Integrating a half-empty Balkans into the EU

Citizens of the Western Balkans are entering the EU much faster than their countries. As a result, the region’s depopulation is accelerating. The most desired destination is Germany, which welcomes emigrants as a much-needed supplement to its workforce.

In a nutshell

- The Western Balkans countries may soon lose up to a quarter of their population to emigration

- The region does not match the rest of Europe in living standards and governance, so people vote with their feet

- Labor-hungry Germany is happy to absorb newcomers, but the brain and workforce drain will not help the Balkans

The year 2019 will mark two decades of the Stabilization and Association Process (SAP), the European Union’s policy for integrating the Western Balkans. During that time, only Croatia managed to join the EU community – in 2013. Two other countries, Montenegro and Serbia, the most advanced in the procedure, are unlikely to make it before 2025. The rest of the pack of applicants will have to wait until 2030, at best. By that time, the region will be significantly depopulated.

People act faster than politicians and bureaucrats – with their feet. By the time the region’s integration has run its course, a large portion of its inhabitants will, most likely, already be settled elsewhere on European soil. They will not be stopped by the fact that, since 2015, immigration has become a political hot potato in the EU.

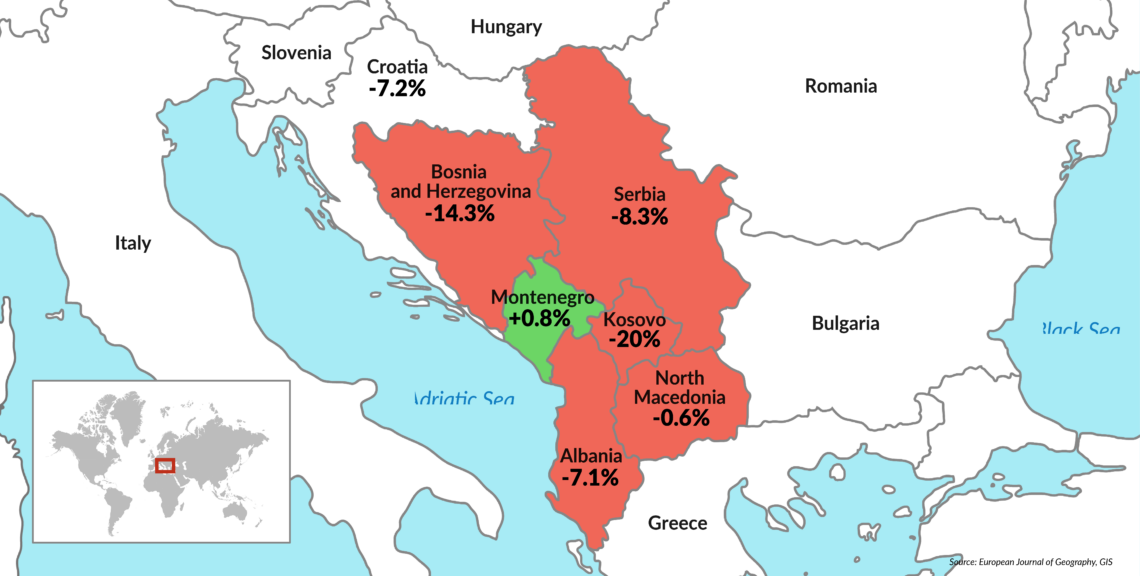

The United Nations projects that by 2050, the total population of the Western Balkans will contract from 7 percent to 23 percent. Observed trends support the higher end of this projection. By 2018, some 2.4 million people, or 15 percent of the population, had already disappeared from the region. A quarter of the Macedonians are gone, 450,000 people in 1997-2010 alone. Some 250,000 individuals departed Bosnia and Herzegovina during the last decade, according to a World Bank estimate, while Albania lost as many as 1.6 million of its citizens. The figures for Serbia, Kosovo and Montenegro are, respectively, 650,000, 67,000 and 7,000.

Poor prospects

Western Balkans migrants tend to give up citizenship of their home countries. In the last decade, some 330,000 Albanian citizens have been naturalized in the EU countries. Some 40,000 Kosovars and 7,000 Macedonians have opted for other countries’ passports in just the past three years.

This trend is likely to continue through the next decade, especially among the younger generation, creating a massive brain drain from the region. Last year, a Gallup International survey in Kosovo showed 40 percent of the participants declaring their intention to leave. The figure for Albania was 32 percent, for Northern Macedonia 30 percent and for Serbia 25 percent. Empty schools and villages are commonplace in the region, and the sight will become even more familiar in the years to come. Already in 2019, some schools had more teachers than students.

Poverty afflicts nearly 30 percent of the population.

This massive emigration has known drivers, ranging from the socioeconomic (joblessness, poor career prospects, economic insecurity) to the political (poor governance and corruption) and even criminal (extortion and human trafficking).

High unemployment remains the main reason for people leaving the Balkans. According to Albania’s Institute of Statistics (INSTAT), 84 percent of those emigrating from the country went in search of jobs. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Northern Macedonia and Kosovo have youth unemployment rates above 50 percent and overall unemployment of about 10 times the EU average. As a consequence, poverty in the region afflicts nearly 30 percent of the population.

Civil liberties shortage

Politically, the Western Balkans states are classified as “partly free countries” in the Freedom in the World 2019 report by Freedom House, which reviews the political rights and civil liberties situation globally. It puts Bosnia and Herzegovina’s aggregated score at 53 out of 100, Kosovo at 54/100, Northern Macedonia at 59/100, Montenegro at 65/100, Serbia at 67/100 and Albania at 68/100. The Economist Democracy Index 2018, in turn, grades most of the Balkan states as “hybrid regimes” with scores of between four and six on the 0-10 scale. Only Serbia makes it to the “flawed democracy” rank with a score of 6.41.

Regarding internal security, the region ranks near the middle of the pack of the 128 countries surveyed by the Global Finance Magazine. It lists Bosnia and Herzegovina as the 56th among “The World’s Safest Countries 2019.” Serbia is ranked 58th, Northern Macedonia 59th, and Albania 69th.

From an economic standpoint, the region’s performance has not been so bad. Even though gross domestic product (GDP) remains relatively low in the area, at between $4,000 and $6,000 per capita, the Heritage Foundation’s “2018 Index of Economic Freedom” places most of the Balkan countries in the top third of its ranking: Northern Macedonia comes out at 33rd, Kosovo 51st, Albania 52nd, and Serbia 69th. Montenegro lags behind at 92nd place out of 180 countries.

Underdeveloped infrastructure remains a formidable obstacle to economic growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that Balkan governments invest only about 1 percent of their countries’ GDP in infrastructure. Also, the region’s inhabitants remain heavily dependent on remittances received from family members working abroad. In 2017 alone, the Serbian diaspora sent 3.1 billion euros to Serbia. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the inflow was 2.6 billion euros, while the Kosovar diaspora sent their relatives 665 million euros, equivalent to one-third of Kosovo’s annual state budget. With Balkans emigrants providing critical sustenance to their families at home, the trend of emigration is sure to continue.

Uneradicated corruption

From the standpoint of governance, the Western Balkans continue to be one of Europe’s most corrupt regions, trailing only Russia and Ukraine. In Transparency International’s “2018 Corruption Perceptions Index,” which covers 180 of the world countries, most of the Balkan states are grouped in the middle of the ranking, between 67th (Montenegro) and 99th place (Albania).

The depopulation drama generates geopolitical risks.

The emigration challenge is multifaceted and prone to changing its character. While the Western Balkans was a “transit region” during the migration crisis of 2015-2017, today it is a place where problems originate: it has become a new base of migrant smugglers and groups engaged in human trafficking. Transnationally organized crime groups in the region control the flow of modern-day slaves and other illegal activities. The U.S. State Department has called local law enforcement in this area weak, even though registrations and prosecutions of human trafficking cases are on the rise.

Europe’s empty periphery

This year and the next will most likely bring a new exodus from the Western Balkans. It appears that the region will remain a rich source of immigrants for the EU, just as Central America is for the United States. In both cases, the trends and features are similar: authoritarian regimes, captured states, organized crime, corruption and poverty all push ordinary citizens to search for a better life elsewhere.

Balkan emigration will bring significant internal and international consequences. Shrinking populations will affect the electoral census, likely leading to discrepancies between the official and real electorate in some countries. Also, the traditionally bloated public administration in the Balkans will find itself trying to live off ever-smaller populations – another source of potential conflicts.

The depopulation drama will generate geopolitical risks as well. As Balkan immigrants supplant those from Central European states in the “old” EU, non-European immigrants will replace the native Balkan population at home. These movements will be dictated by the labor market situation in Europe.

Only two years ago, Croatia had strict restrictions on receiving people from the Western Balkans. Last year, however, it simplified procedures to open the door wide for much-needed workers. At the beginning of 2019, it issued 29,769 temporary residence permits to non-EU citizens. In the EU, Germany alone urgently needs more than a million new workers, while the four Visegrad countries have 520,000 job vacancies.

Such opportunities will continue to lure people from the Balkans north, and as they depart, new arrivals from the Middle East and Africa will fill the demographic vacuum. Last year, Albanian citizens were among the 10 most numerous groups of asylum seekers in EU, filing 21,900 applications. January 2019 INSTAT data shows a decrease in the country’s young population as compared to 2018.

This is not an isolated phenomenon, but part of a broader European trend. Waves of emigration have affected even some of the new EU member states. In the first three years after Croatia joined the EU, about 230,000 people left the country seeking employment and better conditions in Western Europe. Bulgaria and Romania experienced a similar exodus, losing about 20 percent of their populations. In the past seven years, the number of Bulgarians living in Germany increased fivefold to 416,000, according to data compiled by the Foreign Ministry in Berlin.

Germany’s shift

Such migrations have profound geopolitical and cultural implications. The emerging process of replacing indigenous Balkan population with immigrants from northern and sub-Saharan Africa will change not only the demographic characteristics of the region, but also bring the Mediterranean world closer to the heart of Europe.

Germany is likely to remain the immigrants’ most desired destination. German companies have been struggling to fill some 1.6 million vacancies, according to the country’s Chamber of Industry and Commerce. Starting in 2020, foreigners will be employed in Germany under a modified labor law, with fewer regulatory limits and bureaucratic hassles. Anticipating this, doctors, nurses and IT specialists already have started en masse to learn German. The forces of the labor market may eventually elevate German to the status of a dominant tongue in the region, replacing English and causing a shift from the Anglo-Saxon to Germanic cultural sphere.

If this trend continues for another decade, the Western Balkans will be integrated into the EU not by the politicians, but by its people voting with their feet. But for those preoccupied with immigrants from the Middle East and Africa, the population drain from the Balkans and its longer-term consequences get little attention.

The base scenario would see heavy migration from the Balkans to Europe, especially Germany.

Surveys show very high levels of support for EU integration throughout the Balkans – ranging from 93 percent in Albania to 72 percent in Northern Macedonia – but this sentiment has not translated into domestic policies that would support the process. The region’s problems of state capture, rampant corruption and organized crime untamed by the ineffectual judiciary and public administration have been pointed out time and again in accession progress reports by the European Commission. Even so, progress has been painfully slow. That may explain the high level of opposition in EU member countries to integrating the Balkans. According to the December 2018 Eurobarometer poll, 64 percent of Finland’s citizens were against it, as compared with 62 percent in France, 61 percent in Germany and 58 percent in Austria.

Scenarios

Where does it all lead? At least two scenarios are possible.

The base scenario would see heavy migration from the Balkans to Europe, especially Germany, continuing unabated for the next decade. This would leave the region half-empty, economically enfeebled and in dire need of workers. Non-European immigrants from Africa and elsewhere would find it a dream transit location, a perfect trampoline to get into the EU. This would make it impossible for any Balkan country to join the community, as political and social fatigue with the endless integration process sets in. Rebuffed by the EU, shedding population, aging and economically stagnant, the region will become Europe’s empty periphery, a haven for migrants, and a playground for non-European actors.

Of course, it is possible to imagine a more optimistic scenario, but only to a certain degree. Under this more benign script, all Balkan states would be EU members by 2030, with their political structures overhauled and their economies stabilized. Both the EU leadership and local politicians recognize that another lost decade in the Western Balkans could produce a catastrophe. But even if things go relatively well, emigration from the area will continue. The challenge for the entire region will be to find ways to sustain economic growth while adjusting to the adverse demographic reality.