importance.

China’s response to the current situation is reflected in its central planning. Unlike previous plans, this year’s 14th Five-Year Plan also includes a far-ranging vision for 2035. Beijing hopes to achieve “major breakthroughs in key technologies and become one of the most innovative countries in the next five to 10 years.” The document proposes an average annual increase of more than 7 percent in research and development expenditure. It also stipulates that the added value of strategic emerging industries should reach more than 17 percent of GDP from 2021 to 2025. By 2025, 70 percent of chips used in the domestic market should be Chinese-made. The plan also foresees four major science centers and laboratories in sectors like quantum information, photonics, micro-nanoelectronics and AI.

Even if they seem to pursue technology self-sufficiency, Chinese leaders are well aware that domestic innovation is not sustainable without the support of foreign capital and technology. For this reason, Beijing announced it would present a new list of major foreign investment projects this year, which it would support in all aspects. The Chinese government needs to attract investors in advanced technology because its success in the race against the U.S. relies very much on “technology spillover” via foreign companies based in the country.

Scenarios

Some Western observers, especially in Europe, appear to be overly impressed by Chinese claims of self-importance and cast doubts on whether the U.S. can win the race – despite China’s Achilles’ heel. But the situation is more complex.

It is true that China is significantly ahead in the fields of AI applications and 5G, which could lead to advances in quantum computing. But none of this can materialize without high-quality chips. To that end, Beijing has set out a road map that gives its industry eight to 10 years to catch up with Western competitors, eventually breaking through its monopoly and the U.S. export ban. But setting targets and creating a plan does not mean the problem is solved.

The semiconductor industry is globalized and competitive, requiring extensive talent and capital. It is entirely possible that China will progress in the next decade, but the U.S. and its allies’ chips industries will certainly move forward as well.

Secondly, for China’s semiconductor manufacturing industry to catch up with companies like TSMC within 10 years would be a tall order. Gaps in know-how will be difficult to overcome in a short period of time, unless foreign companies help China shorten this learning curve.

China’s nationwide innovation campaign will undoubtedly result in failures and embarrassments, as has happened before. For example, the much-hyped Wuhan Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. earned some $15 billion in investment over three years before it was revealed as a hoax. Of the many new Chinese chip factories being built, it remains to be seen how many of them will become operational.

It is also conceivable that Beijing would carry out more intensive intelligence operations to acquire desirable data and technologies. The West, especially the U.S., will be alert to such an eventuality.

China will take years to reach the level of autonomy it seeks. The U.S. will also need time to meet the targets of the Biden administration. But the U.S. has more allies than China, as well as a solid foundation of basic research and a powerful culture of technological innovation. Still, the U.S. government cannot doze off, otherwise, its rivals could take the high ground.