The future of food

The future of food production is central to dealing with challenges of a growing world population. Introducing more crop biodiversity requires rethinking outdated governmental policies. Future success hinges on international cooperation, especially with China and India.

In a nutshell

- Crop biodiversity requires new policy models

- The pandemic will present continued risks to food security

- Future success hinges on international cooperation

What are the main challenges facing the world’s growing population? Four will likely be top of mind: health, poverty, climate change and food. All are interconnected, but food is central to each of the others.

The data paints a worrying picture. Pre-pandemic projections from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) show that over 3 billion people, or around 40 percent of the world’s population, cannot afford a healthy diet. The latest report published by the Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC) reveals that economic hardship caused by pandemic-related restrictions, conflict and the persistent threat of adverse weather conditions are driving food crises. In 2020, the number of people facing acute food insecurity hit a five-year high.

More than 820 million people suffer from hunger, while about 2 billion people lack one or more essential micronutrients and about 2 billion are obese or overweight (the two latter categories can often overlap). An unhealthy diet is a major contributor to premature death and disease; specialists estimate that five times more people died from causes related to malnutrition than from Covid-19 last year.

World Bank data shows that the total global population reached 7.75 billion in 2020. The UN projects that it will grow to 8.5 billion by 2030 (a 10 percent increase), and further to 9.7 billion in 2050 (26 percent) and 10.9 billion in 2100 (42 percent).

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030, over the coming decade, demand for agricultural commodities – including for use as food, feed, fuel and industrial inputs – will grow at 1.2 percent per year. Even though agricultural production is expected to increase by 1.4 percent per year, which in theory could meet that rising demand, it will likely not be enough to solve problems of food security and malnutrition.

Climate debate

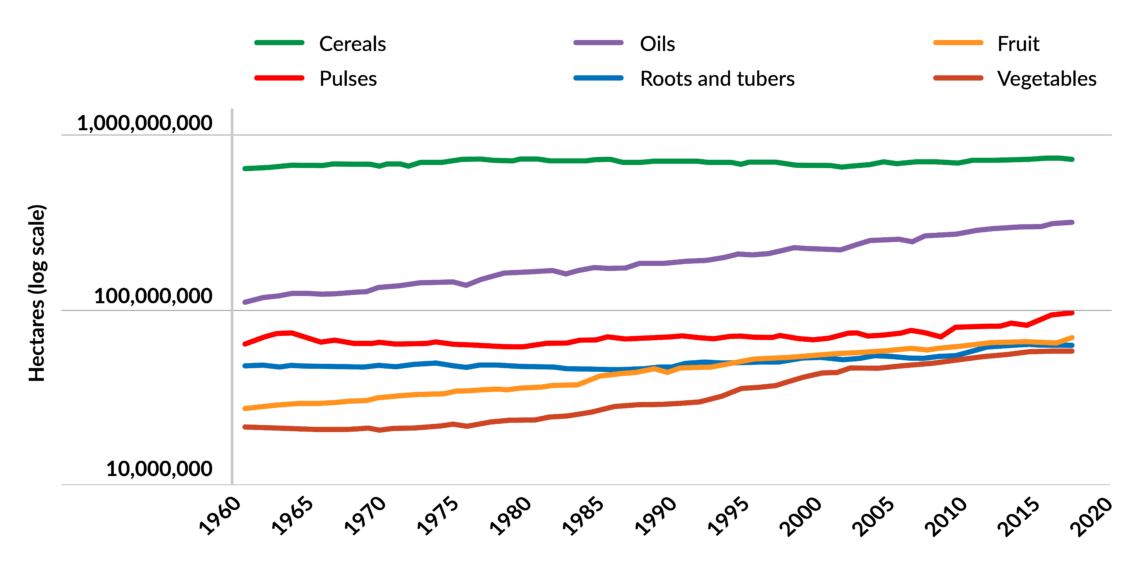

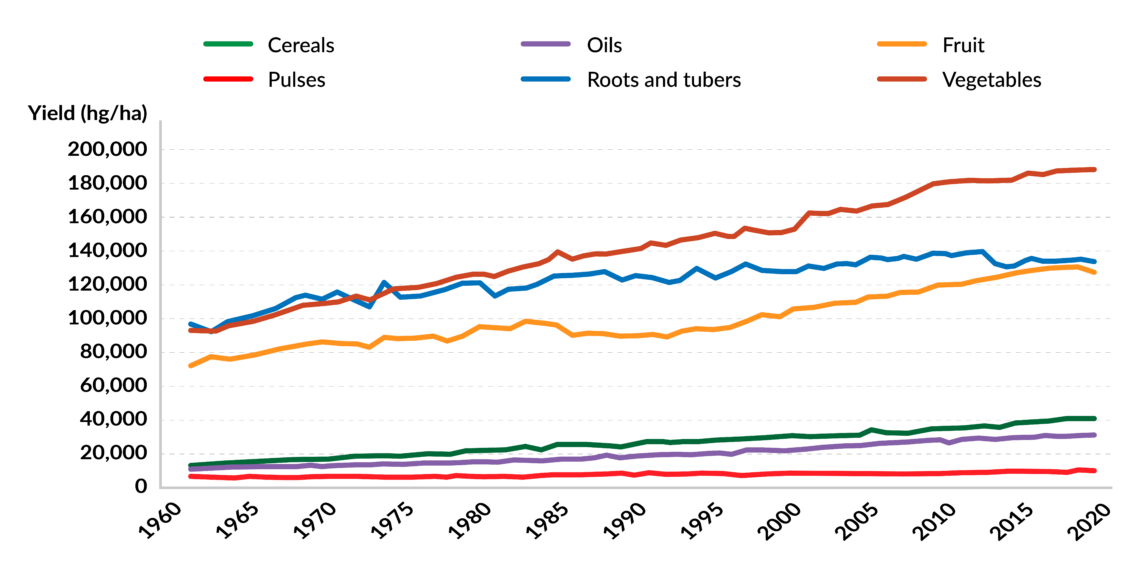

The factors that most influence food production are land and water availability, climate, productivity and technology. The intensification of agriculture since the 1970s with the use of advanced technology has improved productivity without a significant increase in cultivated areas. At the same time, it helped concentrate production in a limited variety of plants and animal species, which in turn triggered diseases, pests, uncontrolled weeds and soil degradation. Many came to consider agriculture, responsible for almost a third of greenhouse gas emissions, a “climate villain.”

Demographic trends, urbanization and economic constraints are likely to impede major diet changes in the medium term.

Policy discussions around the world are now focused on how to produce more food, while at the same time reducing negative effects on the environment. Among the solutions discussed today, most are focused on precision agriculture and sustainable agricultural methods, which allow further reduction in the use of natural resources and a decrease in pollution and waste.

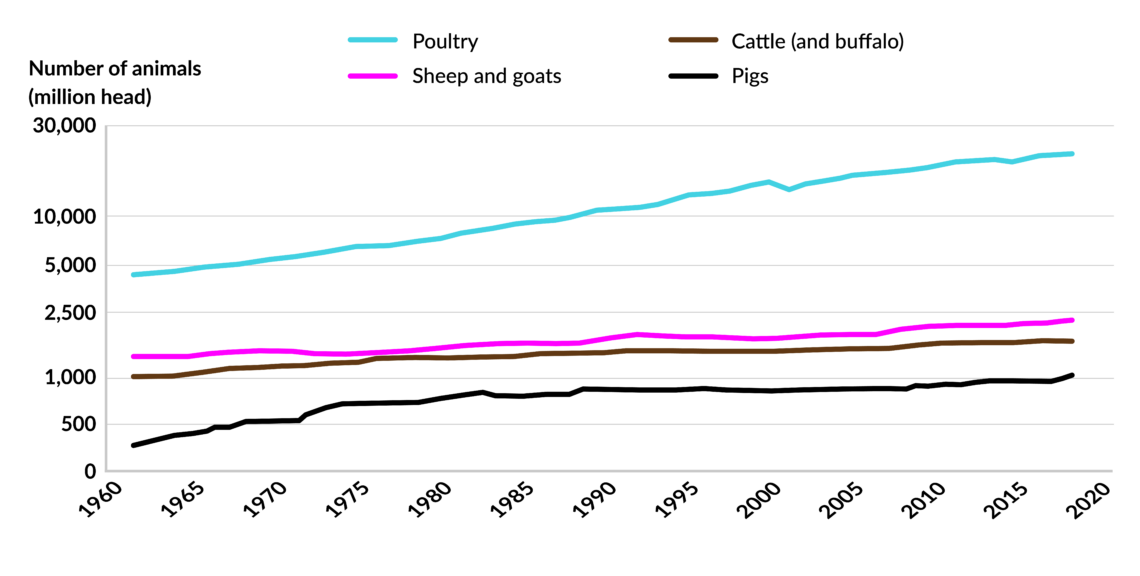

But other ideas are more radical – like changing the world’s diet by reducing the consumption of animal products (with many claiming that livestock is the sector with the biggest impact on the environment, a debatable contention). Sometimes these radical ideas seem appealing. But it would be even more appealing, for example, to completely prohibit the use of plastic; and yet while people need plastic much less than food, few would support such a ban.

Specialists, during a recent webinar on “rethinking protein” in the global food system, called for rationality and more optimism. Indeed, we should be both rational and reasonable when considering solutions. Agriculture may not be the major component of most countries’ economies, but it provides the main source for our well-being. Furthermore, according to the FAO, more than 60 percent of the world’s population depends on agriculture for survival.

Facts & figures

Because the world needs not only more food but also more nutrients, it is not reasonable to advocate for reducing livestock production, since animal products are sources of many minerals and vitamins that we cannot get from plants. Instead, scientists suggest that we increase agrobiodiversity by broadening the variety of plants, animals and microorganisms used for food and agriculture. The data shows that agrobiodiversity could provide valuable solutions both for environmental and health issues, and increase food production to combat poverty and malnutrition. This offers grounds for optimism.

Policy changes

According to a 2019 report, of the 6,000 plant species cultivated for food, fewer than 200 make major contributions to food production. Just nine of these plants account for 66 percent of total crop production, and just maize, wheat and rice alone give us about 60 percent of our plant-based calories and 56 percent of our plant-based proteins. These three crops are far less nutritious than, for example, barley, millets or sorghum, and use much more water to grow. When it comes to livestock and fish production, the picture is also worrisome. Of the 7,745 local breeds of livestock still in existence, 26 percent are at risk of extinction. Nearly a third of fish stocks are also overfished, and a third of freshwater fish species are considered threatened.

Climate change is a major contributor to the loss of biodiversity. The report gave the main cause for the dramatic reduction of genetic diversity as breeders selecting predominantly for varieties that are usable under the “widest possible” conditions. Commoditization of just a few varieties of food, and the consolidation in global seed markets among the “big four” seed and crop protection companies (Bayer/Monsanto, Dow/DuPont/Corteva, ChemChina/Syngenta, and BASF), both contribute to the lack of incentives to harvest more than a few staple foods.

The erosion of food diversity and genetic resources is dangerous for farmers, consumers and for the environment. The report shows that the genetic uniformity of crops makes them unable to respond to climate change and stimulates the rapid emergence of fungicide-resistant pest variants, which in its turn dramatically reduces productivity.

The report also mentions that, in China, the use of varietal mixtures of rice led to a 94 percent reduction of rice blast (a disease caused by a fungus) and an 89 percent increase in yields compared to monocultures. Agrobiodiversity boosts productivity and nutrition quality, improves the abundance of pollinators, increases soil and water quality, and reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers – thus significantly improving the environment. It also improves people’s immune systems and reduces inflammatory disease.

The erosion of food diversity and genetic resources is dangerous for farmers, consumers and for the environment.

One of the major challenges for introducing crop biodiversity lies in governmental policies. The 2019 report demonstrates that most countries require vendors to register the seeds of plant varieties before selling them. For registration, a plant must be distinct from other varieties, uniform in its essential characteristics, stable enough to not change when multiplied, and valuable for cultivation and use.

This system, originally implemented in Europe in the 19th century and designed to protect customers, no longer fulfills the needs of modern food systems. Instead of uniformity, we need variety in species, functionality and adaptability. To make that happen, we need to discuss policy change.

China and India: challenge and solution

Where does agrobiodiversity come from? Almost a century ago, the Russian scientist Nicolai Vavilov defined eight geographic areas that are the centers of origin of cultivated crop plants. The first and the largest center is China, with 138 distinct species, including soybeans, cereals, buckwheat, and legumes. India comes in second, being the origin of cultivated rice, millets, and legumes, with a total of 117 species. Indonesia and the Philippines represent a secondary center in the region – an origin of root crops, fruits, sugarcane, and spices (about 55 species).

The third-largest center is Central Asia, which is the origin of cultivated species of wheat, rye, sesame, and many herbaceous legumes, as well as seed-sown root crops and fruits (around 42 species). Iran and Turkmenistan represent the fourth-largest center, with about 83 species (including varieties of wheat, rye, oats, seed and forage legumes, and fruits). The fifth center covers the borders of the Mediterranean Sea and is the origin of about 84 species of plants (including species of wheat, barley, forage crops, vegetables, fruits, spices, and ethereal oil plants). Ethiopia and parts of Somalia are the sixth-largest center of origin, with around 38 species (wheat, barley, different grains, spices, and coffee). Central America (Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras) and South of Mexico comprise the seventh center, with around 49 species, including maize, spices, sweet potato, fruits, and fiber plants.

Finally, the eighth center is in the South American and Andes region (Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador), representing around 45 species of vegetables, spices, and fruits. South America has two secondary centers of origin: Chile, which is important for the domestication of potatoes (it has a total of four plant species), and Brazil and Paraguay, with a total of 13 species, including cassava and peanuts.

Facts & figures

As we can see, China and India are the world’s most important sources of agrobiodiversity, with China also holding the largest genetic crop bank. It is interesting that these are exactly the countries that face major challenges. Together they represent 36 percent of the global population, but their land is deteriorating and limited in availability, while their populations suffer from poor nutrition and poverty.

Moreover, the International Monetary Fund estimates that by 2030, China will account for 38 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, and India for 8 percent. In solving problems of food security, diet diversity and climate change, the world depends on this pair, and vice versa.

Scenarios

The UN Food System Summit and climate conferences later this year will consider a major policy agenda for agriculture and the environment. Agrobiodiversity needs to be an important part of these discussions, as it is vital for the transformation of the food systems and for the post-pandemic economic recovery.

With a record of almost $270 billion in green bonds issued in 2020, it is clear that governments and industry players are embracing green policies. Today, countries spend around $700 billion in agricultural subsidies, and this number is likely to grow as green policies demand more investments. Private financing mechanisms should also expand.

In the short term, the pandemic will continue posing a threat to public health and provoking economic constraints, disruptions in food production and trade, and rising food prices.

In the medium term, ensuring food and nutrition security for a growing global population will be an even bigger challenge. Countries are expected to try harder to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and will have to find a balanced approach to issues related to agriculture and the environment.

Within the next few years, the European Union and other countries will implement carbon border taxes and other environmental restrictions. These will hurt agricultural production and trade, posing major challenges for food and nutrition security.

Food systems will rely even more on technology and research. The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook projects that 87 percent of the increase in global crop production in 2030 will come from yield growth, while only 6 percent will come from expanded land use and 7 percent from increases in cropping intensity. Similarly, a large share of the projected expansion in livestock and fish production is expected to result from productivity gains.

Even though OECD-FAO estimates show an increase in global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 4 percent over the next decade (mostly due to expanding livestock production), the emissions per unit of output (carbon intensity of production) are expected to decrease significantly over the same period.

Demographic trends, urbanization and economic constraints are likely to impede major diet changes in the medium term. OECD-FAO data does not show an increasing variety of animal products, fruits and vegetables in the coming decade. Even though in many rich and middle-income countries, consumers are expected to substitute red meat with poultry and eggs – and with per capita dairy consumption in South Asia expected to grow significantly – diets in low-income countries are expected to remain largely based on staples. Fruits and vegetables are expected to continue to provide only 7 percent of all available calories.

A more positive long-term scenario depends on whether specific policies for increasing agrobiodiversity will be implemented – and international cooperation will be key to success. With the ongoing economic and technological decoupling, the West would have to find ways to work with China (and India), both on climate change and on the transformation of food systems.