In postelection DRC, transition looks like restoration

After delaying elections for two years, former DRC President Joseph Kabila appears to have arranged for a stand-in, nominally from the opposition, to win the presidency in a manipulated ballot. The international community seems to be turning a blind eye because it prefers stability to the prospect of turmoil and civil war.

In a nutshell

- Leaked data show opposition candidate Martin Fayulu won the DRC presidential ballot

- The official victor, Felix Tshisekedi, cut a power-sharing deal with long-time incumbent Joseph Kabila

- This maneuver won support from the international community as the price of stability

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly Zaire, has had a turbulent political history. Plagued by instability, authoritarianism and violence, it has been prone to military coups and civil wars since declaring its independence from Belgium in 1960.

President Mobutu Sese Seko (1965-1997) ruled the country as a military dictator for more than three decades and managed to preserve some level of unity among its disparate ethnicities and regions. But tribalism and the lack of strong, unified national institutions – and especially the armed forces – remain a key vulnerability for the DRC. This allows an opening for its neighbors, notably Rwanda and Angola, to meddle in the country’s domestic affairs.

Both countries played decisive roles in the crisis that followed Mobutu’s ouster in 1997, helping engineer the victory of President Laurent-Desire Kabila (1997-2001), who was endorsed by the Angolans. Laurent Kabila ended up being assassinated by one of his bodyguards, and he was succeeded a few days later by his 29-year-old son, Joseph.

Joseph Kabila managed to remain in power for the next 16 years. But constitutional term limits barred him from running for a new mandate, which should theoretically have forced him to step down. Instead, he postponed the 2016 presidential elections for more than two years, refusing to honor a transition agreement with the opposition and clinging to office amid heavy repression, chaos and violence. Not until early last year did he concede and set a date for new elections. The Congolese finally went to the polls on December 30, 2018.

Split opposition

On January 10, 2019, the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), which had been instrumental in helping Mr. Kabila delay the elections, ostensibly for logistical and technical reasons, declared a surprise winner: Felix Tshisekedi. The way he achieved that result is instructive.

Three broad coalitions contested the presidential campaign and the simultaneous elections to the 500-seat National Assembly. Mr. Kabila’s ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) was represented by Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister Emmanuel Shadary, who ran as an independent leading the Common Front for Congo (FCC).

The opposition split, despite previous vows to present a common front against the Kabila regime.

Despite previous vows to present a common front against the Kabila regime, the opposition was split into two groups. The bulk was in the so-called Lamuku Alliance, backing presidential candidate Martin Fayulu, a businessman and longtime ExxonMobil executive. Mr. Fayulu was a relative newcomer to politics but enjoyed the support of opposition heavyweights Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moise Katumbi, who had been disqualified from running by CENI in a politically motivated ruling. Mr. Katumbi, in particular, had been considered the most formidable opposition candidate before CENI’s decision.

The second opposition grouping was the Coalition for Change (CACH), formed by an alliance between Mr. Tshisekedi’s Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDSP) and Vital Kamerhe’s Union for the Congolese Nation (UNC). Mr. Tshisekedi is opposition royalty, being the son of veteran Congolese politician Etienne Tshisekedi, who ran against and claimed to beat Mr. Kabila in the disputed 2011 election and led the anti-Kabila opposition until his death in February 2017.

Originally, Mr. Tshisekedi and Mr. Kamerhe, the former president of the National Assembly, had agreed to be part of the united Lamuku Alliance behind the relatively obscure Mr. Fayulu. But less than 12 hours after signing the coalition agreement in November 2018, they withdrew, citing pressure from their supporters. This decision wrecked the opposition’s broad-front strategy and gave Mr. Kabila strong leverage, as would become clear two months later.

Trouble counting

According to the official returns published on January 10, Mr. Tshisekedi won a slim victory with 38.6 percent of the popular vote, against 34.8 percent for Mr. Fayulu and 23.8 percent for Mr. Shadary. The remaining votes were split among more than a dozen minor candidates.

However, according to opposition and civil society institutions, including the Catholic Church (which fielded 40,000 poll watchers), the actual results were a landslide victory for Mr. Fayulu, who received about 60 percent of the vote. These figures were corroborated by preliminary data compiled by CENI and leaked to the media before the official results were announced, showing Mr. Tshisekedi and Mr. Shadary each getting less than 20 percent of the vote.

Facts & figures

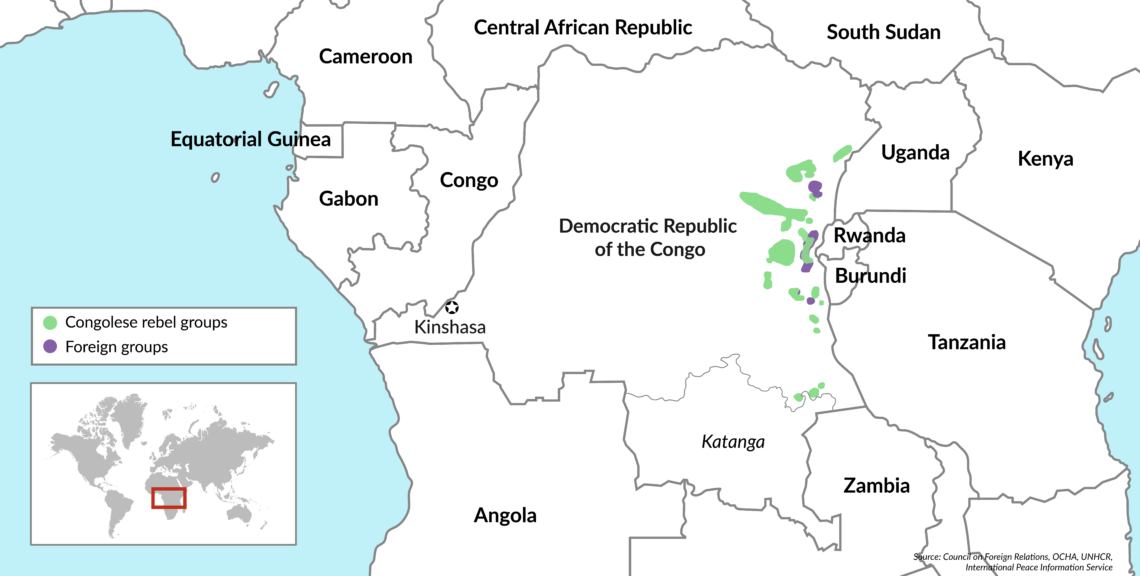

Armed groups in the DRC

Mr. Fayulu, who had consistently led in the polls and was considered by analysts an almost certain winner, denounced the results and demanded a recount. He applied to the Constitutional Court to annul the official returns, which he called an “electoral putsch.” The court, generally perceived as beholden to Joseph Kabila, rejected Mr. Fayulu’s appeals and upheld the election of Mr. Tshisekedi, who was duly sworn in on January 24.

Tension and a sense of insecurity gripped the country. On January 12, a meeting of Fayulu supporters in Kinshasa was dispersed by security forces. There were similar incidents in other cities, and fears of unrest soon spread.

Strange events

Given President Kabila’s authoritarian past and strong resolve to stay in power, the shocking election results immediately aroused suspicions among local observers and foreign experts. CENI had consistently sided with the former president’s efforts to delay the campaign, which included strange events such as a suspicious fire that destroyed 7,000 of the 10,000 voting machines that were supposed to be used in Kinshasa.

The Catholic Church, which had the largest vote monitoring operation, expressed early skepticism about the transparency and fairness of the results. These concerns were echoed by the international community, especially France and the European Union. The African Union was also initially critical, even calling for a recount, but quickly decided to accept the outcome.

The United States struck a similarly ambivalent stance. On the one hand, it sanctioned five Congolese officials deemed to have been involved in “significant corruption relating to the electoral process” – including the heads of the electoral commission, the Constitutional Court and the National Assembly. At the same time, however, the State Department praised the “historic” peaceful transfer of power and said its actions were not directed at the new DRC government.

Balance of power

All signs pointed to a backstage deal between former President Kabila and Mr. Tshisekedi. Despite his family pedigree, Mr. Tshisekedi had been regarded as a political amateur by many in the opposition, which was perhaps one reason he was passed over by the Lamuku Alliance as a presidential candidate in favor of the almost equally inexperienced Mr. Fayulu. Yet the abrupt pullout from the unitary coalition by Mr. Tshisekedi and Mr. Kamerhe in November 2018 bore many of the hallmarks of a pre-planned maneuver.

The pro-Kabila candidate’s poor showing may have been intended to lend credibility to the official results.

Another clever touch was the third-place finish of the official pro-Kabila candidate, Emmanuel Shadary. He had not been expected to do well, even though he was handpicked by Mr. Kabila. As minister of the interior and security, he had acquired a reputation for brutality and had been blacklisted by the EU for his role in violently suppressing opposition to the Kabila regime.

In all likelihood, Mr. Shadary’s poor showing was intended to lend credibility to the official results. Most of the vote-rigging in the presidential race, if observers’ claims are correct, went in Mr. Tshisekedi’s favor as part of an informal pact with Mr. Kabila to maintain the status quo. As we shall see, this alliance was confirmed publicly after the election.

An indication of Mr. Kabila’s plans for the real balance of power is given by the official voting results for the National Assembly, where the pro-Kabila FCC won in a landslide, gaining 337 out of 500 seats, compared with 94 for the Lamuka coalition and only 46 for Mr. Tshisekedi’s Coalition for Change. The proportions were similar in provincial elections, where Mr. Kabila’s coalition won 16 of 24 governorships in the first round, and Mr. Tshisekedi’s only one.

Diplomatic mission

Given the controversy over Mr. Tshisekedi’s victory, international recognition of the DRC’s new political leadership was crucial. Even though the initial reaction from Western powers and the African Union was critical, they acknowledged the first peaceful transfer of power in the DRC’s history.

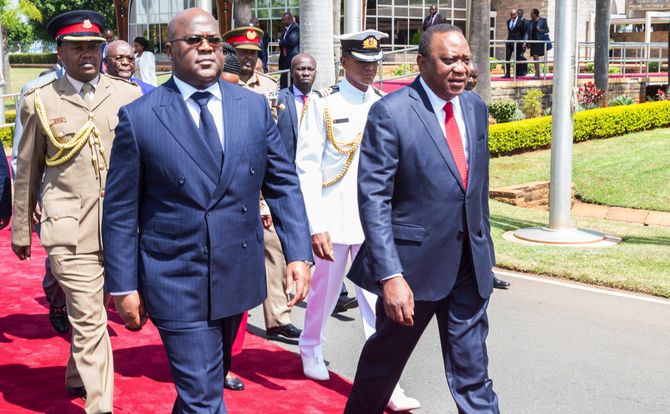

Immediately following his inauguration, President Tshisekedi embarked on a diplomatic charm offensive directed at his influential neighbors. In Angola, he met President Joao Lourenco, who gave his political blessing, followed by a quick trip to Brazzaville to win another endorsement from Congo President Denis Sassou Nguesso. Proceeding east, Mr. Tshisekedi went to Kenya for talks with President Uhuru Kenyatta. Last but not least, he was received by the powerful leader of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, a key political player who had initially expressed reservations about the transparency and fairness of the DRC’s elections.

In addition, President Tshisekedi took advantage of meetings organized by the African Union and the United Nations to confer with other regional leaders, including Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi of Egypt; Alassane Ouattara from Ivory Coast; Teodoro Obiang from Equatorial Guinea; Alpha Conde of Guinea; Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, and French President Emmanuel Macron. Mr. Tshisekedi also journeyed to Windhoek, Namibia, to solicit support from the South African Development Community (SADC).

This diplomatic push was bolstered by a visit from John Peter Pham, the U.S. special envoy for the Great Lakes Region. The meeting in Kinshasa could signal a rapprochement with Washington and a possible softening of the American position at the UN Security Council, where it was alone in demanding sanctions against officials responsible for the DRC election.

In mid-March, another visit to Kinshasa was paid by Tibor Nagy, the U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs, who held talks with the new president and representatives of other political parties. Mr. Nagy even issued a statement acknowledging Mr. Tshisekedi’s efforts “to increase transparency, promote accountability, combat corruption, reduce impunity and improve respect for human rights.” This cleared the way for President Tshisekedi’s official visit to the U.S. in early April, where his “change agenda” was endorsed by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

Internal arrangements

Domestically, the game was still on. Martin Fayulu, officially the defeated candidate, continues to maintain that he is the president-elect and to call on his millions of supporters to resist in a peaceful campaign of civil disobedience. Given the country’s sad legacy of internal conflict, however, there is always a risk that nonviolent protest could slide into armed resistance and civil war.

Early on, there had been speculation that Mr. Tshisekedi could offer Mr. Fayulu a compromise – perhaps some sort of power-sharing arrangement in exchange for his acceptance of the election results, allowing an easing of tensions and a new political normality. However, it soon became clear that this was not to be; the new president was focused on a different negotiating partner.

More than three months following Mr. Tshisekedi’s inauguration, no new cabinet lineup had been announced.

According to local sources, President Tshisekedi and former President Kabila met on February 17 to discuss the shape of a future coalition government. A few days later, Mr. Kabila conferred with his FCC coalition on parliamentary and cabinet cooperation with Mr. Tshisekedi’s CACH.

For more than three months following Mr. Tshisekedi’s inauguration, no new cabinet lineup was announced, as the new president worked with an informal team appointed by Joseph Kabila. Lists of possible ministerial appointments were leaked to the press, some of them even naming Joseph Kabila as the future prime minister. What became clear is that the government would be composed of FCC and CACH figures, with Mr. Fayulu and his Lamuku coalition decisively out of the game.

Kabila in charge

Any speculation about the new order was cut short on March 7, when President Tshisekedi announced a formal agreement between the CACH and the FCC, the latter now under the leadership of Joseph Kabila. The agreement specified that the two sides intended to govern together and that the FCC (meaning Mr. Kabila) would have a say in choosing the next prime minister.

Having already won two-thirds of the parliamentary seats and regional governorships, the pro-Kabila forces further tightened their grip in mid-March, when they gained a similar majority of the 109-seat Senate, which is elected indirectly through the provincial assemblies. As a former president, Mr. Kabila was automatically granted a Senate seat, giving him a convenient position from which to supervise the new cabinet.

With Mr. Kabila in firm control of the DRC’s parliament, Senate, and provincial governments, along with a likely majority of the cabinet posts and the premiership, it is clear that President Tshisekedi will have tremendous difficulties implementing political change on his own. Apart from spectacular gestures such as his release of 700 political prisoners, Mr. Tshisekedi may find his political role reduced to a purely ceremonial one.

Former President Kabila, on the other hand, appears to have found an ingenious solution to his “third-term” problem – somewhat reminiscent of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s stratagem of switching jobs with Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev once he reached the constitutional term limits. Most importantly, the new arrangements allow Mr. Kabila to maintain and protect the network of influence he built up over 18 years in charge of the country. Given his relatively young age (49 years) and deep-rooted interests in the lucrative mining industry, Mr. Kabila shows every indication of planning to stick around for the long haul.

Stability first

Even countries critical of the December elections were generally pleased with the political outcome, which was a mostly peaceful transfer of power. But this apparent victory for stability in the DRC and the region is not without risks in the medium term.

For many, the crucial point was to begin a gradual transition from Mr. Kabila’s corrupt, authoritarian regime. But as the past few months have shown, there is no convincing evidence that such a transition is taking place. The former president still retains his firm grip over the levers of power. As someone who will help determine the choice of prime minister (or take the post himself), Mr. Kabila will keep control of the key ministries and the security apparatus. Most of the military establishment also remains loyal to him.

Frustrated at failing to effect change through the ballot box, the Congolese might resort to more dangerous methods.

Secondly, Mr. Tshisekedi’s ascent to the presidency may have averted popular unrest in the short term, but it has done little to address the government’s fundamental lack of legitimacy. Without a genuine popular mandate, it will be even more difficult to implement the sweeping reforms so desperately needed by the DRC.

Finally, the December elections were supposed to be the country’s first democratic transfer of power in 59 years of independence. People voted for a change that they already see as illusory. Frustrated at their failure to effect change through the ballot box, the Congolese people might resort to other and more dangerous methods. Voices have already been raised in the country’s mineral-rich eastern regions – the traditional site of insurgencies – for more drastic measures, through arms if necessary.

So far, instances of violence have been scattered and sporadic since the election, with reports of dozens killed and perhaps several hundred injured, along with an estimated 240 “arbitrary arrests.” Yet dozens of armed groups remain active in the eastern provinces and could dramatically worsen the security situation in the Great Lakes region.

In short, the risk of civil war in the DRC has been mitigated but not eliminated, especially in the long term. The Congolese political landscape remains fragmented, which complicates the sustainability of the new political arrangements.

On the other hand, none of the DRC’s foreign partners or closest neighbors is interested in another civil war. With many other sub-Saharan countries in the throes of internal crises – Burundi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe come to mind – the major international players will probably do their best to prevent any outbreak.