Egypt’s El-Sisi faces hurdles

When he came to power, Egyptian President El-Sisi set his country on a relatively liberal path. After several years, he had to change tack to fight radical Islamism. To continue the progress he has made, El-Sisi will have to introduce reforms that could prove unpopular in Egypt.

In a nutshell

- President El-Sisi has made crucial economic changes

- He will need outside support for further reforms

- He is unlikely to receive this support from the West

This new series of GIS reports examines how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies and nations’ development prospects.

Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi does not fit the mold of a politically correct European leader. He has become a controversial figure, often reviled in the West. Yet he has made huge strides in Egypt, especially economically, pulling his country out of a deep hole and offering hope to many of its impoverished citizens.

In 2006, when he was attending the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, then-Brigadier General El-Sisi wrote a term paper entitled “Democracy in the Middle East.” Democracy, he concluded, would benefit the region but would need to be adapted to Islam because of the religious nature of the Middle East. “[I]t is not necessarily going to evolve upon a Western template,” he wrote. Instead, it “will have its own shape or form coupled with stronger religious ties.”

After assuming power in 2013 and being formally elected Egypt’s president in 2014, Mr. El-Sisi seemed to be leading the country toward a more democratic system. However, by 2018, political realities pushed Mr. El-Sisi in a more authoritarian direction, with a focus on curbing the influence of Islam.

Constitutional changes

One of Mr. El-Sisi’s first steps as Egyptian leader was to draft a new constitution, which was approved in a 2014 referendum. It established the separation of powers, as well as checks and balances between the executive and the legislative branches of government. The judiciary was to be completely independent. On the other hand, sharia remained the main source of legislation and the grand imam of the highly prestigious Al-Azhar Mosque maintained enormous influence.

The president was limited to two four-year terms in office, as in the United States. For the international community, it was a clear indication that Egypt’s new leader intended to establish a liberal regime – in Middle Eastern terms – after the revolutions which had first ousted its previous presidents, Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011) and Mohamed Morsi (2012-2013).

President El-Sisi took measure of the obstacles in his path and moved to amend the constitution to grant him more power.

Yet as his first term of office was winding down, President El-Sisi had taken measure of the obstacles in his path and moved to amend the constitution to grant him much greater powers. The changes extend the presidential term from four to six years and allow Mr. El-Sisi to run for a third term. In effect, he will remain in power until 2030.

The amendments reestablished an upper house of parliament, which had been abolished with the 2014 constitution. The new upper house will be called the Senate, and the president will be allowed to appoint 60 of its 180 members.

The amendments also empower the president to appoint his vice presidents, the president of the Supreme Constitutional Court and the attorney general. The powers of the State Council (the administrative court system), including the Supreme Administrative Court, were curtailed. The army, previously tasked with “protecting the nation and guaranteeing its security and integrity” now has the power to “safeguard the constitution and democracy, maintaining the foundations of the state and its civilian nature, the gains of the people, and the rights and freedoms of the individual.”

With these changes, fields traditionally attributed to the parliament, the judiciary and civil society are now in the hands of an institution not known for its respect for human rights. President El-Sisi is free to govern with minimal interference from the legislature or judiciary.

Building support

Like President Mubarak before him, Mr. El-Sisi relies on the army. Egypt’s armed forces play a powerful economic role, producing and exporting a wide range of military and civilian commodities, and dominating 30-40 percent of the economy. In some sectors it has a monopoly. It has tremendous privileges set down in the constitution: there is little control over its budget, which is not open for scrutiny. Yet the army enjoys extraordinary prestige. Seen as the symbol of the country’s unity, it is much-loved by the people who are proud of their soldiers. Successive surveys have shown that Egyptians believe it must play an important part in ruling the country.

Contrary to his predecessors, former Presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954-1970), Anwar Sadat (1970-1981) and Mubarak, President El-Sisi refrained from setting up his own political formation and instead implemented changes in the electoral system favoring the election of independent candidates who were his supporters. He has a stable majority of some 60 percent of the 596 members of the House of Representatives, the lower house of parliament.

Facts & figures

Faced with implementing reforms, quelling seeds of protest and fighting Islamic terror, he soon resorted to measures inconsistent with Western norms. Domestic criticism against the regime has been curbed. Parliament has passed regulations limiting freedom of assembly, the right to demonstrate and civil society activity. Egyptians have been arrested by the thousands with many, but not all, belonging to the banned Muslim Brotherhood. Potential opposition leaders have been targeted, as have journalists and human rights activists. Independent television channels and newspapers have been shut down.

President El-Sisi must have known that the West would look askance. Yet he believed that facing the consequences would be necessary if it meant preventing the potential instability that could stem from the people’s discontent as reforms led to price increases.

Introducing reforms

Nevertheless, he kept his promise to implement wide-ranging reforms that would ultimately bring sustainable development. He began with huge infrastructure projects and then turned to the International Monetary Fund to help him restructure the economy. The IMF gave him a loan of $12 billion, conditional on sweeping reforms. The president complied, gradually canceling most energy subsidies and floating the Egyptian pound – the exchange rate rose from about 8 Egyptian pounds to the U.S. dollar to a more realistic 18 per dollar. He introduced a value added tax and simplified the rules governing financial transactions, taxes and customs with a view to attracting foreign investments.

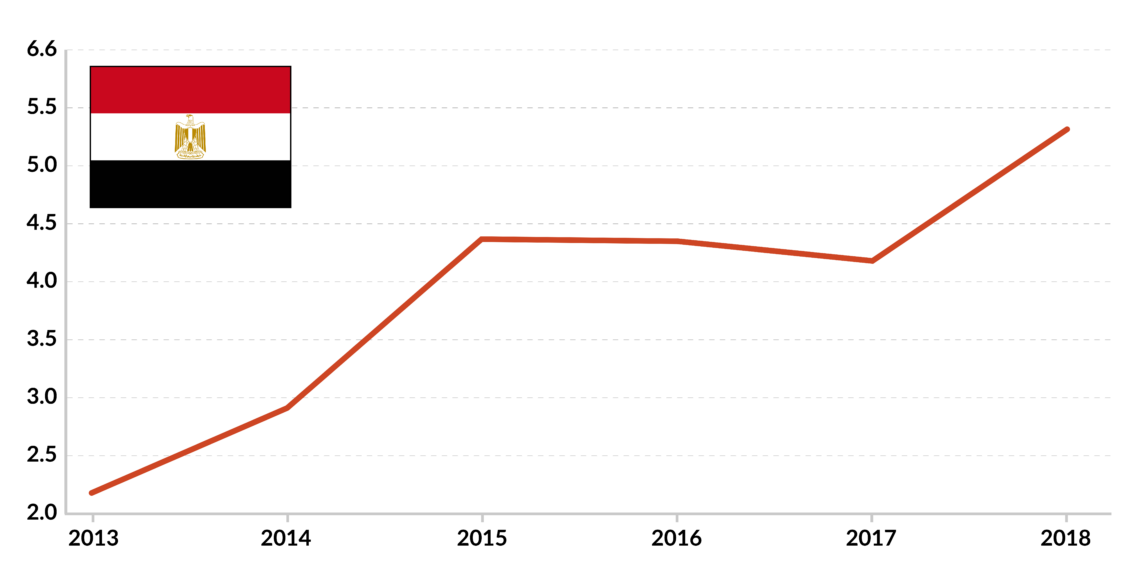

Within a year, Egypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) had grown by about 4 percent. Since then, growth has continued to steadily increase, and is now heading toward 6 percent. Prices, however, kept rising. Inflation reached 35 percent in 2017, though it fell to around 7 percent by the end of 2019. Poverty rose from 27.8 percent in 2015 to 32.5 percent in 2018, according to the state statistical agency.

Egyptians seemed to have had enough strife and instability, and understood the need for reforms, however painful.

It had been widely expected in the West that Egyptians would revolt against the regime, but their discontent did not lead to mass protests or to a significant political opposition movement. Egyptians seemed to have had enough strife and instability, and understood the need for reforms, however painful.

Yet sporadic demonstrations against President El-Sisi began in September 2019. For many pundits in the West, it was a sure sign that his era was coming to an end. Can they be right, or are they once again misinterpreting temporary setbacks in a Muslim country that has never known democracy?

Western bias

Much of Western media has been biased against President El-Sisi from the start and had shown itself unwilling to accept someone who had come from the ranks of the army like President Hosni Mubarak and who had ousted the democratically elected President Morsi. Western politicians shunned him as well. U.S. President Barack Obama showed his displeasure by suspending some of his country’s military aid to Egypt and turning a deaf ear to the new president’s request for assistance and help in securing investments.

Though the September demonstrations soon fizzled out, leading French newspaper Le Monde wrote that “the bonds between El-Sisi and his people are fraying.” In October 2019, the European Council on Foreign Relations issued a strongly worded comment in which it wrote, “The re-emergence of public protest should remind the European Union that [President El-Sisi’s] policies do not provide a basis for long-term stability. It is high time that Europe pressed for a course correction and called out repression.” On October 24, 2019, the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for a profound revision of the EU’s ties with Egypt, insisting that respect for human rights should be central to relations.

The resolution originally included a ban on weapons sales to Egypt, but that provision was removed, likely due to pressure from several interested parties. In 2017, 14 EU member states sold arms to Egypt. The country has consistently been an important purchaser of arms from Europe. In 2015 France signed weapons deals with Egypt worth more than $6 billion.

Facts & figures

Governance in Egypt

Egypt is a presidential republic divided into 27 governates. Its constitution was approved by referendum and ratified by then-interim President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi in 2014. The country has a mixed legal system based on Napoleonic law, Islamic law and vestiges of colonial-era laws. The Supreme Constitutional Court provides judicial review of the constitutionality of laws.

Executive branch

- The president is chief of state, while the prime minister is head of government. Cabinet ministers are nominated by the executive branch and approved by the House of Representatives

- Presidents are elected by absolute majority, in two rounds if needed, for a six-year term (eligible for three consecutive terms)

- Prime Ministers are appointed by the president and approved by the House of Representatives

Legislative branch

- Currently, the parliament is unicameral, and consists of the House of Representatives, which has 596 seats. Members serve five-year terms

- In an April 2019 referendum, voters approved amendments to the constitution, among which an upper house of parliament was restored. The Senate will have 180 seats, 60 of which will be taken by presidential appointees

Judicial branch

- The country’s highest court is the Supreme Constitutional Court, comprised of 11 judges

- The Court of Cassation is the highest appeals body for civil and criminal cases. It consists of 550 judges organized into circuits

- The Supreme Administrative Court is the highest of the administrative court system

President El-Sisi himself was taken by surprise by the September 2019 protests, because they came from an unexpected source: a little-known construction contractor who used to work with the army. Accused of corruption, President El-Sisi swore that the charges were lies trumped up by “political Islam” – meaning the Muslim Brotherhood – to cause internal strife. On Twitter, the president said that he was attuned to the suffering of the poor. Later, his government announced that it had returned 2 million Egyptians back onto food subsidy rolls after they had previously been cut in an effort to reduce waste and graft.

The protesters, mainly young people and students with no political affiliation, were forcibly dispersed and some 2,000 were arrested. Security measures were reinforced; several Cairo subway stations were closed. There does not seem to have been a political formation behind those protests. Muslim Brotherhood sleeper cells did take advantage of the events to incite to violence, with little success. In Qatar and Turkey, media affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood severely criticized the Egyptian regime.

In a country suffering from underdevelopment and overpopulation, and with no tradition of democracy, could the regime have taken less repressive steps? Would it have been feasible to first install a truly democratic regime and then launch the necessary reforms?

Next steps

Indicators show that Egypt’s economy has vastly improved. National debt, which had reached 100 percent of GDP in 2017, is now about 85 percent and continues to decrease. However, exports, which many expected to be the country’s main growth engine, have disappointed. Though the devaluation of the Egyptian pound boosted exports, from $21.7 billion in 2016 to nearly $30 billion in 2019, there are few prospects for further growth. Crude oil and gas exports still account for 34 percent of total exports. The industrial sector has not gained strength as hoped – its products have proven uncompetitive in the global market. Industry accounts for only 17 percent of Egypt’s GDP, and agriculture 13 percent.

Now that the necessary structural reforms have run their course, President El-Sisi must tackle core social issues and find new sources of revenue.

Now that the necessary structural reforms have run their course, President El-Sisi must tackle core social issues and find new sources of revenue, pushing for more foreign investment and technological advancement. Finance Minister Mohamed Maait announced in October 2019 that he was conducting talks with the IMF on a new loan package starting March 2020. The next reforms will need to include tackling challenges like modernizing the outdated education system, instituting changes in religious discourse and making room for critical thought.

In Egypt, as in all Arab states, sharia is still the main source of legislation. The Islamic establishment resists any change. Most attempts to adjust to the needs of a rapidly evolving modern world have failed. Liberal thinkers in the Arab world agree that the only way to develop true democracy is to separate religion and state. At this stage, that seems unlikely to occur. It is crucial to remember that after the Arab Spring toppled dictatorial regimes in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, Islamist parties won elections in all three countries. The people of the region are still deeply attached to their religion, as Mr. El-Sisi wrote in his essay. The religious establishment derives its strength from that attachment.

The president has not given up. He has instructed the education ministry to remove the most extreme narratives from elementary schools’ textbooks, asking Al-Azhar to help and to move toward a revision in Islam. He was met by a stony rebuttal from the mosque’s grand imam, who stated that sharia was perfect and suitable for all situations and times. The two sides have reached a stalemate which will have to be broken at some point.

Today, with the full powers granted him by the constitutional amendments, Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi is expected to rule Egypt until 2030. He knows that it will be up to him to consolidate his reforms and address the roots of his country’s problems. It is a formidable challenge that no Arab country has yet met.

Scenarios

The coming years will bring their share of unrest in Egypt. The president will have to continue battling the religious establishment, circumventing traditions and long-entrenched customs. Winning that battle will require thoroughly modernizing the educational system, moving away from rote learning and toward critical thinking. It will not be easy, and the president will need the support of the army to maintain stability. Its allegiance is not necessarily a given. President Mubarak was toppled by the leaders of the army, who had concluded that it was the only way to assuage popular anger.

In a worst-case scenario, discontent from the poorer classes will trigger a new upsurge of protests, joined by the Muslim Brotherhood and conservative religious circles dissatisfied by the president’s policies. The army would have to intervene to quell the ensuing violence. The regime might have to restore large-scale subsidies to appease the masses. This would spell the end of the reforms.

A more plausible scenario would be for the army to maintain the peace, enabling the president to proceed with his modernization projects. Success is not guaranteed and will take time, with Egypt suspended between hope and despair for many years. To succeed, Mr. El-Sisi will need outside support. If the Western countries took a closer look at the reality on the ground and showed a modicum of understanding for a regime striving to change things in Egypt, it could, with a bit of luck, become a beacon of hope for the whole troubled region.