The decline of the American labor union

Union membership in the U.S. is at the lowest rate in history, owing to forces including globalization, technology and the rise of the service sector.

In a nutshell

- Offshoring and technology have eroded manufacturing unions

- The partisan politics around unions have evolved

- Union activism is unlikely to rebound

Protests involving millions of workers have erupted across Europe in recent months, including mass pickets in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Spain. This continental labor upheaval stands in stark contrast to the decline of American unionism over the past several decades.

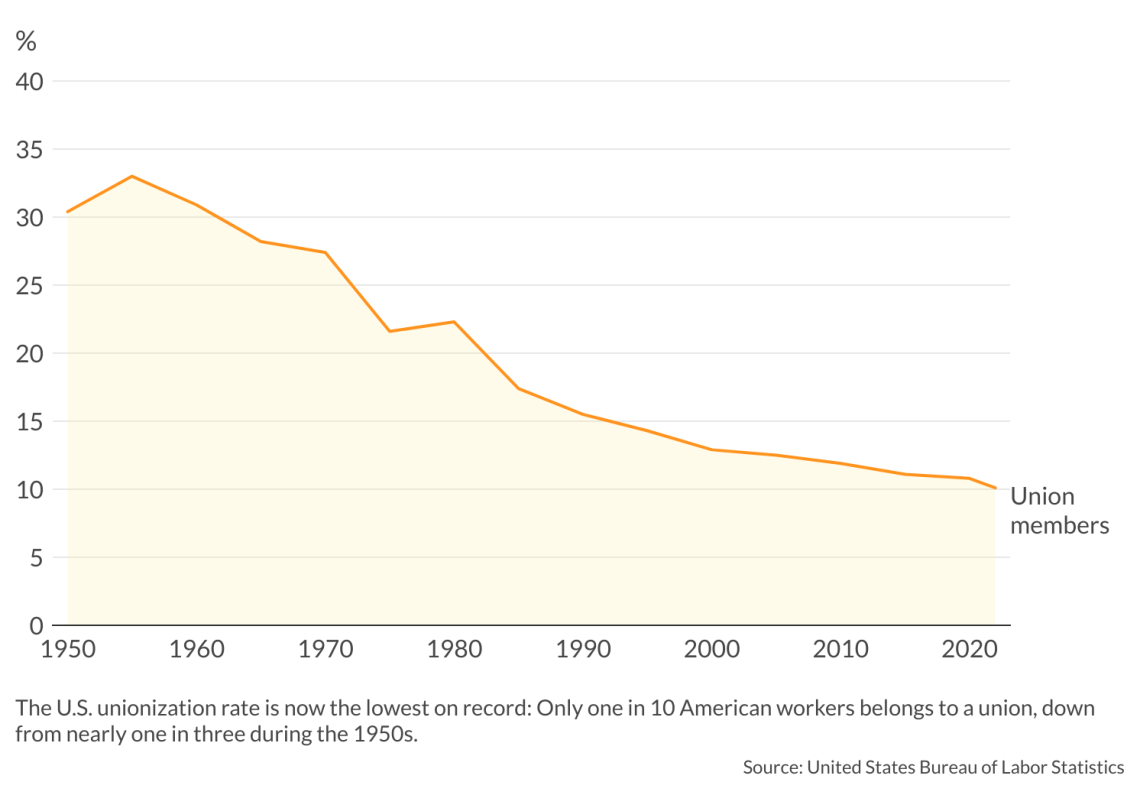

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics recently reported that the nation’s unionization rate – the proportion of employed workers who are union members – is now the lowest on record, at 10 percent. Only one in 10 American workers is a union member, down from nearly one in three workers during the 1950s.

The decline has occurred across industries as well as states, leaving the U.S. with one of the lowest union densities among major industrialized economies, according to the Hamilton Project. This is a striking development for a once-formidable force in American politics and the economy.

Private sector and public sector

The decline in union membership is only one aspect of the significant transformation of organized labor in the U.S. There has also been a major shift in the occupational share of union membership. Organized labor today is dominated by public-sector employees, whose membership rate of 33.1 percent is more than five times higher than the 6 percent rate of private-sector employees.

Public-sector unions were virtually unheard of in the U.S. until the mid-1950s, when private-sector unions began to decline and local, state and federal governments expanded massively. Union membership rates currently are highest among police officers and firefighters (34.6 percent) and teachers (33.7 percent). They are lowest in sales (3.0 percent), computer and mathematical occupations (3.3 percent), and food preparation/serving (3.6 percent) – all jobs related to the dominant service economy and tech sector.

Read more reports by Diane Katz

The backlash builds against ESG investing

The decline in private-sector unionism has enabled the adoption of “right-to-work” statutes (which end compulsory union membership) in onetime strongholds of organized labor, such as the states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana. In fact, 30 percent of the country’s 14.3 million union members now reside in just two heavily Democratic states: 2.6 million in California and 1.7 million in New York, two states that account for only 17 percent of wage and salary employment nationwide.

Change drivers

Globalization and technology have contributed significantly to the decline of private-sector unionism in the U.S. While domestic manufacturing drove union membership in the mid-20th century, the U.S. now has far fewer manufacturing jobs than in decades past, both in absolute numbers and as a proportion of overall employment. The decades-long slide began in the late 1940s when manufacturing accounted for 32 percent of American jobs, compared to 8.5 percent today.

The steepest decline has occurred in the past two decades, as foreign competition and offshoring contributed to a reduction in U.S. manufacturing jobs of an astounding 26 percent – from 17.2 million in 2000 to 12.7 million today. More intense competition has also driven manufacturers to cut costs by shifting from Midwestern “Rust Belt” states to Southern states that lack a strong legacy of (more costly) organized labor.

To be sure, European economies have also been affected by globalization and technology, but the “pattern bargaining” that strengthens union advantages still dominates the continent. This is not the case in the U.S., where pattern bargaining virtually no longer exists. Leveraging contract terms across entire industries effectively collapsed during America’s double-dip recession of the early 1980s, with the government bailout of Chrysler Corp. and subsequent union concessions by the United Auto Workers at Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Corp.

Facts & figures

In addition, the rise of the service sector distinctly disadvantages union organizing efforts. According to Columbia University Professor Suresh Naidu, service workplaces are relatively small, which increases the transaction costs (and lowers the return) of organizing. Moreover, higher turnover in service jobs weakens the worker solidarity that otherwise drives union allegiance. These factors are particularly evident in the largely unsuccessful attempts to unionize companies like Starbucks. The growth of the “gig economy” has also frustrated union organizing efforts for businesses such as Uber and Lyft, as their workers are considered independent contractors and exempt from union protections.

Lastly, labor’s political activism in past decades led to extensive worker protections in statute, including health and safety standards, unemployment compensation and retirement benefits, and constraints on employers faced with union drives. Although these developments have produced benefits, such governmental involvement has (to some degree) supplanted unions as the defender of labor. In other words, there is simply less need for unions when the government so heavily regulates the shop floor.

Blue-collar politics

Organized labor remains a potent force in the political arena, perhaps even more so than its historic role in economic affairs. But unions in recent decades have not been politically homogenous, and Republicans currently benefit from a significant increase in support among blue-collar workers. The reasons are not difficult to discern: for many workers, the economic focus of the Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump administrations held greater appeal than left-wing, social elements of the Democratic Party agenda.

As an article in the leftist, pro-labor journal Jacobin put it during the heated 2016 presidential contest: “Democratic Party liberals have become even more furious and dismissive of working-class whites. … The party has established a clear line on white wage-earners: they’re all either dying (demographically or literally), irrelevant in an increasingly nonwhite country, or so hopelessly racist they can go off themselves with a Miller High Life-prescription-painkiller cocktail for all they care.”

While domestic manufacturing drove union membership in the mid-20th century, the U.S. now has far fewer manufacturing jobs than in decades past.

As a candidate in the 2020 race, Joe Biden sought to win back workers for the Democratic Party by vowing to be “the most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in American history.” Executive branch agencies under President Biden have certainly delivered in regulatory matters, but his high tax-and-spend policies, which have fueled record inflation, have proven disastrous for wage earners.

The costs of public-sector unions have also weakened taxpayer support for organized labor. For example, researchers Sarah F. Anzia and Terry M. Moe have documented that cities with unionized police and firefighters will pay 15 percent to 25 percent more than cities without collective bargaining.

Scenarios

A confluence of factors has contributed to a dramatic decline in union membership since the 1950s, and there is little reason to believe that a major rebound will occur. There is simply nowhere to go – no amount of union victories at Starbucks outlets can match the labor might of the bygone era of iron and steel. And, unlike union activism in Europe, organized labor in the U.S. has always been in some tension with the nation’s founding principles of individual liberty (over collectivism) and capitalism (over socialism).

With Republican control of the U.S. House of Representatives, there is virtually no chance that organized labor will secure even greater statutory advantages in organizing and contract negotiations, such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act. Nonetheless, the Biden Administration will continue to bolster unionism through administrative fiat and regulatory adjudication.

Union drives will become increasingly costly as they are fought in a scattershot manner, targeting individual Starbucks locations, Apple stores and Amazon outlets. Legal challenges will persist over the status of gig workers, with cases focusing on whether gig workers are independent contractors or actual employees eligible for statutory protections.