U.S.-Iran confrontation puts the EU in a quandary

The EU has hoped to make Iran an important part of its energy security scheme and still backs the nuclear deal with Tehran, from which the United States has withdrawn and reimposed trade sanctions on the country.

In a nutshell

- Unlike the U.S. and Israel, the EU still believes the JCPOA inhibits Iran’s nuclear weapons program

- Europe hoped for more business with Iran after sanctions were lifted in 2015

- Iran’s goal to ramp up hydrocarbons production and exports cannot be salvaged by Russia, China and a friendly Europe

- Tehran’s hostility toward Israel, its missile program and poor human rights record make it an easy target for U.S. sanctions

The unilateral decision by the United States in May 2018 to withdraw from the multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran and to reimpose economic sanctions on that country has strained transatlantic relations. The Iran nuclear agreement, or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was reached in Vienna on July 14, 2015, between Tehran and the so-called P5+1: the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia and China) plus the European Union. The signatories agreed that the international sanctions against Iran and its suspected nuclear weapons program would gradually be lifted.

The extraterritorial “secondary sanctions” on Iran, however, remained in force after 2015, as their abrogation is dependent on Tehran’s concessions in other vital areas: its ballistic missile program, its regional military engagement (in Syria, Iraq and Yemen), and its human rights practices at home.

Facts & figures

EU-Iran economic ties

Iranian GDP growth

- 2016: +4.3%

- 2017: +3.8%

- 2018: -4.6%

EU-Iran trade (2017)

- EU exports to Iran: 10.8 billion euros (+31.5% y/y)

- EU imports from Iran: 10.1 billion euros (+83.9% y/y)

The EU is Iran’s third largest (16.3%) trading partner, after China (19.5%) and United Arab Emirates (16.8%)

Maintaining ties

In May, U.S. President Donald Trump warned international companies to refrain from circumventing or undermining the sanctions if they valued their American business. The administration, however, agreed to allow eight countries – including China, India, South Korea, Japan, Iraq and Turkey – to import limited quantities of Iranian oil despite the ban.

Finding itself allied with Russia, China and other countries that favored keeping the JCPOA, the EU has encouraged companies to look for ways to maintain their links with Iran. However, the capacity of the Union and its member states to support their corporate ventures in Iran and shield them from American retribution is limited.

The EU wanted to import Iranian gas as part of its strategy to diversify energy supplies.

In contrast to the U.S. and Israel, the EU is sticking to the assumption that the JCPOA inhibits Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear weapons capability. The deal is believed in many European circles to strengthen, on balance, Europe’s security and hinder destabilization of the Middle East. Furthermore, the EU has much larger economic interests in Iran than the U.S.

When the international sanctions on Iran were suspended in 2015, both Brussels and European companies had high expectations for doing business with that country. Given Iran’s geographic position as a land bridge between Europe, the Middle East and the Persian Gulf, Central Asia and South Asia; its vast energy resources (the world’s second-largest natural gas reserves and fourth-largest oil reserves); and its population of more than 82 million, the Persian state was seen as a “sleeping giant.” According to this assumption, Iran’s advantages could help transform it quickly into a major energy hub and regional economic power. The EU wanted to import Iranian gas as part of its strategy to diversify energy supplies. This also served Iran’s gas export ambitions.

Facts & figures

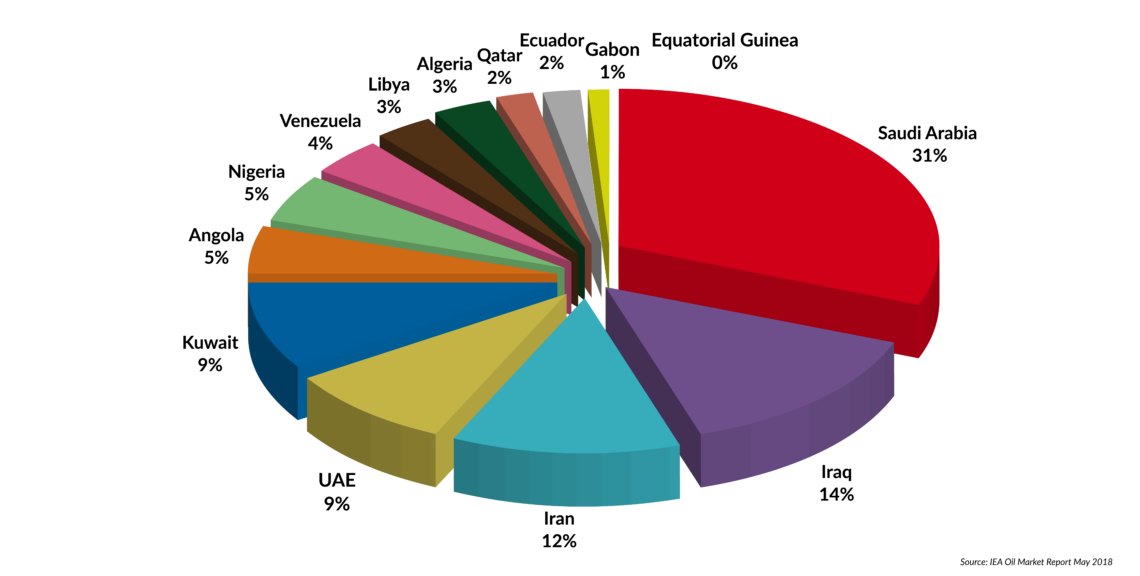

OPEC member countries' shares of oil production, April 2018

Iran’s bilateral trade with the EU, however, never took off as desired. The stinging impact of U.S. “secondary sanctions” was not the only reason. Structural obstacles also contributed. Many heavily promoted bilateral projects – such as the expansion of renewable energy sources, climate protection, civilian aviation, waste collection and water management – could not get off the ground because European commercial banks rightly feared a reimposition of U.S. sanctions – even before President Trump slapped them on Iran again.

It also did not help that Iran is outside the World Trade Organization (WTO) and has no bilateral trade agreement with the EU. Brussels has supported Iran’s WTO candidacy in the hope of helping it become a reliable trading partner.

While the EU may not fully adhere to the U.S. sanctions policy, its economic ties with Iran are bound to erode, since most European companies and banks do more business with the U.S. than with Iran. Consequently, they see no point in exposing themselves to President Trump’s wrath. While the EU’s support measures – including the special purpose vehicle (SPV) for barter trading with Iran – may help small and medium-sized European companies conduct business there, it is unlikely that major players with significant exposure in the U.S. will rely on them.

Supporting sanctions

With its short-term economic stake in Iran decreasing over the next few years, the EU might reconsider its policy – particularly if Tehran refuses to make concessions in such areas as the transparency of its civilian nuclear projects, the scope of its ballistic missile program and its regional military entanglements. Although the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) concluded in January 2016 that Iran had taken all the steps required to freeze its nuclear weapons program, as stipulated in the JCPOA, the U.S. government, Israel and nuclear proliferation experts have remained suspicious that Iran may continue it secretly.

Until now, European diplomacy has favored decoupling nuclear issues from other Iranian military activities.

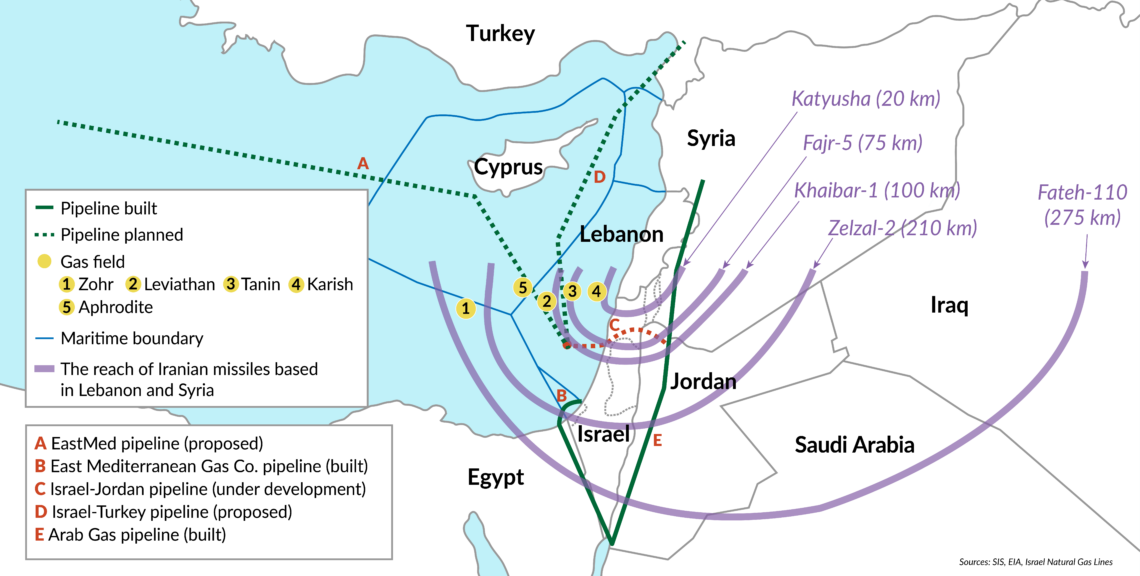

Regional security concerns have also grown as Tehran continues its efforts to create a strategic land bridge across Iraq and Syria into Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea. The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and Hezbollah, Iran’s proxy force in Lebanon, have stockpiled some 130,000 rockets and missiles to threaten Israel. They have also constructed underground weapons factories along this strategic land route. In the summer of 2016, an estimated 70,000 Iran-supported mercenaries (including many Afghan refugees from Iran) were active in Syria, and many more in 13 other countries. Iranian expenditures on military activities in Syria alone are estimated at up to $100 billion over the past six years. The intrusion of an Iranian-controlled drone into Israeli airspace in February 2018 confirmed for the Israeli government that Iran’s military capabilities pose a growing threat to national security. This could lead to a direct military confrontation.

Facts & figures

Iranian missiles' reach

The EU seems to have overlooked or marginalized the importance of those nonnuclear strategic factors and how they weigh on regional security assessments being made by Israel and the U.S. Brussels may also be ignoring the threat that Iran poses to the newly built offshore and onshore gas installations in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. These facilities include EU-supported gas export projects from Israel to Europe (via the planned EastMed pipeline and LNG tankers). Until now, European diplomacy has favored decoupling nuclear issues from other Iranian military activities in the region, whereas the U.S. and Israel increasingly regard them as linked.

If no Iranian concessions occur in the months ahead, the EU may find itself hard-pressed to reassess its policies, especially in the light of Iran’s strategic aim to become a significant player in the global oil and gas market. Achieving this goal would grant Tehran the hard currency it needs to modernize the country’s economy, strengthen its military and further enhance its geopolitical footprint in the Middle East. What stands in the way of this strategy, aside from Mr. Trump’s policies, is Iran’s support of regional terrorism as well as geopolitical conflicts with the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. These factors discourage foreign investment, which, in turn, delays the desired expansion of the oil and gas output.

Finally, the EU could be forced to take sides against Iran as Tehran’s and Riyadh’s proxy clashes in Yemen and Syria increase, destabilizing the entire region.

Iran seeks new partners

Whether or not the EU keeps supporting the JCPOA, its declining trade with Iran may encourage Tehran to keep looking east, strengthening its ties with Russia, China and India. Iran already plays a prominent role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which focuses on supplies of energy and raw materials as well as transnational connectivity. For Iran, oil exports to Asia and China are a matter of economic survival, while Russia is the most important investment partner in its expanding gas sector.

Oil accounts for some 63 percent of Iran’s exports and less than 50 percent of its budget revenues, making it less dependent on commodity sales than most other Gulf countries. The picture is even more striking in terms of income: Iran earns a mere $850 per capita from oil exports, compared with $10,800 for Saudi Arabia.

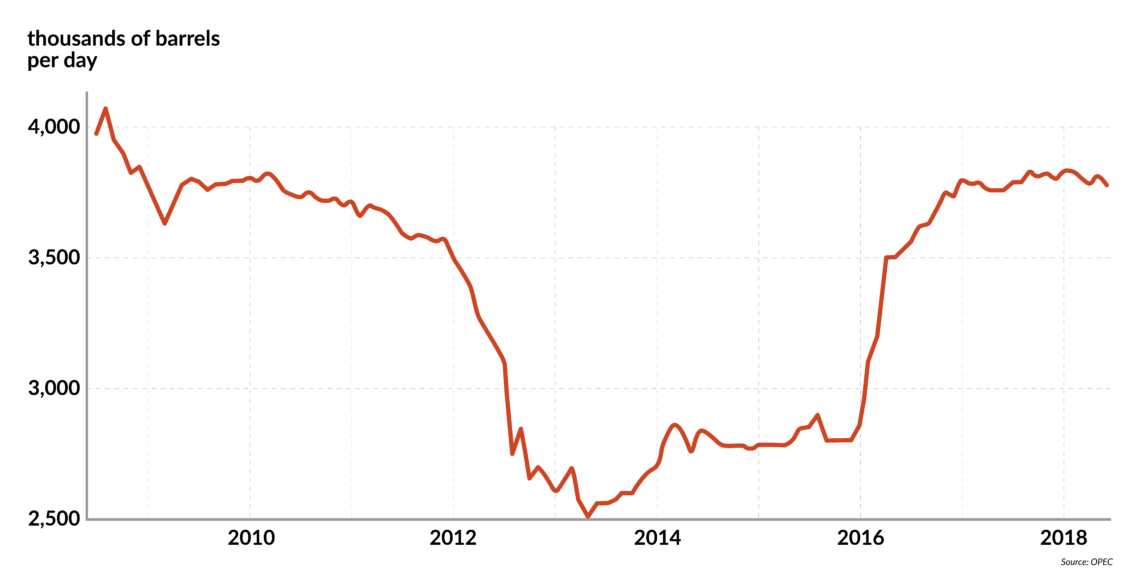

The Iran nuclear deal of 2015 opened the way for Western investment in Iran’s oil and gas sectors. Crude oil production increased from 3 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2014 to almost 4 mb/d by the beginning of 2017. In the first half of 2018, the country exported up to 2.4 mb/d. Presently, however, Iran is relying on mature fields characterized by high production decline rates (of 8-11 percent per year) and low oil recovery rates (of 20-25 percent). About 70 percent of its oil production is from the fields exploited for 50 years or longer.

Iran hopes to significantly increase its oil and especially gas exports to Europe and Asia.

Some 40 percent of Iran’s 187 existing fields and discoveries have yet to be developed. Between 2007 and 2015, the country did not bring a single new oil field on stream. Its reliance of gas injection into older oil fields is costly – as much as 12.4 percent of Iran’s entire gas production used up by this extraction-enhancing technology. This practice, along with the rising domestic gas consumption, has limited Iran’s gas exports. More than 50 percent of its gas output is already consumed by Iran’s household, commercial and small business sectors. The petrochemical industry consumes 14 percent.

Facts & figures

Iran's oil output flattens

Hence the importance of Tehran’s 2017 talks with state-owned Russian and Chinese oil and gas companies to develop 27 oil and gas projects for its upstream and downstream sectors. The combined value of these investment deals is estimated at $200 billion. Iran hopes to significantly increase its oil and especially gas exports to Europe and Asia. It also wants to make itself into a regional transportation hub for Caspian and Central Asian energy exporters.

The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA seriously complicates these plans. American secondary sanctions have already made it difficult for Iran to revitalize its hydrocarbons industry. Oil exports have fallen from 2.4 mb/d in the first half of 2018 to a mere 800,000 barrels a day (b/d) in November 2018. They could easily drop to 500,000 b/d, a level that threatens to undermine the country’s economic and political stability.

Tehran may assume that Beijing’s 25 percent tax on U.S. oil imports – a retaliatory measure in the context of the U.S.-Chinese trade conflict – makes China more dependent on Iranian supplies. This reasoning is sound because Beijing needs to limit its energy dependence on the U.S.

Since 2016, Iran signed numerous investment contracts with China as part of the BRI program. The agreements have made China Iran’s largest oil customer, with an average take of 623,000 b/d. This, incidentally, explains China’s strategic interest in securing the Strait of Hormuz, through which 30-35 percent of the global maritime oil trade flows, including liquified natural gas (LNG) tankers from Qatar, the world’s largest LNG exporter. Beijing was alarmed when senior commanders of Iran’s IRGC threatened to close the strait in response to the new U.S. sanctions.

Iran’s deepening economic ties with Russia do not yet amount to a geopolitical alliance. The two sides signed an agreement on “strategic cooperation on the energy sector” in November 2017, with an estimated value of up to $30 billion. Disregarding U.S. sanctions, Moscow supports Iranian oil sales to third countries under a bilateral oil-for-goods deal signed in 2014. This agreement even allows for an increase in Iranian oil exports. Simultaneously, however, Russia has tightened its collaboration with Saudi Arabia (as part of OPEC+) and improved its relations with Israel – even to the point of tolerating Israeli air strikes against Iran-supported militias in Syria.

Iran’s attractiveness as an economic partner fades as its economic problems worsen.

Given this, Tehran cannot completely disregard the EU in its economic and political calculations. Yet the EU’s strategic influence on Iranian policies has diminished with the onset of the full American sanctions regime. Now more than ever, Iran is reduced to relying upon lifelines from Russia and China.

Scenarios

The renewed conflict between Iran and the U.S. has opened more investment opportunities for Russia and China. Russia has pledged to boost its investments in Iran’s oil and gas sectors to $50 billion. Moscow is also interested in discouraging Iranian plans to export gas to Europe via pipelines or as LNG. Even so, both Russia and China face limits on what they can do to shore up Iran’s position, given their own ambivalent and conflictual relationships with the U.S. Moscow, in particular, must calibrate its policies to avoid antagonizing Saudi Arabia and Israel.

For the EU, the outlook is even murkier. Its member states reap little benefit from aligning themselves with Russia and China on the Iran sanctions issue. European companies have plenty to lose if they are sanctioned in the U.S. Iran’s attractiveness as an economic partner may also fade as its economic problems worsen, which seems probable as oil prices may stabilize in a lower band of $50-$65 per barrel in 2019.

U.S. sanctions seem to have weakened Iran’s reformers and strengthened principalist forces, especially the Revolutionary Guards. The country’s military leaders had always opposed the nuclear deal of 2015, favoring a harder line toward the West. Then as now, they regard the EU as a geopolitical actor of no consequence.