Causes and consequences of the dollar’s weakness

The U.S. dollar has weakened significantly since March 2020, surprising many observers. Some of the drop can be ascribed to the diminished international trade flows. There may also be, however, more disturbing reasons lurking beneath the dollar’s weakening figures.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. dollar has weakened against the euro and other key currencies

- Demand for the dollar has lessened with the slowdown in global trade flows

- Investors’ trust in the soundness of U.S. monetary policy is shaky

By the beginning of March 2020, it was clear that the Covid-19 threat had been underestimated, that most governments were unprepared for the pandemic and that the decisions that were to follow would profoundly affect many economic variables. Understandably, few paid much attention to exchange rates.

Although many observers had been expecting a weaker United States dollar since the fall of 2019 – a prediction that had nothing to do with the disease – two schools of thought emerged in early March. One camp argued that a substantial rise in U.S. public debt would lead prospective foreign investors to demand more dollars for purchases of American treasuries. Others believed that if the Fed engaged in ultra-generous monetary policy, international markets would be flooded with greenbacks. Hence, the dollar exchange rate would drop. Now, we know what actually has transpired.

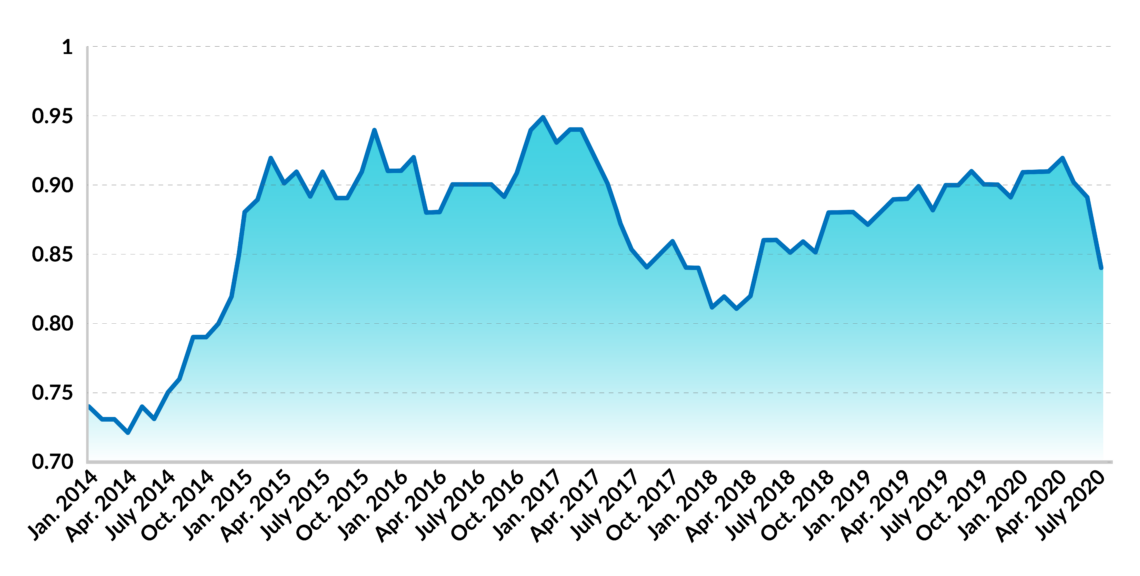

The slide

During the past five months, the dollar has weakened about 10 percent against the basket of major world currencies and, by a lesser rate, against the euro. The benefit of hindsight makes it easy to explain why.

Interest rates show there was more room for monetary profligacy in the dollar area than in the eurozone.

Since international trade flows have declined (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, or UNCTAD, forecasts a 20 percent reduction in 2020), the demand for the main world exchange currency – the U.S. dollar – has also declined. Moreover, a comparison of the precrisis levels of interest rates shows that there was more room for monetary profligacy in the dollar area than in the eurozone. Policymakers would not have missed an opportunity to spend more.

Finally, surging public deficits and debts in the eurozone countries have probably fed expectations of a rapidly rising demand for euros. While Brussels and Frankfurt have responded to the crisis by resorting to public debt, Washington has emphasized easy money and credit. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell repeatedly made it clear that he would do whatever it takes to expand the money supply. The president of the ECB was much less vociferous. Hence, the dollar has dropped, while the euro has risen.

What now?

Is this good news or bad news? And what can we expect for the future? In brief, it is moderately good news from a short-run viewpoint and probably bad news from a longer perspective.

In the short run, a weakened dollar should make U.S. companies happy (a weak dollar makes American goods and services more competitive). It may also discourage President Trump from unleashing a global trade war by accusing the rest of the world of manipulating their currencies. Some caution about this prognosis is in order, however.

Mr. Trump has recently raised tariff barriers on a number of imports from the European Union, especially France and Germany. Likewise, even though the U.S. dollar has fallen by about 10 percent against the Canadian dollar since last March, President Trump announced in early August a 10 percent tariff on aluminum imports from Canada for the benefit of Ohio’s aluminum industry. (Ohio is one of the so-called “swing states” that could vote Democratic or Republican and might play a vital role in the November elections).

Under normal circumstances, a weak dollar and ultra-low interest rates are also an unexpected bonus for many developing countries that borrowed in U.S. currency during the past decade. Once again, some qualifiers are due. A relatively strong dollar and less distorted interest rates would have forced many bad borrowers into default and their creditors to accept losses. Yet, solvency provided by a weak dollar is not necessarily welcome.

The U.S. has failed to keep the spread of Covid-19 under control and more trouble lies ahead for its economy.

Some borrowers have misused resources and wasted opportunities. More debt servicing and debts bode ill for in the future. Indeed, the future might not be far away if the borrowers’ traditional export markets shrink or trade restrictions become more acute. In other words, kicking the can down the road might appeal to creditors, but prevents debtors from coming to grips with past mistakes, implementing badly needed economic and political reforms, and possibly having a fresh start when the overall situation improves.

Scenarios

In the long-term perspective, the weakened dollar suggests two different scenarios.

One may believe that investors are moving away from the dollar because they are persuaded that the U.S. has failed to keep the spread of Covid-19 under control and more trouble lies ahead for its economy. The rate of unemployment is falling less sharply than anticipated (it was 10.2 percent in July) and the hoped-for V-shaped rebound failed to materialize. The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to drop 5 percent in 2020 and rise “only” 2 percent in the following year.

Following this line of reasoning, one can claim that optimistic expectations about the U.S. economy had sustained the dollar until mid-February and that the current exchange rate simply shows where the dollar should be as America has proven no better than most countries in dealing with the pandemic.

A different scenario opens up if one takes a broader look at the monetary responses to the pandemic. The typical fundamental message sent out by central banks is clear: when the economy is in trouble, do not hesitate to expand the money supply and ease credit. This is the key prescription of the so-called Modern Monetary Theory, according to which policymakers should print all the money required to obtain the desired rate of economic growth and worry only when inflation becomes practically intolerable.

Paradigm change

If this is the case, then the drop in the dollar exchange rate reflects the loss of credibility of the only currency considered a haven and an anchor for the global monetary system. This would be the end of an epoch.

Facts & figures

For more than 70 years, the dollar has been the reference point for all currencies. Despite numerous questionable policy moves undertaken by the Fed during the past decades, policymaking in most advanced countries was governed by the strength and weakness of the local currency with respect to the dollar. All this might come to an end if the Fed continues to indulge in unrestricted money printing. Within this framework, the dollar’s slide is the result of a lack of trust and disillusion about U.S. monetary policy.

The line of reasoning presented may serve as a crystal ball for interpreting future developments. Although the phenomena described will influence the situation, the dollar is unlikely to bounce back to its previous levels pretty soon. Here is why.

Arbitrary money printing will be the name of the game as long as people are frightened and refrain from spending

In the recent past, the euro suffered from intense euroskeptic pressure, which threatened to tear apart the entire European political project. As much as one may criticize Brussels’ and Frankfurt’s responses to the coronavirus challenge, the danger of an imminent EU collapse has now clearly receded.

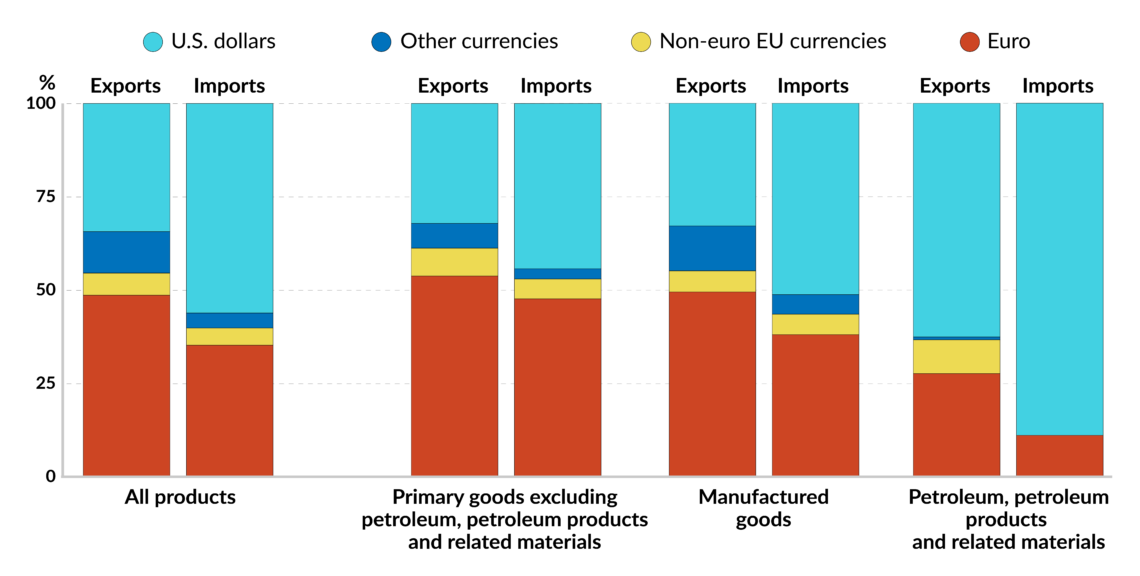

The euro is certainly not a haven. Yet, it is no longer a risky currency. On the other hand, the dollar is no longer a high-quality currency, nor is it a haven. However, the lack of a credible substitute and the still crucial role of the U.S. in international politics ensure that the greenback remains the key legal tender in international transactions and a store of value. This explains why there will be no massive run away from the dollar.

Regardless of what will transpire, it seems that modern monetary theorists have won the day, at least for the time being. If this trend continues, arbitrary money printing and systemic instability will be the name of the game as long as people are frightened and refrain from spending. Should the world economy go back to some normalcy at some point, however, then we had better brace ourselves for inflation.

This would be particularly problematic. Most policymakers have no idea how to deal with such a scenario. The recipes put forward by the modern monetary theorists – higher taxation to take the heat off the economy – are downright scary. Further moves toward some form of central planning or “harmonized” international regulations lurk around the corner. Luckily, there is still time to change tack. Once the pandemic dust has settled, policymakers will hopefully think again, develop new visions and act accordingly.