Scenarios for European Union enlargement

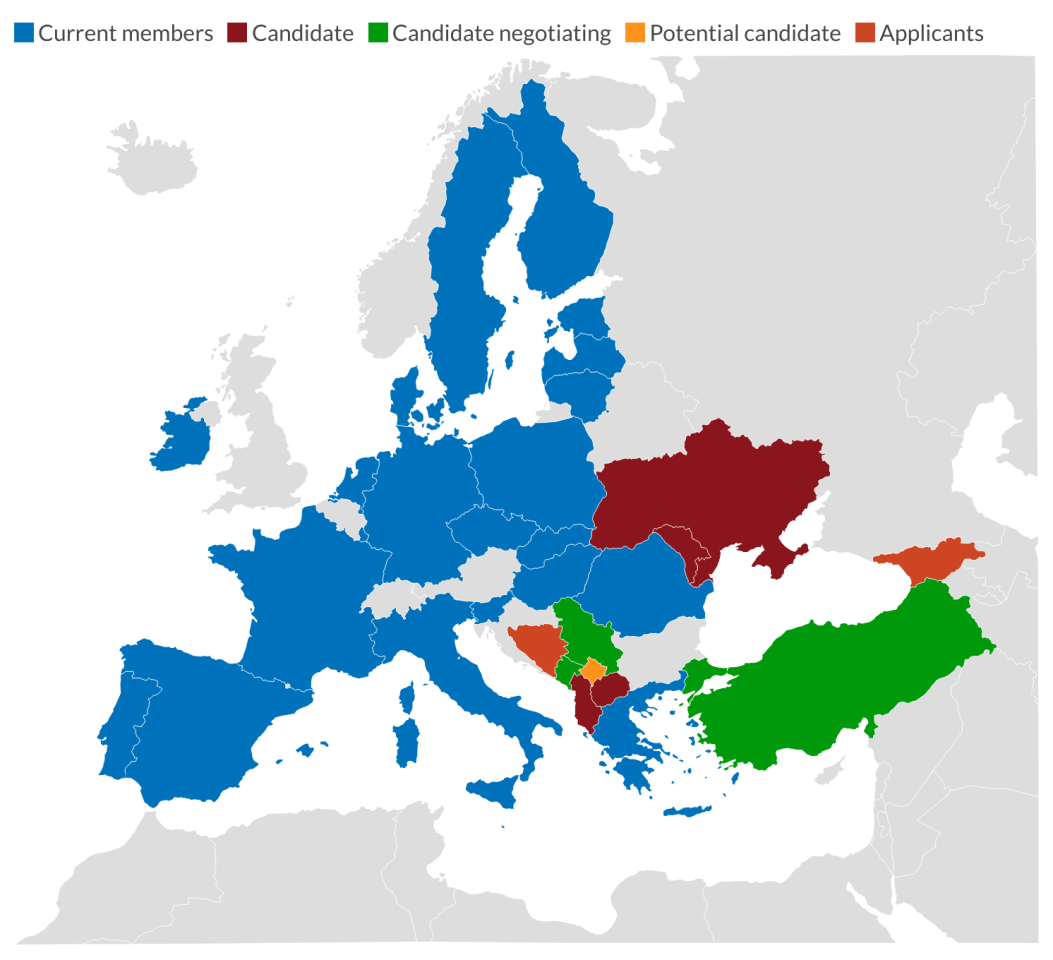

New approaches to EU enlargement could hasten the benefits of integration to such candidate countries as Ukraine and Moldova.

In a nutshell

- The classic path for EU enlargement is slow to realize results

- Proposals for more graduated accession are drawing fresh support

- A broader, parallel Europe-wide forum is also being proposed

In June, European Union leaders granted candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova as a signal of solidarity in response to Russian aggression. Yet despite the urgency of the situation, the EU refused to fast-track membership, as requested by Kyiv, and kept Georgia in the waiting room. Candidate status implies decades of efforts to implement EU laws and standards before membership is granted; war and occupation pose further obstacles. Still, other initiatives are on the table that could speed up the EU’s response and push back against Russia’s bid to reestablish a sphere of influence in Europe.

Ukraine applied for EU membership four days after Russia’s February invasion, to show Moscow that it had Brussels’ support even as the path to NATO remained closed. Moldova and Georgia quickly followed suit. The European Commission swiftly examined these applications and recommended that Ukraine and Moldova be granted candidate status, subject to certain conditions. Georgia, in its view, needed to strengthen its democratic credentials before taking this initial step toward membership.

EU heads of government endorsed these recommendations in a show of unity, overcoming the skepticism toward enlargement lingering in some capitals. These doubters, such as Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa, considered military and economic assistance to Ukraine more valuable than largely symbolic gestures that could raise false hopes. But geopolitical considerations prevailed. European leaders hoped, too, that the prospect of membership, however distant, would give beleaguered applicant countries incentives to strengthen democracy and fight corruption.

Three scenarios for enlargement, once touted as the EU’s most effective foreign policy, present implications for the future architecture of Europe.

The classical approach

Candidate status is a first step on the long road to EU membership. To advance, candidates need to prove that they respect democracy, the rule of law and human rights, and that they have competitive market economies as well as the institutions needed to implement EU laws and rules.

They must also show they will not import instability into the Union, notwithstanding war or foreign occupation. If Ukraine becomes a member, the EU will share a border with Russia some 2,000 kilometers long. Under a mutual defense clause, EU countries would then be committed, in principle, to defend Ukraine against any future Russian attack. Yet European leaders naturally shy away from direct confrontation with a nuclear-armed Russia, and the EU has only an embryonic security and defense capability.

To admit a new member, the EU must also be convinced that it can sustain further enlargement while maintaining the momentum of European integration; ensuring its own governability; and advancing such varied priorities as the single market, the euro, the Schengen system of open internal borders, migration and asylum policy, energy security, climate policy, digitization, security and defense. Some consider that this calls for a new treaty to deepen European integration before further enlargement.

Membership for Ukraine would change the balance of power in the EU.

Membership negotiations, when they finally begin, are a way for candidates to prove that they can implement EU rules across more than 30 complex policy areas. All 27 current member states can veto any step that they believe threatens their interests. Enlargement negotiations would move ahead more rapidly if the EU could approve candidates’ progress in more technical areas by a qualified majority vote, instead of by the unanimous decision now required.

Ukraine has a large, relatively poor population, with far more agriculture workers than EU countries. Under existing rules, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia would be eligible for substantial subsidies as members. Existing members would have to pay up or reduce their own benefits to accommodate the poorer newcomers. Corruption and governance issues pose further problems, now temporarily obscured by the outpouring of sympathy following Russia’s invasion. Membership for Ukraine, a country around the size of Poland and Spain, would change the balance of power in the EU and spark a tough debate about the weight of votes among member states.

The classic approach to enlargement delivers a message of solidarity and could create incentives for reform. But after an initial morale boost, disappointment would set in if membership prospects recede, as happened with the Balkan applicants and Turkey.

A graduated approach

Such risks and uncertainties have led several political leaders and observers to suggest a new approach that would deliver some of the benefits of membership more quickly.

EU accession today is a binary process, under which a country is either in or out. There is no alternative to “full membership” covering all aspects of the EU’s activities (apart from limited opt-outs). This zero-sum model has contributed to the impasse in membership talks with Montenegro, Serbia and other Balkan countries. Applicants have been kept waiting for decades after being given a “European perspective” or the coveted title of “candidate,” until they fulfill increasingly demanding conditions and resolve problems with neighbors.

Frustrated governments ask why they should adopt EU legislation or make costly reforms when their prospects for membership are so uncertain. In several cases, a slide toward authoritarian rule or “democratic stagnation” has followed. Enlargement skeptics in the EU take this as further evidence that candidates are not ready for membership; the result is a vicious cycle, and mutual criticism.

Facts & figures

According to Charles Michel, President of the European Council, “gradual and progressive integration during the accession process” could solve the slow pace of membership talks. Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg advocates early participation of neighboring countries in the single market, EU programs and decision-making institutions.

Researchers have gathered such ideas together in a staged accession model, in which an applicant country gradually assumes membership rights and duties. At each stage, incentives would be offered – such as more say in EU institutions, or increased financial support – in recognition of the progress made. A “reversibility mechanism” would protect the EU from the kind of democratic backsliding that has given enlargement a bad name.

Such an innovative approach would require treaty changes. Until recently, this might have been fatal, as the EU rests on a delicate balance of interests, and governments are wary of referenda. But a treaty change no longer seems anathema to key member states – indeed, a kind of grand bargain on both widening and deepening may be necessary for enlargement to move ahead.

But the need for a swift response to the three membership applications that followed Russia’s attack on Ukraine precluded deliberation on a new model. Any departure from precedent might have been perceived in Kyiv, Chisinau and Tbilisi as a kind of second-class membership offer. Still, graduated accession might look more attractive to both new and old candidates if the enlargement process once again gets bogged down.

A European political community?

European leaders and policy experts have suggested a third means of cutting through the delays that come with the conventional approach to enlargement. French President Emmanuel Macron has proposed to the European Parliament a “European political community” that could be quickly established, permitting “democratic European nations … to find a new space” for cooperation across a wide range of fields. EU ambassadors in Brussels have debated a French “non-paper” setting out these ideas in more detail.

Despite some skepticism, initial reactions were broadly favorable, provided that such structures would add value and not replace the enlargement process. Its geographic scope needs to be clarified; for example, would it permit the participation of the United Kingdom, as one think-tank proposal for a “Continental Partnership” allowed, or be confined to countries with close links to the EU or those aiming to join it?

Enrico Letta, leader of Italy’s Democratic Party (PD) and a former Italian prime minister, proposed the rapid creation of a 36-state European Confederation – open to EU countries, the three latest applicants, and the six Balkan aspirants. He sees this as an immediate response, creating a common framework for dialogue while candidates pursue membership in parallel talks and the EU strengthens its institutions.

Graduated accession might look more attractive if the enlargement process once again gets bogged down.

Mr. Michel endorsed such an approach “to forge convergence and deepen operational cooperation to address common challenges, peace, stability and security on our continent.” Former Finnish Prime Minister Alexander Stubb added his voice to those calling for a multitiered confederal Europe, as a way to include states that may not be ready for, or may not be seeking, EU membership.

An umbrella organization, as outlined by Messrs. Macron, Letta, Michel and Stubb, would deliver a message of political solidarity and inclusiveness and could lead to new forms of “differentiated integration.” It might prove useful for promoting postwar reconstruction in Ukraine and reform throughout Eastern Europe while EU membership negotiations go ahead in parallel. But to win acceptance, it would need to be a stepping-stone to eventual membership, not an alternative to it.

An inclusive approach

Europe’s future architecture is likely to draw on all three methodologies. The classic approach to enlargement remains the policy of choice. But it could become more effective through gradual moves toward the candidates’ involvement in EU institutions, with more financial support, in exchange for better governance and EU-oriented reforms.

In parallel, an umbrella political community of democratic European states, linked to the EU, could gain traction if it offers tangible value. Above all, the EU will need to maintain a credible, inclusive and energetic approach to enlargement to retain the confidence of applicant states and resist Russian aggression.