El Salvador’s new president faces an uphill struggle

In June 2019, Nayib Bukele will take office as the next president of El Salvador. A fresh face from a small party, Mr. Bukele wants to root out corruption. For its part, the U.S. wants him to tackle migration. With a sluggish economy, the new president will have to solve the problems that are chasing Salvadorans from their country.

In a nutshell

- Nayib Bukele’s election as president is a rebuke of El Salvador’s main parties

- He promises to root out corruption, but won’t have much support in the legislature

- The U.S. wants the new president to tackle migration, but he will need aid to be able to do so

On June 1, 2019 Nayib Bukele, a former mayor and businessman, will enter office as the new president of El Salvador. Mr. Bukele’s election in February was remarkable for several reasons. Most importantly, it came in the first round, with a clear majority: 54 percent of the vote. Moreover, he ran as the candidate from a small, conservative party, the Grand Alliance for National Unity (known by its Spanish acronym, GANA). Taken together, these factors made his election a sharp rebuke of the two main parties, the FMLN on the left and ARENA on the right, which had run the country since its civil war ended in 1992.

Mr. Bukele’s campaign used social media to an unprecedented extent for Central America. He focused on the corruption of his predecessors and their parties. El Salvador’s two most recent presidents, Antonio Saca (2004-2009) of ARENA, and Mauricio Funes (2009-2014) of the FMLN, are both accused of embezzling more than $300 million. Combined, the over $650 million they are suspected of stealing is an astounding chunk of money, especially viewed against the country’s 2017 gross domestic product (GDP) of $24.8 billion.

Mr. Saca is serving a 10-year prison sentence for his crimes, while Mr. Funes has taken refuge in Nicaragua. Mr. Saca’s wife, Ana Ligia de Saca, the former first lady, struck a deal with the country’s attorney general whereby she confessed to laundering $17 million from the presidential office’s accounts. She will complete three years of social work rather than serve time in jail.

Policy questions

President-elect Bukele was the mayor of El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador, from 2015 to 2018. He was a member of the FMLN until 2017, when he was expelled for his frequent criticism of party leadership. During the presidential campaign, he called for an end to the two dominant parties’ stranglehold on power. He offered few hints about which policies he would follow, except that he would ask the United Nations to create a commission to investigate corruption, similar to the one that until recently had been operating in Guatemala.

We have few clues as to how Mr. Bukele intends to govern.

Mr. Bukele ran under the GANA banner because his own newly established party, New Ideas (Nuevas Ideas) was not organized in time to register for the election. GANA and another small party allied with the president-elect hold 11 seats in the Legislative Assembly. ARENA has 37 and FMLN has 23, while smaller parties occupy the remaining 13 seats. Even in the likely event that many FMLN legislators choose to work with Mr. Bukele, his allies will still make up a minority in the legislature. He has not yet revealed whom he is considering for his cabinet, so we have few clues as to how he intends to govern.

Facts & figures

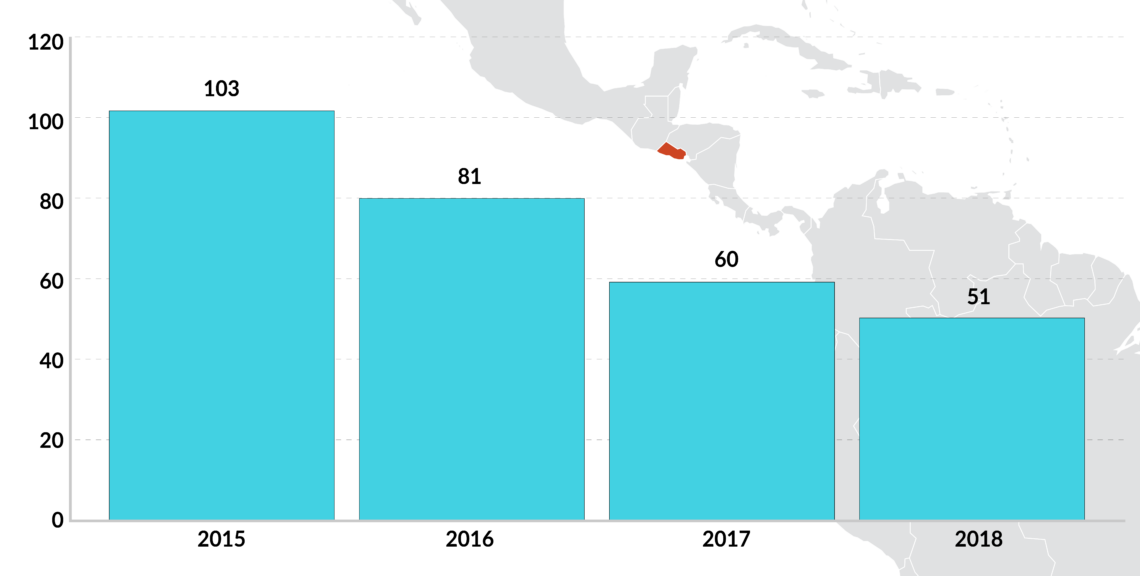

Declining homicide

Murder rate in El Salvador, per 100,000 inhabitants

Since the election, Mr. Bukele has visited both Mexico and the United States. During his tour, he promised to cut off relations with the authoritarian regimes in Venezuela and Nicaragua. He also made clear that aside from corruption, he recognized the country’s two other main problems. The first of these is violent crime, especially the activities of organized gangs known as maras. The second is the sluggish economy – Mr. Bukele will try to find ways to stimulate job growth. Addressing both issues would reduce pressure on Salvadorans to emigrate and the president-elect is counting on more aid from the U.S. to help achieve his goals.

The U.S. pulling back

However, President Donald Trump has threatened to cut off all aid to El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala – the three Central American countries sending most of the migrants to the U.S. That move would make it much harder to reduce the flow of migrants. There is evidence that the violence prevention program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) helped significantly bring down El Salvador’s homicide rate. U.S. government data show that the murder rate in San Salvador, for example, has fallen in each of the last three years. In the municipality of Zacatecoluca, which has an active USAID program, homicides dropped by more than 66 percent between 2015 and 2017.

Facts & figures

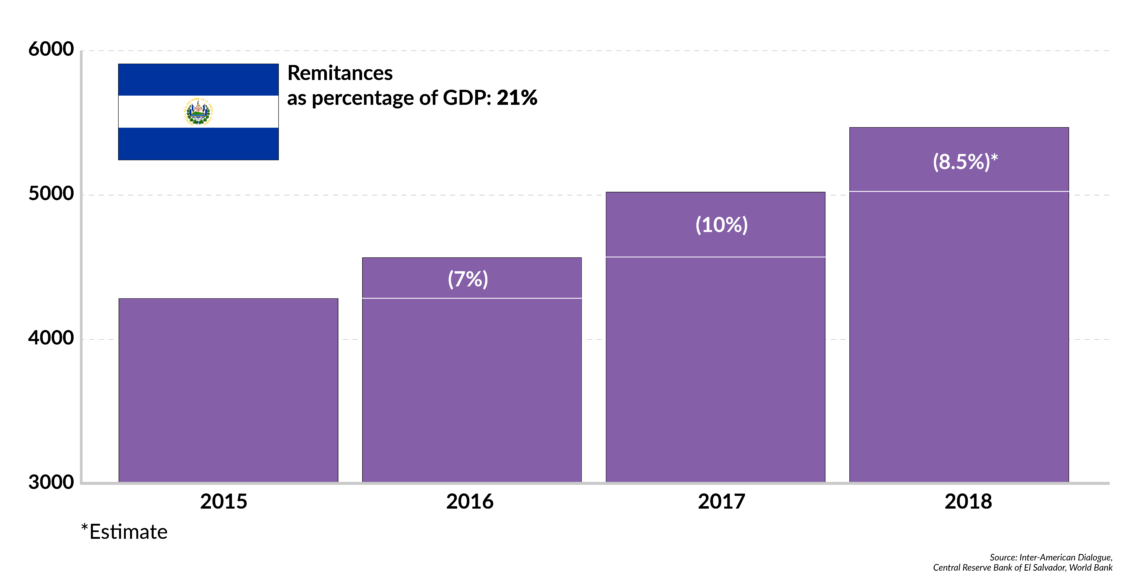

Remittances to El Salvador

$ millions (% growth year-on-year)

Without U.S. aid to stimulate the economy and to professionalize the police force, Mr. Bukele will be fighting an uphill battle. The economy has sputtered for over a decade. Last year, GDP growth was a disappointing 1.9 percent, despite the tremendous efforts of the Salvadorans in the U.S. who send remittances to their families back home. About one-fifth of El Salvador’s population lives in the U.S. The money this contingent sent back to the country amounted to an extraordinary 21 percent of its GDP in 2018. Fortunately for President-elect Bukele, those remittances show no signs of shrinking.