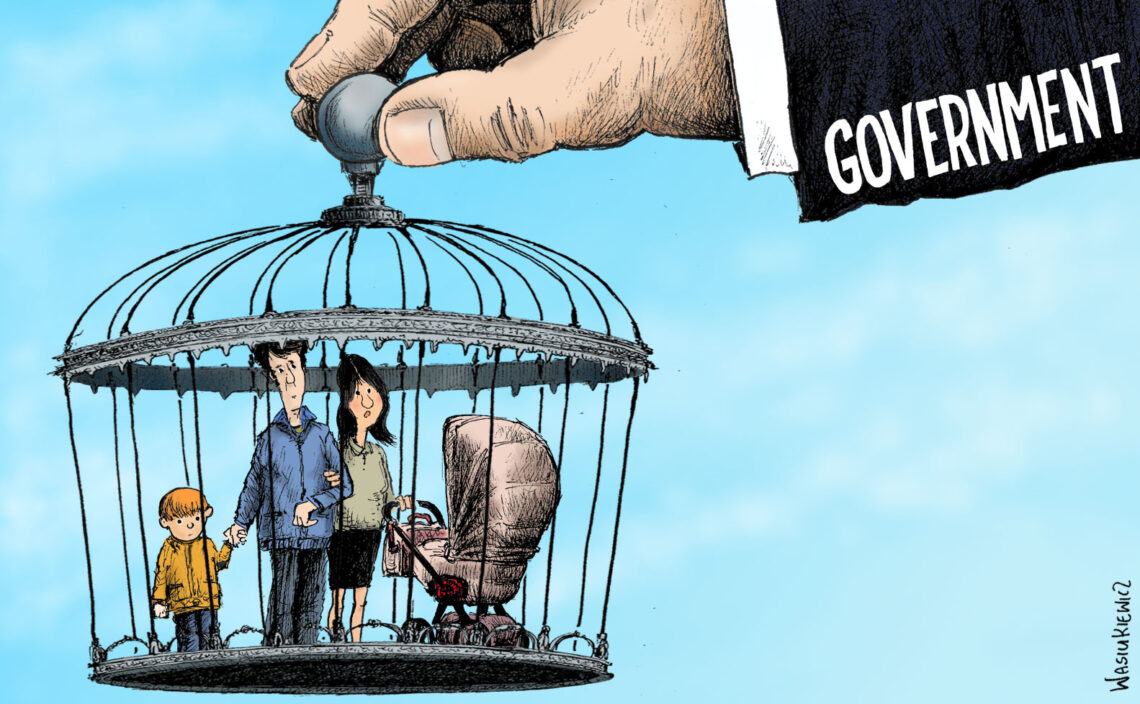

New pressures to curb individual rights

The Covid-19 pandemic has allowed governments to enact authoritarian emergency legislation, with no guarantee that the curtailed civil rights will later be returned to the population. China’s example shows what could await European countries.

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

In 1947, Albert Camus published his existential novel, The Plague. Set in the Algerian city of Oran, one of its central characters is a doctor who treats the first victim, quickly coming to see the scale of the threat. He warns the lethargic authorities that they must urgently act. In response, the civil authorities imposes martial law and curfews, and curtailed human rights – banning funeral rites – demoralizing the populace.

There are uncomfortable parallels with contemporary events. Oran was locked down and quarantined, stirring and unleashing baser instincts of exploitation, criminality, violence and looting.

Stranger than fiction

In 2020, the surreal, dystopian nature of the coronavirus pandemic is stranger than fiction. Thousands of people die each day, while civic buildings and conference centers are being repurposed as hospitals.

Distinguished scientists, epidemiologists and public health experts argue over the numbers of anticipated fatalities, the closing down of economies, the locking down of communities and the self-isolation of the vulnerable while we ask ourselves when will it end; what will the long-term implications be?

Camus’ novel poses some of the same serious questions – about what it means to be human, about the effects on the trajectory of our destiny and progress, and how quickly, under the cover of darkness, we will see the erosion of gains – democratic, social, communal and personal.

All too easily our freedoms and liberties can slip through our fingers.

As we try to focus on developing road maps out of lockdown and on the phenomenal economic and social challenges, they look daunting. How will we manage the consequences of fractured bonds in institutions like the European Union; the exposure of glaring and disfiguring inequality in society, especially in the United States; the urgent need to recalibrate our naive relationship with the hostile Chinese Communist Party (CCP)? With only limited public health support services available to them, how will developing nations respond to the looming COVID-19 catastrophe?

Emergency powers

In relighting “the lamps going out all over Europe” – a phrase used by Sir Edward Grey at the outset of World War I – we will be faced by the worst levels of unemployment, bankruptcy and economic decline since the Great Depression. We will also be faced with the age-old temptation to keep emergency legislation in place.

All too easily our freedoms and liberties can slip through our fingers. We must be insistent that powers seized by governments are quickly returned to parliaments and people. It too easily suits authorities to make permanent those powers taken “temporarily” at times of peril.

In 1911, against a background of espionage and the Agadir Crisis – a short-lived panic centered on the deployment of French soldiers in the interior of Morocco – and with the London Evening Standard stirring the populace with headlines about endless Balkan uprisings, the British Parliament passed the Official Secrets Act. Some of the Act’s legislation remains in force to this day.

Parliament enacted the legislation in less than 30 minutes. In a pell-mell rush, it created far-reaching offenses ostensibly relating to espionage. But Section 1 of the new law applied to anyone deemed to be working “for any purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State.” In 1962, the British Law Lords determined that Section 1 could also be applied to anyone involved in sabotage and other acts of physical interference. And it did not end there.

Giving the state the power to track your location is a clear breach of civil liberties.

During the Cold War, campaigners for freedom of information pointed out that if a parent wanted to find out how best, in the event of a nuclear war, to look after their children, they were prohibited from doing so because it was an official secret. Nor could they establish what poisonous gases were being emitted from the factory chimney opposite their home, because that too was an official secret. These down-the-rabbit-hole, Alice-in-Wonderland measures, were peacetime laws enacted in a climate of fear and panic.

Reformers also pointed out that these powers made it an offense for the queen’s gardeners (as employees of the Palace) to reveal the secrets of the queen’s compost heap or her herb garden; or, more seriously, the governance and workings of a whole raft of civil organizations and public bodies.

The coming of war, followed by grave economic and political uncertainty, gave the government the cover to take and to retain powers which, in normal times, would have otherwise been denied it, and those laws remained entrenched for decades.

Two world wars, which saw mass internment, vast movements of peoples, and domestic provisions like the removal of signposts to confuse an invading enemy, all existed in a world where national security demanded newspaper censorship and tight lips. Introduced in 1912, Defence and Security Media Advisory Notices – official requests to newspaper editors not to publish or broadcast items where national security might be compromised – are still in use in the UK.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, Cabinet Minister Herbert Morrison, who served as the Lord President of the Council, wrote that “We have learned much during the war, and there should be no return to the old timidity and reticence.” He urged the disavowal of restrictions on free speech which, in peacetime, could be used to undermine a free and democratic society. However, it proved far more difficult to eliminate government powers than for the government to take them. Until the rapidly enacted 2020 Emergency Powers Act – put through both houses of the British Parliament at breakneck speed – most of us were blissfully unaware of the sweeping powers in the obscure Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984. Together, these laws provide powers to cancel important national and regional elections and to suspend Parliament – actions normally associated with authoritarian states.

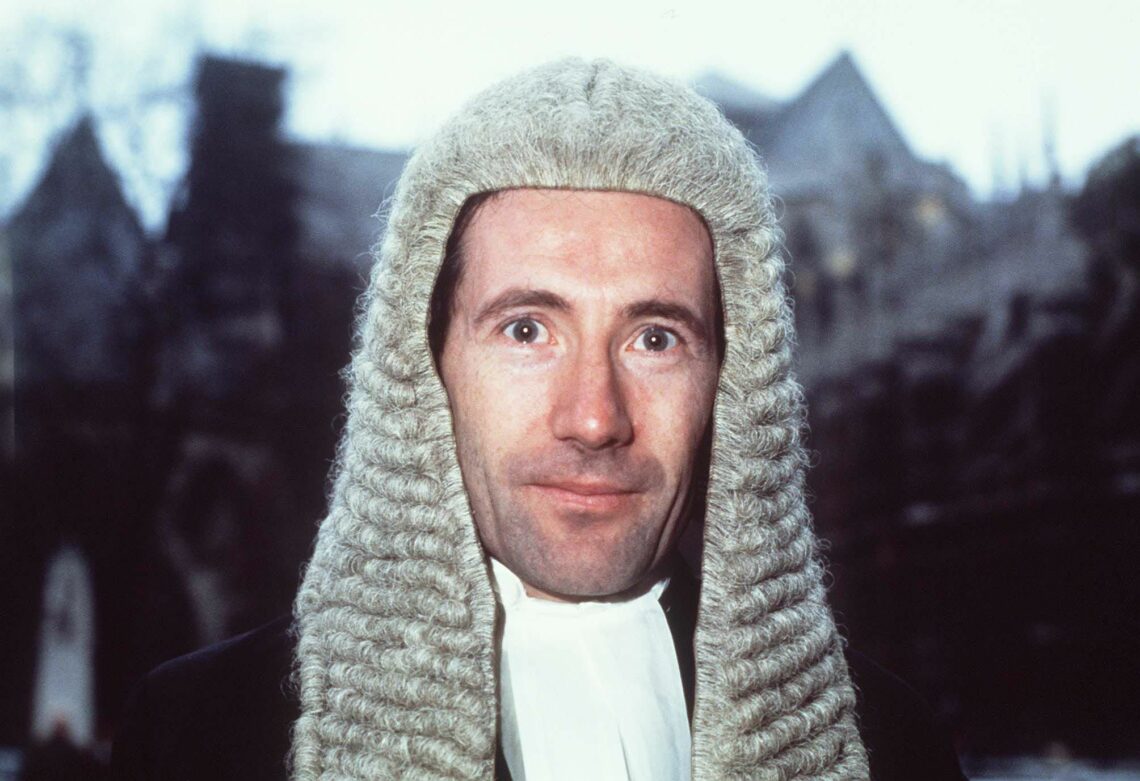

As Lord Jonathan Sumption, a recently retired Supreme Court Judge, has warned, the powers that the British government has taken are “frankly disgraceful.” Referring to the decision of the Derbyshire police “to shame people from using their undoubted right to travel to take exercise in the country and wrecking beauty spots so that people don’t want to go there,” he said, “This is what a police state is like.” While accepting that powers are needed to control the spread of the virus, he questioned whether we have the right to “put our population into house imprisonment.” Some might call this the power of mass arrest.

I doubt that this was the intention of Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who is recovering from his own battle with coronavirus. But when he gave the police new powers of arrest, fines and detention to be used for those breaking social distancing rules, it became clear how quickly a local police chief can take on the appearance of an overzealous Stasi operative.

In Scotland, under the cloak of trying to protect citizens from COVID-19, Nicola Sturgeon’s government tried to suspend jury trials for 18 months. Senior lawyers warned that once jury trials were ended, they would not be reinstated.

The right to a jury trial, established in 1215 in Article 39 of Magna Carta, is a cornerstone of the British legal system and should be jealously guarded. In 1798, Thomas Jefferson told Thomas Paine that “I consider trial by jury as the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.” In 2020, are we really willing to kick away this bedrock of our judicial system without serious consideration for the kind of society this would create?

The CCP’s concealment

Of course, this is not the Reich or Communist China. But the CCP sneers at our liberal democracies and tells us we must learn to be like them. To achieve that, it has a clear ideology and strategy – everything from controlling the World Health Organization and United Nations agencies to influencing and infiltrating national assets such as universities. China owns British Steel, large swathes of British industry and wants to control 5G networks and the UK’s nuclear energy.

China already owns 15 percent of the UK’s national debt, worth about 267 billion pounds (a move from the same playbook of debt dependency it is using to conquer and colonize Africa). And look at how the Chinese used coronavirus to demonstrate their power and control of their population. We have not yet introduced China’s Orwellian surveillance technology (although we helped develop it). However, coming our way soon will be the application that China requires citizens to have on their phones to be allowed to travel. The app is color coded to show your medical condition. Without the right code, citizens cannot use the subway or enter many buildings. Break the rule and the CCP will be sending their people to see you soon.

Giving the state the power to track your location and enabling such data to be used by other organizations is a clear breach of civil liberties and the right to privacy. Take it to its logical conclusion and violators will be sent to a reeducation center in Xinjiang. Ask the Uighurs, Falun Gong, or other religious and political dissenters.

It is the job of parliaments to insist that liberty and the rule of law do not become casualties of this epidemic.

In China, the coronavirus pandemic has produced heroes as well as villains. One of the greatest heroes was ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, who tried to warn the world of the impending disaster. He was forced to recant by the Chinese authorities and subsequently died of COVID-19, along with three other doctors at his hospital in Wuhan. The CCP’s concealment, silencing of opinion and dissent, and the repression of doctors trying to save lives is a far more deadly disease than coronavirus itself. This is a lethal system and ideology which has brought enormous suffering to the world and, at last, all over the world, from Left to Right, willful indifference and naivety about the CCP is giving way to a more hardheaded appreciation of the dangers it poses.

We should be listening to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protesters like distinguished lawyers Martin Lee QC and Margaret Ng, who were among the 15 pro-democracy leaders recently arrested under the cover of COVID-19. Instead of sleepwalking, we need to be far more alert to the danger of totalitarianism.

Authoritarians come in carpet slippers – now bearing face masks and ventilators – as well as in Type 99 Chinese battle tanks.

Liberties and freedoms

Yet many seem oblivious to the dangers, distracted and overwhelmed by the pandemic. One British newspaper poll suggested that 86 percent of British people would be willing to give up civil liberties to help beat coronavirus. But there is a difference between altruistically loaning the state powers that the people had wrested away over centuries through great sacrifice, and handing them back permanently. Such powers restrict liberties and freedoms bought with blood and toil since the promulgation of Magna Carta.

In The Plague, Albert Camus explored the effects of lockdown and martial law on a grieving and demoralized population. That was fiction. Today, we can see the first signs of despondence, mental illness and noncompliance. We see families holed up in tenement blocks, without gardens, trying to cope with the confinement of toddlers and young children. We see isolated elderly people, deprived of human contact without the tools of social media. They need practical help, not the threat of fines and jail; not the loss of precious human rights and liberties.

Good governments may well be motivated to take bad powers in the public interest. The danger for the future will be bad governments keeping what they see as useful powers to exert ever greater control of their own people.

It is the job of parliaments – currently missing in action – to insist that liberty and the rule of law do not become casualties of this epidemic: lost under the cloak of darkness.