2019 Global Outlook: Economic reform in France

Like his predecessors, President of France Emmanuel Macron has ended up raising taxes instead of reforming the economy. The “national dialogue” to come following the Yellow Vest protests could bring better democratic representation – and more economically responsible governance.

In a nutshell

- Presidents Sarkozy and Hollande mostly raised taxes to cover rising deficits

- Emmanuel Macron is following a similar path, despite promising to be different

- Centralized bureaucracy and entrenched interests tend to halt real reform

In France, 2018 did not bring the promised economic recovery, while the Yellow Vest movement in November and December shook the government. Instead of increasing taxes to reduce deficits, the authorities backpedaled, pledging to implement measures that will increase both public spending and deficits in the short term. Some of these measures are supposed to be decided upon in a “national debate.” The question is whether this debate will help reverse France’s chronic overspending by redefining the country’s priorities and shrinking a bloated state administration.

To better understand the prospects for reform, a look at recent French history will be helpful.

Sarkozy’s drama

Back in 2007, many hoped President Nicolas Sarkozy could be the reformer that France desperately needed after years of inaction. Those hopes were dashed. President Sarkozy’s reforming phase in the first 18 months of his term was unsuccessful. The “hyperactive president” chose a strategy based on “choking and conciliation.” He hoped to “choke” his opponents in the bargaining process (especially the trade unions) by opening many fronts of reforms, but they were ready for that tactic. The “conciliation” part – offering compensation to ensure the passage of reforms – ended up costing much more than the previous status quo.

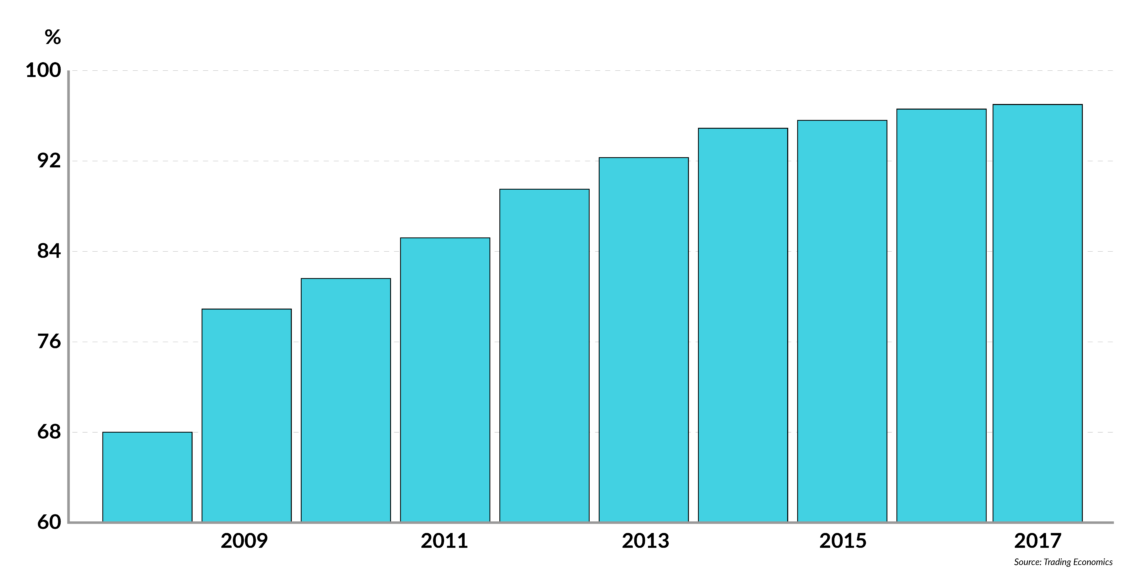

Under President Sarkozy, public debt increased by nearly 50 percent, or more than 600 billion euros.

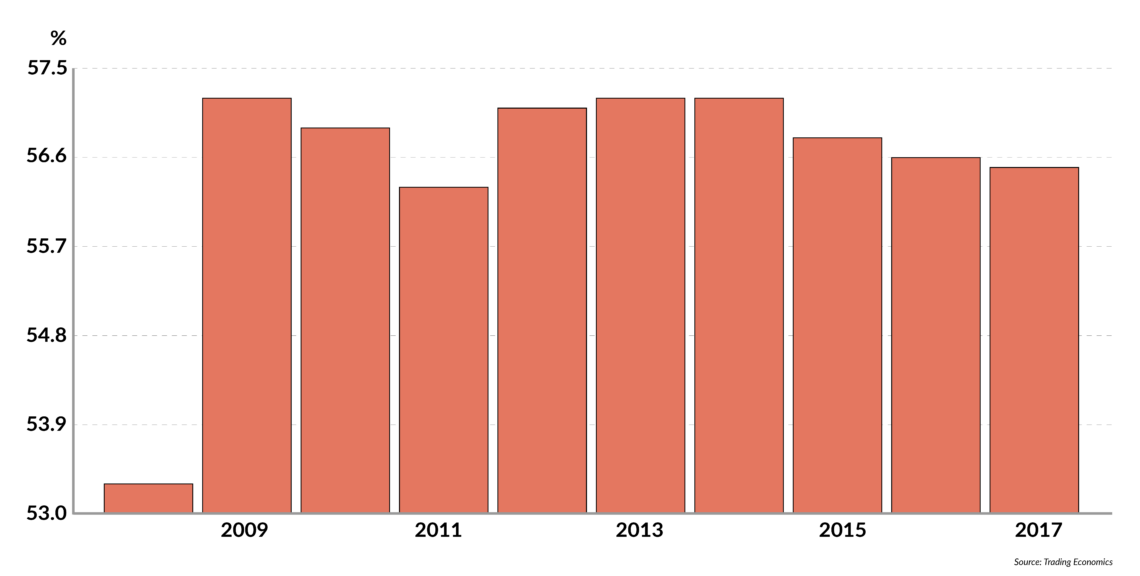

In the second phase of his presidency, in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, Mr. Sarkozy advocated a “return of the state.” This in a country where government spending already equaled 53 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). That figure shot up to 57 percent, while public debt increased by nearly 50 percent, or more than 600 billion euros. So much for public finance reform.

In January 2012, Standard & Poor’s downgraded France’s triple-A credit rating. The government responded by pledging to reduce the deficit, but it essentially relied on raising taxes rather than reducing spending to do so.

Hollande’s turn

In 2012, Francois Hollande was elected. His platform was far from pro-market, instead consisting of interventionist recipes to curb unemployment. In the first phase of his mandate, the government increased taxation on capital and on the rich. The French Public Investment Bank was founded that year, and again showed how inefficiently bureaucrats without any “skin in the game” can manage investment. The predictable outcome soon materialized: sluggish growth and higher unemployment.

In the second phase of President Hollande’s term, during which current President Emmanuel Macron was economy minister, the administration focused on pro-business reforms, especially in terms of taxation, labor market flexibility and increasing competition in certain sectors (like intercity bus lines). Given the scale of change needed, these were far too timid. Moreover, reforms meant to “simplify” life for business eventually brought more administrative complexity and less transparency.

Facts & figures

France government spending to GDP (%)

Facts & figures

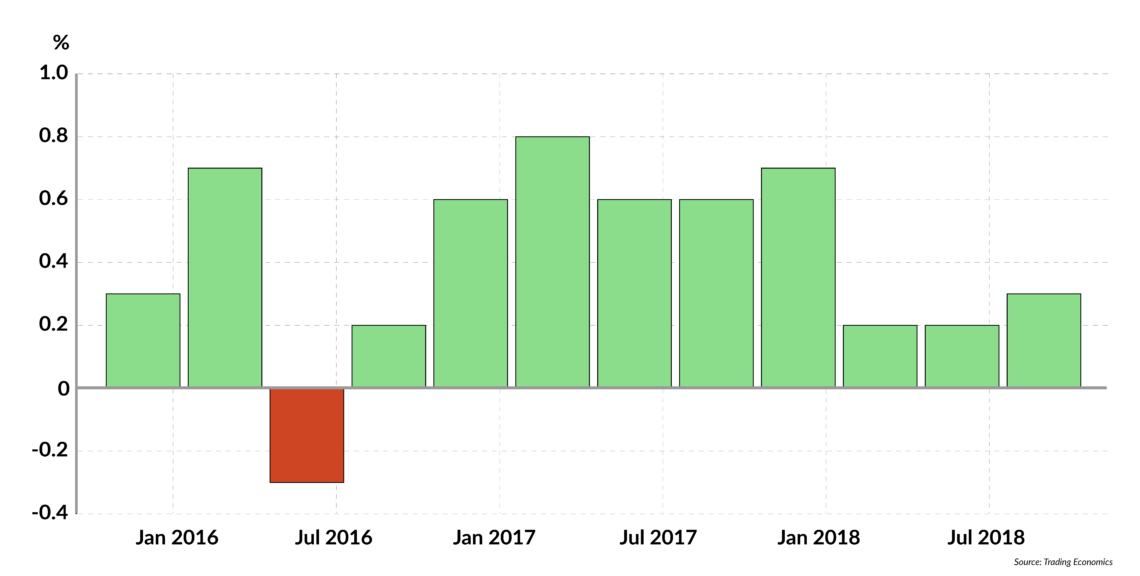

France GDP growth rate

(%, quarterly)

Facts & figures

France government debt to GDP (%)

One good reform that came during President Hollande’s term was a ban on members of parliament holding more than one elected office (the practice created a conflict of interest between local and national levels). Its positive effects on accountability, however, were short-lived. The potentially fruitful territorial reform – reducing the number of administrative regions to increase efficiency – did not bring much economic benefit.

The 30 percent pay cut for the president and his ministers was welcome, but it was not applied to most highly paid people in the government. The number of civil servants (more than 20 percent of the country’s workforce) continued to rise. Public spending and debt grew, although at a slower pace than under Mr. Sarkozy. Still, President Hollande’s promises for “fiscal seriousness” again involved increased taxes rather than a reduction in public spending.

Reform revolution?

The lesson is that “reform” in France usually ends in more taxes, not less public spending. The French political-administrative complex’s many vested interests almost always win. Observers were curious to see how President Macron would fare, given his attempts at reform during Mr. Hollande’s term. As I pointed out in a report in February, his “revolution” started disappointingly. I was skeptical about the prospects for any deep reforms or meaningful activity. That skepticism was well-founded: as with Mr. Sarkozy, Mr. Macron’s many “reforms” leave much to be desired.

The lesson is that ‘reform’ in France usually ends with more taxes, not less public spending.

His labor market proposals focused on allowing contracts to be negotiated at a subnational level. Yet, the reform ended up strengthening the tendency to conduct such talks at the sectoral level – with strong unions – and did not always allow for bringing the negotiations down to business units, which could have yielded more efficiency.

Reforms of unemployment benefits, social housing and additional pension schemes have centralized or even nationalized these systems, unveiling a decidedly statist bias in Mr. Macron’s declared liberalism. To reduce deficits, President Macron went back to his predecessors’ old recipe of more taxes instead of shrinking public spending. And when taxes were cut in one area (housing), they increased elsewhere (fuel). France now leads the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in its tax burden on the economy, at 46.2 percent of GDP.

Macron’s challenge

Little wonder Mr. Macron’s reforms have had a negative effect on growth. After a period of exaggerated euphoria in 2017, when France’s economy grew by 2 percent, 2018 fell flat: the economy expanded by only 0.2 percent in the first and second quarters (well behind the European Union average), and a timid 0.3 percent in the third quarter. The Yellow Vest movement’s blockades of roads, commercial areas and storehouses in November and December killed any hope for the fourth quarter. France’s unemployment rate fell only slightly – by 0.5 percent – in the 12 months to November 2018 (the third quarter even noted an increase). It is still higher than the EU average.

Mr. Macron’s challenge is to reduce the tax burden and public spending (57 percent of GDP) at the same time. The clock is ticking: France spends more than 10 percent of its government budget (42 billion euros – its second-largest expense) on debt servicing alone. Since borrowing rates could rise, fiscal reform has become even more urgent.

Cutting spending is a daunting task because France’s dysfunctional democracy puts numerous constraints on governments that want to downsize the bureaucracy: these include a hermetic, self-protecting administration and, beneath it, a layer-cake, semi-decentralized accountability-killing state apparatus, as well as a corporatist social model that keeps generating centralized entitlements. The Yellow Vest protests could offer an opportunity to rethink France’s democracy through the promised “national debate.” It is time to build a consensus on national spending priorities.

Scenarios

One scenario sees the Yellow Vests’ early demands – lower taxes, more efficient public spending and better democratic representation – bringing more transparency and accountability to government. For example, putting civil servants on standard employment contracts (they now enjoy jobs for life) would be key to shrinking the bloated state administration.

If France moves toward more decentralized democracy with local fiscal autonomy (as in Switzerland), it could give citizens more power to keep local taxes and public spending in check. Eventually, citizens would gain more influence over spending priorities, while expenditures would be streamlined and the myriad of costly agencies reduced. Public spending and taxes would fall, spurring growth.

The second scenario is more pessimistic. A precondition for the first scenario is that citizens finally get the message reformers have been sending for years: you cannot have more public spending and lower taxes at the same time. The latest, far more populist, demands of the Yellow Vests go against this basic tenet of fiscal responsibility. Moreover, it will not be so easy to dismantle the “one and indivisible” French Republic; the French administration’s ability to frustrate any attempt at downsizing is legendary. Thus, the “national debate” would only be a waste of time or make things worse.

However, it is hard to see how France, given rising interest rates and European commitments, could continue kicking the can down the road. New, hidden taxes and fees could be devised to pay the bills, but that would hamper growth.

This scenario is even darker considering how unprepared the administration is for the inevitable consequences of the withholding tax reform, which entered into force on January 1, 2019. In France, income tax is calculated based on household units, not individuals, which adds greater complexity to the system. Such complications mean there could be a huge number of disputes involving not just households and the tax administration, but also companies, the new de facto tax collectors. It is a perfect illustration of how “simplification reforms” end up creating more complexity in France. No matter which way the government turns, the bureaucracy wins again.