Slovakia’s Fico will find it hard to emulate Hungary

Hungary and Slovakia share some tendencies under their controversial leaders, but when economic policies are compared, Slovakia falls short.

In a nutshell

- Slovakia and Hungary have similar political profiles, but different economic outlooks

- The leader of Hungary pulled his country out of a big economic hole

- The political veteran who returned to power in Slovakia may push it deeper into trouble

Viktor Orban is in his fifth term as Hungary’s prime minister and the fourth uninterrupted term since his party Fidesz won the 2010 national elections. He used strong popular mandates, on top of his undeniable political skills, to cement his power and bring Hungary out of the economic doldrums more than a decade ago.

Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico returned to power in 2023 also as a seasoned veteran, but he debuts as an outspoken critic and combatant against liberal democracy. He and Mr. Orban are strikingly similar in many ways but different in others.

Facts & figures

Factbox: Viktor Orban’s political milestones

- Hungary’s prime minister: from 1998 to 2002 and again since 2010; he is now the country’s longest-serving PM.

- Political party: president of Fidesz (originally the Federation of Young Democrats, subsequently Hungarian Civic Alliance) from 1993 until 2000 (when the party separated the posts of its leader and prime minister) and again since 2003.

- First term as prime minister: Mr. Orban’s conservative coalition moved Hungary in strides toward a free-market economy; it managed to lower inflation and fiscal deficits and presided over Hungary’s entry into NATO.

- Second term as prime minister: elevated again after Fidesz landslide parliamentary victory in 2010; spearheaded constitutional amendments that embodied conservative moral and religious themes, and curtailed the independence of Hungarian courts and news media freedom; that prompted accusations from the opposition and, increasingly, Brussels, of democratic backsliding.

- Reelections: in 2014, 2018 and 2022, the Hungarian hinterlands and the country’s expatriates repeatedly delivered decisive support to Fidesz and its leader in national elections; the opposition decried his constitutional reforms as limiting free and fair competition.

- Popularity of economic policies: European Social Surveys (ESS) show the Hungarians increasingly see Mr. Orban and his party as striving to improve the lot of working Hungarian families, creating jobs and asserting Hungarian interests internationally.

Prime Minister Orban claims to belong to the Christian center-right bloc, and Prime Minister Fico is supposed to be a center-left social democrat. However, some critics see both as having strayed far from these European political currents. In the European Parliament, Mr. Orban’s Fidesz has been expelled from the center-right European People’s Party (EPP), and Mr. Fico’s Smer was suspended from the social-democratic Party of European Socialists (PES). The two leaders, despite coming from rival political groupings, have become fast allies. Mr. Fico appears to be joining Mr. Orban’s quest against liberal democratic values and extending it to Slovakia.

Facts & figures

Factbox: Veteran populist

- Robert Fico (born 1964), Slovakia’s prime minister since October 25, 2023, served previously from 2006 to 2010 and from 2012 to 2018, for a total of over 10 years; leads the Smer-SD (Direction – Social Democracy) party he founded in 1999.

- “The burly and brash political veteran,” as The Guardian described him, is “typical of the new wave of nationalist-populist politicians who have emerged over the last decade, riding the wave of resentment generated among tens of millions of Europeans by the diverse disappointments of the third decade of the 21st century. His fall from power amid corruption allegations and after mass protests prompted by the 2018 killing of a young investigative journalist was supposed to be definitive.”

- However, five years later, Mr. Fico threw his hat in the ring of national elections again, campaigning on the need to cease military support to Ukraine and arrange peace talks with Russia. In the 2023 elections, Smer snatched the balloting’s most votes (29 percent) and 42 of the parliament’s 150 seats. Mr. Fico formed a coalition with two other nationalist parties and launched another term as Slovakia’s head of government.

Political similarities

Neither of the two men has been above resorting to populism and demagoguery in political practice. Their political records abound with maligning opponents, stoking fear and hatred, and deceiving, misleading and manipulating the public – in short, indecently stretching the powers vested in them under the rules of democracy. Until recently, however, there was also a significant difference: hard as he played to gain power, Mr. Fico had not crossed democratic boundaries to maintain it. Perhaps because of that restraint, he had lost office twice, in 2010 and 2020.

In Hungary, the drama was mainly due to mismanagement by two leftist governments formed by the Hungarian Socialist Party; in Slovakia, the blame goes in large part to Mr. Fico himself.

Now, he is ready to emulate Mr. Orban in that respect as well. Some factors augur against success: Mr. Fico does not have, and probably will not have, a supermajority of two-thirds of the votes in the Slovak legislature required to alter the constitution. Also, he has no equivalent of Mr. Orban’s ideology of a wronged and chosen nation, nor a large Slovak minority abroad to vote for him.

Hungary’s impressive turnaround

There appears to be a limit to the extent to which Mr. Fico is willing and able to make the necessary but often difficult and unpopular policy decisions that are critical for economic growth. And without growth, it is hard to retain power because circuses alone are not enough; one needs the bread too.

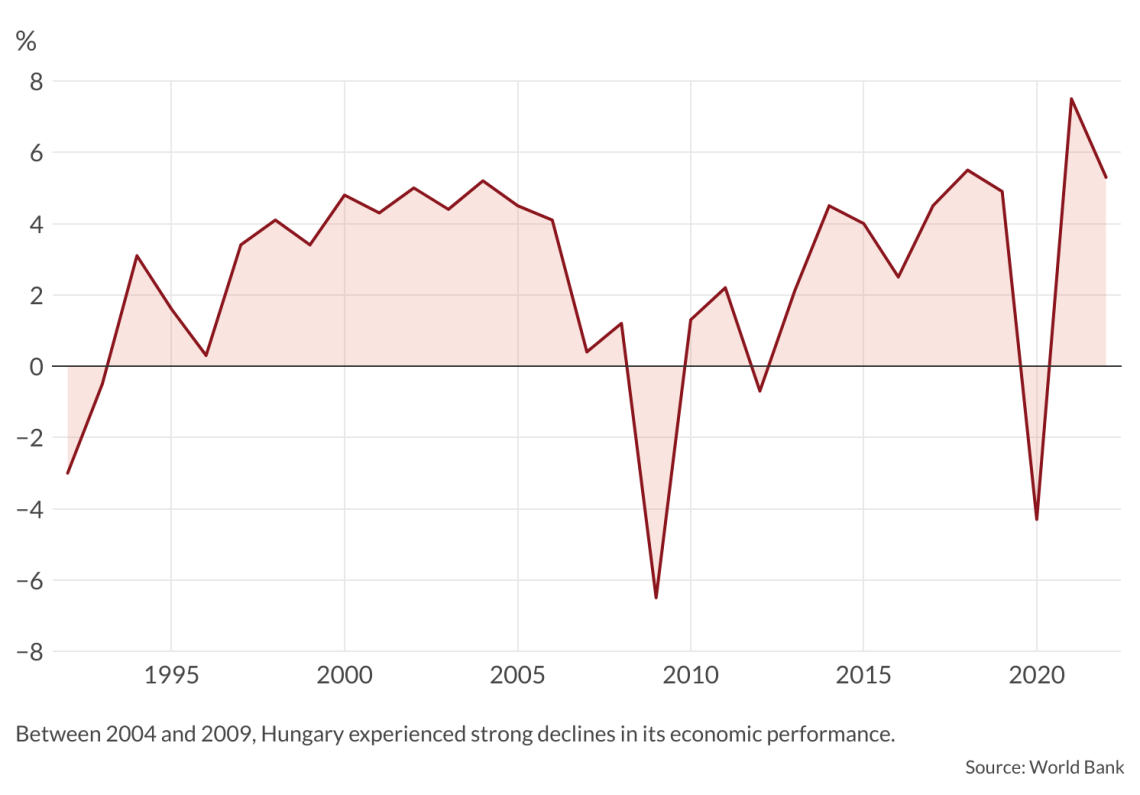

What Prime Minister Orban of 2010 and Prime Minister Fico of 2023 have in common (aside from the characteristics cited above) is that they took over economies in dire straits. In Hungary, the drama was mainly due to mismanagement by two leftist governments formed by the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP). In Slovakia today, the blame for the bad economic situation goes in large part to Mr. Fico himself, as he presided over its economic policies from 2006-2010 and 2012-2020.

Read more on the region

The Central European dilemma

Austria and Visegrad: Interests converge in Central Europe

The economic drama in 2010 Hungary was worse than it is in Slovakia today. After the 2008 global financial crisis that first wrecked the finances and then the economies of countries across Europe, Hungary’s public debt reached 80 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). At the time, the other Visegrad Four countries – Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – all had public debts about half as large.

Hungarian households were also the most indebted (over 41 percent of GDP, compared to about 30 percent for the Czech households and about 35 percent for the Polish ones). At the time, a significant number of Hungarian citizens carried personal loans, mostly mortgages, denominated in euros and Swiss francs, which they were unable to repay after the devaluation of the forint. More than two-thirds of Hungarians had no contingency reserves, social mobility declined and employment in 2010 sunk to 57 percent (it stood above 74 percent in 2022). While Slovakia’s per-capita GDP decreased by 1.3 percent between 2008 and 2011, Hungary’s shrank by almost 10 percent.

Facts & figures

Faced with this grim reality, Prime Minister Orban had to consolidate public finances and, at the same time, rehabilitate the overextended households, which was not an easy task. However, it was precisely in tax policy that Mr. Orban did exactly the opposite of Mr. Fico.

The Fico way

While Prime Minister Orban (in line with the recommendations of economists) was reducing the overall tax and levy burden, Mr. Fico was increasing it, and he now plans to ramp it up even more. While Mr. Orban was shifting the weight from direct to indirect taxes, Mr. Fico opted for the opposite strategy and is now staying this same course in 2024.

Prime Minister Orban raised the basic value-added tax (VAT) rate from 20 percent to 25 percent after he came to power in 2010 and to 27 percent in 2012. Since then, Hungary has had the highest base VAT rate in the EU. However, on Mr. Orban’s watch, the corporate tax went down from 20 percent to 19 percent in 2010 and to 9 percent in 2017 (the lowest in the EU). The country’s personal income taxes dropped from 36 percent to 18 percent and to a flat 15 percent between 2009 and 2016.

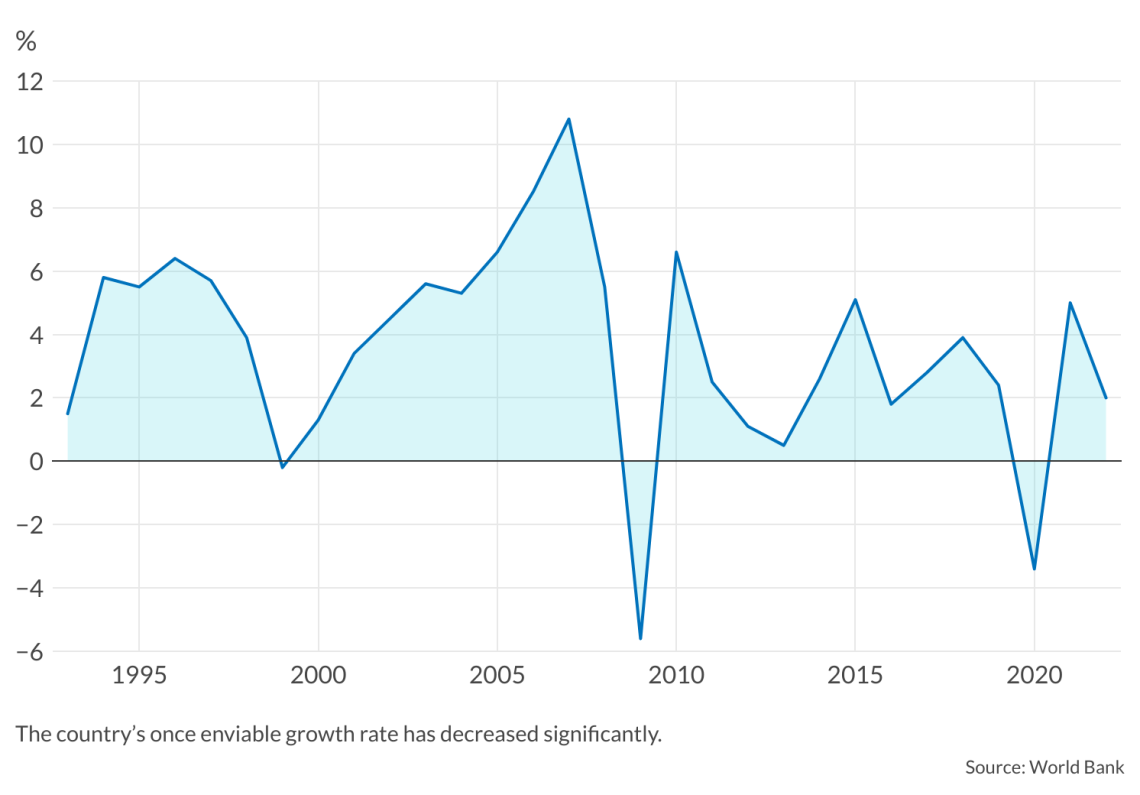

In Slovakia, taxes have increased over the same period, especially the direct ones. An earlier flat tax was abolished and labor taxes and levies increased, while VAT rates were reduced. The increase in the overall tax burden (relative to GDP) is reflected in the reduced growth dynamics of the country’s economy.

Facts & figures

While Hungary’s GDP per capita grew by 42.2 percent between 2012 and 2022, Slovakia’s grew at only half that rate (21.5 percent). Over the same period, Hungary’s total tax burden (taxes as a share of GDP) fell from 39 percent to 31.5 percent, while Slovakia’s tax burden rose from 28.8 percent to 31.5 percent. So, today, Slovakia has the same tax burden as Hungary, but a decade ago, it was more than a quarter lower.

The development of public debt has also been very different. While Mr. Orban reduced it from 80.3 percent of GDP in 2011 to 73.9 percent in 2022, Mr. Fico increased it from 51.8 percent in 2012 to 57.8 percent in 2020.

Slovakia also lags in investment. Between 2015 and 2022, the average annual share of total investment in Hungary was 26.9 percent of GDP; in Slovakia, it was only 22.9 percent of GDP. Add to this the fact that overall GDP growth was lower in Slovakia than in Hungary, and additionally, the difference in absolute investment volume is even greater, to Slovakia’s detriment. Consequently, Slovakia not only has a more significant debt burden but also lower economic growth prospects (which will be further dampened by Mr. Fico’s policies based on additional increases in direct taxes).

An important caveat

All of this is not to uncritically endorse Prime Minister Orban’s policies. Hungary’s democracy came under pressure from Mr. Orban as early as 2010, when he began advocating the dismantling of liberal democracy and replacing it with an “illiberal” variety of his design.

For the first time, Mr. Fico is starting his term in adverse economic conditions.

The dark side of illiberal and autocratic systems typically includes restrictions on competition, clientelism, corruption and harmful state interventions in pricing policy. The distorting effects of Mr. Orban’s economic populism can be seen in Hungary currently subsidizing household natural gas prices even more heavily than Slovakia. Fuel price regulations have led to confusion and shortages. Ultimately, these measures have contributed to Hungary’s inflation rate, which, at the end of 2023, was among the highest in the EU.

Corruption, too, is a significant problem for the Hungarian economy and society, which is hardly surprising, as Mr. Orban’s illiberal governance system effectively limits the government’s checks and balances.

The Hungarian prime minister may have wanted to emulate Singapore, which is also an illiberal democracy in the same group of “partly free” countries such as Hungary in the Freedom House rankings. But Mr. Orban has not succeeded as well. While Singapore is a singular example of a politically illiberal system with one of the freest economic systems in the world, Hungary has not made as much progress in applying this formula. Despite improvements on the tax freedom indicator, Hungary has deteriorated on such parameters of economic freedom as the protection of property rights, integrity of government and freedom of enterprise.

Scenarios

During Prime Minister Fico’s three terms, Slovakia fared worse. And now, for the first time, Mr. Fico is starting his term in adverse economic conditions. How will it end for Slovakia? Two base scenarios emerge.

More likely: Greece-style collapse

Prime Minister Robert Fico continues to dismantle the rule of law and attempts to consolidate his power while continuing to pursue populist economic policies to buy popular support.

Attempts to tackle the unsustainable situation in public finances by ramping up taxes on entrepreneurs and high-income groups lead to tax evasion, corporate migration and brain drain, and sharp reductions in investment and growth. As public debt continues to balloon, the government is forced to borrow still more expensively, heading toward insolvency.

The decline in the quality of public services and meager growth undermine standards of living, inevitably sapping Mr. Fico’s political strength by the time of the 2027 elections. His party is defeated.

Less likely: Policy change after presidential elections in 2024

In the spring 2024 presidential elections, former Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini, the leader of Slovakia’s second-strongest coalition party (who defected from Mr. Fico’s Smer in 2020 and founded Voice-Social Democracy, a left-leaning nationalist party), will run for the presidency. The new party led in the polls between 2020 and 2022, but Mr. Fico’s Smer rebounded and won the September 2023 balloting, dashing Mr. Pellegrini’s hopes of a second premiership. At present, the current prime minister supports his former rival’s presidential bid, probably assuming that Smer could then easily “swallow” Hlas by luring its deputies to change affiliation.

It is, however, doubtful that the contest will reverse the country’s economic policies, because both politicians consider their continuation as necessary to win. It is also unlikely that the government opts to change things after the presidential election.

Little in Mr. Fico’s record in power suggests that he can summon enough political courage to introduce the obvious but (in the short term) unpopular economic policy corrections. Prime Minister Orban managed to do that, but he had an insurance policy at the time – a constitutional majority wide enough to guard against losing power. Mr. Fico is in a more precarious political position.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.