Estonia outperforms the EU

In Europe, Estonia is one of the star performers in terms of economic growth and development and technological advancement. It faces three big dilemmas: defensive vulnerability, the non-integration of its Russian minority and rising nationalism.

In a nutshell

- Estonia is catching up with other Nordic states

- It has little reason to fear a military attack from Russia

- Rising nationalism and segregation are two big challenges

In an otherwise sluggish European Union, Estonia has a well-established record as a star performer. Powered by strong economic growth, Estonians’ purchasing power has increased 400 percent over the last two decades. Life expectancy has risen from 66 years in 1994 to 77 years in 2016. The World Bank recently classified Estonia as a “high-income country,” and its days of receiving structural aid from the EU are coming to an end.

Although still considered a “transition economy,” Estonia outperforms most other EU members. At 9.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), its public debt is a mere trifle, and its unemployment rate is 5.3 percent, well below the EU average. The country ranks high in the Human Development Index, and does well in measures of economic freedom, civil liberties, education, and press freedom.

Emerging as one of the most digitally advanced societies in the world, Estonia became the first country to hold national elections over the internet (in 2005), and the first to provide e-residency (in 2014). Its corporate tax system has also been helpful in boosting foreign high-tech investments and economic growth.

The explanation for the Estonian success story can be found in its cultural heritage.

These achievements have often been ascribed to the strongly pro-market agenda associated with Prime Minister Mart Laar, in the crucial years 1992-1994 (and again in 1999-2002). Yet there is a more comprehensive explanation for the Estonian success story: its cultural heritage.

Nordic leader

Beyond geographical location and a common heritage of Soviet occupation, Estonia does not have that much that links it with the other two Baltic states. The Estonian language is very close to Finnish and its history is intertwined with Sweden’s. In contrast to Estonia’s Nordic heritage and identity, Lithuanian culture is rooted in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Latvia is the most heavily Russianized of the three.

In the 1930s, Estonia was on par with or even more developed than neighboring Sweden and Finland. Then followed four decades of deeply destructive Soviet rule. The big question now is if Estonia is about to reclaim its former position as a leading country in the Nordic region. Given that Sweden and Finland are among world leaders in international rankings of social and economic achievement, the bar is high. Yet, the odds for continued success are good.

Facts & figures

In a recent country study, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) heaps praise on Estonia’s achievements. These include strong economic growth, as well as the lowest public debt and highest Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results in the organization. Social and environmental conditions have improved, and Estonia is a European champion of e-government. Caveats are limited to slowing economic growth and insufficient action to tackle environmental issues and inequality.

Beyond short-term needs for fine-tuning economic and environmental policies, the government in Tallinn faces three major challenges that will determine the country’s outlook.

Defense vulnerability

The first and most obvious threat is the ever-present fear of a Russian military attack. Following Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, NATO played up a “Narva Scenario,” with the results suggesting that Estonia’s eastern border region of Narva could become the next Donbas. In a series of war games conducted between summer 2014 and spring 2015, the Rand Corporation demonstrated that the Russian armed forces could easily overwhelm Estonia – and Latvia – and that there was nothing that NATO could do to defend its most exposed members.

While the message of such exercises cannot be dismissed out of hand, it suffers from the problem inherent in all war games. Moving flags on boards may clarify what could be done, but the implied scenarios often come up short on why the aggressor would make its move.

NATO expansion into the Baltic states has made a big difference. Given the risk of provoking an armed conflict it could not hope to win, Russian military aggression would have to be associated with substantial benefits. It is hard to see what those benefits could be in Estonia’s case. There was a time when the Soviet military derived significant gains from holding Estonia, ranging from ports and airfields to forward-based radars, but with modern standoff technology, the battlefield has become much less dependent on territory.

A more complex challenge would be a limited incursion by “little green men,” aiming to shame and humiliate NATO. The implied deniability would make it difficult to invoke Article 5 on collective defense laid out by the NATO treaty. But even this scenario is short on realism.

Zealously living up to its commitment to spend two percent of GDP on defense, Estonia has done much to provide for its own security, ranging from conscription for all males to the creation of a volunteer paramilitary Defense League. Numbering 26,000 men and women, the latter can mobilize and deploy within hours. Special forces from the United States also practice insertions behind enemy lines, in case of a Russian invasion.

The likely outlook for relations with Russia is that Estonia will have to put up with more of the same, with harassment that ranges from cyberattacks to cross-border kidnappings of security personnel. While this will be both costly and disruptive, it is a far cry from outright military aggression. There is also little to suggest that such fears have any impact on foreign investment and economic growth.

Russian-speaking minority

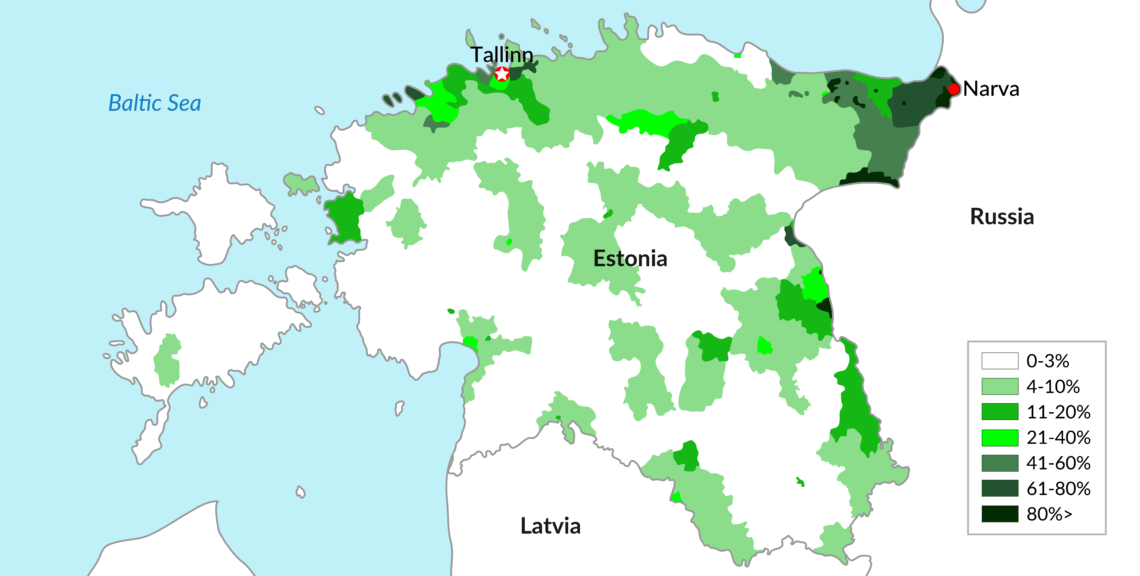

A second and considerably more complex issue concerns the sizable Russian-speaking minority that some military strategists portray as a fifth column. Although there is little to suggest that the Kremlin has been successful in mobilizing this resource, there is ample evidence that the Russian speakers are isolated from the majority population.

Estonian experts claim that 90 percent of Russian speakers have by now been successfully integrated, as citizens or as loyal permanent residents. The situation is better described as peaceful coexistence.

A closer look at the labor market, housing and schooling will show that Estonia remains a deeply segregated society.

A closer look at the labor market, housing and schooling will show that Estonia remains a deeply segregated society. The government has attempted to counter this segregation by offering Russian-language broadcasting, via the ETV+ channel, but the programming is considered inferior to that offered by Russian channels such as Russia One. Many Russian speakers still get their news from the Kremlin.

Although the present situation is a far cry from the time of regained independence, when some Estonians feared they were about to become a minority in their own country, the problem of segregation cannot be dismissed out of hand. The case of Narva, which is almost 100 percent Russian-speaking, may serve to illustrate the situation.

On one hand, those who cross daily into Russia are aware of the difference in living standards and will not be receptive to calls for unification. On the other, it may not be obvious to them what benefit there is in assimilating. Becoming an Estonian citizen not only means having to learn the Estonian language, which can be quite a challenge, especially in a region where the lingua franca is Russian. It also means getting an Estonian passport, which will complicate travel to Russia, where many still have friends and relatives.

An alternative is to accept a Russian passport. But this means serious restrictions on travel to other countries in the EU. The preferred choice for many Russian speakers has been to accept “alien” passports. Holders of these “gray passports” are allowed to travel both to Russia and to other EU member states. They enjoy the same rights to needs-based social services as do all legal residents of Estonia, and their children can go to schools and kindergarten in Estonia.

The downside is that they are barred from holding public office and from voting in national elections. Many claim to be happy to pay that price. As they retreat into the private sector, and into social networks with few Estonian speakers, segregation between the two communities is cemented.

Of the estimated 340,000 Russian speakers currently living in Estonia (27 percent of the Estonian population), less than 90,000 have Russian passports and about the same number have gray passports. The latter number is down from 170,000 at the time of the last census in 2000. It may therefore be tempting to view segregation as a problem that will vanish over time. A recent study of young Russian-speaking adults has also suggested that only about 12 percent might constitute a potential threat in the event of a Russian hybrid war.

The challenge to the government rests in Estonia’s small geographic size and declining population. The total number of people living in Estonia in 1990 was 1.6 million. Today, the figure is 1.3 million, of which less than a million are ethnic Estonians. From this perspective, integrating the Russian speakers becomes a question of demographic viability.

Over the past five years, Estonian political and media elites have received two important wake-up calls. While the crisis in Ukraine has driven home that there may be good reason to think a bit harder on whether the Russian speakers that live in Estonia feel at home and may be expected to be loyal.

EKRE may seek to address economic inequality through progressive taxation, undermining the pro-market agenda.

The government has taken the challenge seriously. In 2018, President Kersti Kaljulaid made a symbolically important gesture, moving her office to Narva for a month. The city is becoming a hub for arts and culture, especially in the abandoned Kreenholm textile industry complex, and the University of Tartu operates Narva College.

Military service has become the great equalizer. When Russian-speaking youngsters are drafted into the Estonian armed forces, they are treated as Estonians. If their language skills are poor at the outset, they will rapidly improve. This suggests a scenario where young Russian speakers learn the language, become citizens, serve in the military and demonstrate loyalty to the state.

The main roadblock to integration is on the Russian side. Many parents who place a premium on maintaining their Russian identity insist on placing their children in Russian-speaking schools. This restricts their career choices and helps cement the segregation of Estonian society.

Rising nationalism

A third, more recent cloud hanging over the Estonian success story derives from the outcome of national elections in March 2019. The winner was the liberal Reform Party, with 28.9 percent of the vote, followed by the ruling Center Party at only 23.1 percent. The real sensation was the nationalist Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE by its Estonian acronym), which came in third. With 17.8 percent of the vote, it tripled its returns from 2015. Its rise follows a common European pattern of nationalist right-wing campaigning against multiculturalism, LGBT rights and feminism.

Stunned by EKRE’s strong showing, many liberal observers believed that Prime Minister Juri Ratas would invite the Reform Party to join a coalition government. To their dismay, he preferred to join with EKRE and the conservative Pro Patria. For good measure, EKRE leader Mart Helme and his son Martin Helme, the leader of EKRE’s parliamentary group, were given the key portfolios of Interior and Finance.

Reactions from the liberal media have played up fears that the surge of the nationalist agenda would result in self-censorship, with journalists being told by editors to tone down critiques of EKRE. Such concerns are belied by the Estonian media’s ranking as the 11th-most free in the world. There is considerable resilience here.

Another cause for worry is that EKRE may seek to address economic inequality through progressive taxation and other social measures that may undermine the pro-market agenda. Such fears should be measured against the robust societal institutions that have supported educational achievements and the rise of high-tech industries.

What may give rise to more serious concern in pro-European circles is that the rise of EKRE also follows a pattern of profound euroskepticism already set by the True Finns in Finland and by the Sweden Democrats in Sweden. Although critique against immigration has been a dominant factor in the rise of all the Scandinavian nationalist parties, it is not the whole story. Finland remains ethnically very homogeneous, and Estonia has received very few refugees.

Finnish and Estonian apprehensions over having to take in migrants could lead to resentment toward Brussels. If such fears fuel a further surge of the nationalist parties, it could result in a euroskeptic northern alliance of high-performance, low-corruption countries that may influence euroskeptic circles in other member states.

Looking beyond this potential threat to EU cohesion, the outlook for Estonia remains highly positive. The odds are that the country will remain at peace with Russia, that Estonians and Russians will continue their segregated but peaceful coexistence, and that the Estonian economy will continue outperforming the OECD and EU averages.