Rising migration tensions on Mediterranean shores

Northern and southern European states are struggling to find common ground on mounting migratory pressures from Africa, risking political and economic consequences.

In a nutshell

- Migration from Africa continues to weigh on Southern European states

- Recent EU agreements have done little to change underlying dynamics

- Coming waves of climate migration will pose new challenges

Back in January 2009, the foreign ministers of Greece, Italy, Malta and Cyprus met in Rome to discuss irregular migration in the Mediterranean Sea. The result was a lengthy document calling for more coordinated European action on irregular migration flows and the smuggling networks behind them. The European Council had already adopted the European Pact on Immigration and Asylum in October 2008, but the practical effects were not significant.

Since then, the 2015 migrant crisis hit, during which well over a million migrants landed on European shores, causing an unprecedented political and social crisis. The Dublin Treaty, first signed in 1990 when such large flows were still unimaginable, was amended in 2003 (Dublin II) and 2013 (Dublin III). But its cardinal principle – that the place where a migrant first arrives is what governs reception issues and the related asylum claim – has proven to haunt the two countries most affected by the landings, Italy and Greece.

In addition, the ban on movement within the EU by asylum seekers has led to many migrants being turned back to their first-landing states by countries such as Germany, France and Austria. In 2019, for example, Italy saw more returns of asylum seekers to other European states than landings on its own shores. According to German authorities, in 2018 alone there were 35,375 known cases of migrants coming to Germany after arriving in other EU countries. Several planes leave German territory every month bringing such migrants back, mainly to Italy.

Little change

Then, on September 23, 2019, the interior ministers of Malta, Italy, France and Germany met in Valletta to sign the Malta Agreements, for the redistribution of migrants arriving by sea. Presented as a milestone, the deals faced a major criticism: compliance was voluntary. For example, Italy’s burden of first reception remained unchanged. Of the approximately 53,000 migrants that landed between October 2019 and May 2021, only about 990 were relocated to other European countries – fewer than 2 percent of the total. Nine out of 10 of the migrants rescued in the Mediterranean remain in Italy.

Statistics further show that economic migrants manage to find a job 80 percent of the time, while only 30 percent of refugees or those seeking family reunification succeed within the first five years of entry. Regular migration channels, too, have shrunk for various reasons, just as irregular ones have increased.

The sparks of the last several months will fuel the slow-burning controversy between various European nations over migration flows.

The 2008 document was revived in September 2020, now dubbed a “New Pact on Migration and Asylum.” It described a “comprehensive approach” meant to streamline integration processes and improve border control – declaring that the Dublin rules were now outdated and that a new framework was needed. “Rules for determining the Member State responsible for an asylum claim should be part of a common framework, and offer smarter and more flexible tools to help Member States facing the greatest challenges,” it read. All member states were now supposed to contribute, but little had changed: coastal countries continued to be left on their own, and the Dublin approach effectively survived.

Another important issue on the table is the fight against the smugglers behind the complex human trafficking networks. This effort cannot be waged by individual states, but only through coordinated work – not just in Europe, but also in Africa, as discussed in the July 2020 ministerial conference between the EU and its African partners.

Crisis point

On November 12, 2022, Cyprus, Malta, Greece, and Italy met again and issued a joint communique calling for more action from the rest of Europe to manage migration flows. They argue that other EU member states continue to leave much of the problem to these four nations, whose place along the Mediterranean makes them the easiest destination for those leaving Africa.

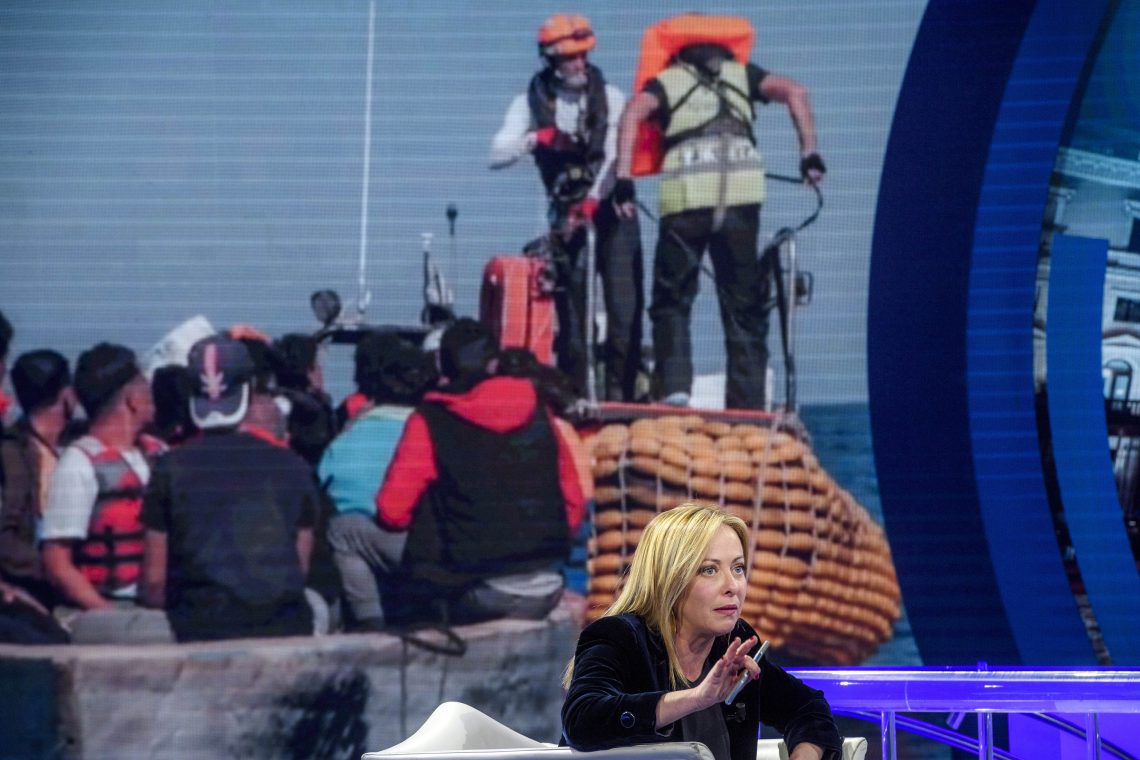

This latest statement came after the Ocean Viking affair. The ship, leased by the NGO SOS Mediterranee, was blocked by Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s government from docking to land the 234 migrants aboard. As a result, after a diplomatic tug-of-war between France and Italy, the vessel was forced to the distant port of Toulon, where only 111 people were accepted to be sent among various European countries, with the other 123 deemed unfit for protection. Many of them, however, fled from the reception center.

After this incident and the joint November 12 statement, an extraordinary council of EU interior ministers gathered on November 25, where they agreed on “the need to step up EU support and cooperation with all partner countries and organizations to prevent departures and avoid loss of life, to address the root causes of migration and fight against smuggling networks and to significantly improve return and readmission.”

Italy’s new interior minister, Matteo Piantedosi, was very positive about the meeting’s draft action plan, stressing that there is no friction with France. Yet on the same occasion, French Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin clarified that Paris will not accept asylum seekers who have landed in Italy until Rome respects “maritime law” and refuses to disembark ships loaded with migrants rescued in the Mediterranean.

Facts & figures

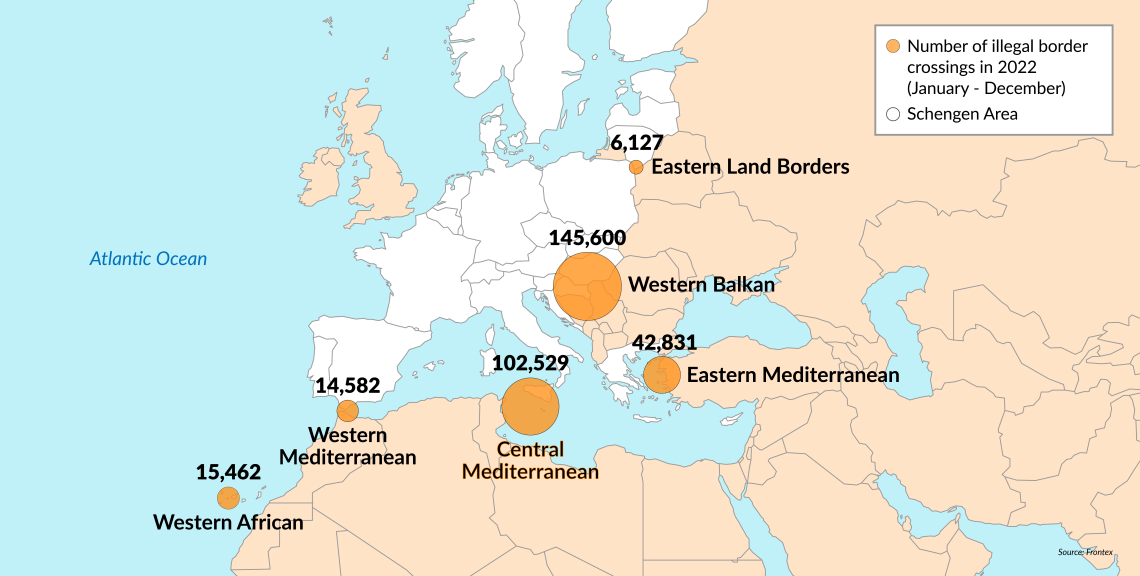

Illegal border crossings into the EU, 2022

The November action plan consists of 20 points across three pillars: working with partner countries and international organizations; more coordination on search and rescue; reinforcing the so-called Voluntary Solidarity Mechanism and the Joint Roadmap. In addition, on November 28, the EU’s Foreign Affairs Council met in Brussels as a follow-up to the European Union-African Union summit on February 17-18, 2022.

However, from the viewpoint of southern Europe, the situation still appears the same. Ms. Meloni, Italy’s recently elected prime minister, emphasized in a December 2022 conference that repatriation management must be “Europeanized” – that no country can shirk its duties, and that cooperation with African partners on human trafficking is necessary. Previously, German Ambassador to Italy Viktor Elbling stated that Rome “is doing a lot in terms of migration but it is not alone.” He noted the numbers for the first nine months of 2022: 154,385 asylum seekers in Germany; 110,055 in France; and 48,935 in Italy (or 0.186 percent, 0.163 percent and 0.083 percent of the population respectively).

Scenarios

The primary problem facing Europe in the next few years is controlling the inflow of migrants from Africa. As yet, no common EU strategy has been implemented to stem the Africa issue at its root. If European politicians dislike the political and economic effects of (largely economic) immigrants and refugees, the consequences will be far worse when ten times their number in climate refugees arrive. A failure to confront this challenge now, while the numbers are relatively small, will unleash the political and economic chaos of climate migration.

In one scenario, northern European nations begin to cooperate in earnest with their southern peers. This appears unlikely at the moment, with decades-old frictions still present. Fixing the Dublin framework will be a top priority. Constructive cooperation between France and Italy would help, but does not currently seem possible.

In a second scenario, northern and southern European member states stick to their respective positions. The two have substantial differences in managing migrants, whose increasing number only exacerbates the tensions already present. Although their diplomats collaborate regularly, national politicians appear less oriented toward the same goals. The sparks of the last several months will fuel the slow-burning controversy between various European nations over migration flows. The decisive element for progress still seems missing: common will toward a shared project.