ECB: Pushing banks too far?

After the last economic crisis, the European Central Bank put in place strict rules to ensure banks were in a strong financial position. Now, to counter the pandemic’s effects, the ECB is pushing banks to take on more risks. But banks are less enthusiastic about doing so.

In a nutshell

- The ECB is trying to pump funds into the economy

- It is encouraging banks to lend by loosening rules

- Banks see medium-term risk and are reluctant

At the onset of the pandemic, central banks dreaded a drastic tightening of financial conditions. The European Central Bank (ECB) repeatedly warned that, if left unaddressed, the problem could lead to a shortage of funds available to distressed economies at a time when they were needed most. A credit crunch at such a critical moment would threaten financial stability.

What policymakers learned from the crises of the past decade is that banks can either absorb or amplify shocks to the financial system. This is particularly true in economies such as the eurozone, where banks play an outsize role. The challenge is to create the right incentives.

Credit institutions are crucial in transmitting monetary policy into the economy. However, banks have been affected by the coronavirus crisis just like any other business. If they come under too much pressure, that transmission could be impaired. That is why the ECB has resolutely targeted bank lending since March 2020.

Loosening the screws

In recent years, lending had weakened due to the strict regulatory reforms implemented in response to the 2008 global financial crisis. In early 2020, just days after the coronavirus outbreak, a new narrative emerged in EU policy circles: there should be no barriers to banks massively and rapidly lending funds, at almost no cost, to firms struggling to survive and save jobs.

The EU has encouraged banks to grant more loans to households and companies facing economic hardship.

For a start, capital and other regulatory requirements, which over the past years have weighed heavily on the European banking sector, were temporarily eased. The ECB has even encouraged banks to fully use their capital and liquidity buffers to grant more loans to households and companies facing economic hardship during lockdowns. According to an estimate by the advisory firm KPMG, 120 billion euros in extra bank capital could thus be freed up for new lending operations.

The ECB has invited banks to ease their credit standards in return for more leniency on their nonperforming loans (NPLs). It also granted banks more flexibility on supervisory timelines, notably reporting deadlines and procedures.

To cope with the urgency of the health crisis, the ECB’s banking authorities are ready to move further and further into uncharted territory. Even international standard setters such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision recently called for relief measures at the national and supranational levels. To prove its good faith, the committee postponed implementation of the Basel III framework’s most stringent rules.

Lucrative losses

Another detrimental consequence of post-global financial crisis reform is the environment of ultra-low or negative interest rates in which banks now operate. Over the last decade, banks’ interest margins have shrunk to virtually nothing. To make up for the shortfall, banks implemented cost-cutting and fee increases, but these reached their limits long ago. A lot of eurozone banks still struggle to keep their business models viable. Few could recover to pre-2008 profitability. In its April 2020 Global Financial Stability Report, the International Monetary Fund warned that banks may not be profitable before 2025, even as major economies recover from the Covid-19 recession.

The ECB’s main policy rate (the so-called deposit facility rate) currently stands at -0.5 percent. As President Christine Lagarde recently confirmed, a further rate cut is not on the table, since it would place additional strain on bank profitability. Nonetheless, the pressure to drive down borrowing costs (and thus the interest rates borrowers pay) is immense. Since March, in response to the health crisis, the ECB has been providing colossal liquidity support to the economy.

Facts & figures

For example, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP), with its envelope of 1.85 trillion euros, comes in addition to the ongoing Asset Purchase Program (APP), which for years has been one of the ECB’s most powerful monetary accommodation tools. The APP, running at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros, has received another temporary 120 billion-euro envelope, to be deployed by the end of the year.

On one hand, the flow of money from the ECB significantly improves banks’ liquidity positions. On the other, it further deteriorates their profitability. Quantitative easing, largely responsible for the low-for-long short-term interest rates, has become a thorn in bankers’ side. To compensate lenders for the losses they incur from the low rates, in 2014 the ECB put in place various rounds of so-called targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), which basically pay banks for lending to the real economy. In March 2020, the TLTRO III series was recalibrated so that lenders, if they agree to fully play their part, can benefit from rates as low as -1 percent.

The ECB also decided to conduct a series of additional (nontargeted) pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs), allowing participating banks to benefit from a considerable easing in collateral standards for lending activities. A much broader set of assets is now accepted as collateral, including some loans to small and medium-sized enterprises or self-employed workers. So far, the ECB is making up to 3 trillion euros in liquidity available for banks through this highly lucrative alphabet soup.

Finally, the ECB, within its traditional role as lender of last resort, provides solvent banks with a safety net called emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). Through this tool, enormous amounts of liquidity can be mobilized over long periods by banks facing temporary difficulty, at the rate of -0.5 percent, “without any conditions attached.”

High hopes

We are told time and again that these are unprecedented measures for unprecedented times. It may be early to assess their full effectiveness and eventual side effects. Their success or failure may ultimately depend on whether banks are willing and able to return the favor by assuming their role as carriers of the ECB’s monetary stimulus.

The new uncertainties translated into another sharp drop in economic activity.

A team of ECB economists recently asserted that the mix of ultra-expansionary monetary policy and prudential relief implemented since last March promptly bore fruit. Between June and August, 742 eurozone banks had already taken up the ECB’s offer for three-year loans under TLTROs, for a total of 1.308 trillion euros. This alone allowed for a net liquidity injection of 548.5 billion euros into the real economy, according to ECB executive board member Isabel Schnabel.

Economic figures presented at the ECB’s mid-July monetary policy meeting indicated that the eurozone (some countries and sectors more than others) was showing signs of recovery, as lockdowns and other restrictions were eased. Even though the growth momentum over the summer did little to make up for the enormous losses earlier in the year, it could have foretold a rather encouraging autumn – had it not been for the second wave of Covid-19 infections that hit Europe in October.

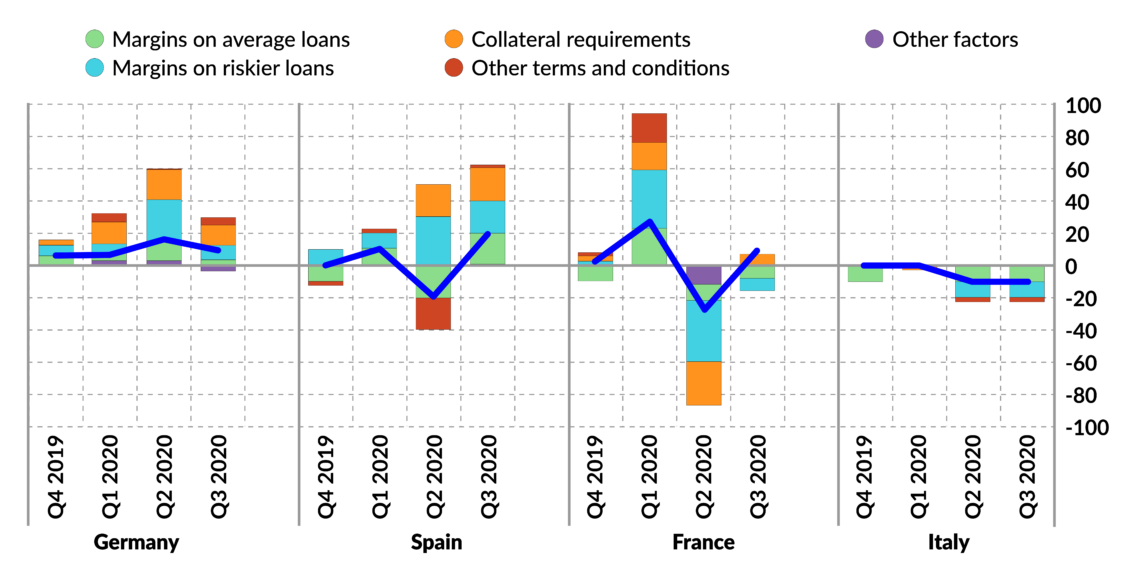

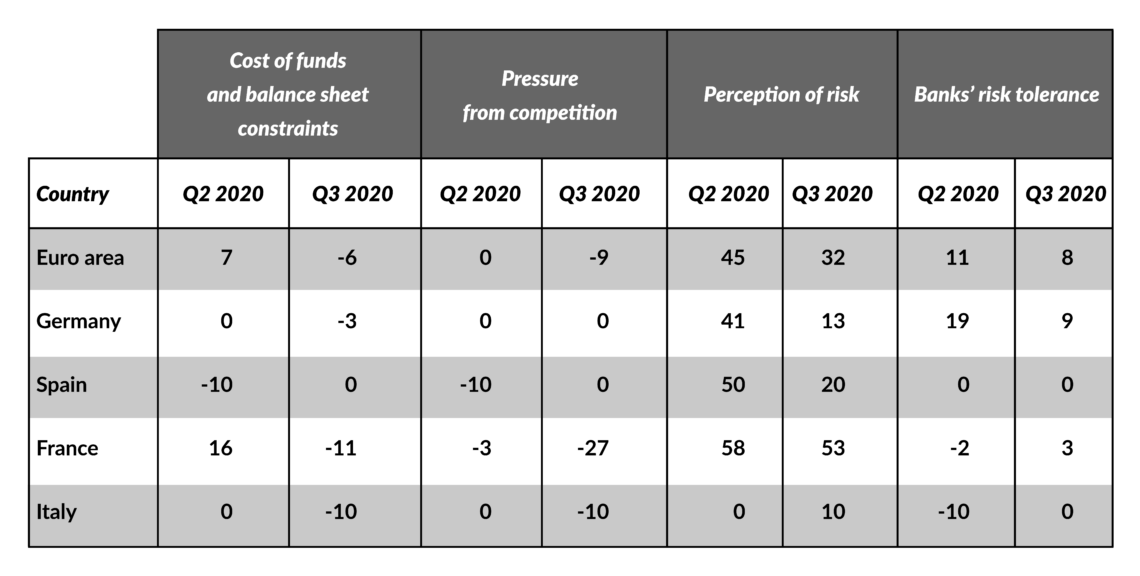

In its two euro area Bank Lending Surveys (BLS) of April and July, conducted amid the first peak of the health crisis, the ECB highlighted a sharp surge in companies’ demand for loans or drawing of credit lines, mostly due to emergency liquidity needs. The situation justified the full deployment of the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy arsenal: loan supply had to keep up with the drastic spike in demand. At first, banks seemed to play their part by increasing lending volumes, if less than the ECB would have liked. Most of the 144 banks that the ECB surveyed said they had tightened their credit standards for loans to households, while keeping those for firms broadly unchanged. The rejection rate of loan applications decreased for firms but increased for housing loans and consumer credit.

Rational recalcitrance

The second coronavirus wave brought new restrictions, lockdowns and curfews. The new uncertainties promptly translated into another sharp drop in economic activity.

Banks adjusted their lending behavior right away, as the ECB’s October 2020 BLS confirmed. While trying to reassure markets that everything is still under control, the report reflects a slightly more worrisome scenario than those projected in April and July.

Facts & figures

The criteria that banks use to approve loans have considerably tightened, notably in Germany, France and Spain. Lending criteria have become tougher not just for households, but for companies – of all sizes – as well. The tightening concerns both short- and long-term loans. The rejection rate for all loan applications has increased significantly.

Perhaps more surprisingly, bankers seem to have lost their appetite for the instrument most favorable to them: TLTROs. In June, 78 percent of the surveyed banks had taken advantage of TLTRO III, but in September the figure had dropped to only 35 percent. Of those banks, just 17 percent intend to participate in future TLTROs.

Banks’ changing attitude could be due to growing anxiety about the economic outlook. As hopes for a short-lived pandemic and a quick recovery faded, financial institutions began looking to the medium term and adapted their risk models accordingly – a completely rational decision. By tightening lending terms, banks are looking after their own survival. The question is whether their more prudent stance is throwing a wrench in monetary authorities’ plans.

Hit from all sides

More than anything, banks have less tolerance for risk because borrowers’ creditworthiness has deteriorated. They worry that large-scale insolvencies or bankruptcies among over-indebted clients could lead to heavy losses.

Meanwhile, their own capital positions have worsened. Since the global financial crisis, they have worked hard to clean up their balance sheets and get rid of toxic assets. Over the years, they have become more resilient to financial shocks, as EU-wide stress tests have confirmed. But now they are being encouraged to pile up new mountains of nonperforming loans, which might adversely affect not only the quality of their assets but the performance of their stocks.

At some point, European banks must rebuild their capital buffers. This will be no small task, even in the best-case scenario.

European bank stocks have already taken on major losses in recent months. Back in March, their bond prices came under pressure too, which could indicate that investors have started to worry about the health of eurozone banks. Notably, some major French banks that hold large amounts of Italian sovereign debt were hit hard by market turmoil.

At some point, European banks must rebuild their capital buffers. This will be no small task, even in the best-case scenario, with Europe avoiding severe, long-lasting economic scars. Banks that were already undercapitalized going into the pandemic, and/or operate in eurozone countries with little fiscal room for maneuver, will find building back their buffers even more difficult. After the last crisis, it took more than a decade to regain the sector’s resiliency.

Stress factor

The ECB’s October analysis anticipates a further tightening of bank lending standards, and, consequently, a decrease of lending volumes by year-end. If the January 2021 survey confirms this trend, it would be bad news for the ECB’s policymakers, who seem to see no other option but to provide liquidity to the distressed economy.

On December 10, the ECB announced further stimulus measures. Among others, it increased the PEPP’s envelope by 500 billion euros, bringing it to the above-mentioned total of 1.85 trillion euros. The horizon for net purchases under PEPP has been extended to at least March 2022.

Monetary authorities expect banks to play a countercyclical lending role. But in doing so, are they putting the banking system under too much stress? This question is worth asking at a time when euro area banks, in a desperate search for profitability, stand at a fork in the road. Will they take the cautious route, or the riskier one? Either scenario could endanger Europe’s financial stability.