A closer look at the Eurasian Economic Union

In theory, the Eurasian Economic Union should be an important economic influence globally. Yet it has struggled to find relevance, not least because it has not managed to build true economic integration. Can it overcome the hurdles?

In a nutshell

- The EAEU was set up to integrate post-Soviet economies

- It has had difficulty getting members to harmonize policy

- Russian strong-arming has led to resistance from members

Founded in 2014, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) is a consequence of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. For decades, the Soviet republics had been bound together both politically and economically. Their sudden transition to 15 independent states caused enormous difficulties. Naturally, the idea of preserving the common economic space, at least for a transitional period, was a popular one.

The first project designed to streamline the departure from the Soviet system was the creation in December 1991 of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). At its founding, the CIS included 11 of the 15 former Soviet republics: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Russia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania decided to stay out. Initially, Georgia did too, but it finally joined in 1993.

The CIS’s work was dominated by political issues, while economic relations were put on the back burner. In 1994, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev proposed the creation of a Eurasian union that would form a single economic space and ensure a common defense policy. However, the proposal garnered little support from CIS members.

For the first 10 years of post-Soviet transition, most of the former union did not preserve economic integration.

In 1995, the leaders of six post-Soviet countries – Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan – produced a less ambitious plan called the Eurasian Economic Community. When it was finally established in 2000, it did not include Uzbekistan. Tashkent signed onto the project in 2005, but then pulled out again in 2008. All this meant that for the first 10 years of post-Soviet transition, most of the former union did not preserve economic integration. Countries such as Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan chose both political and economic independence.

The principal task of the Eurasian Economic Community was to establish a common economic space. Dubbed the Eurasian Customs Union, the project finally came to fruition in 2010 and included Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. When the EAEU was established in 2014, it absorbed the Customs Union into its legal framework. The EAEU came into force on January 1, 2015.

Facts & figures

Resistance to political integration

In 2013, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev made clear his country’s position on attempts to move from economic to political integration of the EAEU:

The politicization of the union being created is unacceptable. Such areas as border control, migration policy, defense and security, as well as health, education, culture, legal assistance in civil, administrative and criminal cases do not belong to economic integration and cannot be transferred to the format of the economic union. As sovereign states, we actively cooperate with various countries and international organizations, without infringing on mutual interests. The Union should not interfere with us in this direction.

As it turned out, the various members had differing visions for this new partnership. In 2012, Russia proposed the creation of a Eurasian Parliament to go along with the Customs Union. The other members, wanting to limit integration to economic matters, rejected this proposal. A move to introduce a common currency was also rejected.

Operation

The EAEU’s work is led by the Eurasian Economic Commission, while strategic issues are decided by the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, comprised of the heads of state of the EAEU members. Economic integration occurs through the Customs Union, which has established a regime for the free movement of goods within the EAEU. The Customs Code allows member states to unify and harmonize national procedures for internal trade.

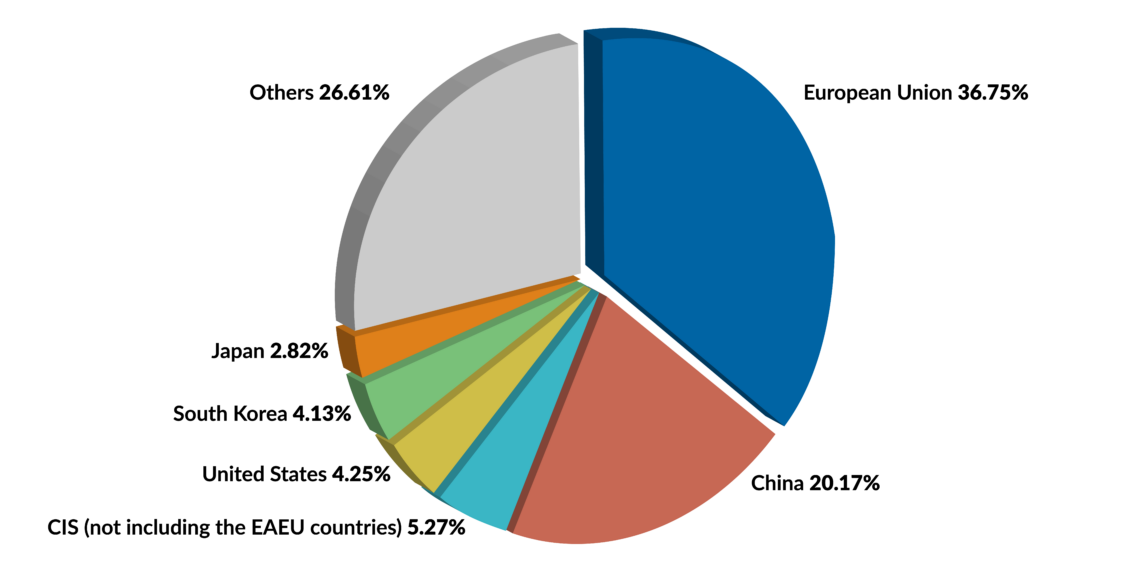

The EAEU tries to pursue a unified foreign trade policy with third countries. Within this framework, countries are meant to apply uniform regulations and tariffs, as well as antidumping and other measures to protect the domestic market. Exceptions remain, including those mandated by the World Trade Organization.

The foundation of the EAEU common market is regulation aimed at removing technical barriers to trade between the member states. By 2018, uniform requirements were established for a wide range of goods: 46 technical regulations were adopted in the Customs Union, and 40 of them are already in force. Most other goods are covered by a common regulatory framework. The EAEU is also working on creating a common market for medicines, as well as coordinating national competition, agro-industrial and transport policies.

Facts & figures

The EAEU represents a significant chunk of the global economy. According to the World Bank, the EAEU’s combined gross domestic product (measured by purchasing power parity) came to $4.9 trillion in 2020. In comparison, Germany’s was $4.5 trillion. EAEU exports are dominated by mineral products (oil, gas, nonferrous metals, coal), which comprise 54 percent of the total volume. These are primarily produced by Russia, though Kazakhstan’s contribution is also quite large.

Difficulties

The EAEU’s main problem is Russia’s immense economic weight. In 2020, it accounted for more than 90 percent of the organization’s GDP, and the integration process is therefore heavily tilted toward Russian interests. This imbalance frequently causes conflicts on economic issues with other member states. For example, Belarus and Russia often disagree about how much the former should pay the latter for natural gas deliveries. Every year, Moscow shoots down Minsk’s proposal to set the price at the same level as inside Russia, and difficult negotiations follow. Moreover, member states frequently place restrictions on agricultural products from other countries within the union.

Industrial cooperation is low, while protectionism is high.

Such conflicts strengthen the trends pulling at the economic seams of the EAEU. The result is that EAEU states’ trade with external countries – especially China – is rising faster than with other members of the union. Also, Chinese and American investment flows far outstrip those between EAEU countries. Furthermore, cooperation with third countries lacks coordination and harmonization. For example, Armenia’s economic agreements with the United States and European Union diverge from EAEU requirements in several areas. Kazakhstan joined the World Trade Organization by agreeing to set customs duties lower than the “unified” rate mandated by the EAEU. Russia is the only member that does not allow EU and U.S. citizens short-term, visa-free entry into its territory.

It is also worth noting that there are no truly trans-Eurasian corporations or common Eurasian projects. Currently, Russia mainly allocates its resources to bilateral projects and political support – neither of which leads to policy harmonization or EAEU interconnectedness. National industrial and agricultural policies remain uncoordinated. There is no general regulatory framework for taxes. Industrial cooperation is low, while protectionism is high. A lack of significant resources at the EAEU level results in the dearth of mutual investments and the dominance of American and Chinese money coming in.

Finally, the EAEU’s common cultural and educational space is gradually eroding. These issues have dropped from the organization’s agenda, leaving individual states to ramp up support for their own national cultural priorities and historical narratives. They have also reoriented their educational systems toward American, European and Chinese standards and centers of learning, undermining any momentum toward EAEU cooperation on this front.

Facts & figures

EAEU: Economic indicators

- Total GDP: $1.74 trillion (3.2% of world GDP)

- Total population: 184 million (2.4% of global population)

- Economically active people: 93.6 million (2.7% of global total)

- Unemployment: 4.8%

- External trade with third countries (2020): $731 billion (2.4% of global export)

- Population with internet access: 83.7% (3.9% of total internet users globally)

- Agricultural production: $114.5 billion (2.6% of global production)

- Industrial production (2020): 2.2% of global industrial production

- Oil production: 600 million tons (14.4% of global production)

- Gas production: 750 million cubic meters (19.5% of global production)

- Power generation: 1,256.3 million kilowatt-hours (4.7% of global production)

- Steel production: 84.3 million tons (4.2% of global production)

- Mineral fertilizers production: 17 million tons (35.7% of global production)

- Rail mileage: 145,500 km (10.3% of global rail mileage)

- Roads: 1.76 million km (4.5% of global)

Source: Eurasian Economic Union

Russian dominance

Since Russia plays such a dominant role in the EAEU’s economy, the organization’s prospects depend on what happens there. From this perspective, we can see how old ways of thinking about “spheres of influence” have led some Russian leaders to consider EAEU partners as mere extensions of their country’s own territory. For example, some members of the Russian State Duma (the legislature) have recently said that Kazakhstan’s northern reaches were “gifted” to that country by Russia. The sentiments echo a statement Russian President Vladimir Putin made in 2014 that before the collapse of the Soviet Union, “the Kazakhs never had statehood.” Unsurprisingly, such statements have caused a wave of indignation within Kazakhstan.

EAEU member states may begin to resist integration within the framework.

In Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko, who is using illegitimate means to hang on to power, is gradually ceding his country’s sovereignty over to Russia to preserve his regime. In September 2021, under pressure from Moscow, Minsk agreed to 28 “road maps” for closer integration with its neighbor to the east. President Putin described them as a “serious step toward creating a common economic area.” Crucially, Russia has been ramping up its military presence in Belarus as well. When the inevitable transition of power finally comes in Belarus, it will likely lead to a revision of its relationship with Russia toward more independence and a shift of focus from east to west.

Russia also has a military base in Armenia, which boosts the latter’s security in the face of its ongoing conflict with Azerbaijan. The Armenian government cannot risk losing Russian security support, limiting its ability to develop independent foreign and economic policy.

Scenarios

All of this means that if Russia continues to push so hard to restore and strengthen its sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space, EAEU member states will begin to resist integration within the framework. That tension will put an end to the EAEU’s recent attempts to conduct relations with the EU on equal footing. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia are already trying to establish bilateral economic relations with other parts of the world without the participation of the EAEU.

Another scenario would see Russia adjust its foreign policy agenda to focus more on the pan-European space, with less strong-arming of its neighbors. If that were to occur, other EAEU members would likely lose interest in the organization and look toward potential partnerships with the EU, or even membership. Something like this occurred in the late 1980s with the democratic transformations that were taking place as the USSR was winding down. Despite the attempts at integration described above, most of the 15 former Soviet states distanced themselves from Russia to some degree. What is happening with the EAEU is the final stage of this trend.

It seems that in any realistic scenario, the prospects for meaningful economic integration in the EAEU are slim to none.