Macron’s European defense initiative can work

France’s nuclear capabilities have rarely played a relevant role in French or European defense. Now, President Macron sees them as the basis for a new European security initiative. If construed properly, it could serve both EU and NATO geopolitical interests.

In a nutshell

- President Macron wants France to lead a revitalized Europe

- France’s status as a nuclear power puts it in a unique position

- A European carrier battle group could serve all stakeholders

French President Emmanuel Macron’s initiative to reinvigorate the European Union is in line with the Gaullist tradition. It aims to constrain Germany by strengthening Franco-German ties and to consolidate continental Europe, with France as its main global representative. It also aims to engage the United Kingdom in a bilateral framework based on both countries’ status as nuclear powers, with France backed by continental clout.

By achieving these goals, France would become the principal European partner of the United States. At the same time, it would seek a more constructive role in dealings with Russia, and would display some independence from the U.S.

Since entering office, President Macron has tried to rejuvenate Europe’s politics and global competitiveness. His initiative focused above all on economic and financial matters, where France needed to cooperate with Germany and learn from its social model. With Berlin’s help, Paris hoped to compensate for its own economic weakness. However, its plan also required Germany to make compromises on many key issues, the eurozone first and foremost.

The tandem with Germany did not develop as envisaged and did not generate the expected economic growth.

The tandem with Germany did not develop as envisaged, and without full German support President Macron’s effort to revitalize the EU did not generate the expected economic growth, either. Russian President Vladimir Putin was not exactly responsive to French overtures. U.S. President Donald Trump’s support for Brexit and Europe’s souring relations with Washington left President Macron with few options.

New opportunity

In Brexit, President Macron saw the opportunity to consolidate the EU without the UK and to capitalize on France’s military role. Becoming sole nuclear power in the EU revived French ambitions to demonstrate both independence and European leadership.

President Macron had a few factors on his side. France had exclusive control over its nuclear weapons, though it had invited European nations to engage in a dialogue about their use. Its nuclear-power status reinforced its sovereignty, while at the same time supplemented U.S. defense of Europe. Its nuclear weapons could deter Russia – but any actions Moscow took against Europe would likely be well below the threshold that would warrant a reaction.

France also aspired to become the lead nation in building more cooperative relations with Russia. At the same time, it would reassure the rest of Europe that it could protect it in case of Russian invasion – a nearly nonexistent threat.

Facts & figures

France’s nuclear force

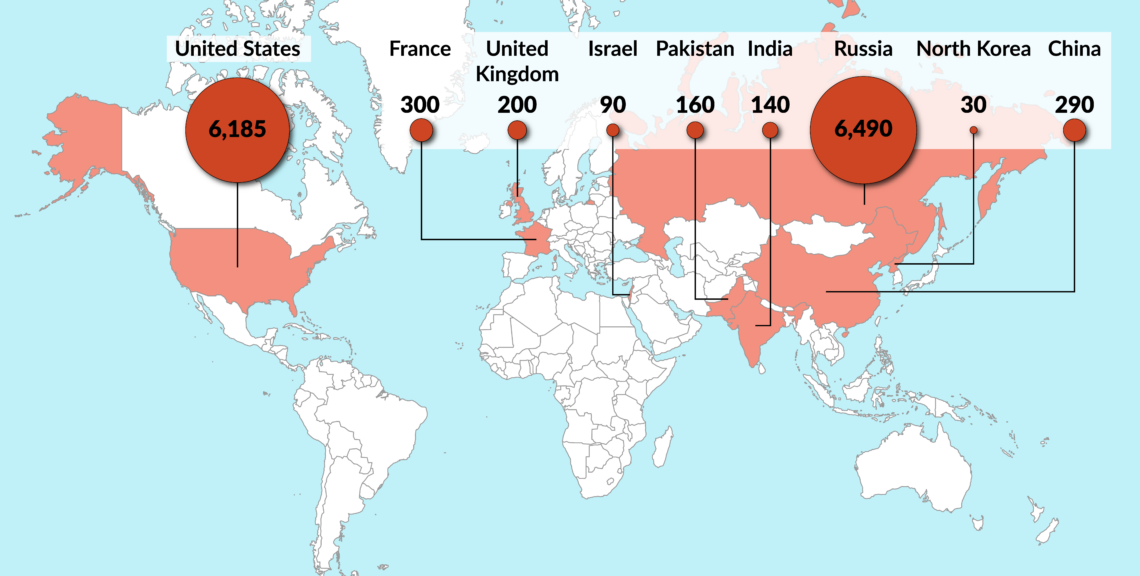

France has the third-largest nuclear weapons force in the world, at about 300 warheads. Most of these are designed for delivery by cruise missile, launched either from a submarine or from strategic bombers. These figures were confirmed by then-President Francois Hollande in 2015. According to estimates, approximately 290 of the warheads are currently deployed, with the other 10 in reserve.

In 2016, France’s nuclear deterrence budget was 3.6 billion euros, according to the French Ministry of Defense. In 2018, the government committed 25 billion euros to the country’s nuclear forces for the years 2019-2023.

Source: Arms Control Association

The French nuclear card

France’s nuclear dream dates back to its humiliation in the Suez crisis of 1956. Since then its ambitions have had little effect on Europe’s political evolution. And yet President Macron’s initiative does deserve the dialogue that he hoped to begin, even though his assumptions about the future of nuclear deterrence and its relevance for European security may be wrongheaded.

Facts & figures

In fact, profound changes on the continent and intensifying global competition mean both nuclear deterrence and the future of Europe’s defense need an agonizing reappraisal. Yet the strategic culture President Macron hopes to bring about is, regrettably, on no other government’s agenda.

Before Brexit, the nuclear forces of France and the UK had no role within the EU, nor did they have strategic relevance in NATO. Now, France wants to use its nuclear weapons as deterrents within a future European security system. Finding a role for these weapons is the only way to derive some political value from them. But without a unifying threat and with American protection still well in place, it would seem there is little need for further deterrence measures.

Its recent political shifts notwithstanding, France continues to seek a European and global role commensurate with its national identity, despite the disparity between its means and ambition. Since the mid-1950s, French European initiatives have repeatedly been frustrated.

Former U.S. Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger described this ambition as: “A Europe … unified on the basis of states, of which (France) would play the dominant role.” France retained this desire despite defeats in European wars, the end of colonialism (especially the bloody Algerian war), the reemergence of European rivals and repeatedly being rescued by the U.S. It held on to this ambition even after it abdicated its role as a global player following the Suez crisis. The late Egyptian President Anwar Sadat once said the episode had put France and the UK “in their right place as powers neither big nor strong.”

De Gaulle’s legacy revisited

Without Charles de Gaulle and the Fifth Republic, this presumably would have been the end of the story. De Gaulle’s vision was to compensate for France’s losses by forging a Europe that could deal with a divided Germany, a Russia with global ambitions and the U.S. as a preeminent power. The concept would both provide protection and allow France to leverage its position to gain power.

It was de Gaulle who gave France’s nuclear arsenal a political dimension. He hoped that one day it could put his country on equal footing with the U.S. and on a superior level to Germany, while protecting it from Soviet Russia (though able to open its own avenues to approach Moscow). Predictably, this vision never materialized.

After the Cold War, the rationale for added protection vanished, though France’s special status remained.

That left France as a part of the American nuclear umbrella. But it was also tempted to try to drag continental Europe – especially Germany – under French protection. When the Cold War ended, the rationale for added protection vanished, though France’s special status as a nuclear power remained. This unique position was initially camouflaged by formulae like “France has the bomb and Germany the Bundesbank,” but then Germany gave up its central banking preeminence to the European Central Bank in return for French acquiescence to German unification. European integration slowed, complicated further by hasty enlargement and inclusion policies.

Since de Gaulle, France has repeatedly invited Germany to share the costs of the French nuclear force in exchange for unspecified commitments. In 1998, as part of the European defense initiative in Saint-Malo, France and the UK agreed on joint measures to enhance nuclear cooperation – with occasional bilateral steps to follow. However, very little happened except that the two countries arranged for British aircraft to operate from French carriers and vice versa. The financial crash in 2008, the crisis over Ukraine and the broader geopolitical shifts caused by a more assertive China and a less multilateralist U.S. changed European nations’ agendas.

Running out of options

President Macron’s European initiative has therefore slowed down again. Efforts to shift focus to the Mediterranean and North African agenda did not bear fruit. Nor did his attempt to bypass the ostracism of his government over its Russia policy through bilateral diplomacy. Moscow is focused on the U.S. and China, and with President Macron’s European revivalism floundering, there was no incentive for Russia to engage with Europe.

Yet President Macron is determined for his initiative to succeed somehow, all the more so as his domestic reforms were met with violent opposition in the streets. But without EU partners on board, he has begun to run out of options. He chose the Munich Security Conference to play the French nuclear card once again. In the absence of a major threat to the bloc, he proposed developing a European dimension for the French force. Since there is no scenario that would call for using nuclear deterrence in Europe, he proposed that Europe build up a defense system as a supplement to NATO.

European nations were invited to become part of a joint strategic dialogue, backed by French nuclear power. However, NATO already has a Nuclear Planning Group (France has opted out), so there is little interest among members to join yet another such talking shop. Moreover, there are suspicions that France may be trying to support its own defense companies in initiatives such as replacing Germany’s Tornado aircraft for carrying NATO’s U.S.-made B61 nuclear bombs.

Above all, the situation makes it clear that nuclear weapons have lost their political value in Europe – or so it seems under the current circumstances. While nuclear capabilities have long been used as political weapons, for France they are only an ultimate insurance for virtually unthinkable European scenarios.

The only strategic context for reconsidering this conclusion would be in view of distant geopolitical changes that affect Europe at large. This would pertain less to continental crises, and more to risks that might arise from Europe’s dependence on other global centers of decision-making (Washington and Beijing, for example).

Deterrence without a threat

The absence of a major threat laid bare the missing strategic rationale for this European defense project. Yet as European political rhetoric has repeated time and again – not least in the Lisbon Treaty – Europe will not prevail on the global level if it cannot protect its geopolitical sovereignty and economic viability. U.S. protection is uncertain and Europe’s economy relies on its import and export markets. However, Europe’s defense capacity does not address the challenges ahead.

Europe’s defense capabilities are currently built as if an invasion from Russia – with intent to occupy and control parts of the continent as it did during the Cold War – is still the danger for which it must prepare. To assume that today’s far weaker Russia would ever consider occupying Europe is outlandish. Yet the Cold War showed that military power can be decisive in political competition.

Ursula von der Leyen has rightly emphasized that the EU will not become a defense union.

Europe requires a stable configuration of states that all believe they are best served by cooperating within a single construct. This applies to the EU and its single market, as well as to whatever the most suitable security framework may be. NATO has long ceased to be a primary political framework. New European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has rightly emphasized that the EU will not become a defense union as the French have long dreamed. That was true when the UK was a member of the EU, and it remains true with the UK outside the bloc, contrary to what integrationists suggest.

A future multilateral framework European defense would need to be built around a core that includes France, the UK and Germany. A proposal for a European Security Council is on the table. Such a system could evolve in informal and pragmatic ways. Since Germany has long abstained from prioritizing military leverage, the leading role would naturally fall to France. The Atlantic alliance – which even when it played its most crucial role, was never considered permanent – should be treasured as a construct to keep U.S. decision-making within a common structure, even if Washington’s priorities will increasingly be defined by American exceptionalism.

However, there is no institutional architecture for France’s nuclear force. And the EU has no structure for the unlikely event in which France would be required to provide a deterrent for the bloc. Still, the British and French nuclear forces are somehow seen as insurance for unspecified circumstances. Indeed, globally, nuclear risks are beginning to spread again, and containing them will prove a challenge.

For Europe, nuclear deterrence and arms control have little direct importance. However, the continent is unavoidably part of an intensifying quadrilateral global competition with the U.S., China and Russia. Europe is uniquely vulnerable due to its nearly total dependence on external supplies and global trade. In an escalating conflict, maritime capabilities could be crucial.

A European carrier battle group

French and British carriers and submarines could also come into play, if only to demonstrate European strategic clout. Coordinating French and British submarines with nuclear weapons, for example to improve rotational flexibility, has been on the bilateral agenda long before. A European battle group could be built around British and French carriers.

Carrier battle groups are complex systems requiring antiaircraft, anti-ship and anti-submarine capabilities, as well as reconnaissance and communication systems, among other things. Nonnuclear partners can provide many of these capabilities, without impairing individual countries’ control of their own nuclear forces. Such a system would allow joint planning and crisis management. It is a conceivable project, though it would require a new format for cooperation.

A European carrier battle group would be multinational and would serve European strategic interests.

Unlike land-based nuclear-capable aircraft (which can easily be targeted before takeoff), and unlike submarines (which will be completely under national control), a European carrier battle group would be multinational and would serve European strategic interests. Russia, by contrast, has one carrier without the protection of a carrier battle group.

So President Macron’s initiative does not lack strategic perspective altogether. A project like a European carrier battle group would keep the UK within the European framework, allow bilateralism between the two European nuclear powers, represent a force even the U.S. could consider a supplement and provide Europe with a reassuring and politically meaningful capability. It could boost the French initiative in ways that increase Europe’s geopolitical weight in the world.

Initiatives to make the French and British nuclear forces political instruments should not aim prematurely at institutional arrangements, but at joint projects that could serve common interests. This differs from a European army that would require inter-state arrangements. But while effective coordination of naval forces is more complex than that of land or air forces, it would better provide Europe with strategic independence. It allows France a core capability, it invites enhanced cooperation between France and the UK, and offers a political opportunity for European cooperation. President Macron’s invitation to discuss Europe’s future strategic culture would at long last find a political agenda.

Yet without a joint project at its core, the initiative will not move beyond esoteric intellectual exercises. Previous initiatives like the European Space Agency, CERN and the Letter of Intent Group (on the European defense Industry) could provide lessons on how to structure such cooperation outside NATO and the EU – but potentially in support of them. This indispensable first step would need to be taken by France and the UK, though with the backing of other key nations like Germany.

None of this can happen before the EU and the UK agree on their future relationship. But the 1998 Saint-Malo Declaration and the 2010 Defense and Security Cooperation Treaty show that Paris and London can work together on such issues. These documents could form a basis for bilateral cooperation outside NATO and the EU, but with a European perspective. And President Macron undoubtedly favors a European approach.