Educational meritocracy and East Asia’s development miracle

Only a few countries leaped developing to advanced industrial nations in the 20th century. Among the fortunate five, four are from East Asia. Their policies have varied widely over the decades, but at least one common denominator stands out: a early selection process in the education system based on academic achievement.

In a nutshell

- East Asia’s economic success is not explained by politics and development strategies

- At the core of their superior performance are rigorously selective educational systems

- Dilution of this approach through political favoritism could threaten the “tiger” model

In the 20th century, very few countries made the leap from the ranks of developing nations to join the highly developed industrial nations. There are several recognized gauges of such progress: the World Bank list of high-income countries (which sets the cutoff at $12,056 of gross national income per capita), the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index (27 countries with a score of 5.00 or better), the United Nations Development Program’s (UNIDO) Competitive Industrial Performance Index (countries with scores of 0.12 or higher).

These indexes are very approximate tools for assessing development, but they also reflect an effort by reputable global organizations to rigorously compare countries by income, economic potential, social development and industrial might. As such, they represent solid analytical material.

Elite group

At the very top of the lists, one finds the “usual suspects” – much of Western Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia. However, there are also five relative newcomers: Japan (the first non-Western country to catch up with the leading industrial nations), Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan (China) and Israel.

Many other countries are present on some indexes and not on others. For instance, European countries like Italy and Spain make the World Bank and UNIDO lists, but fall short of the WEF’s “best” rating on the Global Competitiveness Index. Several Arab countries also rate highly on the World Bank and UNIDO indexes by income and social development, but score much worse on industrial performance and competitiveness. The failure of most Southeast Asian nations, once called “tiger economies,” to exit the middle-income trap is made obvious by their scarcity at the top tiers of these rankings. Of the Latin American entrants, Chile, Uruguay and Argentine figure in some indexes. African countries are completely absent.

It does seem possible to identify one factor common to all four East Asian economies in this select group.

Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Israel make the cut in every case, so one can conclude with a high degree of confidence that they have joined the club of highly-developed industrial countries.

Why did these countries succeed in catching up while the rest of the developing world failed? With the whole field of developmental studies hard at work to answer this question, it would be extremely naive to propose a single answer. However, it does seem possible to identify one factor common to all four East Asian economies in this select group. Israel will be excluded from this analysis as the author lacks the necessary country knowledge.

Eclectic policies

Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan have all had different political structures. At various points in history, they ranged from democracies to one-man, party or military dictatorships. During its period of fastest economic growth after World War II, Japan was East Asia’s only example of successful democracy. South Korea and Taiwan made the transition from authoritarian rule to full-fledged democracy as their economies modernized and their middle class grew. Singapore has always had democratic elections with its ruling party winning every time, prompting critics to allege that it limits political competition. The variance between these political systems suggests that they are not the common denominator for success.

In terms of economic policy, these countries used a wide-ranging set of tools, making it hard to put them into strictly “liberal” or “statist” boxes. Japan and South Korea, it is fair to say, were the original practitioners of 20th-century mercantilism, with tight controls over foreign trade and currency, export promotion and subsidies, import restrictions, and business-friendly labor and technology transfer policies. At the same time, cutthroat domestic competition, especially among the top conglomerates, validates these countries’ claims to being open market economies. Singapore’s economy was always very open and liberal, mostly oriented toward exports and attracting foreign investment. Taiwan stands somewhere in between.

Facts & figures

Developed and "catching-up" economies

In all these economies, state-owned enterprises played an important role, especially in the postwar period of recovery and rebuilding vital infrastructure. Even so, these SOEs largely played by market rules. While economists of all persuasions tend to focus on certain policies to classify these economies as “liberal” or “statist,” they appear to have been more eclectic in their approach, using different tools at various stages of development. Their success cannot be attributed to any specific policy mix.

While it seems that there are many paths to success, some elements do seem essential: fierce competition, especially among flagship companies, and industrial policies based on strong consultation with businesses stand out. These features of East Asian development are highlighted by many writers. However, there is another shared characteristic of these countries that deserves more attention.

Rigorous selection

At the core of these East Asian countries’ superior performance are educational systems that rigorously select the best students for civil service and top business careers.

When this factor is mentioned, there is usually a reference to the Confucian tradition’s emphasis on education and meritocratic civil service. Yet even a cursory glance at history shows this is an oversimplification at best. By the end of the 19th century, Confucianism had not produced societies that could compete with Western industrialized nations. The same Confucian system failed to produce an economic miracle in mainland China under the Kuomintang government. But after the Nationalists lost the civil war and took refuge in Taiwan, something clicked that brought the island on par with the Western industrial nations in little more than a generation.

Japan is perhaps the most striking example of an education system oriented toward selecting the best of the best.

Perhaps the most striking example of an education system oriented toward selecting the best of the best, starting all the way from junior high school and even earlier, is Japan.

Japanese kids usually attend local public schools until they finish junior high. At that stage, they undergo tough examinations to determine who gets to enter “good” secondary schools, which act as gateways to highly regarded national universities. These high schools bring together the brightest kids in a town, province or even on the national level. They are sometimes specialized by discipline, including sports and the arts.

In recent decades, so-called “escalator schools” – usually private schools that virtually guarantee acceptance for their graduates at the top universities – have extended this college preparatory track down to the junior high, elementary or even kindergarten level. As a result, the entrance exams for these institutions have become just as intensive as for the prestigious public high schools.

For the most part, only children who manage to gain entrance to these superior schools can hope to attend the very top universities. In turn, these select institutions of higher learning provide recruits to the key ministries and big companies, setting their graduates on the first rung of the upwardly mobile career ladder.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), famous for guiding Japan’s postwar economic miracle, is still the most coveted employer for Japanese university graduates. Among the dozen or so top civil service officials at METI – deputy ministers, directors-general and commissioners – an astonishing 11 attended the University of Tokyo. Most came from a single faculty: law. Even METI’s top political appointees – the minister, state ministers and parliamentary vice ministers – tend to come from either the University of Tokyo or a handful of exclusive private universities.

In this context, it is no surprise that the University of Tokyo supplied 85 percent of the ministry’s new hires in 2005. The same pattern applies to Japan’s top companies, where graduates from the top seven national and private universities virtually monopolize the senior positions.

Escalator access

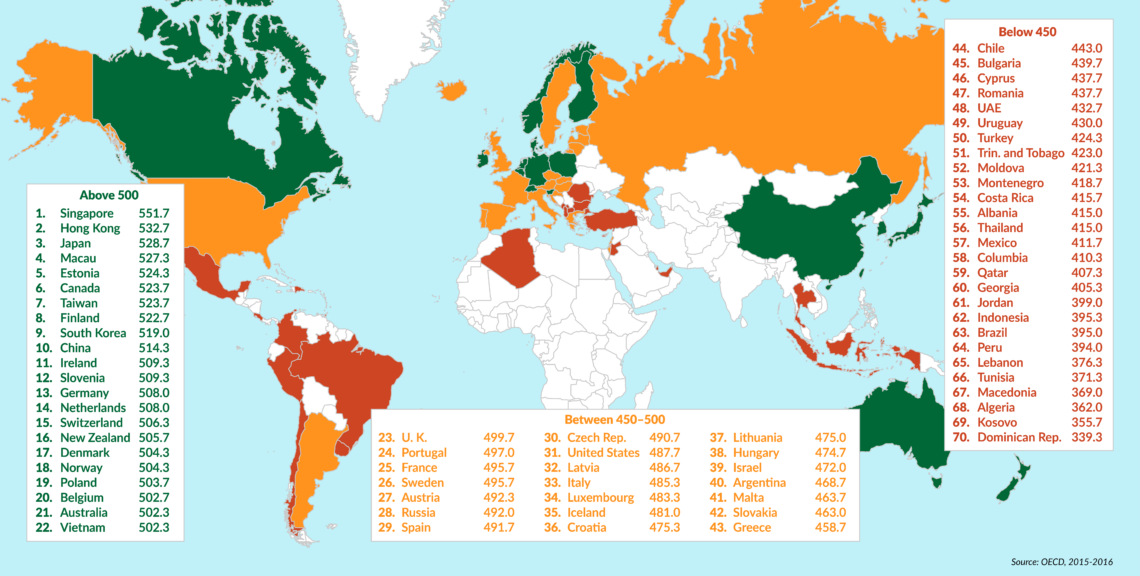

There is no doubt that bringing top performers together matters. In the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) tests, 15-year-olds from Singapore ranked first in mathematics and science, followed closely by their peers from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. The ranking is widely used as an analytical tool, since it was specifically devised by the Organisation of Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD) to provide national benchmarks for policy improvement. PISA scores have a broader significance because they provide a snapshot of the educational system’s average performance, rather than focusing only on the top achievers.

Another key point is that while private schools play an important role in Japan, the linchpin of the whole system is public schools and universities, which set the tone. This means that at least in theory, any family can have access to the “educational escalators” that enable social mobility, even though one could argue that the expense of after-school tutoring and “cram schools” are prohibitive for many.

Facts & figures

PISA worldwide ranking

Average score of math, science and reading

Once a university graduate enters the state or corporate hierarchy, promotion is based not just on accomplishment (i.e., merit) but also on seniority. There is no “fast track” allowing stars to skip over several career steps. Instead, the usual practice is to climb meticulously, one step at a time. This means that experience plays a very important role, but also that the price of getting bypassed on one promotion is career stagnation. Only those making uninterrupted, steady progress have a chance to reach the top. Hence, competition among the top performers is fierce, since a single lost opportunity closes many doors.

Japan’s “educational meritocracy” sets the bar very high, very early. Only those with a lifetime of achievement dating back to early childhood get to vie for top jobs in the public and private sectors.

Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan have adopted many features of this system. Top performers are clustered in the same schools, where they are recruited by a few national universities. Only graduates from the most prestigious schools will get recruited for good jobs in the state and corporate sectors.

China adapts

It is hard to pin down numerically the influence of educational systems on economic development. Other factors must surely have played an important role in these countries’ success. The U.S., for example, gave an invaluable boost by opening its markets to their exports, while the Cold War threat of communism served as a powerful spur to government-led modernization.

There are also plenty of negative examples. The Philippines, for example, enjoyed even more support from the U.S., yet never reached the same level as its Northeast Asian peers, despite pursuing export-oriented policies.

China chose to follow the same model used in Japanese education since its economic reform of 1978.

It is interesting that China chose to follow the same model since its economic reform of 1978. The National Higher Education Entrance Examination, or Gaokao, is a national exercise treated as an expression of one’s intelligence and aptitude; the score often determines a person’s trajectory for life.

Being accepted to a good elementary school, which leads to good junior high and high schools, is one of the most expensive items in a family’s budget, since apartments in good urban school districts cost astronomical sums. As in Japan, a handful of top institutions such as Beijing, Tsinghua and Fudan universities produce much of the country’s political and business elite. President Xi Jinping is himself an alumnus of Tsinghua University, while Premier Li Keqiang graduated from Beijing University. Most other members of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of China Communist Party come from reputable local and central universities.

At an event held by the World Economic Forum for its Young Global Leaders, the head of a global IT company’s Chinese office told how he tried to expand the number of universities from which new recruits were hired. When he arrived, only graduates from the top four national universities were accepted, so he started by inviting candidates from 100 universities. But when the recruitment process was over, he still ended up mostly hiring the same elite graduates. His conclusion was that the most suitable candidates had already been selected at a much earlier stage in their educations.

Process-oriented

Of course, politics and connections matter everywhere. In all these East Asian countries, especially at the higher levels of government and commerce, political loyalties and group ties make a tremendous difference. When the formal barriers to entry are high, however, even beneficiaries of political and personal connections must follow the rules.

Despite China’s rigid one-party system, educational performance is the key to getting a plum job. Those who get close to the top are usually, if not exclusively, among the top performers of the generation – at least in terms of educational and professional credentials – because they survived a rigorous, lifelong winnowing process.

That process seems to be the one thing all East Asian countries that have reached the level of advanced industrial economies have in common. It is now characteristic of China, too. The political and economic systems of each country might differ, but the focus on educational excellence and future careers tied to childhood performance is something that unites them all.

For this reason, day-to-day changes in Chinese politics may matter even less than is commonly thought. So long as the “educational meritocracy” hums along, the system will remain stable and keep delivering socioeconomic development. But if the Chinese leadership starts preferring pure political loyalists over high achievers, the world should start to worry. So far, there are no signs of such a profound change.