Asylum seekers versus economic migrants

European governments are torn between the moral case for welcoming refugees and the impracticality of universal compassion.

In a nutshell

- Migrant flows have tested European cohesion

- The right to claim asylum is being reconsidered

- Existing policies are delaying hard decisions

The past decade has seen repeated tragedies of migrants from Africa drowning while attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea. More recently, such episodes have also played out in the English Channel, as migrants seek to transit from France. The horrid nature of these events has energized activist groups and tested the internal cohesion of the European Union.

Concerned governments are faced with a dilemma, in that managing increasing migrant flows pitches morality against practicality. It is hard to deny that rich countries have a moral responsibility to help those in need. That imperative becomes acute when migrants seeking a better life are drowning before our very eyes. And it becomes insufferable when women and children are involved.

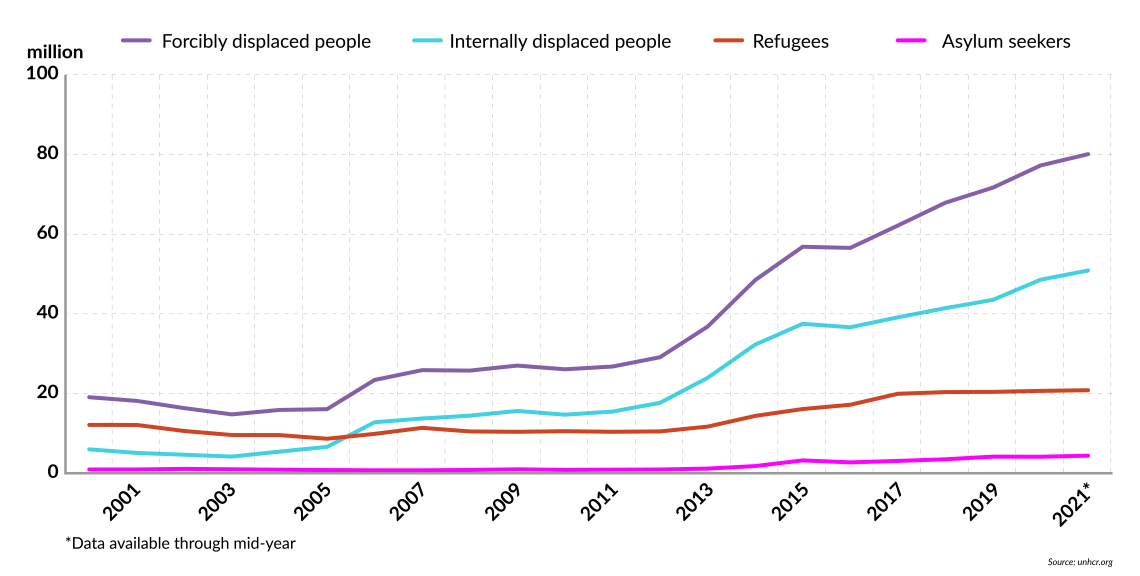

Yet, it is equally hard to deny that the sheer numbers involved make universal compassion practically impossible. By the end of 2020, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, there were 82.4 million forcibly displaced people in the world, more than a quarter of whom were categorized as refugees. Having doubled since 2010, this number is now higher than ever, and is sure to keep increasing.

At the core of the dilemma lies the right to claim asylum. This right was codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The key problem with this noble stance of compassion is that present-day realities have fundamentally changed over the past eight decades.

Economic logic

The right to claim asylum was originally based on the presumption that, once a refugee had managed to cross a border into a safe country, their journey would be over. It was never intended to cover cases in which migrants crossed numerous borders in search of a better life – transiting through perfectly safe havens to countries like Germany or Sweden, where benefits are generous, or the United Kingdom, where job opportunities are better.

Those who believe that the problem of mass migration will subside with rising economic welfare in some of the most impoverished African states must think again. In fact, the poorest individuals cannot even afford to leave their own villages; as these communities become wealthier, households are increasingly able to opt for migration to better their conditions. By pooling resources, it becomes possible to send one family member – preferably a strong, young male – on a trek to Europe.

The implication of this argument is that the short-term impact of economic development in poor countries is likely to increase, rather than decrease, the flow of migrants. This also highlights the inherent complexity of moral arguments that underpin pleas for more “humane,” welcoming immigration policies. Such campaigns are simply bound to enhance the attraction of migrating to where such policies are adopted. The nature of the tension between morality and practicality may be brought out in three fundamental principles.

Facts & figures

Forcibly displaced people worldwide, 2001-2021

The first is that help from the rich to the poor must benefit the neediest first. Even a casual glance at imagery from migrant flows will show that this has not been the case. These routes present a massive overrepresentation of strong, young men. Most have left women, children, and parents behind, and few have grounds to claim asylum.

The second is that the scope for criminals to profit from the plight of poor people must be constrained. Bolstered by the promise of asylum, human trafficking has developed into an increasingly sophisticated industry, rivaling the drug trade. Its appeal is determined by the rate of profit in relation to the risk of apprehension and the severity of punishment.

The third is to maintain the integrity of national borders. The opening of the sluice gates in 2015 dealt a severe blow to existing rules and regulations, like the Schengen and Dublin Agreements. As borders were thrown open, the EU was overwhelmed by internal conflicts that have made the restoration of order exceedingly difficult.

Future developments can move in three very different directions. One is a radical departure that sees broad agreement among governments to abolish the right to claim asylum. Another is a reaffirmation that the right to seek asylum trumps practical considerations of how many migrants may be absorbed and integrated. The third is business as usual.

Scenarios

Restraining the asylum right

The radical departure scenario would go a long way toward meeting the three fundamental principles outlined above. Abolishing the right to enter any country of choice simply by uttering the word “asylum” would produce several immediate effects. It would undermine the business model of human traffickers, and reinforce national borders. It would also enable governments to reallocate huge resources – from processing large numbers of economic migrants with no grounds to claim asylum to helping those left behind in poor countries.

The essence of this scenario is an approach to international migration that is based on a combination of cost-effectiveness and genuine morality. The resources now devoted to processing and supporting a single migrant who has arrived without documentation and cannot be repatriated would no doubt suffice to support a number of poor people in their country of origin. Channeling these resources into refugee camps would allow the promotion of small-scale, low-skilled jobs that are suited to those who need them.

It is hard to see the morality of the alternative – of allowing large numbers of low-skilled migrants into societies where most will never be able to find gainful employment; where children, who under other circumstances would have genuine opportunities, grow up in the shadow of parents mired in permanent unemployment; and where too many families will remain stuck in parallel societies that are rife with crime and religious radicalization.

The fact that this latter alternative is what has come from much of the mobilization for compassion illustrates the self-serving nature of morality among many activist groups. Perhaps helping one young man who has arrived without documentation and will likely never be able to support himself – far less his dependents left behind – provides a larger ego boost than using the same funds to help anonymous, faraway women and children.

But what makes the radical departure scenario difficult to even discuss is that it would trigger an intense mobilization of moral objections. The fact that the right to claim asylum has been included in the catalog of internationally recognized human rights means that to even hint at a need to amend or abolish it would energize advocacy groups into massive protests.

Compassion first

While the second scenario, a firm commitment to universal compassion, would go a long way toward satisfying those who plead for more “humane” policies, it would also present serious complications. Most importantly, on the grounds of genuine morality – defined as the maximum good for the maximum number – such an approach would be counterproductive.

The logical consequence of upholding a universal right to claim asylum must be to introduce a regime of open borders, and to provide secure routes for legal travel to destinations of choice. This would undermine the nation state as the pillar of the global economic and political order. And as the nation state is eroded, it will become increasingly complicated to raise taxes in a legal and organized manner, one based on the rule of law and accountability.

The latter, in turn, would erode the provision of important public goods, as those with resources look for privatized solutions to security and healthcare. Even the protection of human rights, which is at the core of the humane position, would be undermined. Without well-ordered nation states that act together for a common purpose, international treaties on human rights would not carry much weight.

Although the opening of borders to all who wish to claim asylum would not bring about immediate collapse, there would be an accelerating erosion. National authorities would have to face the fact that even if undocumented migrants are detected, those who are refused asylum cannot be repatriated. Compassion would then require that they be provided for; the precedent has already been set.

In some countries, illegal migrants enjoy rights to healthcare and their children have a right to education. Meanwhile, social services are prohibited from informing the police about the presence of illegal migrants, even in cases where they may have committed crimes and been subjected to lawful deportation orders.

While this scenario must be considered extremely unlikely to materialize, it does shed light on the stakes of pleas for more “humane” approaches to migration.

Business as usual

The likeliest scenario is that of the middle ground: failing to make a clean break with asylum as a human right while continuing to make it as hard as possible for migrants to arrive in a position where they may claim that right. Means to achieve the latter have ranged from restricting the number of places where refugees may legally file applications for visas, to tacitly allowing the use of force by border police and coast guard units to prevent migrants from even approaching borders, known as “push-backs.” The effect in all such cases is to undermine legality and the rule of law.

The essence of this scenario is that it constitutes little more than a delay tactic. The inherent contradiction between morality and practicality may be mitigated by a variety of halfway measures, such as the introduction of asylum processing centers in countries outside Europe and applying pressure on poor countries to accept migrants in return. But the fact that such measures will merely attenuate rather than resolve the conflict implies that the thrust will be the same as under the universal compassion approach.

As the flow of international migrants continues to increase, retaining the asylum right will produce three sets of negative consequences. It will play into the hands of human traffickers, who will be sure to come up with diversified “services” that are adapted to overcome whatever obstacles national authorities manage to put up. It will embolden governments like Turkey and, more recently, Belarus, which have found ways of “weaponizing” migration to extort bribes and concessions. And it will undermine the rule of law in countries of destination, as officials are tempted into selling necessary documents, ranging from visas and false age certificates to residence permits.

Perhaps the most important message of this most likely scenario is that it shines an unforgiving light on the moral implications of encouraging poor people to take huge risks in the hopes of winning asylum. Young men who do manage to get into Europe but fail to secure employment allowing them to send money back home represent a tragedy – not only for those left behind but, in many cases, also for the migrants themselves. In the longer term, the accelerating flow of illegitimate asylum seekers is also bound to stoke negative sentiment toward genuine refugees who are in dire need of international assistance.