Europe and Huawei: Rising cybersecurity challenges

More than 100 times faster than 3G and 4G, the next generation of cellular technology could reshape economies and societies. Countries in Europe may face political and industrial espionage if they cooperate with Huawei in their 5G rollout.

In a nutshell

- The 5G rollout will create numerous cybersecurity risks

- EU countries are compromising between industry needs and security requirements

- Future wireless networks will be vulnerable to espionage and systemic threats

The 2020 Munich Security Conference highlighted the United States’ determination to pressure its European and Asian allies not to collaborate with China’s 5G mobile phone network provider, Huawei. Chinese involvement could increase cybersecurity risks like industrial and political espionage or sabotage.

The Trump administration has gone as far as to threaten to restrict the information it shares, even within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), to gain some leverage in the matter. While many European allies share the U.S.’s cybersecurity concerns regarding Huawei, they are unwilling to completely exclude it from their 5G deployment, instead seeking to restrict its role. But by focusing on one company, the political debate overlooks broader cybersecurity risks.

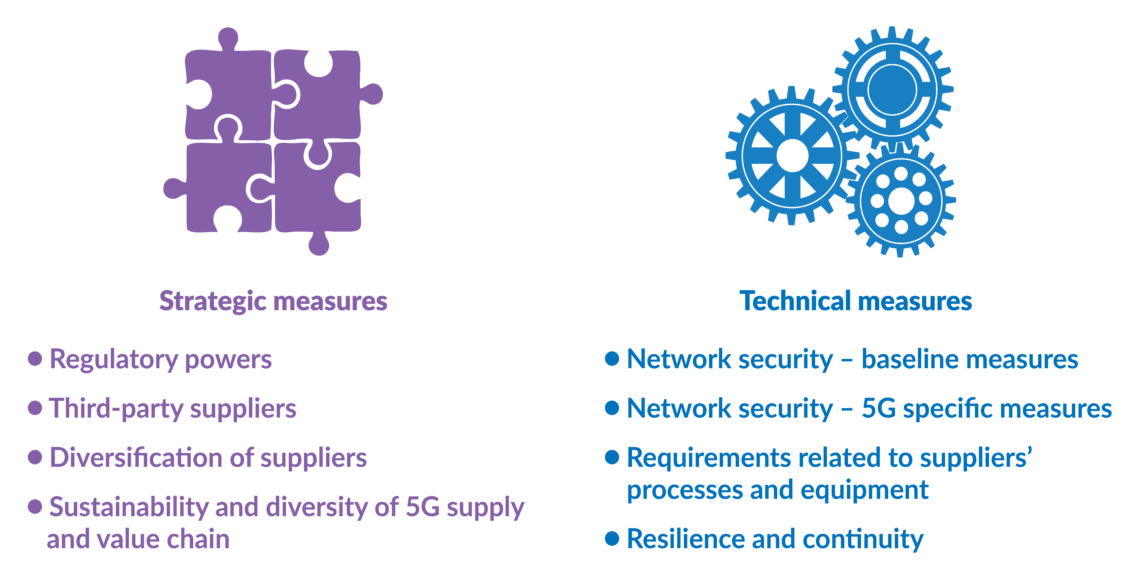

European responses

On January 28, the British government decided that Huawei would be excluded from its core 5G network and restricted to its periphery. It also imposed a lower, 35 percent market-share cap for the company in the noncore network, effective as of 2023. (The current market share stands at 44 percent but could rise up to 70 percent over the next three years.) The British Security Council and UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) have stated that, thanks to these restrictions, the risks of espionage, theft, alteration of data, blackmail and network sabotage will be reduced to “acceptable levels.”

The NCSC has admitted that the risks of using Huawei technologies in the UK’s 5G network can never be completely removed. It has also assessed that Huawei is a “high-risk” 5G contractor. The organization is especially concerned with China’s National Intelligence Law of 2017, which allows the government to “compel anyone in China to do anything.”

The NCSC has admitted that the risks of using Huawei in the UK’s 5G network can never be completely removed.

NCSC officials have also warned that Chinese state actors “have carried out and will continue to carry out cyberattacks against the UK and [its] interests.” Like many independent cyber experts, they believe Huawei’s cybersecurity and engineering is of low quality and that its processes are opaque. In a 2019 report it confirmed that the Chinese company has made “no material progress” in addressing “major defects” and significant security concerns already being raised the previous year.

Germany also needs to decide to what extent it will allow the Chinese company to enter the sector – a difficult balancing act between cybersecurity and the needs of the industry. The EU’s security guidelines are only recommendations, and it is up to member states to determine the technical sovereignty of their 5G network.

In Berlin, the Chancellor’s office and the Ministry for Economic Affairs, along with many parliamentarians, resisted a Huawei ban. After much controversy, a compromise was agreed upon in February. Any “untrustworthy” companies (Huawei is not mentioned by name) that do not meet the government’s security catalog requirements can be excluded or restricted from Germany’s 5G rollout.

“Monocultures,” meaning excessive reliance on only one network supplier, should be avoided. Authorities can ban the use of components from a network provider if they are believed to pose a security threat. Minister for Economic Affairs Peter Altmaier has promised the highest possible security standards not only for the core network, but also for transport and access systems.

Although the German compromise paper does not refer to the EU’s security recommendations for 5G, parliamentarians have started to refer to the strict security criteria of the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA).

At the end of 2019, the U.S. government reportedly gave the German Foreign Ministry proof of Huawei’s collaboration with Chinese security agencies. The Germany Foreign Intelligence Service (BND) had already warned against including Huawei in the 5G rollout in January 2019. Even the Federation of German Industries is against the company’s participation if no sufficient security guarantees can be provided.

The U.S. also provided evidence to Germany and the UK that Huawei had been inserting backdoors for law enforcement use of sensitive and personal information into 4G equipment since 2009 – a practice which the company denied in official statements.

Meanwhile, Orange, the largest French telecommunication company, opted for Nokia and Ericsson instead of Huawei for the deployment of its 5G network in mainland France.

Restricting Huawei’s participation would require dismantling some of the company’s technology, which could be costly.

Overall, despite being aware of the risks of including Huawei in their 5G rollout, European countries will face significant technical challenges in doing so. Private Western telecommunication companies are already cooperating with the Chinese company to operate the current 3G/4G wireless network. The deployment of 5G will be built upon the existing system. Restricting Huawei’s participation would require dismantling some of the company’s technology, which could be extremely costly.

Despite its criticism of Huawei, the U.S. offers no alternative since no American company could deploy the technology. Only Nokia from Finland, Ericsson from Sweden and Samsung from South Korea could offer 5G networks. U.S. Attorney General William Barr recently suggested taking a majority ownership stake in Nokia and Ericsson, but the Trump government then denied considering such action. Furthermore, the EU’s growing economic dependence on China means all European governments fear repercussions in their bilateral trade relations if they anger Beijing.

By the end of February 2020 Huawei had already won 47 commercial 5G contracts in Europe, in addition to 27 in Asia and 17 in the rest of the world. With 91 contracts in total, the Chinese company is ahead of Ericsson and Nokia, who have 81 and 63 respectively.

Facts & figures

Additional challenges

Disruption by Huawei is not the only threat facing European 5G deployments. EU member states will also have to cope with rising systemic cybersecurity challenges:

- Industry 4.0. National 5G mobile networks will connect future networks of critical infrastructure (CI) and Industry 4.0 with millions of potentially unsafe appliances on the Internet of Things – 75 billion of which are expected to exist by 2025. With every additional connection, it will become harder to identify vulnerabilities in the system, despite efforts to enhance encryption, authentication, privacy, integrity protection and overall network resilience.

- Proprietary information. The various hardware, software application, protocol and code layers needed for 5G include proprietary information, which makes it almost impossible to supervise network messages between the hardware and end consumers.

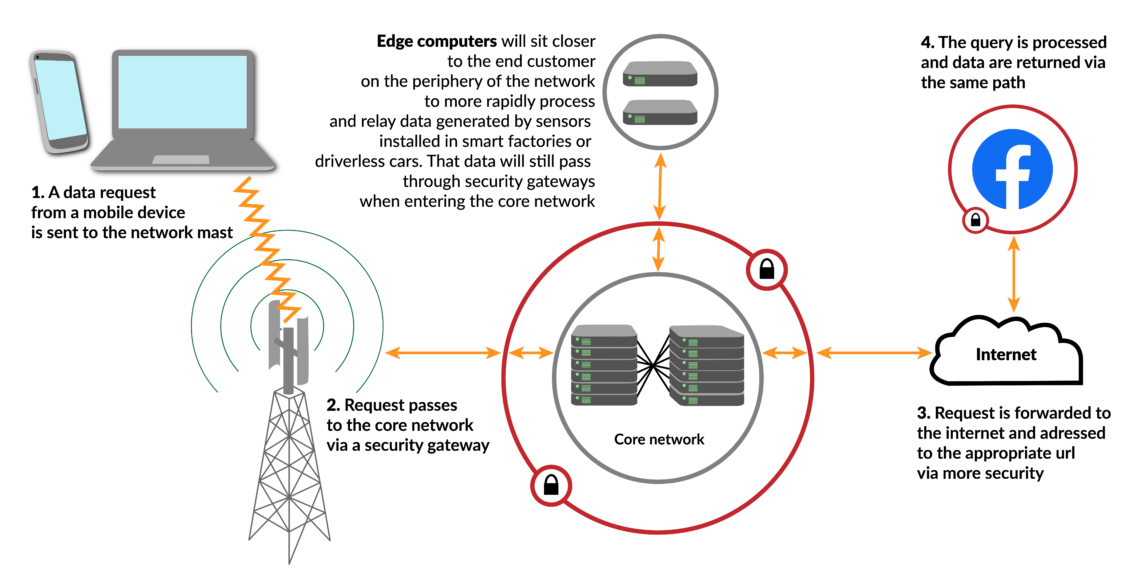

- Expanding core. In contrast to earlier 3G/4G technology, the traditionally-defined “core” (where customer information is stored and processed) of the 5G network will not be clearly separated from the periphery – meaning antennas and base stations, including those from Huawei. More computing power, clouds, servers and processes will move from the core to the periphery since numerous Industry 4.0 appliances require more decentralization.

- Expanding software. The distinction between hardware and software will blur as networks become increasingly virtual. More than ever, design will rely on software in dynamically configured hardware.

- 4G vulnerabilities. The 5G network technologies will be entangled with the older 3G/4G structures, which means they will inherit existing vulnerabilities.

- Lax security. Many Western network operators have been lax about security so far, and they could continue down that path. Several mandatory security features, as defined by international and national standard security committees, have not been implemented due to perceived costs.

- Opaque source. Cybersecurity experts believe the source and program codes for 5G networks should be disclosed, but commercial actors are unlikely to comply. Even if they did, network operating companies like Huawei can change program codes via remote control and maintenance operations.

- Software updates. Automated software updates also pose a challenge – they sometimes contain security flaws called “bugdoors,” which cannot be detected in time when installation is automatic.

- Scale of surveillance. The 5G networks will increase the scale of attack surfaces to such an extent that traditional monitoring methods will become ineffective. Managing the risks of a potential “untrustworthy” vendor could even overwhelm all national resources. This is particularly true for countries that do not have the institutional capacity to survey and control the unprecedented complexity of 5G network operations.

Beijing’s plans

Huawei’s 5G policies perfectly exemplify how China plans long term by investing in future disruptive technologies and their industry applications. Huawei has become the world’s largest 5G network provider thanks to generous government subsidies. As Huawei technology is still hardware-centric, it is often deliberately kept incompatible with products from rival brands, and its interfaces cannot be used with most other vendors’ goods. As a result, technological path dependencies develop over several generations of products. (While Western telecommunication companies are also trying to restrict compatibility between brands, they often compromise because of consumer preferences and regulatory requirements.)

Creating technology path dependencies is another element of China’s supply- and value-chain strategy, which seeks to control worldwide research and development, critical raw materials and end products in future key technology sectors.

In all likelihood, the majority of EU member states will try to restrict Huawei to the periphery network.

Many new systemic cybersecurity risks result from the globalization and privatization of the telecommunication sectors. The latter have forced private telecommunication companies to prioritize costs, prices and commercial profits over security and government interests. As long as cybersecurity investments are considered a liability rather than a competitive advantage, the EU’s critical infrastructure, including mobility networks, is unlikely to improve on the security front.

Scenarios

Given these lessons, the EU might decide to support 6G research in order to reduce its technology dependence and eventually help European companies supply a 6G network throughout the continent. This would also allow the EU and the cybersecurity committees of its member states to incorporate new security standards into the design of 6G networks from the outset. Otherwise, countries will have to retrofit these measures after the development of the technology – a solution that is far from optimal.

In all likelihood, the majority of EU member states will not ban Huawei altogether, but they will try to restrict it to the periphery network in one way or another. But restricting Huawei’s technologies to the periphery will not solve many fundamental cybersecurity challenges. The traditional differentiation between the core and noncore periphery is no longer possible, nor is the distinction between the hardware and software adequate for virtualized networks. Moreover, the UK, Germany and a few other EU member states have the capacity to define and maintain “acceptable levels” of cybersecurity risks. But other EU member states have no institutionalized cybersecurity risk culture, expertise or capacities and will therefore struggle to implement comparably rigorous risk mitigation strategies.