Europe’s newest forum: Space for dialogue or photo opportunity?

The European Political Community will need momentum to bring concrete results for member states.

In a nutshell

- Big-tent philosophy can facilitate pan-European exchanges

- Informal structure makes it harder to realize tangible benefits

- Leadership of Paris, Berlin will be key to its success

With the European Political Community, a new intergovernmental grouping of 44 countries joined the continent’s crowded diplomatic scene in October, in a show of solidarity after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Its name, suggested by French President Emmanuel Macron, evokes the early days of the European Union. But will it be a step toward EU membership for Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and the Western Balkans? A framework for dialogue with the United Kingdom and other external states? Or a fleeting photo opportunity with little impact on the future of Europe?

Pragmatic approach

The EU’s bold decision in June to make Ukraine and Moldova candidates for EU membership – and a similar, more cautious pledge to Georgia – solved certain problems but created another. It acknowledged their EU membership aspirations, signaled unity amid Russia’s war in Ukraine and rebuffed Moscow’s claims that they fall under its sphere of influence. But membership for these states remains years, if not decades, away. How would the EU avoid disappointing these war-torn countries while they linger in Brussels’ waiting room?

President Macron has argued that the EU needs a new way to engage with other European states besides its faltering Neighborhood Policy and enlargement process. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has insisted that the EU must streamline its decision-making before expanding; otherwise, a body with up to 36 members would be dysfunctional.

The yearlong “Conference on the Future of Europe,” sponsored by France, failed to devise solutions. Mr. Macron’s proposed constitutional convention to rewrite the EU’s founding treaties did not materialize, with Europe gripped by war, supply shocks and inflation.

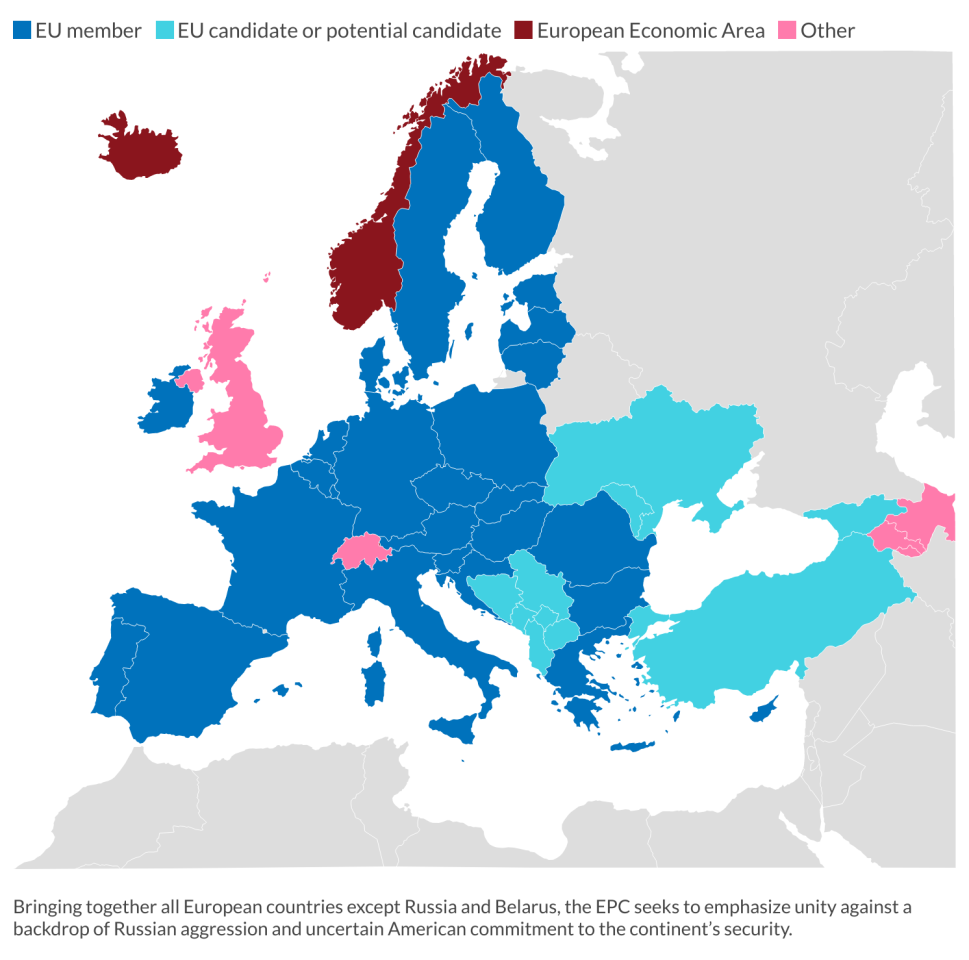

Instead, adapting an earlier French model, President Macron presented the EPC as a new structure, embracing all European countries except Russia and Belarus. This would deliver a message of unity, he claimed, against a backdrop of Russian aggression and a precarious American commitment to European security.

The informal structure can be appealing, but it is unlikely to satisfy fragile democracies looking for tangible support.

For EU candidates, it would be a bridge to membership; for other European states, it would reinforce diplomatic, political, and economic ties. The UK’s (initially hesitant) participation would be a significant first step toward post-Brexit cooperation. Mr. Macron expected the EPC to offer not only dialogue but also projects with tangible benefits, in areas like security and energy.

The EPC’s inaugural summit, organized by the Czech EU Council presidency, met in Prague on October 6, with 44 countries attending. These included 27 EU members, 10 EU candidates and potential candidates (including Turkey), three European Economic Area states (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway), Switzerland, Armenia, Azerbaijan and the UK. The presidents of the EU Commission and Council were also present, while Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy addressed the summit from Kyiv.

Roundtables focused on peace and security, climate change and energy, migration and the economy. On the summit’s sidelines, Armenia and Azerbaijan – whose forces recently clashed again, following a 2020 war over disputed territories – approved an EU civilian mission posted on the Armenian side of their border.

The Prague summit’s pragmatic approach was widely welcomed. Further meetings were scheduled for spring 2023 in Moldova, and later in Spain and the UK. The absence of preconditions or pressure to agree on “common principles” was reassuring for some national leaders. But this very flexibility raised questions about the EPC’s actual value compared to the Council of Europe, which has a nearly identical membership, or regional initiatives in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. With such diverse participation and a bare-bones structure, can it achieve concrete results?

Lean institution

The EPC offers fresh opportunities for pan-European dialogue and diplomacy, at minimal financial or political cost. No other body holds biannual meetings of the leaders of almost all European countries to socialize and exchange views. The Council of Europe has only ever held three summits, with a fourth scheduled for 2023. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe has met five times at the summit level, most recently in 2010.

By design, the EPC has no secretariat, financial resources or staff. The implicit model is the G7 or G20, which hold largely informal gatherings of heads of government. “Sherpas” – senior officials – prepare their periodic meetings.

Facts & figures

EPC summit and roundtable agendas will be set by a host country that alternates between EU and non-EU members. In Prague, these focused on the main international challenges of the day. With countries as diverse as Moldova, Spain and the UK to host forthcoming sessions, maintaining continuity will be a challenge. For appearances’ sake, the British may even choose to use a label other than the EPC for their conference.

While most governments find these informal arrangements appealing, they are unlikely to satisfy fragile democracies looking for tangible support during the long period before possible EU membership. Any sign that the EPC is draining political energy from the actual enlargement process will disappoint them. Without even a modest institutional structure, the EPC is unlikely to deliver enough concrete benefits to convince countries in the EU’s waiting room to be patient.

EU-centrism

The European Commission seems the obvious body to provide continuity between summit meetings. It has relevant experience and could develop projects with EU candidates and other European states. This might seem natural, as the 27 EU members form a majority of the EPC, and the EU’s top two officials participate in its meetings.

But the Prague session moved away from this model, with important roles emerging for the UK and other countries not interested in EU membership. The Czech Republic even suggested that Israel be invited; this was not taken up, and instead, the first meeting in a decade of the EU-Israel Association Council took place under the auspices of the rotating Czech EU Council presidency.

Rather, the Prague EPC summit projected a loose, pan-European identity, with all countries on equal footing. An EU-centric approach – even if more practical, in terms of organization and continuity – would hold little appeal for countries as diverse as Azerbaijan, Norway, Serbia, Turkey and the UK.

Club of democracies?

In a May speech launching the EPC in Strasbourg, Mr. Macron called for bringing together “democratic European nations that subscribe to our shared core values.” He expected the EPC to foster geopolitical alignment with the EU as well as cooperation on energy, infrastructure, migration and other areas. Some experts suggested that any joint initiatives be backed by “soft law,” such as resolutions, recommendations, codes of practice and other nonbinding measures.

Yet the European Neighborhood Policy has demonstrated the futility of a box-ticking exercise that expects countries to sign up to values they do not uphold in practice. This often leads to accusations of bad faith. Several EPC participants in the southern Caucasus, eastern Europe and the Balkans – including Turkey, and indeed, EU members themselves – do not live up to supposed European standards. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Hungary, Serbia and Turkey maintain close links with Russia.

On the eve of the summit, Mr. Macron and the Czech government emphasized that all 44 countries would gather on an “equal footing” – spurred, no doubt, by a shared sense of vulnerability after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The apparent success of the Prague summit reflected near-universal European participation, with no pressure from the EU to commit to its principles or procedures. Indeed, this was necessary for the presence of several countries that do not meet democratic standards.

Risks and uncertainties

The chief risk associated with the EPC is that it becomes a talking shop with no tangible results. This would disappoint participants, especially the most vulnerable countries. It would also exacerbate the current geopolitical void in south-Eastern Europe – leaving Russia and China to take the initiative.

Secondly, the EPC could distract from the enlargement process and internal EU reforms. Political capital could be drained from efforts to streamline EU decision-making to prepare for enlargement. Instead of fast-tracking membership for countries in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, the EU would waste its efforts on a new forum that overlaps with, and may even weaken, existing structures.

The EPC may be perceived in the Kremlin as a way of taunting Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In addition, the EPC (like the EU’s Neighborhood Policy and its Eastern Partnership) may end up being seen in eastern Europe as a diversion from EU membership, not as a stepping stone. This would remove incentives to actively participate in the new forum, and could weaken trust.

Finally, the EPC may be perceived in the Kremlin as a way of taunting Russian President Vladimir Putin – especially given the involvement of countries viewed by Moscow as within its sphere of influence. Such states might be pressured to leave the EPC, particularly if it heads in an EU-centric direction. Ahead of the Prague summit, French representatives made a point of denying that the EPC was an anti-Russian initiative.

Scenarios

Faced with such uncertainties, the EPC may evolve along one of several paths:

Photo opportunity

To be sure, the family photo of 44 government leaders taken in Prague Castle had a real effect. But under this scenario, Europe’s urgent security and economic challenges see the summit’s initial momentum lost. Participation at future gatherings is half-hearted, and increasingly with appearances by ministers and senior officials instead of heads of government. Roundtable and plenary discussions become desultory. No working groups convene between summits, and sherpas meet rarely (and virtually) as meetings approach. Gradually, they become less frequent.

The European Commission is discouraged from putting forward joint projects, but no other entity emerges to take on these tasks. Eventually, some minor environmental and tourism projects are identified, to be loosely coordinated by national ministries. The Polish government, perhaps, provides a suite of offices, a nameplate, and some detached officials.

An insistence by several EU countries on respecting European values and aligning with the EU’s foreign policy alienates several participants; Moscow offers them incentives to withdraw. The EPC garners little further media attention.

Fledgling forum

Under this scenario, the EPC becomes widely accepted as the only regular top-level, Europe-wide forum with all members on a common footing. In its first two years, the EPC holds four summits and develops a lean governance structure, including an independent secretariat, well-defined areas of cooperation, and a budget contributed proportionately by its members.

It meets twice yearly at the summit level under a rotating presidency, alternating between EU and non-EU hosts, and sets up working groups in agreed priority areas. These generate joint projects in fields such as security, energy, climate, infrastructure and migration. Projects are coordinated by national ministries.

Shared assessments of threats to European security are made. The EPC helps mobilize and coordinate support for the postwar reconstruction of Ukraine. It provides a setting where the UK and other countries not aspiring to EU membership can engage with EU partners. Britain hosts the fourth summit meeting, branded as the UK-European Cooperation Forum.

The EPC’s future

As the first scenario implies, the EPC may fade in line with the forces that gave rise to it. The EU – against precedent, at Washington’s urging – could put Ukraine, Moldova, and even Georgia on a fast track to membership, possibly linked to postwar reconstruction. In that case, the need for a separate European “community” may appear less acute.

By then, however, as suggested by the second scenario, the EPC may have already created habits of partnership between countries from the southern Caucasus to Iceland. If France and Germany, still indispensable agents of change in Europe, resume their usual cooperation and find a common interest in maintaining the EPC, it should have a future as the only top-level, pan-European forum for regular dialogue.