Question marks over the ECB’s governance

Growing doubts over the stimulus policies of the ECB combined with ignoring dissenters among the bank’s governors and executive board members bode ill for the longer-term effectiveness of this critical European institution and its leadership. New ECB President Christine Lagarde may not yet appreciate the problem.

In a nutshell

- The early departure of another high-level European Central Bank official has confirmed tensions in the critical European institution

- The disagreements stem from both the policies and leadership style of the bank’s former President Mario Draghi

- The new ECB leader, Christine Lagarde, may face a weakened opposition but the problems are unlikely to go away

On September 12, 2019, Mario Draghi presided for the penultimate time over the monetary policy meeting of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB). The Italian’s eight-year mandate expired on October 31, but the era of cheap money he stands for is far from over.

At the press conference in September, following what observers called the most heated ECB meeting in years, the outgoing president announced a range of new, far-reaching stimulus policy measures. Among them were a further cut of deposit rates (from -0.4 to -0.5 percent) and a reopening of the controversial expanded asset purchase program (APP) for “as long as necessary,” with another round of net bond-buying to start on November 1, 2019, at a pace of 20 billion euros per month.

As planned, the ECB will also continue reinvesting payments from maturing securities purchased under the previous APP, launched in early 2015 and closed in December 2018. Also, subsidizing banks through “targeted longer-term refinancing operations” (TLTRO III) will be strengthened to further improve lending conditions.

Resignation

On 25 September, Sabine Lautenschlaeger, one of the most ardent opponents of Mr. Draghi’s stimulus policy within the ECB, handed in her resignation. Her time on the Bank’s Executive Board and Governing Council (in which six Executive Board members sit by default; the rest of the body comprises central bank governors of the 19 euro area countries) ended on October, the same day that Mr. Draghi retired. Her decision to quit, two years before the end of her term, took everyone by surprise.

Ms. Lautenschlaeger cited “professional” grounds for her decision. In an email to staff, she argued that leaving the bank was the “best course of action,” given the “situation” in which she found herself.

The vacancy created an embarrassing boardroom impasse, as Mr. Draghi was not able to replace her for months.

The ECB’s communique announcing her early departure did not reveal any details either. It confined itself to a terse acknowledgment of Mrs. Lautenschlaeger’s “instrumental role” in “helping set up and steer Europe-wide banking supervision,” notably in her role as the vice-chair of the Supervisory Board, a position she held since the creation in 2014 of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). Her mandate in this body, which directly oversees the euro area’s 119 largest banks and indirectly all the others, ended in February 2019. Back then, the vacancy created an embarrassing boardroom impasse, as Mr. Draghi was not able to replace her for months. Luxembourger Yves Mersch was finally chosen. His nonrenewable eight-year term on the Executive Board runs out in 2020.

Point of no-return

The press usually underlines that Ms. Lautenschlaeger is the fourth top-level official from Germany to quit the ECB governing body over disputes on monetary policy. Between 2011 and 2012, her council colleagues Joerg Asmussen, Axel A. Weber and Juergen Stark had resigned before the end of their terms in dismay over the bank’s early bond-buying programs.

Facts & figures

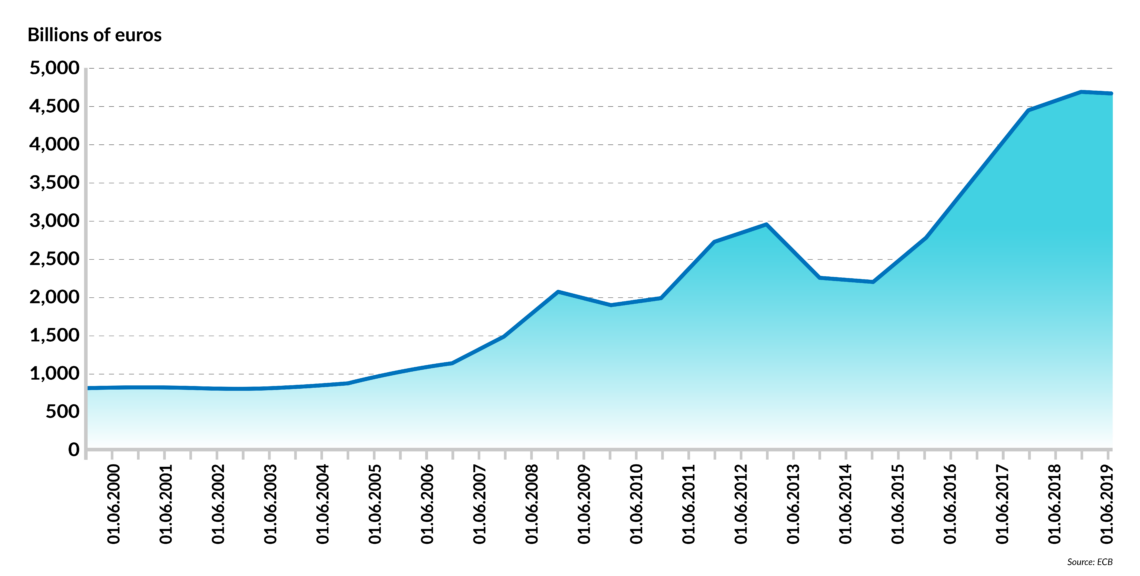

The European Central Bank's balance sheet

Ms. Lautenschlaeger’s opposition to expansionary monetary policy is not new. Back in 2015, she warned that quantitative easing (QE) merely “buys time but does not heal structural causes of a slack economic recovery.” As the ECB Governing Council went on and on with this policy, pumping, through the APP alone, over 2.6 trillion euros worth of liquidity into the European economy in less than four years, she made herself heard. Obviously, however, she never envisaged resigning in protest.

Why do so now? If she wanted to keep up the fight against what she considers insanely loose monetary policy, would she not be far more useful inside the ECB? If her differences with Mr. Draghi had reached an unbearable point, she might as well have taken a few weeks off, and waited until he had gone. One reason might be that she anticipated her relationship with Christine Lagarde, former chief of the International Monetary Fund who was appointed the new ECB president, would have gone just as badly. Little is known about how the two women get along.

In any case, when a renowned fighter like Ms. Lautenschlaeger throws in the towel, it can only mean one thing: the 55-year-old supervisor does not believe in the institution anymore. Witnessing that the internal opposition no longer leads anywhere, she might think she could be more effective acting from the outside, unbound from ECB-imposed confidentiality and other contractual clauses.

In other words, her resignation does not necessarily imply she is worn down or demoralized by what the Neue Zurcher Zeitung called the “Draghi system,” which she may expect to live on under Ms. Lagarde.

At a recent European Parliament hearing, the latter indeed confirmed that, although “mindful about potential side effects,” she would continue with her predecessor’s “highly accommodative monetary policy” for a “prolonged period of time.” Actually, Mr. Draghi, by relaunching QE just six weeks before Mrs. Lagarde took over, did not leave her much of a choice.

The September 12 meeting almost turned into a mutiny, as several central bank governors decided to break ranks

For the moment, one can only speculate that, after a mandatory cooling-off period (as determined by Article 17 of the Code of Conduct for high-level ECB-officials), Sabine Lautenschlaeger may plan to return to the Bundesbank, which is far more oriented toward orthodox monetary policies. There, she might actively join President Jens Weidmann’s battle against the ECB’s policy stance.

Fracture line

For years, Dr. Weidmann has been the most vocal hawk within the group of Governing Council members who regularly break with ECB etiquette by publicly throwing sand in the wheels of Mr. Draghi’s unconventional presidency. Reportedly, the September 12 meeting almost turned into a mutiny, as several central bank governors decided to break ranks. For Mr. Weidmann, the ECB has “gone overboard;” the Austrian central banker Robert Holzmann spoke of a “mistake.” His fellow-governor Klaas Knot published a statement on the website of De Nederlandsche Bank, arguing that the new package of measures was “disproportionate to the present economic conditions” and there were “sound reasons to doubt its effectiveness.”

Among the usually more prudent and consensual Governing Council members, Francois Villeroy de Galhau (Banque de France) and Benoit Coeure (Executive Board member) raised concerns about a policy whose negative side effects (overheating of the northern euro area economies and risks of debt traps in the south) keep increasing with each round. All insist that with every new package of multibillion stimulus, the likely unavoidable withdrawal of QE becomes harder, costlier and riskier in terms of financial stability.

The Estonian governor and, to a lesser extent, Slovakia’s central bank chief, also expressed discontent, while the head of Luxembourg’s (the euro member most affected by the buildup of asset bubbles, in particular in real estate markets) did not comment.

According to a recent hawk-dove classification, the ECB Governing Council currently counts nine advocates of loose monetary policy (the most dovish being Finland and Italy), eight hawkish defenders of tight monetary policy, and seven whose status is uncertain or unknown.

Solitary leadership

As the gap widened between the council hawks and doves – and, more importantly, between the interests of northern and southern member states – former President Draghi kept up his legendary poker face. He did not need consensus to make good decisions, he implied in an interview with the Financial Times, conducted shortly before Mrs. Lautenschlaeger slammed the door.

Mr. Draghi told the paper that the July 2012 London speech, in which he famously declared he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, had been “a defining moment” for him. At the peak of the European debt crisis, the ECB president’s solemn commitment to stabilize sovereign bond markets through the schemes of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) had taken everyone by surprise. It was essentially his decision – many were against it at the time (Mr. Weidmann was at the forefront of critics outraged by what they considered a trespassing of the ECB’s mandate), but it proved useful in that context. It certainly confirmed Mr. Draghi as an exceptionally visionary ECB leader.

From that day on, he no longer felt the need to seek unanimous support for his actions, even in the most critical situations. The search for unanimity could indeed be a barrier to efficient governance of a panel representing conflicting (if not irreconcilable) national interests. To the question of how many among the Governing Council’s 25 members early on in the September 12, 2019 meeting were against restarting massive QE, Mr. Draghi replied: “I can’t tell you the number,” before insisting “there was no need to take a vote,” because there was a “significant majority.” The decision made clear once again that as long as he thought it was the right policy, he would go through with it.

The question, however, is this: What made Mr. Draghi think that QE was the best policy in the 2019 context? Was there evidence it had worked?

Strategic rhetoric

Since Mr. Draghi took over the ECB in late 2011, trillions of euros in liquidity have been injected into the distressed eurozone economies and, meanwhile, interest rates had fallen noticeably below zero. Nonetheless, inflation remained far from the predetermined target of “below but close to 2 percent,” and growth forecasts for 2020 and the next years were just as mediocre.

In terms of policy preferences, Isabel Schnabel is considered not nearly as hawkish as Ms. Lautenschlaeger.

Year after year, the ECB had missed most of its policy targets, as finance watcher Positive Money recalls. Also, for six consecutive years, the bank’s outlook on the current and future economic situation, at the basis of its monetary policy decisions, largely has been proven wrong. Macroeconomic projections have been downgraded since 2017, a year in which the eurozone growth had reached a 10-year high – before declining again, despite the most favorable lending conditions ever.

So, why cling to a monetary policy that obviously no longer works?

The answer provided by the ECB’s chief economist and Executive Board member Philip Lane in a recent interview appears astonishingly redundant: “[T]he world needs to understand that we will be responding to these significant downgrades by making sure the monetary conditions are sufficient; to make sure the momentum of getting inflation back towards our target is restored.”

In a spirit of unabridged optimism, Mr. Lane added: “Our assessment is that our tools remain quite effective”. His sole objection to the ECB’s current “super-easy”-monetary-policy stance: “well actually maybe we need it even looser.”

Free rein

EU officials promised to name promptly Ms. Lautenschlaeger’s replacement on the six-person ECB Executive Board. The “ideal” candidate was supposed to be a German (by convention, the three major eurozone economies, Germany, France and Italy, always occupy one seat each), an economist and, preferably, a woman. By October 24, the deadline for eurozone governments to submit their candidates, the name of Isabel Schnabel, a professor at the University of Bonn and member of the German Council of Economic Experts, was put forward by Germany as the only candidate. In terms of policy preferences, she is considered not nearly as hawkish as Ms. Lautenschlaeger.

Eventually, the eurozone finance ministers will also name a replacement for Yves Mersch as second-in-command of the SSM, and revive the important bridge between banking supervision and monetary policy on which Sabine Lautenschlaeger made her name.

In any case, the ECB Board can be expected to become even more dovish after the departure of Benoit Coeure at the end of 2019 and Mr. Mersch one year later. This would facilitate the task of reconciliation for Mrs. Lagarde, who has promised, in front of the European Parliament, to “listen to all voices” and “foster diversity of thought.”

Hopefully, some commentators are going too far by stating that the ECB, rather than benefitting from internal debate (as one could expect from a mature institution), is moving ever closer to an “all-out war.”

Nonetheless, Mrs. Lautenschlaeger’s empty chair could give Mrs. Lagarde a freer rein to pursue Mr. Draghi’s ultra-accommodative policy without much resistance at least within the Executive Board. And even, as urged by Mr. Lane, allow her to go significantly deeper into the territory of negative interest rates.