What next for divided Spain?

Spain’s government is in a fragile spot as its tax-and-spend policies dig it deeper into debt, while the population becomes more ideologically polarized.

In a nutshell

- Trends that started in 2009 have polarized Spanish politics

- The government’s economic policy is exacerbating the difficulties

- The right is on the rise, and could win the next election

In Spain, the leftist coalition led by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez is halfway through its mandate. The moment is marked by political polarization and a volatile economy, all while the European Union is facing a crossroads.

The Spanish political scene has been highly divided for about a decade. The country’s transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, which started in the mid-1970s, caused deep societal rifts. Most Spaniards thought those divides had been bridged, or at least patched over, but the 2008 financial crisis reopened them with a vengeance.

Three key events helped shape Spain’s current state of polarization: the founding of the ultra-right Vox party in 2013, the creation of the left-wing populist Podemos party in 2014 and the 2017 independence referendum in Catalonia. The emergence of parties on the extremes of the political spectrum – both with charismatic leaders – along with the rising tension between sovereignty and self-determination, created a political environment where the opportunities for compromise seem exhausted.

Spain never fully recovered from the 2008 global financial crisis.

The system in which two large, more centrist parties dominated the country’s politics has collapsed, and political instability is the norm. In 2019, after two elections and months of trying to form a government, Mr. Sanchez – the leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) – teamed up with the Unidas Podemos (United We Can) alliance, a coalition of far-left parties, to form a government. The governing coalition also depends on regional nationalist parties like Basque Country Unite (EH Bildu) and the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC).

Unidas Podemos presents itself as a force against neoliberalism and gained popularity on the back of the angst and disillusion caused by the financial crisis. Vox, on the other hand, became a key political actor due to anger over the Catalan separatist movement. Still, Vox has made headway on economic issues as well, gaining ground in former socialist strongholds, like the working-class neighborhoods of Madrid.

Spain never fully recovered from the 2008 global financial crisis, which took a huge toll on the youth and the middle class. Now, as the country confronts another crisis brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, the fragility of the government coalition is becoming clearer.

Economic distress

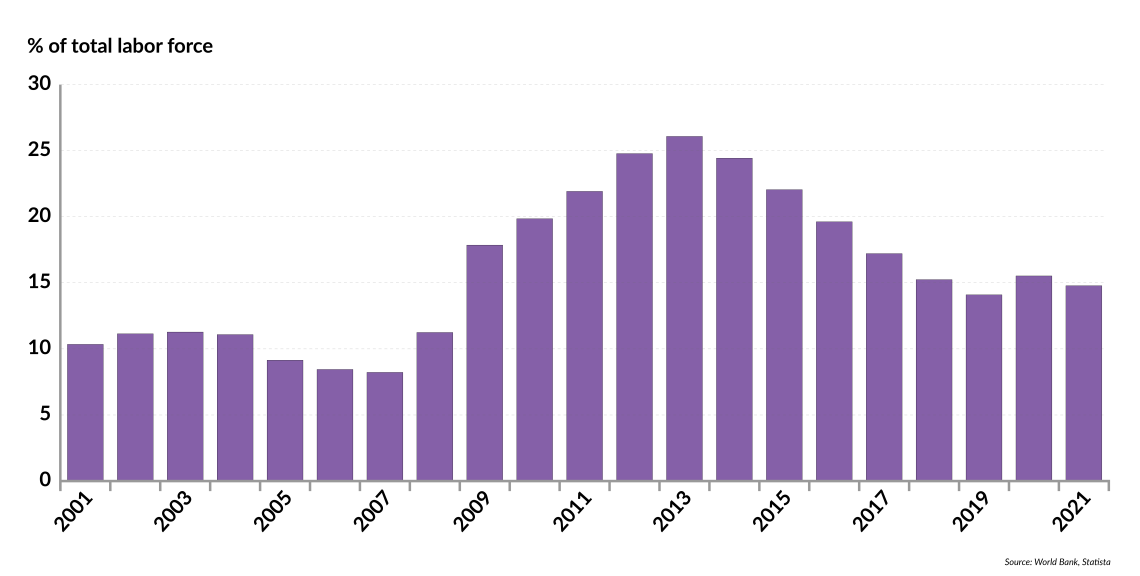

Over the first several years of the 21st century, the Spanish economy saw healthy growth and was one of the top performers in Europe. But Spain’s extended honeymoon of economic expansion and political stability ended abruptly in 2008. As financial markets crashed, the country’s structural problems, like low levels of savings, productivity and competitiveness, compounded the distress. Spain’s gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 9 percent between 2008 and 2013, while unemployment rocketed to 26 percent – 55 percent among young people.

When Mariano Rajoy, leader of the center-right People’s Party, became prime minister in 2011, he began carrying out a plan of fiscal discipline and austerity. By 2015, the recovery was gathering momentum and Spain again had become one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe, even despite persistently high unemployment rates.

Facts & figures

Spain’s unemployment rate, 2001-2021

It may have been too little, too late. The political shifts that would polarize the country were already well underway. The left’s demonization of fiscal discipline seemed irreversible. Covid-19 began spreading, and the government imposed a severe lockdown. Now, Spain is lagging on the road to recovery.

Several factors have caused Spain’s economic difficulties. The hospitality sector, ravaged by the pandemic, plays an outsize role in the country’s economy. Energy prices have risen to record highs, private consumption has slowed, and the auto industry has been hamstrung by supply-chain blockages. Inflation, weak economic growth and high unemployment – reaching 16.26 percent in 2020 – have battered the population.

Support for solutions to these challenges falls along increasingly divided political lines. The leftist coalition argues that recovery depends on public expenditure, while those on the right call for lower taxes and smaller government.

Socialist-capitalist tension

Prime Minister Sanchez secured an important political victory when parliament approved a labor reform required for Spain to receive 12 billion euros of EU pandemic recovery funding. The bill passed by a single vote and overturns several pro-business measures introduced by the government of Prime Minister Rajoy in 2012.

While controversial, the 2012 reform helped raise competitiveness, increase fuel exports and create jobs. The new legislation introduces a level of rigidity that could hurt the already volatile labor market, pushing more workers into the informal sector. The government has also passed a “right to housing” law, which paves the way for rent controls across the country.

Responsible for Spain’s highest-spending budget in history, the Sanchez administration is also preparing a tax reform to increase government revenue. One of its most controversial aspects is fiscal harmonization, which would reduce local autonomy and the economic dynamism that competition between regions brings.

Many worry that EU funds will simply pay for the government’s ever-increasing expenditure, with no benefit to the private sector.

Even before the draft law was presented, the reform had already ignited political controversy. Tax competition has benefited some regions to the detriment of others. Madrid, which leads the country’s regional fiscal competitiveness index, attracted significant investment in 2020 and 2021. Many companies are voting with their feet, moving from Catalonia – which comes last in the index – to Madrid.

The president of the Madrid region, Isabel Diaz Ayuso, was reelected last year in what was seen as a resounding victory against the left. During the campaign, she defended the end of lockdowns and lower taxes, and took a rather polarizing stance under the slogan “socialism or freedom.” With the support of the ultra-right Vox, President Ayuso has just approved preliminary legislation aimed at blocking harmonization.

The 140 billion euros in grants and loans that Spain is expected to receive under the EU recovery and resilience plan has also become a political football. While few warn of the consequences of accepting such largesse, the People’s Party and Vox have raised doubts about its management and distribution. Many worry that instead of financing strategic, growth-inducing investment, the funds will simply pay for the government’s ever-increasing expenditure, with no benefit to the private sector.

European funds

The lifting of spending and debt restrictions in 2020 was a lifeline for the Spanish economy. It also received support from the European Central Bank amounting to some 40 percent of its GDP – one of the largest shares in Europe. These factors make Spain extremely vulnerable to policy changes at the ECB. The bank’s plan to slowly withdraw stimulus is already causing worries in Madrid, and Prime Minister Sanchez has been warned by his German counterpart that a return to fiscal discipline will be necessary.

However, it remains unclear what path Europe and the ECB will take. Prime Minister Sanchez can count on allies like French President Emmanuel Macron and Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi in his opposition to the return of responsible monetary policy and fiscal prudence. Mr. Macron is seeking reelection this year and fierce competition on the right has forced him to go after votes on the left. He has therefore called for making the EU’s budget rules more flexible, suggesting that fiscal discipline is “obsolete.” Prime Minister Draghi is supporting the initiative – a change from his previous position. Their calls are based on the narrative that the post-Covid era represents a unique opportunity to introduce far-reaching changes.

Scenarios

The ideological shift toward polarization is by no means exclusive to Spain. Among countries in Europe, the divide also falls along lines between those who want to transfer more sovereignty to the EU and those who want a Europe of nations that is united but preserves its diversity. Spain’s economic outlook, in the short to medium term, also hinges on decisions that are outside of Madrid’s control. In light of all this, we should consider three scenarios.

Under a first and most likely scenario, the leftist coalition will remain in place until the end of its term in 2023. Until then, however, Spain will see further polarization and instability, as evidenced by the government’s weak support in parliament and its efforts to accommodate the demands of its partners on the left. This scenario would have consequences beyond 2023. Regardless of the electoral results, stability and consensus will remain elusive. Implementing meaningful reforms will be difficult.

The degree of instability and popular discontent will heavily (though not entirely) depend on economic factors and, on that front, the most likely scenario is far from ideal. Despite rising private consumption and a strong recovery in the tourism sector, inflation and debt are expected to continue to hold back growth, while the government’s policies – including more taxation – could compromise competitiveness. Under this scenario, debt would become a major concern as the ECB raises interest rates. This would add to tension within the Unidas Podemos coalition, especially between PSOE and Podemos.

The most likely political consequence would be a victory of the right in the 2023 elections. The right, however, is at a critical juncture. The People’s Party is engulfed in a tussle between its leader Pablo Casado and Ms. Ayuso. It remains unclear who will be in charge in 2023. The main difference between the two, in strategic terms, is that Ms. Ayuso would be willing to govern with the support of Vox (which recently surpassed the People’s Party in the polls), while Mr. Casado would not.

The Ayuso strategy – polarizing the discourse without resorting to radical policies – allowed her to contain the growth of Vox without alienating its supporters and helped the People’s Party gain a resounding victory in the regional elections.

Then there are two alternative scenarios that, although less likely, must be considered. One is that early elections could be held. Economic challenges and rising popular discontent could force the coalition parties to reposition themselves to preserve support among their constituencies, leading to a dissolution of the current government (triggered, for example, by a rejection of the 2023 budget).

The final potential scenario is characterized by a rapid economic recovery, boosted by the end of the pandemic and a return to normalcy in global supply chains, along with energy prices stabilizing and the EU allowing countries to maintain budgetary and fiscal flexibility. While this would not strengthen the Spanish economy, it could delay the adverse effects of the current policies – and their political consequences.