Mexico’s oil sector reforms face a challenge

Six years ago, Mexico began the process of reforming its oil and gas sector, opening it up to private investment and ending the state’s monopoly. The election of President Lopez Obrador has changed all that. Mexico is heading back toward resource nationalism but stands to lose out in the ultra-competitive global oil market.

In a nutshell

- Mexico’s new president has begun rolling back oil- and gas-sector reforms

- The reforms were badly needed and had attracted investment

- President Obrador’s moves could hinder development and hold Mexico back

Just six years ago, Mexico embarked on an ambitious economic reform program under the leadership of its center-left president at the time, Enrique Pena Nieto, who had come to power in 2012. The reforms were a major milestone, breaking with Mexico’s long-established precedent of reserving a dominant role for the state in the oil and gas sector. In 1938, Mexico was one of the first countries to nationalize its oil industry, and up until 2013, it was one of the few countries in the world and the only country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that remained closed to private international investment in its upstream oil and gas sector.

The current president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who was elected last July, seems to be gradually reversing the opening of Mexico’s hydrocarbons sector. The moves are no surprise. Mr. Obrador did not hide his resentment of the reforms prior to the elections. In Latin America in general and Mexico in particular, resource nationalism and the belief that the state should play a big role in the oil sector remain deeply rooted.

However, it is difficult to see how the policies that shaped government-investor relations over the past century in many oil-producing countries can succeed today. The oil market has drastically changed in recent years. Competition among oil producers for market share and international capital is becoming increasingly fierce, while calls for phasing out fossil fuels are intensifying.

Facts & figures

Mexico oil market

- Mexico is the world’s 11th-largest oil producer (BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2018)

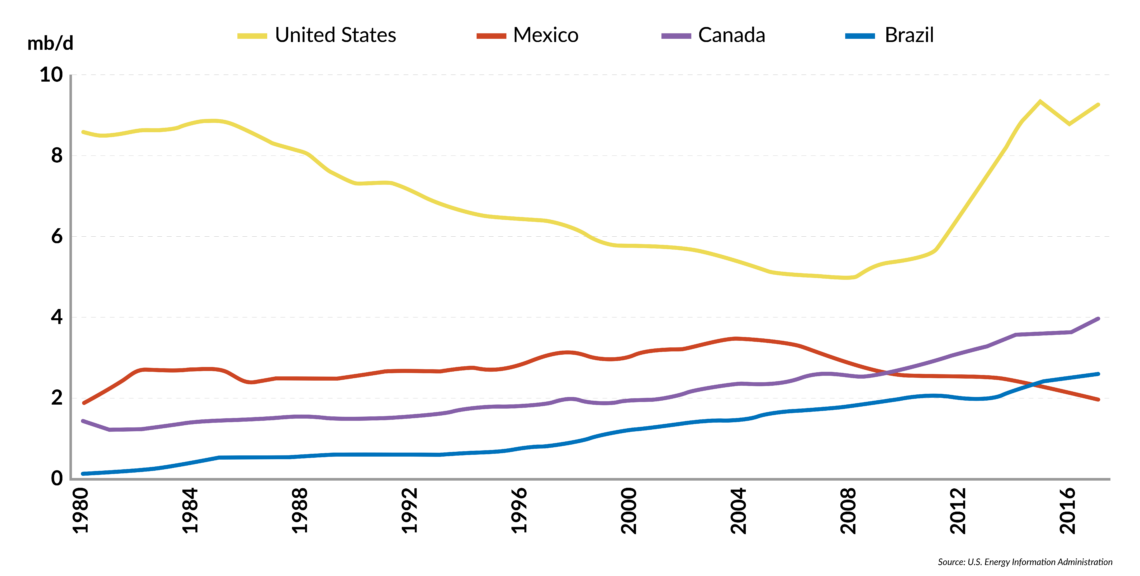

- Mexico’s oil production peaked in 2004 at 3.8 mb/d and has been declining at an average of 4% per year (EIA, 2018)

- In 1998, Mexico implemented oil production cuts in solidarity with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to stop a decline in oil prices. Nearly 20 years later, it announced a similar move, joining the OPEC+ deal. This was largely achieved through the natural decline in its production

- Between 2014 and 2018, Mexico awarded about 107 oil and gas exploration and production contracts, securing $305 million in income to the Mexican state (CNH, 2018)

- The country’s regulator, CNH, has approved investment plans for exploration and development contracts amounting to $20.571 billion. Of this total, 17% is to be spent in 2015-2018, 43% in 2019-2024 and the rest through 2041 (CNH, 2018)

- According to Moody’s, Pemex’s credit rating is affected by high liquidity risk, a heavy tax burden and resulting negative free cash flow, high financial leverage and low interest coverage, and challenges related to crude production and reserve replacement

Reforms

As part of a wider economic and social reform program, Mexico changed its constitution in 2013 to end the 75-year monopoly of the state oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), and foster competition in the country’s oil and gas sector.

Prior to the reforms, Pemex served two primary state functions: employment and revenue generation.

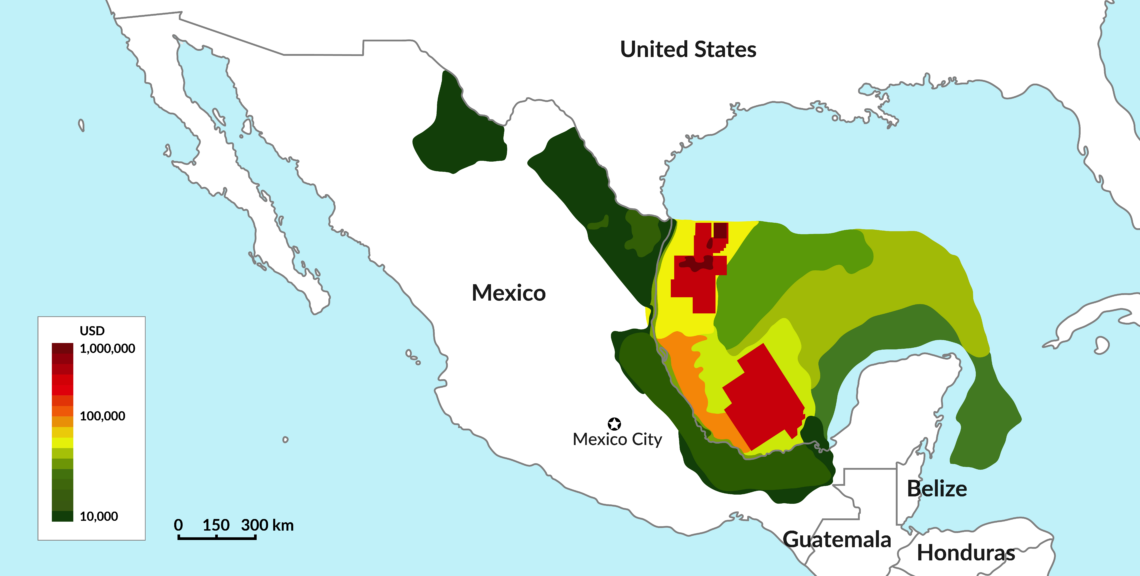

Pemex’s operations have mostly been limited to the country’s lowest hanging fruit, such as onshore and shallow-water projects, though many have passed their heydays and require significant capital injections to slow production declines. By itself, Pemex lacks the financial and technical capabilities to undertake such investments and to explore more challenging resources, such as those found in deepwater and shale basins.

Like many other national oil companies, Pemex is not solely focused on commercial operations. Prior to the reforms, Pemex served two primary state functions: employment and revenue generation. Partly because of these goals, Pemex had become uncompetitive, with financially unsustainable employment practices and pension liabilities. The state oil firm is unable to explore the country’s more challenging but potentially more lucrative resources because of inadequate investment in human capital and modern technologies.

There is a sharp contrast in the amount of activity between the U.S. and Mexican portions of the Gulf of Mexico, even though the geology is basically the same. On the Mexican side, far fewer petroleum projects are underway, and they are largely confined to shallow waters. On the American side, thousands of private companies keep pushing the boundaries of technology to explore new depths, thanks to competitive pressures and a supportive policy environment.

Facts & figures

Mexico lagging

Crude oil production, 1980-2017

According to official documents, the previous Mexican government hoped that the 2013 reforms would allow the country “to produce more hydrocarbons at lower cost, allowing private companies to complement Pemex’s investment through contracts for oil and gas exploration and extraction; and to achieve better results through competition in refining, transportation and storage.” The newly introduced competitive market structure would not only bring additional investment and maintain a sufficient stream of government revenue from the sector, it would also help Pemex improve operational efficiency.

Strong contender

International investors – big and small companies alike – were initially cautious but soon gave in to the temptation. The Nieto government’s initiatives created significant momentum. For instance, Mexico embarked on an aggressive licensing program to allocate generous oil and gas blocks and announced several rounds to appeal to a wide range of investors with different activity portfolios, risk appetites and technical abilities. Four calls for bids were held every year, targeting different opportunities (including shallow water, deepwater and onshore) with a total of three rounds between 2014 and 2018, each covering four bids per round.

Mexico’s relatively immature basins offer the potential for large discoveries, especially offshore. In the Gulf of Mexico, it is estimated that the country offers similar volumetric potential to the U.S., though it is almost completely unexplored. This potential has created intense competition that the Mexican government had successfully been exploiting. It was on the right path to attract investment that might have otherwise been channeled toward opportunities elsewhere in the region, especially in the U.S.

Discontent

That hope currently seems to be in danger. From the beginning, there was fierce opposition to the reforms. Many detractors equated them to selling and privatizing the country’s crown jewel: Pemex. Protesters took to the streets under the leadership of Mr. Obrador. After his election, the president was quoted as referring to what he perceived as the glory days of Mexico’s oil and gas industry in 1938, when the industry was nationalized.

President Obrador is keen on demonstrating that the reforms were a mistake.

After winning the elections, Mr. Obrador made several decisions that alarmed international investors. Chief among them was to halt the bid rounds for three years – a period he described as a “truce.” Although he tried to reassure existing investors that he was not going to cancel their contracts, he demanded that those contracts translate into higher production. Investors who hold exploration licenses, however, are unlikely to deliver.

President Obrador is keen on demonstrating that the reforms were a mistake, using the continuous decline production to support his claims. On the face of it, the reforms did not make any difference to Mexico’s production, which has continued to decline. This is because not enough time has passed since the contracts were awarded for the investments to be converted into production.

Conventional oil projects have long lead times between the initial investment and production being brought on stream, taking many years or even decades. Today’s conventional oil production is the result of exploration carried out at the turn of the century and investment decisions made years ago. The average person in the street, however, is unlikely to be familiar with this aspect of oil operations and would feel cheated, especially since production has been rising in neighboring countries.

Companies are partly to blame for the frustration. After making a discovery, they frequently trumpet its potential long before a full appraisal can give a more realistic picture of how much of the discovered resources can be extracted and by when. With such announcements, companies typically target the financial community but forget about the heightened expectations they arouse in the host country’s population, setting the stage for tension if those expectations are not met. The risk is much higher in a country like Mexico, which entered the new oil era with so much hesitation.

Broader perspective

Not respecting existing contracts, especially in an OECD country, can reduce investors’ confidence in government policies and commitments. What President Obrador’s government might do is revise the terms offered to future investors to secure tighter control and a bigger share for the state in oil and gas activities. Any benefit resulting from such a strategy would, however, be very limited. Mexico needs to consider that today’s oil markets are a far cry from what they were in the last century. If President Obrador is after investment, as he recently announced, then his policy is unlikely to secure it, especially with current oil prices and market uncertainties. Nor can Pemex deliver on its own.

Mexico could face the risk that a significant portion of its oil and gas resources may never be exploited.

Around the world, oil producers are fiercely competing for market share and international capital. In the Americas, Mexico’s closest competitor, the U.S., is challenging mighty producers like Russia and Saudi Arabia with reserves and production that dwarf Mexico’s. Despite the various problems that have engulfed its oil industry, Brazil is still a bigger producer, with an output of 2.6 million barrels a day (mb/d) in 2017 compared to Mexico’s 1.9 mb/d. Brazil has recently implemented investment-friendly reforms to boost its petroleum industry.

One should not count out Venezuela, either. The holder of the world’s largest oil reserves could make a comeback at some point, if it enacts the right policies. There are also new kids on the block, such as Guyana, which in the past few years has announced major discoveries that now await production. Outside the region, the picture is no less competitive.

On the demand side, the situation is more concerning, with some international organizations predicting that oil demand will peak at the end of the coming decade. In their dedication to fight climate change, more governments are calling for drastic reductions in oil consumption. Such trends put downward pressure on oil prices, making investment less attractive and causing further difficulties for debt-burdened companies like Pemex. Given the global nature of the industry, competition for international capital is also expected to intensify.

All in all, without a more explicit focus on accelerating investment and creating the right environment for attracting capital, Mexico will face the growing risk that a significant portion of its oil and gas resources may never be exploited.