The European Union’s LNG supply security

The EU is shifting toward LNG as a response to decreased Russian imports, but the strategy comes with a new set of challenges.

In a nutshell

- Amid Russian gas cuts, the EU has turned to LNG

- Germany is drastically increasing its import capacity

- More LNG imports will clash with the EU’s green strategy

Shortly before the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Germany had already stopped the certification process of the Russian-German gas pipeline Nord Stream 2. Once the war began the German government decided to halt the proceedings entirely. Berlin has also agreed to end all Russian gas imports by the end of 2024.

The European Union aims to stop importing Russian fossil fuels by 2027. In 2021, Russia exported 155 billion cubic meters (bcm) of pipeline gas and around 15 bcm of LNG to Europe – around 40 percent of the EU’s 338 bcm gas imports. In 2022, Russia began to reduce its gas supplies to Europe after Western sanctions were imposed. By the end of August last year, Gazprom had stopped all gas supplies via Nord Stream 1 for Germany’s annual gas demand of 82 bcm in 2022.

Finding new suppliers after the invasion of Ukraine

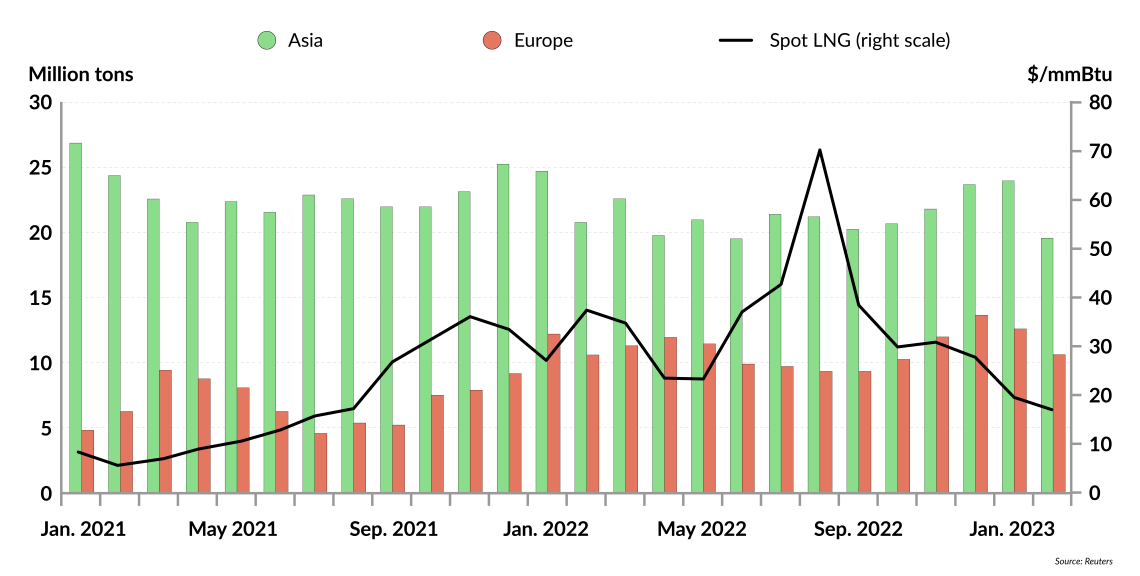

The EU was forced to take several actions in response. These included increasing renewable energy, improving energy conservation and efficiency, and substituting natural gas for coal or oil in industries and power plants. The EU-27 gas demand dropped 19.2 percent from August 2022 to January 2023, more than its official goal of 15 percent. But the EU’s LNG imports increased by 70 percent (55 bcm) to 132 bcm in 2022, making it the world’s leading importer.

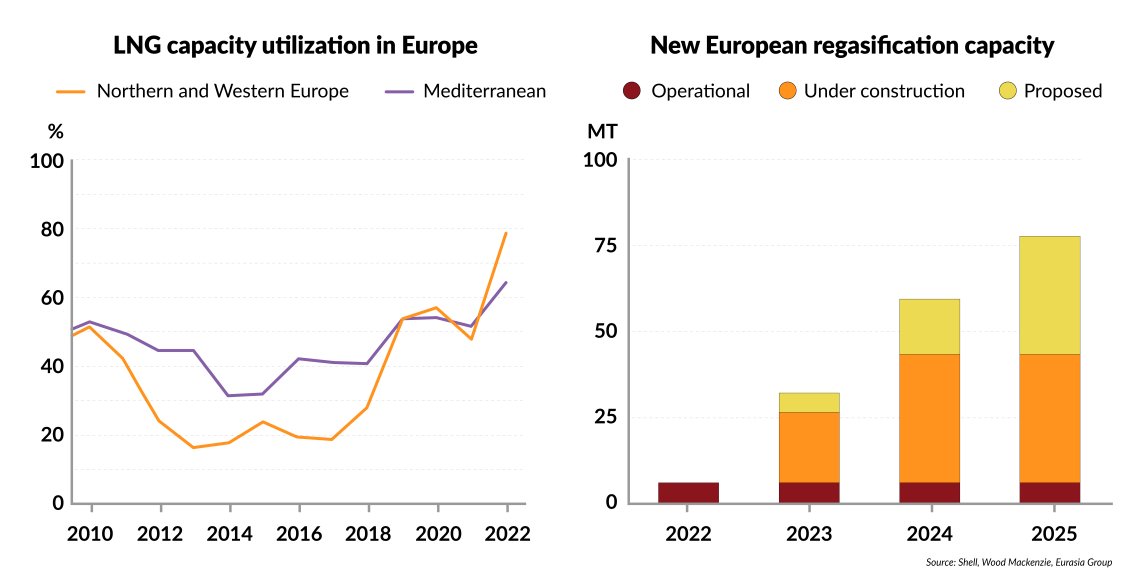

In 2021, the EU had 29 large-scale LNG import terminals with an annual capacity of 237 bcm. In 2022, Germany enacted the LNG Acceleration Act. This led to the leasing of six floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) and construction of three onshore LNG import terminals on the coast, though the final investment decision has not been made yet.

Facts & figures

Europe’s LNG boom

Three terminals in Wilhelmshaven, Lubmin and Brunsbuettel started operating, with a combined capacity of 13.5 bcm/year. Additionally, three more FSRUs will become operational by the end of this year.

In 2024, Germany will have an annual LNG import capacity of 37 bcm, expected to rise to 54 bcm by 2027 or up to 71 bcm if three FSRUs continue to operate in Brunsbuettel, Stade and Lubmin. At the same time, the EU’s gas production has been declining. Europe’s largest gas field – Groningen in the Netherlands – will shut down production later this year. Norway’s gas exports have been forecasted to decline slightly after 2027.

Other EU member states are also expanding their LNG import capacities. Those additions have been criticized by environmental organizations. In their view, these new import capacities are oversized considering Europe’s gas supply, and risk being underused and turned into stranded assets. One particular concern is that the EU’s 2022 RePowerEU plan foresees a reduction of gas consumption by 40 percent by 2030.

The EU’s quest for gas supply security clashes with its climate goals. European gas experts and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have repeatedly warned that the winter of 2023-2024 may be even more challenging than the last without Russian pipeline gas to guarantee its gas supply security and avoid any larger gas supply disruptions for its industries and households. The IEA estimates the potential gas-supply demand gap to be 40 bcm for this year. Moreover, European gas prices are still seven times higher than in the U.S., and its electricity prices are three times higher than in China. These elevated prices are undermining the EU’s global industrial competitiveness.

Facts & figures

Asia and Europe LNG imports

Factors determining LNG demand

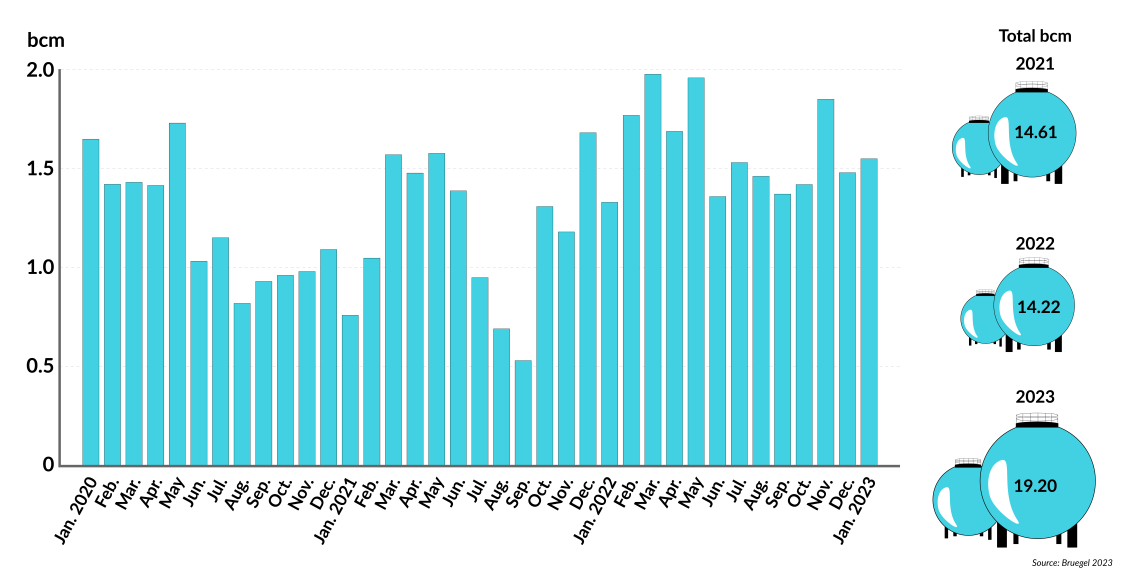

The EU has managed to withstand Russia’s weaponization of Europe’s energy dependence. Gas and electricity prices have significantly fallen but remain high by historical standards. LNG imports have been secured during the winter, and gas storage capacities are still high – presently almost 64 percent. As a result, the EU will not have to replenish its storage capacities as much as was previously feared.

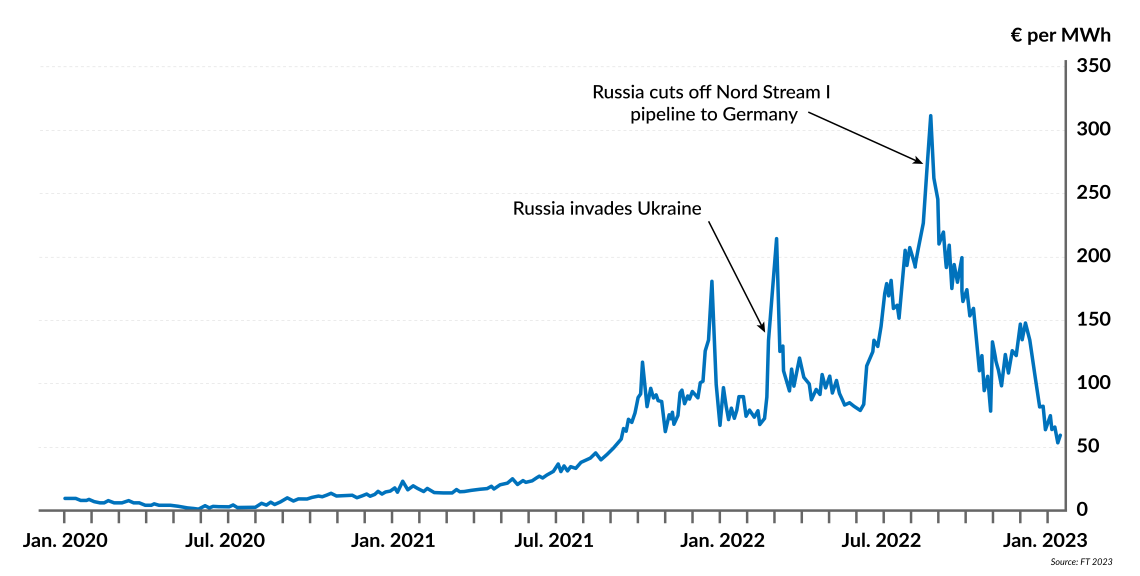

At the beginning of 2023, European natural gas prices were down by more than 75 percent from their peak in August 2022, when average spot prices were six times higher than the previous historical high. In 2023, the U.S. will replace Russia as Europe’s largest gas supplier. Globally, the U.S. will also replace Qatar as the world’s largest LNG exporter.

Overall, the situation has been improving, much to the disappointment of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin had hoped for a Europe-wide energy crisis to hamstring the West’s support for Ukraine.

Facts & figures

EU’s LNG imports from Russia highest in three years

However, Russian LNG exports to Europe actually increased after sanctions were imposed, leading many to question the political credibility of the EU’s measures.

In 2022, Russia exported 20.2 bcm to Europe, compared to 18 bcm in 2021 (a 12 percent increase) and became the third-largest LNG supplier of Europe.

Still, Russia’s share of EU gas imports fell from 40 percent to under 10 percent last year, and by 2030, its share of global oil and gas trade could be cut in half. However, the EU’s countermeasures have been costly, with an estimated 800 billion euros spent on dealing with reduced business activity and increased energy poverty. The REPowerEU plan to reduce carbon emissions and eliminate Russian fossil fuel imports by 2027 will cost 300 billion euros. Germany has spent the most on energy measures, nearly 270 billion euros, surpassing all other EU countries.

Facts & figures

Natural gas prices

In 2022, the U.S., Qatar, and African exporters redirected supplies to Europe. However, new LNG import capacities will be limited until 2025, after which new export capacities may balance supply and demand and lower prices.

The EU also benefited from China’s 21 percent reduction in LNG imports last year (about 20 bcm) due to high LNG prices and a preference for cheaper coal. China’s LNG demand is a wild card in the global market, varying by up to 40 bcm. More Chinese LNG import demand would make it more difficult for the EU to secure sufficient LNG supplies in time for next winter. The IEA predicts China will absorb 80 percent of the additional 23 bcm of LNG available this year.

The EU hopes its joint gas purchasing platform, poised to launch before the summer, will facilitate demand aggregation and joint purchasing of the approximately 24 bcm of gas needed in the coming months. The mechanism could also reduce gas prices and create reliable price benchmarks.

It is important to note that Russia’s policies have affected global markets by triggering record-high LNG and electricity price shocks. While the EU has managed these soaring prices with significant economic and financial strain, many developing countries in South Asia and Africa have been unable to afford them, leading to energy shortages and disruptions.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

The broken ties between Russia and Europe are unlikely to be mended soon. Germany has decided to wean itself from all Russian fossil fuel supplies by the end of 2024. A renewal of efforts to certify Nord Stream 2 is highly unlikely, since it would require the support of the European Commission, and effectively that of other EU member states. Furthermore, neither Germany nor the EU needs the Nord Stream pipelines for their future gas supply security. They now have sufficient LNG import capacities and the EU’s green transition plan requires that gas demand decrease by 40 percent by 2030.

Supplying ‘energy islands’

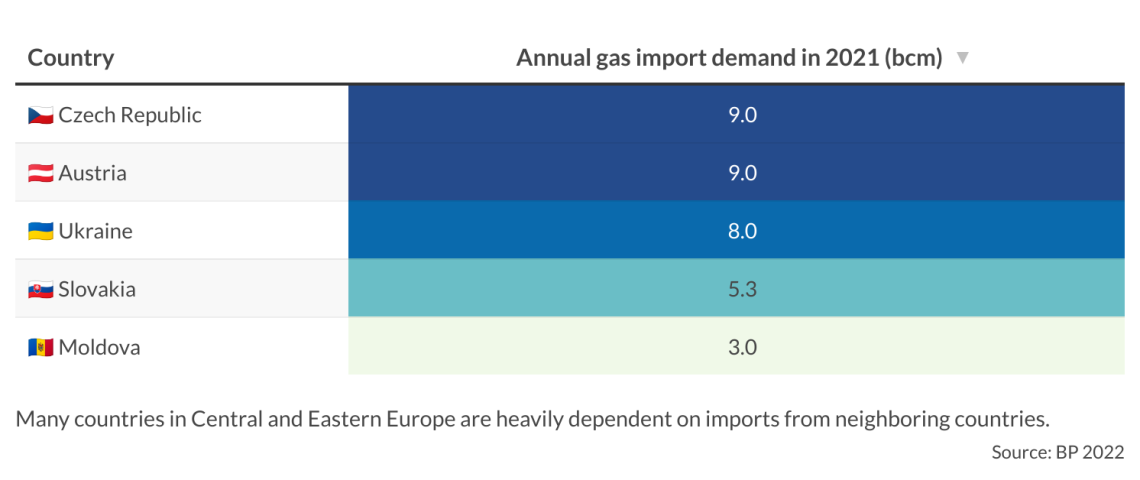

The question now is whether the existing transmission pipeline capacities from the import terminals at the coast will be sufficient to supply to individual EU countries inland. This is particularly concerning for “energy islands” like the Czech Republic, Austria and Slovakia, which had been receiving Russian gas imports via Ukraine and through Nord Stream 1.

Since 2015, Ukraine has relied on European gas imports through reverse-flow capacities at its western border, receiving about 8 bcm in 2021. Despite Gazprom's strong opposition, this supply also included some Russian gas delivered via Nord Stream 1.

Moldova, which was almost entirely dependent on Gazprom’s supplies via Ukraine until 2021, urgently needs to diversify its gas imports. The country has started importing gas from Romania and Ukraine as well. Russian gas exports to Europe through Ukraine have been reduced from the contracted 42 bcm per year to just 18 bcm in 2022, and Nord Stream 1 is no longer operational. Since last January, Russia’s gas exports via Ukraine have continued to decrease. In 2023, they will not exceed 10 bcm, amounting to only 25 bcm of Russia’s total pipeline gas to Europe this year, which includes nearly 16 bcm from TurkStream 2.

Those who claim that Germany’s LNG import capacities are excessive should keep in mind that German gas companies are under contract to supply gas to neighboring countries. These obligations did not end automatically when gas deliveries via Nord Stream 1 stopped.

Additionally, the German government is politically and legally committed to the EU’s “energy solidarity” principle. If Berlin were to fail to uphold this legal norm, the European Commission and EU member states could open a case against Germany at the Court of Justice of the European Union. Therefore, it is not enough to consider only Germany’s own gas consumption and import demand when assessing its national LNG import capacity.

The German government expects that its new LNG import terminals will have to provide at least 6-7 bcm per year to the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Moldova or even more during the cold season. The “safety buffer” required by Germany could reach 30 bcm as of 2027, especially if taking into account the potential Russian sabotage of Norwegian gas pipelines to Europe.

Turkey as a gas hub

In another scenario, Russia could use Turkey as an indirect route to supply the EU, by providing extra gas to Ankara (as the Kremlin has suggested), which would then sell it to Western countries. If this happens, Russia might be even more reluctant to relinquish its reserved capacities in Nord Stream’s Opal and Eugal pipelines, which run from Germany’s coast to the Czech Republic.

If no Russian gas flows through Ukraine, the available capacities of these pipelines may not be enough to meet the gas demands of the Czech Republic and other landlocked countries. In this situation, Germany might have to nationalize the pipelines to uphold the energy solidarity principle, ensuring the gas supply security for other EU countries and Ukraine. This would also help prevent Gazprom from exerting undue influence by controlling or restricting gas flows within Germany and neighboring countries.