France needs to rehabilitate its African policy

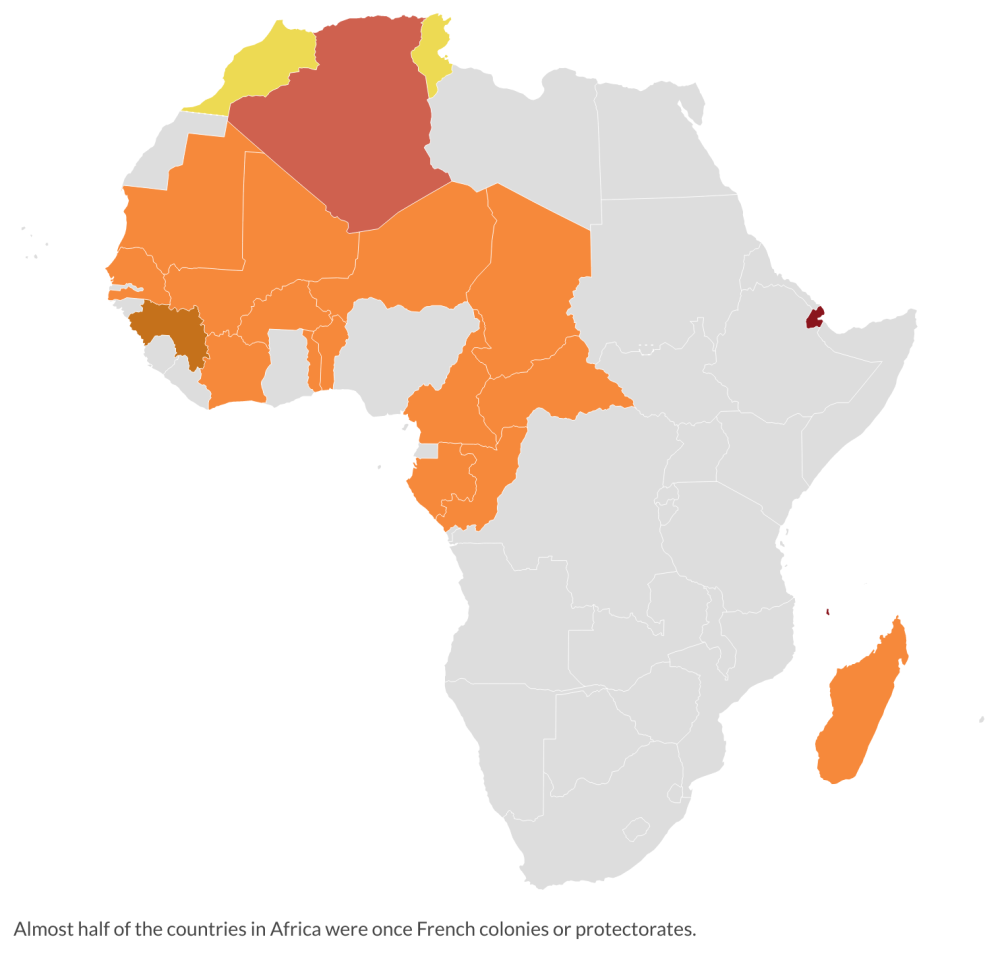

An increasing number of countries in Africa are cutting long-standing security ties with France out of disappointment with Paris’ handling of issues important to the continent.

In a nutshell

- France’s influence in Africa is waning

- Paris has made crucial diplomatic mistakes

- A new African policy would benefit both sides

In 2022, Africa turned its back on France. African countries have cut long-standing ties with Paris, turning instead toward the British-led Commonwealth. Local populations held protests demanding the departure of French troops and clamoring for Russian Wagner commandos instead.

In parallel, other world powers are attempting to increase their influence on the African continent. Turkey is mobilizing to carry out infrastructure work at very competitive prices. Turkish companies built the new airport in Dakar. China is investing in most African countries via financial institutions created for this purpose, in particular the Exim Bank and the China Development Bank. Brazil, India and Pakistan are also trying to develop closer economic ties with African countries.

Crucial mistakes

France has lost the privileged relations it had 30 years ago. This is a result of movement and trade liberalization, but also the outcome of clumsiness and serious mistakes on the part of the French authorities – for example, ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy’s disastrous 2007 speech in which he declared that “the African has not fully entered into history.’’

More recently, President Emmanuel Macron was reduced to discussing the future of Africa with associations and students in Montpellier instead of doing so with African heads of state. For a long time, the Africa-France summits were the traditional platform where all the presidents of French-speaking Africa met with the French president, where relationships were forged among the participants, where burning issues could be discussed and solutions found. Gone are these privileged meetings.

Even countries where France is still considered an ally are beginning to have doubts.

A serious mistake was made during the 2011 Arab Spring with the intervention in Libya, organized by former President Sarkozy against the advice of African leaders, which led to the overthrow and death of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. The upheaval caused total anarchy in Libya. Armed Tuareg soldiers who had been mobilized by Qaddafi returned to the Sahel region and joined jihadist or rebel movements.

It was also a mistake to have allowed a former foreign minister of Rwanda, Louise Mushikiwabo, to be appointed Secretary General of the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF). Rwanda has renounced French as a first language, has joined the Commonwealth and has been conducting a relentless propaganda campaign against the French army for more than 20 years.

Facts & figures

Unfortunately, this succession of errors has gradually created a climate of mistrust and even violent ruptures between France and French-speaking African countries. The Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali have requested the departure of the French ambassador and French troops – troops that had been called in to help and who fought and died to contain the jihadist threat. Bangui and Bamako turned to Russia, welcoming Wagner commandos on their territory. They now provide security for government authorities, certain localities or provinces and are paid through the exploitation of mines, notably gold in Mali and diamonds and uranium in CAR.

High stakes

Even countries where France is still considered an ally are beginning to have doubts. Togo and Gabon joined the Commonwealth last July. Niger and Chad are paying a high price for the implosion of Libya. Libyan militias and armed gangs are pouring into their territory and destabilizing local politics.

Worse, a few years ago, allies such as the United Kingdom and the United States intervened in the French-speaking world, often after consultation with Paris. Since the war in Rwanda and the violent troubles in Kivu, a rich province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a gap has widened between France and the Anglo-Saxon countries. Washington and London still imply that France was complicit in the monstrous genocide in Rwanda.

Today, some voices are being raised in France to try to shed light on this region of the world where a war is being fought over the exploitation of crucial raw materials, like coltan and cobalt. Human beings, especially women and children, are being trafficked there with full impunity and to the greatest benefit of Anglo-American, Canadian and South African financial and mining companies.

It is urgent that France redefine its African policy.

The economic stakes are high; these metals are necessary to produce semiconductors, cell phones and communication networks as well as military systems and missiles. The issue is so vital that the U.S., which has long been closely linked to the Rwandan and Ugandan governments, became directly involved to the point of concluding, during the first Kivu war, the secret agreements of Lemera with the Congolese rebels. This was later revealed by President Laurent Kabila himself, and facilitated the creation of an American-Rwandan company for the purpose of regulating, or even controlling, the trade in rare metals.

Different approach

It is urgent that France redefine its African policy. The friendship and ties that Paris has built over time with Africa, with its political, economic and thought leaders, justify doing everything possible to build new cooperation in all sectors: culture and education; health and pharmaceuticals; energy and mining; agriculture and food industry; transportation and infrastructure.

This new policy must not allow itself to be guided and stifled by Brussels’ technocratic approach. France must reinvest in the OIF and help the organization coordinate all cultural and educational interventions in the French-speaking world. This requires a political approach after having determined the goals to be pursued: universities, education, book policy, support for the film industry, social networks. Under no circumstances should the OIF be reduced to a bureaucratic body or worse, to a Trojan horse. Governments should commit to handling OIF matters at the ministerial level. And the organization’s council ought to be composed of presidents or heads of government instead of administrators only.

France must have the courage to address the issue of immigration with all the French-speaking countries of Africa. It must have privileged relations with these countries which will result in a visa policy welcoming migrants from Africa for specific purposes like training and employment.

France’s Africa policy must once again become rooted in cultural influence, loyalty and first and foremost, shared history.