President Bukele’s play for power

El Salvador’s President Bukele has trampled over democratic norms, but he has also drastically reduced violence and brought stability to the troubled Central American country. Now the Biden administration needs to decide how to deal with him.

In a nutshell

- El Salvador's President is eliminating checks on his power

- Nayib Bukele enjoys both legislative and popular backing

- U.S.-El Salvador relations could suffer going forward

Within hours of taking power on May 1, 2021, El Salvador’s newly seated legislative assembly, dominated by the party of President Nayib Bukele, dismissed five members of the Constitutional Court and the attorney general. It then replaced the justices with presidential loyalists, effectively handing the president control of the country’s judiciary.

These moves mark the latest in the president’s attempts to remove institutional constraints to his rule and demonstrate a worrying erosion of the country’s separation of powers. While President Bukele’s consolidation of authority may bring a measure of short-term stability for the country, it will also test United States-El Salvador relations and could endanger foreign economic relief.

Reshaping politics

President Bukele, formerly an advertising executive and mayor of San Salvador, has rapidly altered the forces of political power since coming to office in 2019. The president’s election from the New Ideas (Nuevas Ideas) party – a vehicle for his political ambitions more than a program-based organization – broke the post-civil war duopoly of the right-wing ARENA (Alianza Republicana Nacional) and the leftist FMLN (Frente Farabundo Marti para la Liberacion Nacional). It made him the first party outsider to win a majority of the vote since re-democratization. The two traditional parties had been discredited after failing for decades to effectively combat corruption or the gang violence that has frequently made El Salvador one of the deadliest places in the world. President Bukele is acting on a popular mandate to break with the status quo.

The president has repeatedly shown his willingness to violate democratic norms to get his way. For instance, in a much-publicized episode in February 2020, he ordered the military to occupy the Legislative Palace to intimidate opposition lawmakers into approving a loan for the country’s security forces. He then threatened to have opposition legislators forcibly removed from the building.

The president’s party won a supermajority, meaning the government will be able to rule virtually unopposed.

Then, in March and April 2020, when the Supreme Court issued a series of decisions ruling that it was illegal for police to arrest people who defied a pandemic lockdown, President Bukele responded by making public statements defying the court and publicly ordering officers to ignore the ruling. Adding a populist twist, one week before the February 2021 legislative elections, the president, first lady and minister of education began delivering free computers to students in public schools across the country.

Party power shift

The president’s party made significant gains. New Ideas won 56 of 84 seats in the unicameral legislature, giving the president a supermajority, while the traditional parties of ARENA and the FMLN earned a scant 14 and four seats, respectively. This dramatic shift in party power represents a transformation of the Salvadoran political landscape and means that the government will be able to rule virtually unopposed, including through the removal of “unfriendly” members of the judiciary.

There was little pretense of following constitutional procedures in the legislature’s dismissal of the high court magistrates. The attorney general, Raul Melara, had opened investigations into allegations of corruption in the Bukele administration regarding Covid-related contracts and unauthorized covert negotiations with gangs. By installing a more friendly attorney general, Bukele has killed those ongoing investigations and guaranteed that future such dealings will not face prosecution.

President Bukele has rapidly altered the forces of political power since coming to office in 2019.

Building on this, on May 5, the legislature approved a bill that provides immunity for health sector officials from administrative and legal complaints in relation to Covid-19. The legislation should aid government allies such as the minister of health, who has faced corruption allegations concerning the pandemic response. Yet while many foreign observers condemned this legislation as a perceived abuse of power, domestic criticisms against President Bukele’s actions have been more tempered.

Strong mandate

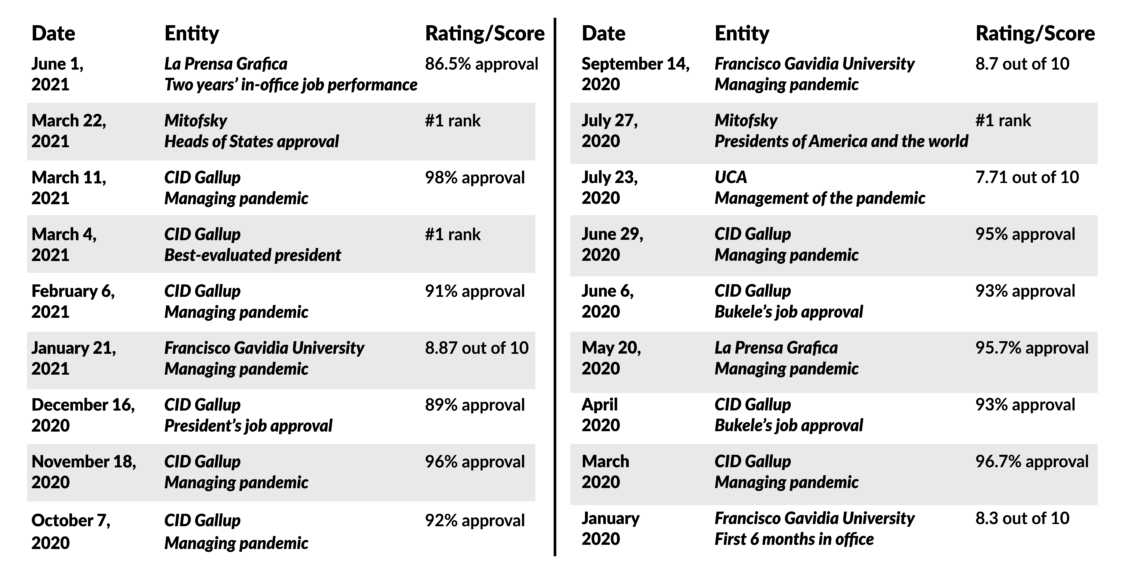

New Ideas’ electoral gains and Mr. Bukele’s successful power grab reflect the president’s high standing among Salvadorans. In fact, President Bukele enjoys some of the highest approval ratings of any Salvadoran president in the country’s democratic history and any elected president in the Americas. Since coming into office, every public opinion poll, including those conducted by international firms, has found support for him exceeds 75 percent. Many of them have even given him numbers in the 90 percent range. These figures are consistent across regions, age groups and gender. So, while other Latin American leaders who threaten democracy and the rule of law face pushback and opprobrium from voters, President Bukele has used his high approval ratings to justify his actions. Many see them as a necessary antidote to politics as usual.

Facts & figures

The president has received especially high marks for his handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. A CID Gallup survey conducted in March 2021 showed that a remarkable 98 percent of Salvadorans approved of Mr. Bukele’s management of Covid-19. He introduced one of the world’s most stringent lockdowns beginning in March 2020, shutting down public transport, schools and stores, and quarantining citizens to their houses. He then deployed the army at checkpoints to enforce the lockdown measures. However, to mitigate the economic shock of the three-month quarantine, the government introduced a series of supporting measures, including a cash transfer of $300 aimed at informal sector workers, a three-month freeze on utility bills and loan payments and the distribution of some 2.7 million food baskets to needy households.

The decline of violence has also greatly aided the president. The homicide rate in the country has fallen from 47 per 100,000 when he came to power in June 2019 to somewhere around 20 per 100,000 by early 2021. Investigative website El Faro and others have suggested that the dramatic decline in violence is the result of a truce the government has brokered with the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 gangs. In September 2020, El Faro claimed that President Bukele had secretly negotiated a deal with MS-13. The gang pledged to both reduce the number of murders it committed and support New Ideas during the elections in exchange for more flexible prison conditions for its members. The president denied these allegations.

In short, the president’s mandate is strong, and barring economic disaster or a worsening of security issues, he is poised to remain popular.

International fallout

The U.S. is trying to walk a fine line with El Salvador: it wants to preserve the country as an ally as it competes with China for Latin American countries’ attention, while promoting anti-corruption and pro-democracy values it thinks may help stem the tide of Salvadoran migrants to the U.S. It has been careful in dealing with President Bukele. Before the February elections, members of the Biden administration refused to host the Salvadoran president during an unannounced visit to Washington, D.C., for fear that it would be seen as an endorsement.

Still, many in Washington were quick to condemn the dismissal of judges. Vice President Kamala Harris denounced the removals, and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke with the Salvadoran president by phone to express the U.S. government’s concern. Further, Secretary Blinken warned President Bukele that U.S. economic aid is inseparable from the Bukele government’s commitment to democratic practices.

The moves could jeopardize efforts by the Bukele government to secure financing from international lenders.

Investors demonstrated their own anxieties about Mr. Bukele’s plans by selling heavy volumes of Salvadoran bonds after the dismissals. The dollar bonds suffered the biggest one-day decline since the onset of the pandemic. This suggests that unless President Bukele can persuade the private sector and foreign investors that he is committed to the rule of law, it will become more expensive for his government to borrow money. In a worst-case scenario, the government might have to enter a debt restructuring process if investors lose confidence in the country.

The removals could also jeopardize efforts by the Bukele government to secure financing from international multilateral lenders, which may be necessary to ensure El Salvador’s economic recovery from Covid-19. El Salvador is in the middle of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $1 billion program to cover a budget shortfall, following a prior $389 million deal. However, external opposition may be growing to these talks. U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Menendez and Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy said the Biden administration should tell the IMF that U.S. support for funding depends on respect for democracy, judicial independence, and the rule of law.

Scenarios

Despite criticism from the U.S., the Organization of American States and international human rights groups, there is little sign that President Bukele will abruptly reverse his authoritarian push. New Ideas’ legislative electoral success and control over the judiciary allow the president to consolidate executive authority, and it is almost certain that he will use his popularity and powers to continue steamrolling checks and balances.

Domestic politics

The political reality is that Mr. Bukele has enough votes to pass any law, budget, or constitutional amendment he wants. There are some institutional rules and checks on executive power that should prevent him or his party from totally overhauling El Salvador’s democracy in a short time frame. However, the weight of the president’s popular mandate and legislative support will help him bend or break many constraints. The president’s legislative majority should allow him to pursue changes to the constitution, including the potential removal of restrictions on consecutive presidential reelection. Moreover, he should be able to neutralize opposition in government institutions.

It is a near certainty that civil society will suffer. As in other Central American countries, a crackdown against domestic political opponents is practically inevitable. The situation is especially dire for media outlets and civil society groups that are critical of the government. Pressure, threats and harassment are likely to increase. At the same time, like many presidents only weakly committed to democracy, Mr. Bukele will build a supportive civil society and media ecosystem to neutralize his opposition.

Despite the dire long-term forecast, by far the most likely scenario for El Salvador in the coming year is one of relative stability and prosperity. From an economic and security perspective, things are likely to improve for the average citizen. Having a single individual in charge and able to govern with both legislative and popular support bodes well for economic growth. Meanwhile, the president’s policies – truce or no truce – have significantly improved El Salvador’s security situation. Nonetheless, in the long term, the outlook is murkier: having politicized prosecutors and an unfairly stacked judicial branch will benefit organized crime. And gang truces are difficult to maintain over an extended period.

Foreign politics

Internationally, President Bukele’s first and best choice is to curry favor with the U.S. Not only is the Salvadoran economy dollarized, but remittances from the U.S. make up a large share of the country’s economy, and there are significant social and cultural ties between Salvadorans in the U.S. and their home country. This may imply tempering antidemocratic rhetoric or constrain even less defensible antidemocratic actions.

The most likely response from the U.S. is a carrot-and-stick approach to encourage the rule of law protections and cooperation on security and migration matters. Like attempts to impose sanctions, purely punitive action will probably have a more substantial impact on ordinary citizens than on the Salvadoran government. For example, using immigration rules as leverage is possible, but this would be more harmful to the two million Salvadoran migrants in the U.S. than to the Bukele administration. Similarly, blocking IMF action would put significant financial pressure on the president but would also lead to greater suffering and possibly push Mr. Bukele to seek out China for financial support. Despite the rhetoric, this seems unlikely.

Another plausible scenario is one where ongoing friction with the U.S. causes President Bukele to pivot toward China. El Salvador formally cut diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 2018 and increased its ties with China. After taking power, President Bukele met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, and agreed to a large infrastructure deal. In this scenario, Mr. Bukele could try to play the Chinese against the U.S. to see how much the Biden administration is willing to overlook to ensure it remains El Salvador’s partner of choice.