Ecuador picks up the pieces

Ecuador is a small country that embodies many of Latin America’s issues in miniature. Overdependence on commodity exports and tensions with the U.S. are just some of them. Its government must clean up after former President Correa’s failed “Citizens’ Revolution,” trying to build institutions on a legacy of personalistic governance.

In a nutshell

- Ecuador encapsulates many of Latin America’s current policy debates

- President Lenin Moreno is shifting away from his predecessor’s free-spending ways

- The government is also trying to reduce dependence on Chinese trade and investment

- This transition is politically ticklish and has already split the ruling coalition

Ecuador is a small country, with a population just under 17 million and an economy that generates a bit over $100 billion in goods and services. It does not have the soft power aspirations of Uruguay or Costa Rica, two other small countries in Latin America. Yet, at the moment, Ecuador seems to be the perfect model for studying the cross-currents – international, political, economic, and social – that are battering countries throughout the region.

Ecuador is a multiracial society – 25 percent of the population is indigenous, 55 percent is mestizo, 10 percent is of African descent, and only 10 percent considers itself white or Caucasian. The country’s economy depends on the production and export of primary products. Like several of its regional peers, Ecuador is deeply indebted to Chinese firms developing its infrastructure and relies on Chinese buyers for its export commodities, particularly petroleum.

Most important, it is a country now immersed in Latin America’s crucial policy debates: how to balance sound institutions versus personalistic governance, reduce poverty while staying fiscally responsible, and maintain good relations with neighbors and global powers, including China and the United States.

Like other small countries, Ecuador cannot escape geography. It is wedged between Colombia and Peru, the world’s two largest producers of cocaine. All three are Pacific, Andean and Amazonian countries. All are multiracial. Ecuador has received thousands of former guerrillas from Colombia who are unhappy with the peace process in that country, turning the border area into a conflict zone and allowing organized crime groups – known as BACRIM in Colombia – to create havoc in northern Ecuador. Over the past year, an even bigger strain has been imposed by hundreds of thousands of migrants from Venezuela.

Pink tide

After decades of political instability and mediocre economic growth, in 2007, Rafael Correa put together a coalition of forces he called Alianza PAIS (Proud and Sovereign Fatherland Alliance) that won the presidency and a majority in the national legislature. Mr. Correa was an economist with a doctorate from the University of Illinois, where he studied development with the legendary Werner Baer. He came to power in the middle of the boom in commodities prices that brought a massive windfall to nearly every government in Latin America.

President Correa’s platform called for a “Citizens’ Revolution,” and once in office, he immediately began to use the new abundance of resources to distribute wealth, provide government subsidies to people in need, and invest in the country’s infrastructure. The latter program was rather grandly called Changing the Country’s Productive Matrix and Changing the Energy Matrix. Such ambitions were in tune with those of other leftist leaders in the region, who also came to power on promises of sweeping changes.

The Correa government severed long-standing ties with the U.S. and turned to China as a strategic partner.

As part of that “pink tide,” Mr. Correa joined ALBA, the anti-U.S. alliance put together by Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, and played a leading role in the consolidation of the Union of the South American Nations (UNASUR), even agreeing to build a secretariat for UNASUR in Quito. Mr. Correa severed long-standing ties with the U.S. and turned to China as a strategic partner in his drive to modernize Ecuador.

These foreign policy decisions were called into question when Mr. Chavez died in 2013 and Venezuela’s statist economy began to crumble. ALBA lost its momentum, while UNASUR was weakened and then shut down by the advent of conservative governments in Argentina and Brazil – leaving as a monument its empty secretariat building in Quito. In the long term, President Correa’s foreign policy came to be overshadowed by the domestic political debate over his increasingly evident authoritarian tendencies.

Authoritarian tilt

In 2012, as President Correa’s first term in office was ending and he was poised for reelection by a comfortable majority, he set out to muzzle his opponents in collective organizations and social movements while reducing the space for democratic contestation. Among his methods were threats against the news media and attempts to curb the powers of other state actors, especially the judiciary and the military. There was a marked tilt toward authoritarian populism.

From a formal point of view, the judiciary remained independent; but President Correa’s control over the nominating mechanisms and his direct intervention undermined that independence. The Global Report on Competitiveness by the World Economic Forum (2017) ranked Ecuador 134th out of 138 countries in terms of judicial independence. In one dramatic instance, the government was implicated in the 2010 murder of its own air force commander, General Jorge Gabela, who had opposed a $50 million contract to purchase Indian-made HAL Dhruv helicopters, which he considered unsafe. A subsequent report by the investigating judge suggested that the murder was organized by the country’s intelligence agency.

Facts & figures

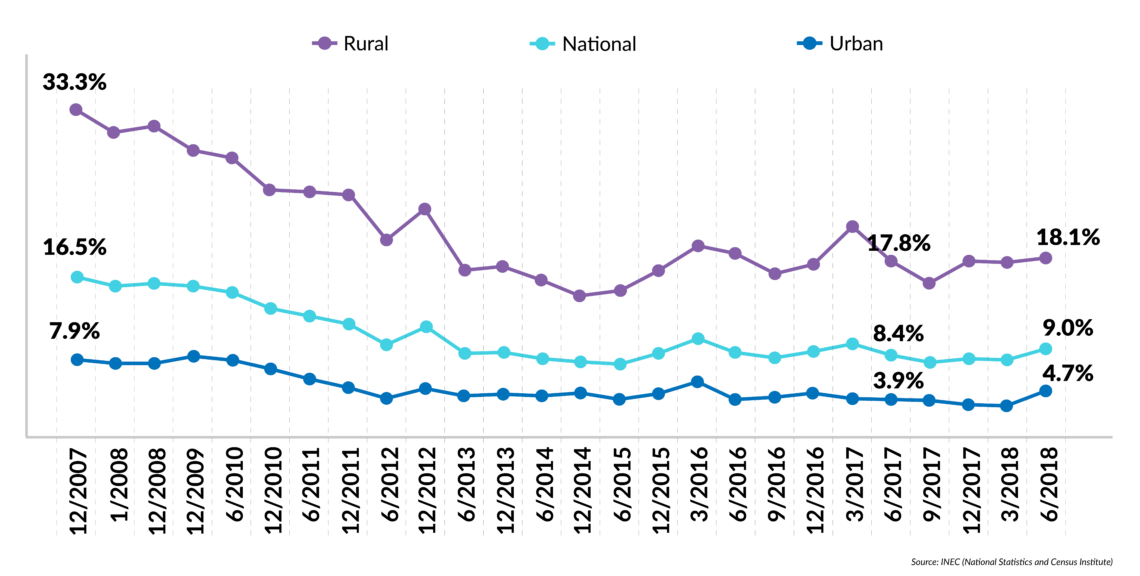

Extreme poverty in Ecuador

The combination of massive social programs under the Citizens’ Revolution and a veritable flood of infrastructure projects, especially ambitious hydroelectric projects, funded by Chinese state banks and built by Chinese companies, unleashed a huge spending spree. Ecuador’s poverty rate fell dramatically, and many who had suffered from economic exclusion were at last able to find work.

Unfortunately for Ecuador and for Mr. Correa, that spending did not stop when the prices of petroleum and other commodities suddenly came crashing down after 2010. By President Correa’s second term, the country’s financial situation – its budget deficit, sovereign debt and current account deficit – had become untenable. Adding to his difficulties was the accumulating weight of political scandals, including General Gabela’s murder, the abduction of an opposition legislator, and corruption involving contracts awarded to the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht.

Three choices

Whether it was because he saw the writing on the wall or simply because it was unconstitutional, President Correa decided not to seek a third term in 2017. His designated successor, Lenin Boltaire Moreno, had served as vice president during Mr. Correa’s first term and gave all the signs of being a loyal follower of the social democratic agenda. During the April 2017 presidential runoff, Mr. Moreno edged out his conservative rival from the coastal city of Guayaquil, Guillermo Lasso, 51.2 percent to 48.8 percent. His four-year term runs until 2021.

From the start, President Moreno gave signs he would not follow his predecessor’s lead. His split with Mr. Correa was based upon three policy decisions, each with consequences for the others. The first to be announced was a shift in fiscal policy. The new government acknowledged that continuing to borrow and spend while commodity prices were depressed would soon lead to financial collapse. The state would have to spend less and shrink, while reaching out to the private sector – never a fan of Mr. Correa’s – to stimulate investment and revive a stagnant economy. Accordingly, the new government’s very first legislative measure was called the “Production Development Act” (Ley de Fomento Productivo).

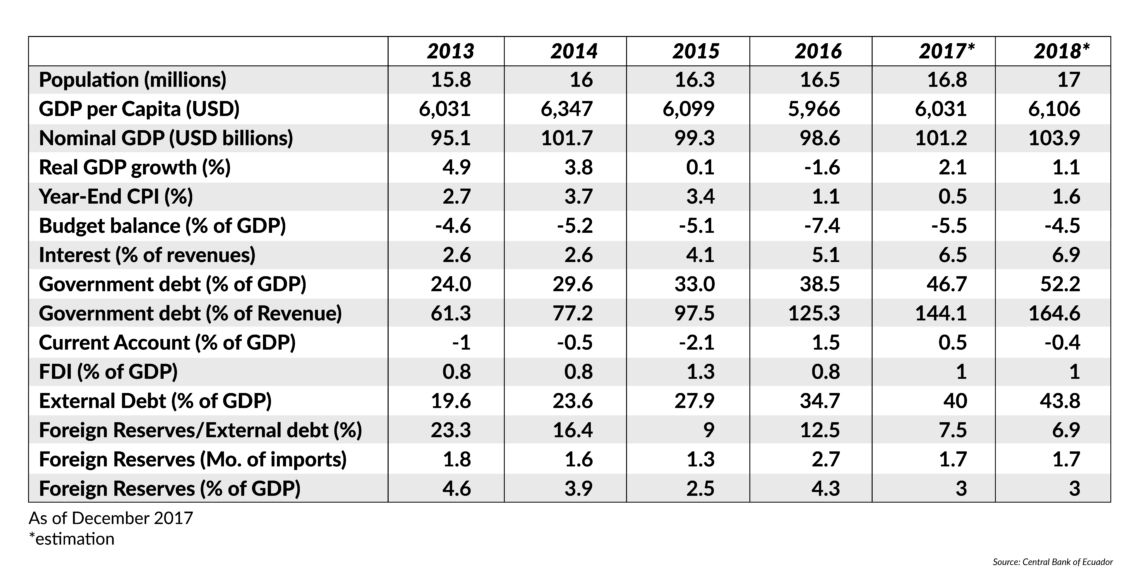

Facts & figures

Ecuador's key indicators

The second strategic decision was to pull back from Mr. Correa’s personalistic, semi-authoritarian posture and start a “National Dialogue” to bring all sectors of society into a discussion of national priorities in a time of scarcity. Besides business groups, President Moreno reached out to organizations representing civil society and the indigenous population that had been hostile to the previous government.

The third policy choice concerned foreign policy. Mr. Moreno wanted to make it very clear that he had no interest in continuing ALBA or maintaining close ties with Venezuela and Cuba, or in any actions that set Ecuador at odds with the broader hemispheric community. He needed to get back into the good graces of international lenders, especially the U.S., to help fuel the economic recovery and wean the country from its dependence on Chinese trade and investment.

Split majority

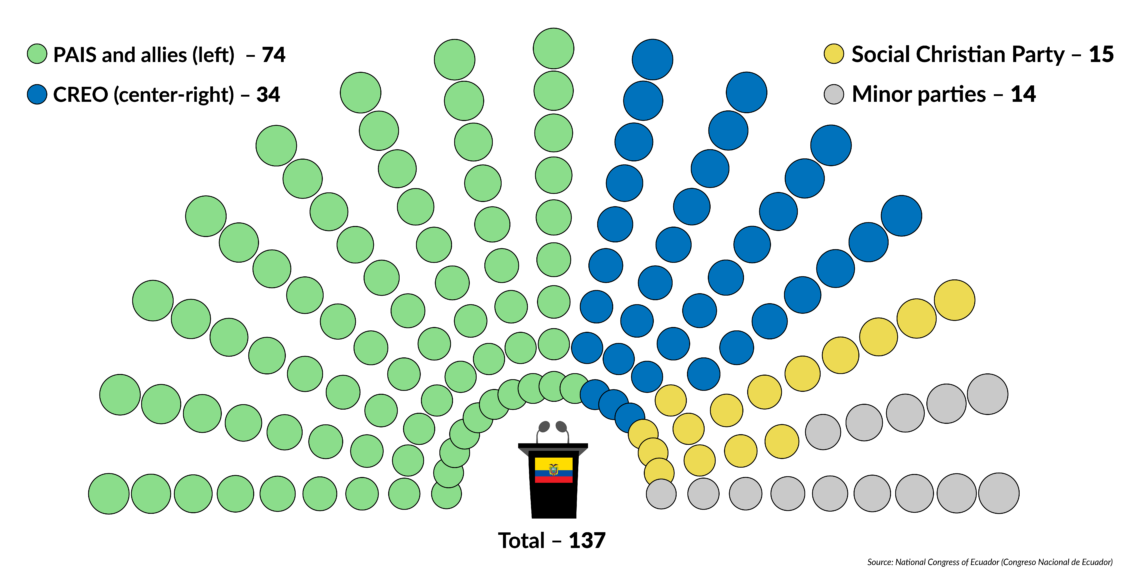

Mr. Moreno’s attempt to emancipate himself from Mr. Correa had immediate political consequences. The Alianza PAIS coalition fractured, costing the government its parliamentary majority. Just 46 leftist deputies in the National Assembly stood by Mr. Moreno, while 23 others remained loyal to Mr. Correa. In practice, this forced the president to rely on a motley collection of small parties to pass legislation. At times, he has even had to negotiate with Mr. Lasso’s center-right opposition, the Creating Opportunities (CREO) movement, which holds 34 seats.

Facts & figures

Ecuador's National Assembly

Deputies by party, 2017-2021

The core leftist constituency on which Mr. Correa built his political base is now split between those who want to strengthen institutions and the rule of law, like Mr. Moreno, and those focused on the inclusion and social justice issues that were at the heart of the Citizens’ Revolution. At the crux of the debate is language used in the new constitution of 2007, which holds that Ecuador is a country of rights, not necessarily a land of law (a play on the distinction in Spanish between El estado de derechos and El estado de derecho).

The debate acquired an extra edge because the Citizens’ Revolution had succeeded in cutting Ecuador’s poverty rate in half, before it began to rise again in 2016-2017 as plummeting oil prices cut government revenue.

As a social democrat, President Moreno should theoretically have the credentials to knit together Ecuador’s divided left. To do so, however, he must prevent the government’s efforts to pull the country back from the financial precipice from causing too much harm to the poor, who benefited from Mr. Correa’s social policies. In other words, the Moreno government cannot afford to be perceived as too “neoliberal.” If that were to occur, he might lose hold of both factions of Alianza PAIS.

President Moreno had clearly hoped that his call for a national dialogue would win him supporters from the anti-Correa movement and buy time for his fiscal policies to take effect. After initial praise, however, the domestic political debate has been slow to take hold, while the economy has remained sluggish. Over the past 18 months, Mr. Moreno has already gone through three economy ministers. Economic growth is estimated at 1.3 percent for 2018 and 1.6 percent this year, which is far too slow a pace to reduce poverty or significantly upgrade infrastructure.

Corruption card

In the absence of a thriving economy, President Moreno’s main hope for gaining popular support is his campaign against corruption. There have already been a few spectacular successes. Soon after the new government took office, Vice President Jorge Glas was suspended from office for his involvement in the Odebrecht scandal. In December 2017, he was sentenced to six years in prison for taking more than $13.5 million in bribes from the Brazilian conglomerate.

Mr. Correa is also feeling the heat. He is being investigated for alleged involvement in an abortive 2012 kidnapping of an opposition legislator. Faced with a July 2018 warrant for his arrest, he requested asylum in Belgium (his wife is a Belgian citizen) and called the allegations against him a political witch hunt.

President Moreno’s critics on the left are quick to accuse him of using the anti-corruption campaign as a smokescreen for his turn to neoliberal policies. However, his energetic pursuit of corrupt officials has won him support from private business and civil society organizations, which are more concerned about strengthening the country’s institutions. Bodies such as the Transitional Council on Citizen Participation and Social Control (CPCCS-T), which is part of the National Anti-Corruption Commission, have played an important role in creating a sense of transparency in the election of public officials, including the judiciary and the public controller’s office. Their continued success will be crucial to President Moreno’s efforts to woo the electorate.

One constituency that Mr. Correa never managed to win over was the indigenous communities of the Andean region. Here the conflict revolved around the incursions of international petroleum companies, which are trying to exploit oil deposits on the eastern slope of the Andes. Throughout his presidency, Mr. Correa backed the oil companies, despite his ballyhooed promise of changing the country’s energy matrix and “keeping the petroleum in the ground.” In addition, many of the contracts with Chinese companies, most of them effectively state-controlled, were suspected to have been finalized with the assistance of bribes to members of the Correa government and in violation of environmental protection laws.

Policy pivot

President Correa’s effort to get China involved in Ecuador’s development was touted as part of his broader foreign policy goal of ending U.S. regional hegemony, in part through participation in ALBA. Today, however, there is concern that China’s role as a major creditor has imposed a new form of dependence on Ecuador. A significant portion of these Chinese investments and loans is pegged to guaranteed deliveries of future petroleum output. Slumping oil prices make these loans less attractive for Ecuador than at the time of their inception. Currently, the Chinese credits cost nearly twice as much as typical loans from Western multilaterals or private lenders.

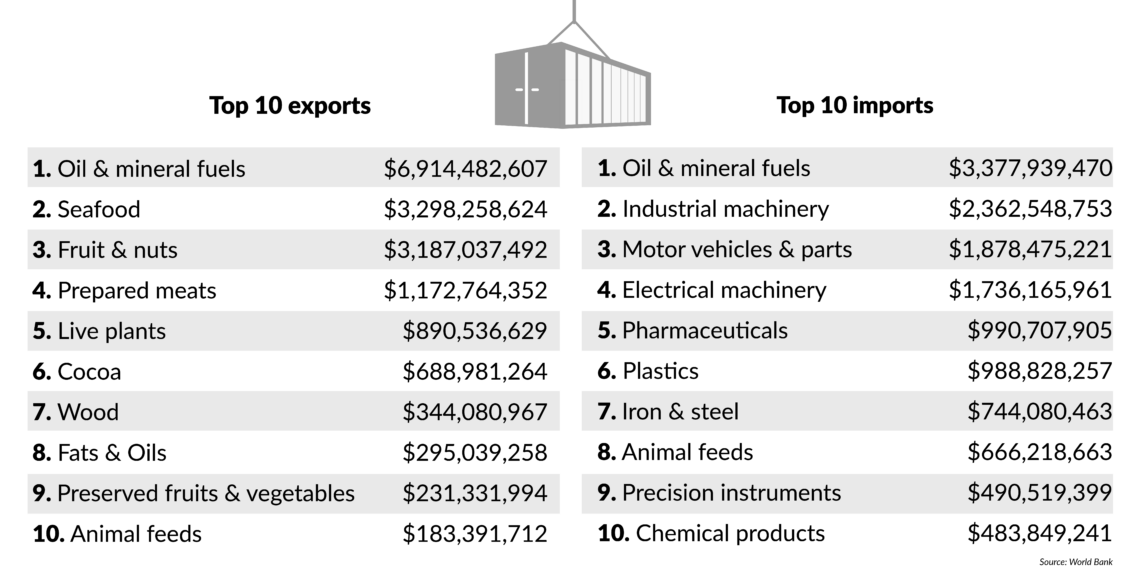

Facts & figures

Ecuador's foreign trade

The debate in Ecuador today is whether President Moreno’s efforts to pivot away from China and the “anti-imperialist” policies of the Correa era mark a return to the unforgiving dominance of the U.S. Mr. Correa’s followers see China as a benevolent partner and not a meddling hegemon. On the other side of the coin, the usurious rates of Chinese loans have led some to worry that Beijing’s aim is to make Ecuador, along with Venezuela, a captive member of the yuan zone.

A complicating factor is that Ecuador’s adoption of the U.S. dollar as its own currency is making its exports less competitive, especially to its closest neighbors and important trading partners, Colombia and Peru. As part of his pivot, President Moreno has made overtures to the members of the Pacific Alliance (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) to escape or at least weaken China’s grip.

Scenarios

President Moreno can certainly muddle through for the next few months. His fiscal caution, together with the prospect of outside financing from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, will save the country from default and complete paralysis. That, in turn, will encourage more activity from local stakeholders, including the private sector and the CPCCS-T.

These developments will make Ecuador more attractive to investors than it has been in decades. If exports can be sustained, even a small increase in investment could allow the Moreno government to sustain the minimum of social spending needed to fend off accusations that it is too neoliberal. The longer President Moreno can maintain this delicate balance, the more likely the economy is to stir from its lethargy.

The government’s most urgent task is to negotiate for cheaper financing of its foreign debt. With regional and local elections set for March 24, 2019, Mr. Moreno will also need to continue his assault on corrupt officials and promote transparency to win over voters disillusioned by the Correa experience. Given the fractured political scene, it is unclear how organized parties can help sustain the president’s agenda and stabilize the government. The more success Mr. Moreno has in stimulating the economy, the more inclined his colleagues will be to cooperate.

Under a less probable scenario, the economy will stagnate and the president will be forced to adopt a tougher fiscal approach. This would completely alienate the left and derail efforts to enlist the private sector, indigenous groups and civil society organizations through the National Dialogue. If Mr. Moreno swings too far to the right, Ecuador will become harder to govern. Unless the coming fiscal crisis is dealt with effectively, the country could even default on its debt.