Europe’s battery strategy

Europe is on a mission to increase its battery production by establishing a foundation for large-scale supply chains on the continent. It is a tricky proposition, not least because it is an expensive plan to carry out and China already holds the dominant position.

In a nutshell

- Europe is making a big push for the production of EV batteries

- The changes could alter trade routes and geopolitical alliances

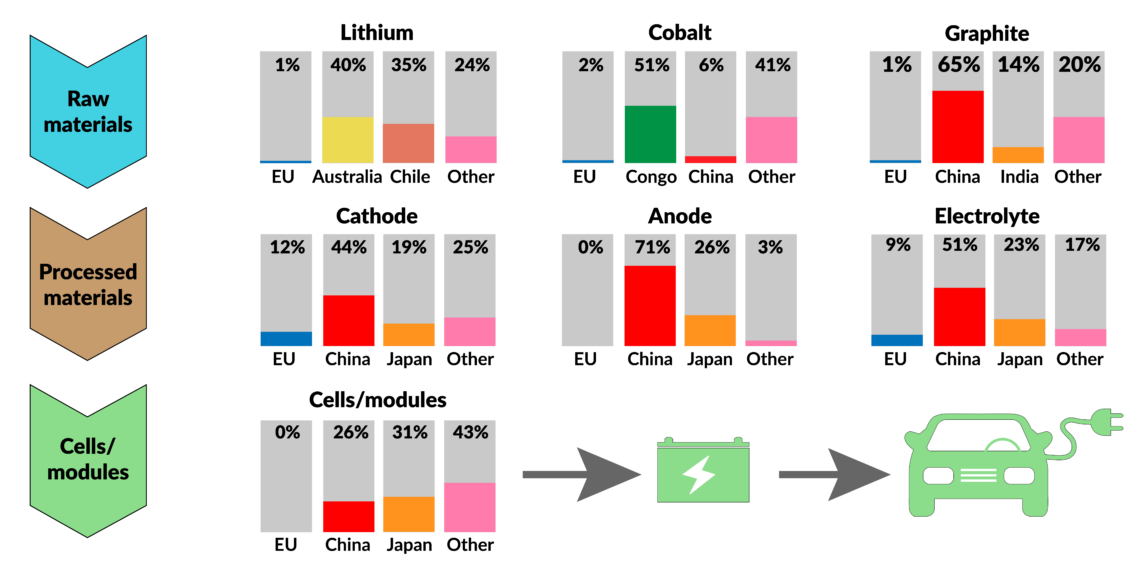

- China still has huge advantages in processing and raw materials

Since the European Union launched its European Battery Alliance in 2017, the bloc has been trying to catch up with China, South Korea, Japan and the United States in manufacturing batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and other applications. The EU industrial policy seeks to build an entire battery value chain throughout the continent, allowing Europe to compete with these global rivals.

Battery-technology development, production of batteries and costs thereof are driven by the EV market in Europe. But building up a European battery supply chain will also hinge on the structure of the market and the stability of the grid, factors which themselves will require large-scale investment. Moreover, the new trade routes and strategic partnerships that develop will change the geopolitical landscape.

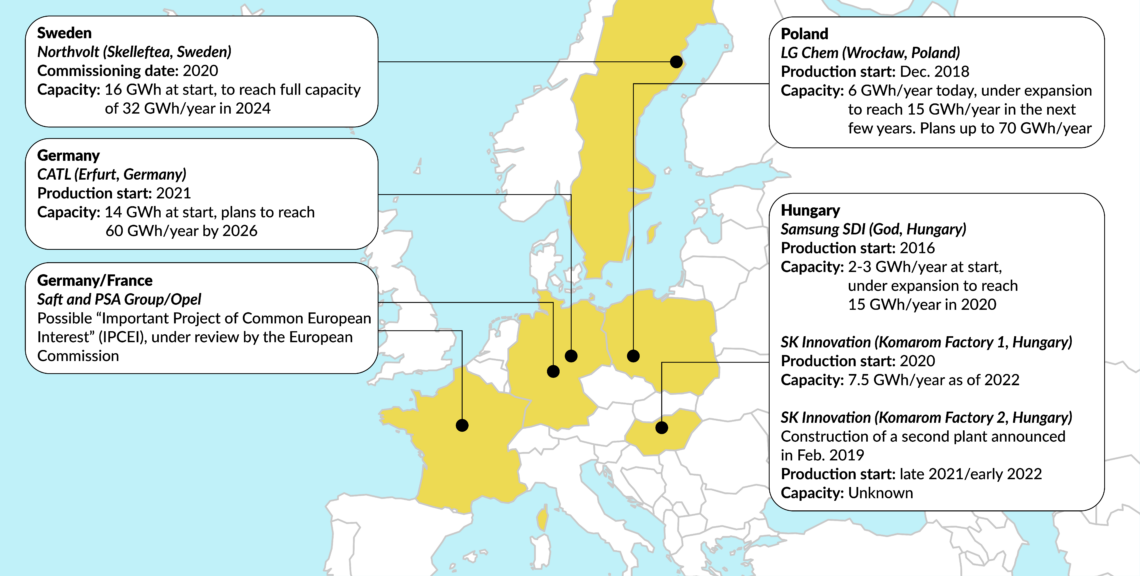

The EU aims to heavily boost the production of batteries by building 25-30 battery gigafactories (see box) across Europe with a capacity of some 400 gigawatt-hours (GWh) by 2025. By last year, around 260 industrial and innovation organizations had already joined the alliance. In 2018, the European Commission published a “Strategic Action Plan for Batteries” with 37 policy measures, including securing reliable access to critical raw materials (CRMs) and processed materials.

Facts & figures

Gigafactories

A gigafactory is a factory that will produce batteries for electric vehicles on a large scale. The word was coined by Tesla CEO Elon Musk. The word did not originate in Europe, but refers to a giant factory built by the company near Reno, Nevada, that focus on the production of such batteries.

Seven EU countries – Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Sweden – have announced funding of up to 3.2 billion euros combined for battery projects through 2031. The European Commission expects another 5 billion euros in private investment. So far, the focus has been on assembling battery packs for EVs rather than the battery cells themselves, which mostly takes place in Asia.

Varied applications

The future of battery technology goes far beyond the transportation sector. Modular battery storage systems allow a wide range of industry applications, including for power generators that rely on intermittent sources of renewable energy. Batteries offer them more flexibility, allowing them to adapt to rapid changes in supply and demand.

The availability of second-use batteries (such as from EVs after the end of their regular life cycle) has increased by 300 percent over the past three years. These are mostly lithium-ion batteries for short-term storage. Typically, these batteries retain 80 percent of their capacity.

For longer-term storage, different batteries are needed. Various developments in the technology will have to be made, including build-in units for photovoltaic (PV) systems and wind power.

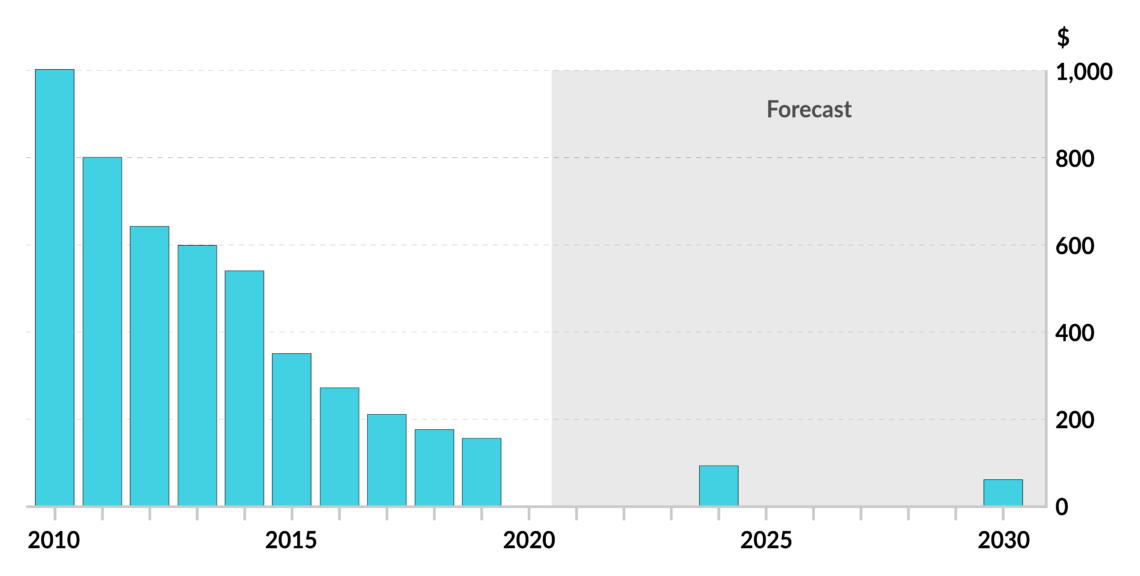

By 2040, large-scale production of batteries and intensive research could reduce prices by as much as 70 percent

The increasingly wide range of applications also enhances overall industry competition, thereby pushing battery prices lower. Between 2010 and 2018, battery production costs decreased by 45 percent. By 2040, in Europe, large-scale production of batteries and intensive research could reduce prices by as much as 70 percent from today’s levels.

Investment surge

During the last year and a half, EU businesses and governments have invested twice as much as China in battery technologies, making the bloc the world’s largest investor in the sector. Europe’s first gigafactory for lithium-ion battery cells is being built by Sweden’s Northvolt. The plant will have an initial capacity of 16 GWh and will expand up to at least 32 GWh. It will be located in Skelleftea in northern Sweden, which is a prominent region for raw material and mining, with a long history of process manufacturing and recycling.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) loaned Northvolt 350 million euros from its European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) to finance development. By 2030, the company aims to be able to produce about 150 GWh of battery capacity. Northvolt has also partnered with Scania, ABB and Siemens.

Europe, in fact, has become a major battleground for established battery producers such as Tesla, Panasonic, CATL and others. The phenomenon is being driven by electric vehicles – BMW signed a 2 billion-euro contract with Northvolt for the delivery of batteries for its electric cars, while Volkswagen is the main investor in a battery factory in northern Germany. Still, China is ahead in the production of both batteries and EVs. In 2019 it produced 230 GWh of battery capacity, and it remains the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, with 45 percent share of the global market.

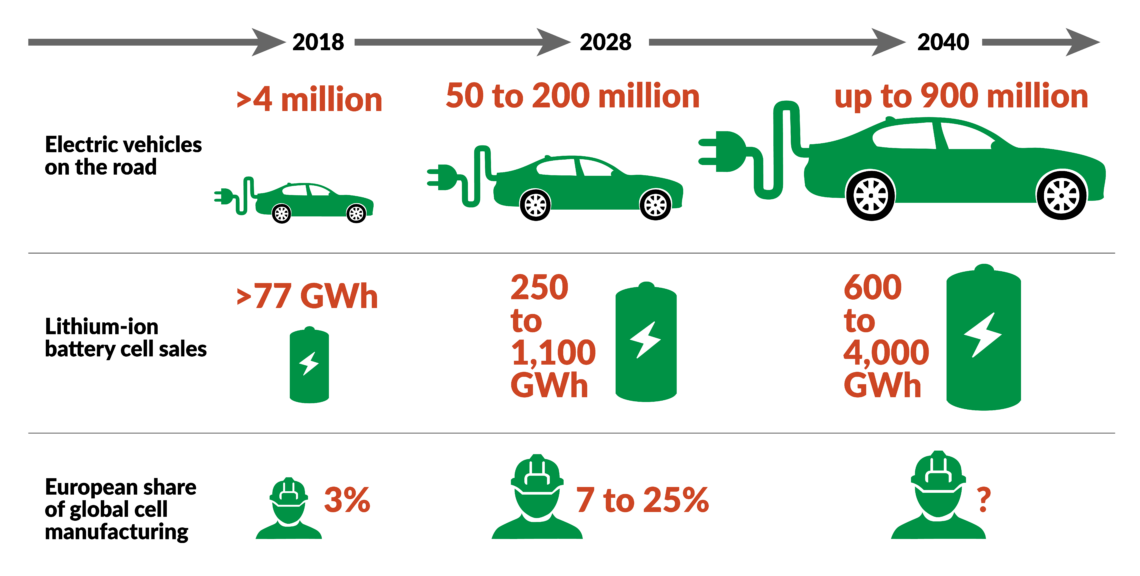

Batteries represent 35-40 percent of an electric vehicle’s production costs. As of 2019, only 3 percent of global battery cell manufacturing was taking place in Europe. (The European Commission wants to increase this to 15 percent by 2040.) Of the 70 announced gigafactories worldwide in 2019, 46 are based in China. Therefore, even if Europe increases electric-car production, China and other Asian countries are currently set to reap the benefits.

Facts & figures

As a result, Germany alone could lose 100,000 jobs in its automobile industry (which employs 830,000 people directly; indirectly it accounts for 2 million jobs). Another 100,000 jobs could be lost by its suppliers in other European countries. Across the EU, the automotive sector provides 13.3 million jobs, or 6.1 percent of the workforce. The EU, and Germany specifically, therefore have a strong incentive to build up their own battery supply chains.

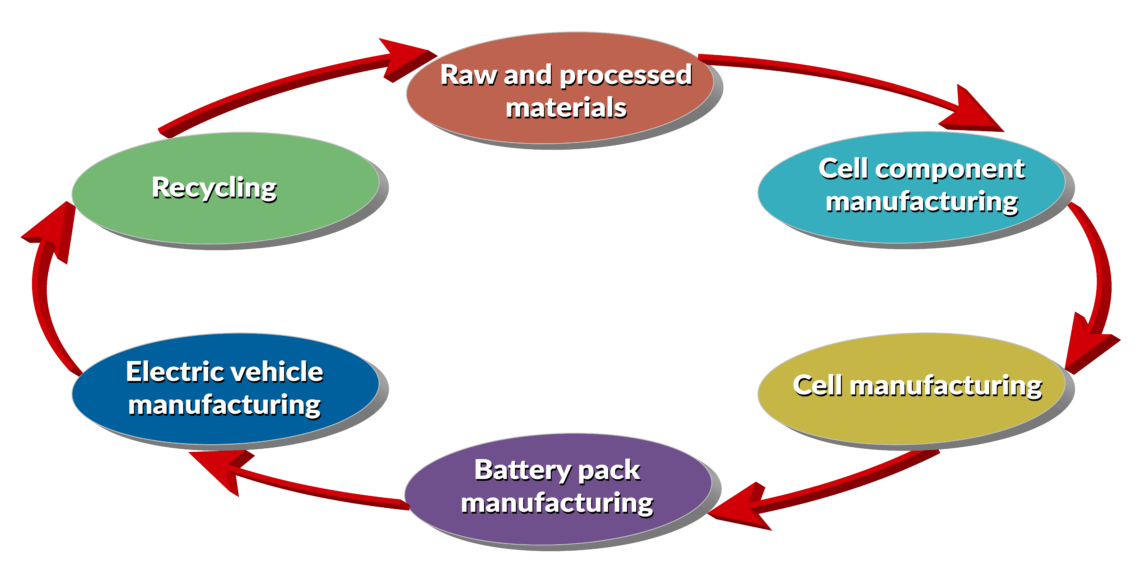

Importing batteries from Asia would also add considerably to the carbon footprint of EVs produced in Europe. But even if the batteries are produced in the EU, the raw materials needed to make them, such as cobalt, will have to be shipped from places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo to China for processing, and then to Europe. The hope, however, is that building up a strong EV market in Europe would provide a solid foundation for locating entire supply chains on the continent, thereby enabling large-scale battery production.

Global prospects

Another goal for the European Battery Alliance is to take the lead in designing and producing the most environmentally sustainable batteries, with the world’s highest recycling rates. In the long term, this strategy could help set international standards and create a blueprint for other countries to follow. In the short and medium term, however, the approach could slow down the development of a complete battery supply chain on the continent – especially due to cost factors and competition with China. The EU admits that it can never really match China’s state subsidies (both direct and indirect) nor its lofty ambitions.

China wants to dominate the global supply chain for electric cars – it is one important element in Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” national plan. The strategy outlines how to transform China into a high-tech superpower by supporting key industries and disruptive technologies, such as electric mobility, 5G, robotics, semiconductors and others.

Currently, 5 million of the world’s 1.1 billion passenger cars on the road are electric vehicles – that’s a 65 percent increase from 2017. However, the overall shrinking car market and reduced subsidies in China have slowed the rise.

Building gigafactories is not enough to create a complete battery value chain.

The number of EVs could rise to 200 million by 2028 and to 900 million by 2040, according to the European Commission. Consulting firm McKinsey & Company projects that battery demand from EVs produced in Europe will reach 1,200 GWh per year by 2040 – more than five times the capacity of the gigafactory projects operating or under development on the continent last year.

The expensive transition to electromobility has already cost jobs. With the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing recession, global car sales are forecast to decline from 88 million in 2019 to 69 million this year, and may not return to precrisis levels until 2022 or 2023. In Germany, the pandemic alone may cost 80,000 jobs in the sector.

Nevertheless, in Germany EV sales increased during the first six months of 2020, thanks to enormous subsidies. Still, however, more than 85 percent of all cars sold in Germany during the same period were the traditional, combustion-engine type. EVs suffer from drawbacks like the inability to travel large distances between charges and a lack of stations that allow for fast recharging.

Volkswagen plans to introduce nearly 70 new EV models over the next 10 years, investing 33 billion euros in the strategy. By 2029, it hopes to produce 26 million EVs. To realize this plan, the company will need more batteries than the total currently produced globally – equivalent to the amount that would be produced by 40 gigafactories the size of the one built by Tesla and Panasonic in Nevada. It has a capacity of 35 GWh, though Panasonic recently announced it would expand that figure by 10 percent with an additional production line.

Facts & figures

Because the carmaker’s battery suppliers can currently fulfill only 50 to 60 percent of its total demand by 2023, it is now investing 1 billion euros in homegrown battery technology and promoting new partnerships with external manufactures, including those in China such as CATL and Guoxuan. The company has a 900 million-euro joint venture with Northvolt for a battery manufacturing facility in Salzgitter, but that will not become operational before 2023.

Potential slowdown

Though the total costs for EVs are expected to fall by more than a fifth in the coming years, they are still likely to remain significantly more expensive than combustion engine cars until at least 2030. That factor could constrain the worldwide expansion of EVs. An even bigger problem is the shortage of a high-skilled industrial engineering workforce not just in Europe, but worldwide. Building gigafactories is not enough to create a complete battery value chain. For development and innovation in the sector to be sustainable, Europe’s new production facilities will need a readily available supply of CRMs such as lithium and cobalt. They will also require component suppliers and chemical engineers.

The number of electric vehicles could rise to 900 million by 2040.

In contrast to the EU, China has a robust strategy for securing access to CRMs. The EU itself, along with some member states, including Germany, have begun to address the CRM challenge only recently. China, with its centralized power structure, can compete more effectively than Europe on global raw material mining markets.

One of the biggest challenges for the EU will be expanding CRM mining in Europe so as to reduce dependence on imports from China and other countries, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which supplies the lion’s share of the world’s cobalt. It remains uncertain whether the planned mining projects in Europe can be implemented due to strict environmental regulations and a lack of public acceptance. EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton recently warned again that the EU’s increasing dependency on foreign countries (in particular China) for CRMs needs to be reduced. “The era of a conciliatory, if not naive, Europe has come of age,” he said.

Facts & figures

Positive signs

EV battery costs have already declined to less than $180 per kWh in 2019 from $650 per kWh in 2014. These costs need to drop further, to less than $100 per kWh, to make EVs cost-competitive with internal combustion cars.

While EV battery prices are falling, the distance over which they can power a vehicle is increasing. Moreover, research and development (R&D) has intensified in recent years. One important line of research is directed toward reducing the time it takes for EV batteries to charge. The competitiveness of the technology will also hinge on improving longevity – including using EV batteries in other appliances once the life of the vehicle is over. Progress has been made in developing entire lithium-ion battery “ecosystems” that include enhanced collection, testing, recycling and processing of batteries, but more needs to be done.

Europe has some of the best technical research facilities, institutes and universities in the world, putting it on a good footing to become a leader in battery manufacturing. The EU can use its R&D strength not only to help increase cost competitiveness, but to push for developments in battery technology that could offer added value, in terms of safety and environmental sustainability.

Facts & figures

Such capital-intensive activities will not fuel major job growth, due to the automated nature of battery production. Some additional jobs will be created, however, in maintaining infrastructure for battery technology, such as recharging stations.

Scenarios

Batteries have applications that go far beyond EVs, like solar photovoltaic power generation, wind power stations or in other parts of the power sector. Yet without a battery supply chain in Europe, the continent’s automotive industry will lose competitiveness and jobs.

Demand for EV batteries in Europe could also be influenced by the EU’s ambitious hydrogen plans, which also drive investment in green projects, including hydrogen fuel cells for trams and buses. Other technological developments, including distance charging, wireless power and energy harvesting, could boost demand for batteries. As the market grows, the risks and costs involved with developing power-dependent remote devices will fall. These developments still face limitations that are preventing widespread adoption – for now.

Together with the development of various hydrogen technologies, the growing European EV battery industry will alter both regional and global geopolitical dynamics. It will require new supply chains, trade routes and strategic partnerships – including for the secure supply of CRMs. These factors will result in new geopolitical alliances and rivalries that the EU will have to take into account as it formulates its common foreign and security policies.