Ethiopia under strain again

The Nobel Peace Prize-winner prime minister of Ethiopia has made headway implementing his ambitious political reform agenda. However, the global pandemic put the changes on hold and the country’s political and economic outlook has darkened considerably.

In a nutshell

- The pandemic-related delay of a national election has put Ethiopia in a tight constitutional spot

- A sharp economic slowdown has also awakened its plague of ethnic distrust

- The government is struggling to keep its reform drive alive

After two years of accelerated changes and reforms, 2020 was supposed to be a watershed year for Ethiopia – a significant regional power in Africa, its symbol of resistance to foreign domination and, to many, the ultimate example of the “African renaissance.” However, the coronavirus pandemic and resulting lockdowns have thrown big roadblocks in front of its leader’s economic and political agenda.

On March 30, Ethiopia’s National Electoral Board (NEBE) decided that the elections scheduled for August 20 could not be held because of the public health hazard. Days later, the parliament sanctioned the indefinite delay. With the already fragile mandate of the House of Peoples’ Representatives and Regional Legislative Councils (elected under questionable circumstances in 2015) due to expire by September 30, a temporary deal by the country’s main political actors is the only alternative to scenarios of conflict and political fragmentation. The term of the government, headed by Nobel Peace Prize recipient Abiy Ahmed, expires on October 10, 2020.

Underneath Ethiopia’s relatively successful developmental strategy is a complex political trajectory.

The government has presented four alternative ways for avoiding the constitutional and governance crisis: the dissolution of the parliament under the terms of the country’s constitution; an extension of the state of emergency declared in April; a constitutional amendment; and asking the House of Federation (the upper house of the country’s bicameral legislature, the Federal Parliamentary Assembly) to provide an interpretation of the constitution on the issues. The last option was chosen by the ruling Prosperity Party’s Central Committee without consulting two other key political forces: the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).

A giant with feet of clay

Underneath Ethiopia’s relatively successful developmental strategy is a complex political trajectory. For nearly 30 years, the country of 108 million people and more than 90 ethnic groups experienced tensions and impulses toward fragmentation that were contained by the single-party regime of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The EPRDF was an armed coalition responsible for defeating the Marxist dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam. Since 1995, the party’s power was consolidated and sustained on the basis of its liberation credentials, accelerated growth, coercion, the charismatic leadership of Meles Zenawi (1995-2012) and a fragile ethno-federal architecture.

Facts & figures

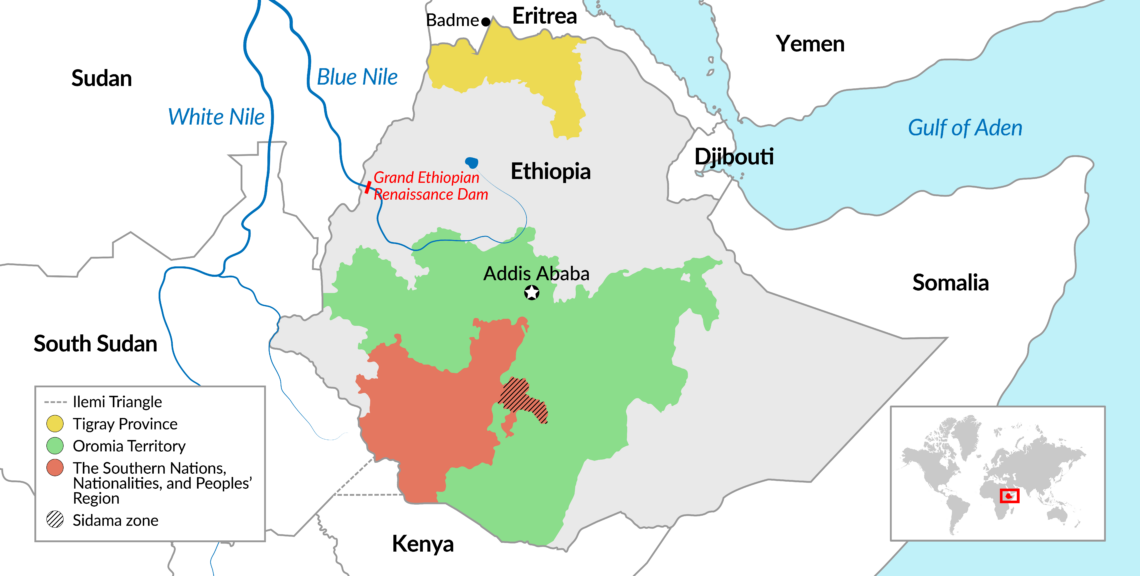

Ethnonationalism has always been a driving force of Ethiopia’s politics. It was the leading mobilization factor against the Derg (the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, a Marxist-Leninist military junta that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987), with the EPRDF becoming a coalition of the country’s four main ethnic groups: the Oromo, the Amhara, the Tigray and the Southern Nations. However, whereas the Oromo and the Amhara are the largest groups, the Tigray – which account for about 6.1 percent of the population – have played a dominant role in the political and military structures since the fall of the Mengistu regime.

2015 protests

The limits of this model of authoritarian ethnofederalism became apparent by 2015, with the Oromo protests. The trigger was the federal government’s plan to expand the capital city Addis Ababa into Oromia territory, splitting the Oromo communities into different administrative provinces. Their manifestations of discontent, initially limited, spread quickly throughout the country as others – including the Amhara and groups in the Southern Nations regional state – took to the streets in protest. Faced with such an unprecedented wave of contestation, a pressured and increasingly divided EPRDF opted for reforms. This led to the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn (2012-2018). The ascension to power of Mr. Ahmed, a 44-year-old Oromo, signaled a generational and ethnic revolution in Ethiopian politics.

The new prime minister implemented a series of fast and sweeping political changes. They included the release of prisoners, the welcoming of political exiles back in the country and a peace agreement with neighboring Eritrea, which won Prime Minister Ahmed the Nobel award in 2019. However, in a moment marked by institutional fragility, political and ethnic polarization and economic challenges, the opening of the political space led to the emergence of multiple parties and movements. After a period of relative calm, ethnic tensions and social contestation increased rapidly throughout the country.

Among the many reforms introduced by Mr. Ahmed, the boldest was the creation of the Prosperity Party in December 2019. It is a political platform to expand the power structure and reshape the precarious ethnic and political balance established by the EPRDF. The once all-powerful structure was broadened and made more ethnically-inclusive. The new body’s vision for national progress and prosperity is expected to bind Ethiopia’s diverse constituencies. However, the Tigrayan front has refused to join the new party. TPLF activists perceive it a threat not only to the generations that governed Ethiopia over the last decades but also to local autonomy.

Conflicting aspirations

The fast and far-reaching political changes coming from Addis Ababa have revived many of the old tensions and resentments, as evidenced in an increase in hate speech and ethnic tensions throughout 2019. The power shifts prompted in the central province by the government in Addis Ababa have led to clashes between the country’s main ethno-political groups, with the once-dominant Tigrayans now feeling persecuted by the Amhara and the Oromo.

Autonomy claims increase and important regions such as Tigray and Amhara invest in their paramilitary forces.

The Oromo youth spearheaded the 2015 protests that eventually elevated Mr. Ahmed in power, yet the Oromo Liberation Front distrusts what it sees as the prime minister’s nationalist impulses. The pandemic motivated the two sides to call a truce, but it is not expected to last. The TPLF, in turn, has been more vocal in its opposition to Prime Minister Ahmed, presenting itself as the champion of Ethiopia’s ethno-nationalist aspirations against a centralizing regime. Tensions have practical implications for the country’s political and security outlooks, as autonomy claims increase and important regions such as Tigray and Amhara invest in their paramilitary forces.

A further destabilizing factor is the peace agreement signed with Eritrea in 2018. Still far from fully implemented, it has fueled internal tensions in Ethiopia easily explained by geography. The war between the two countries (1998-2000) was over territorial claims, in particular the border town of Badme in the Tigray Region, the northernmost area of Ethiopia that shares a long border with Eritrea. A United Nations-backed special court ruled in 2002 that Badme and other disputed territories lie in Eritrea. The verdict was accepted by Addis Ababa. However, many Tigrayans see it as arbitrary and illegitimate. Recently, the tensions between the TPLF and the Eritrean ruler Isaias Afwerki have escalated.

The border between the two countries has been shut. For President Afwerki, the head of one of the world’s most oppressive dictatorships, sharing an open border with a hostile region would be too high a risk.

The Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) is also at a critical juncture. Throughout the last decades, the country’s strong and well-trained army was a stabilization factor both internally and regionally. It functioned in a close symbiosis with the political and economic elite. However, the rising political costs of repressing dissent since 2015, the internal divisions in the force along ethnic and generational lines and the 2019 coup attempt (led by a faction in the security forces) all have undermined the military’s position.

Facts & figures

Ethiopia, a snapshot

Population (July 2020 est.)

108,113,150 (second-most populous country in Africa)

Ethnic groups (2007 est.)

Oromo 34.4%, Amhara (Amara) 27%, Somali (Somalie) 6.2%, Tigray (Tigrinya) 6.1%, Sidama 4%, Gurage 2.5%, Welaita 2.3%, Hadiya 1.7%, Afar (Affar) 1.7%, Gamo 1.5%, Gedeo 1.3%, Silte 1.3%, Kefficho 1.2%, other 8.8%

Religions (2007 est.)

Ethiopian Orthodox 43.5%, Muslim 33.9%, Protestant 18.5%, traditional 2.7%, Catholic 0.7%, other 0.6%

Economy

Ethiopia is a one-party state with a planned economy. For more than a decade before 2016, its GDP grew at a rate between 8% and 11% annually – making it one of the fastest growing among the 188 IMF member countries. This rapid growth was driven by government investment in infrastructure, as well as a sustained expansion in the agricultural and service sectors. More than 70% of Ethiopia’s population remains employed in agriculture, but services have surpassed it as the principal source of GDP. Despite its impressive growth, Ethiopia remains one of the poorest countries in the world due both to rapid population expansion and a low starting base

Source: CIA World Factbook

This weakness is particularly relevant when deteriorating regional stability is a cause of concern for Addis Ababa. It has disputes with Kenya over their joint presence in Somalia (as a part of AMISOM, African Union Mission in Somalia). The contest over the disputed “Ilemi Triangle” bordering Ethiopia, Kenya and South Sudan also escalated following the shooting down by the Ethiopians of a Kenyan plane carrying medical supplies in Somali territory.

Relations with another regional power, Egypt, have also reached a critical phase. The point of contention here is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Nearly three-quarters of the construction work is complete and Addis Ababa has announced its intention to start filling the dam in mid-July, despite the lack of an agreement with Egypt and Sudan protecting these countries’ water interests. Cairo has recently complained to the UN Security Council, accusing Addis Ababa of diverting Nile waters. A diplomatic solution remains likely, however. The GERD is a vital project for Ethiopia’s ambition to become an industrial powerhouse and Africa’s leading energy producer.

Economic plans

Economic growth, poverty reduction and stabilization were the backbones of the EPRDF’s success. Presenting himself as a reformer, Prime Minister Ahmed emphasizes accelerating the country’s development trajectory while opening the political space under a nonnegotiable nationalist framework. Recently, the International Monetary Fund announced a $3 billion loan to Ethiopia to support the government’s ambitious Homegrown Economic Reform agenda. It aims to shift from public- to private-sector-led growth.

Some 30 million Ethiopians are expected to need emergency food assistance or cash.

However, structural reforms are now on hold amid the political uncertainty and adverse economic outlook caused by Covid-19. Some 30 million Ethiopians are expected to need emergency food assistance or cash transfers.

Scenarios

Faced as it has been with political tensions, institutional frailty and the contraction caused by the pandemic, Ethiopia remains an economic powerhouse and a key regional actor. Its outlook will largely depend on the government’s ability to navigate the upcoming period. Three scenarios warrant consideration.

Progressive Stabilization

This script is the most likely to materialize. It sees the country weathering a rocky period to return gradually to more political cohesion and economic recovery in 2021. The Ahmed government would take advantage of the exceptional context generated by the pandemic, with the opposition (except for the TPLF) more disposed to cooperate. He would consolidate the Prosperity Party’s hold on power while accommodating the demands for multinational federalism in his developmental and nationalist agenda. Substantial external aid combined with the federal state’s efficiency and experience in establishing relief networks would strengthen the prime minister’s popularity. The appeal of those challenging his mandate would decrease. While tensions remain, especially in the Tigray region, the truce – even if temporary – between the country’s political and military elites would prevent political fragmentation or disintegration. Under this scenario, Addis Ababa comes out of the pandemic better prepared to address regional challenges.

Political Fragmentation

Under this slightly less likely scenario, nationalist claims in Tigray and Sidama (where in November 2019, most of the population voted for the creation of an autonomous region), put in motion centrifugal forces and usher a long period of uncertainty. This adverse scenario hinges on a combination of factors, including the resumption of widespread protests driven by economic and political issues and clashes between Addis Ababa and several regions over secessionist or autonomic aspirations.

If the government is unable to mitigate the pandemic-wrought damage and the TPLF presses ahead, as it has announced, with a plan to conduct elections in the Tigray, Prime Minister Ahmed will find his government in a tough position. If he attempts to block the balloting with force and sends army units into the province, clashes with paramilitary forces will likely follow. Ultimately, the Tigrayans would invoke Article 39 of the Ethiopian constitution, which grants all peoples of Ethiopia the right to self-determination. This scenario adds a new layer of uncertainty in the Horn of Africa at a time of escalating tensions between states, rising security risks, multiple humanitarian challenges and an adverse economic outlook.

Disintegration

The fragmentation scenario represents a political process, but there is an alternative script – of combustive state disintegration. Such a turn of events, while the least likely, cannot be ruled out. A deepening of Ethiopia’s political and economic woes could lead to an eruption of ethnic conflicts and ethno-nationalist movements resorting to armed violence. Although highly unlikely, this scenario carries far-reaching consequences for security in the Horn of Africa.