France’s politics of mistrust

France’s latest legislative elections have shown that a majority of voters have lost faith in mainstream politics.

In a nutshell

- The president’s party has lost its majority in the National Assembly

- The latest elections reflect long-standing resentment toward the political elite

- This climate will make it hard for France to solve its economic woes

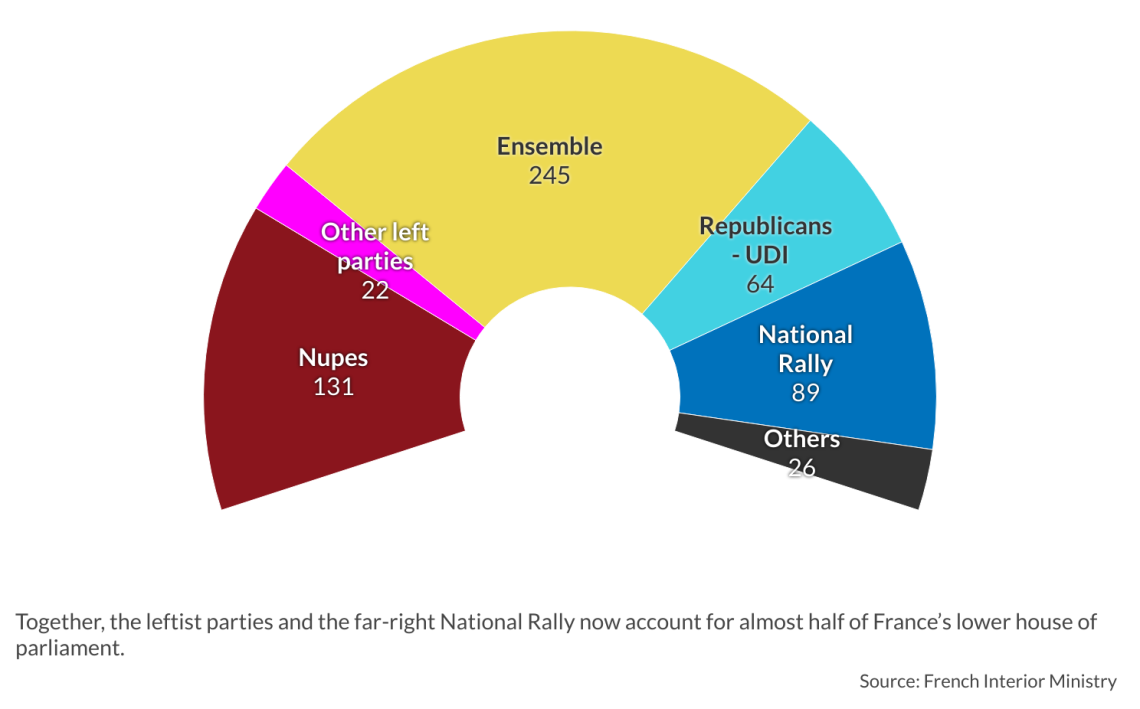

A few weeks after the presidential elections, France’s legislative elections produced a strange outcome. While Emmanuel Macron was reelected as president in April, the June election of National Assembly lawmakers – the lower house of parliament – did not give President Macron’s Renaissance (formerly La Republique en Marche!) an absolute majority. The party did not win the necessary 289 seats, receiving only 245 out of 577.

The results of this last election have demonstrated the increasing importance of three groups: the far right (Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, which went from eight seats to 89), the far left (NUPES, a gathering of socialists, environmentalists and communists, with 131 seats) and those who abstained from voting (52 percent of the population, 70 percent in the 18-24 age group). Together, they make up three-quarters of the electorate, and are perceived as “against the system.” Several observers, while noting the National Assembly has become “more representative,” were shocked by this level of mistrust toward traditional politics.

The reason why so many citizens do not trust the system may be that French politics is traditionally president-centric, and as a result less democratic and more technocratic. Some would thus say that more political parties in the National Assembly make it more democratic. However, democracy is much more than just how well or poorly political views are represented. It is, above all, accountability.

Under a political system with little accountability, more demands for public spending fueled by envy and social anger could rapidly spiral out of control. Given the massive challenges that loom over the country, French politics could get messy in the near future if radical reforms have to be decided upon collectively in an emergency.

Land of mistrust

Mistrust in French society has historical roots, and results from an institutionalized lack of accountability and transparency.

For more on the causes of French mistrust:

France and the sociology of bad governance

The gradual construction of the French state was based on “divide and rule” politics. The egalitarian Republic eliminated intermediary bodies. The elitism that comes with the centralization of power de facto places politicians above the population, limiting genuine democratic accountability. Meanwhile, corporations compete for (and cling to) “privileges” granted by the state and paid for with taxpayers’ money – all this in a context of fiscal illusion. The country’s hybrid constitution has gradually strengthened presidential powers, weakening other bodies and eroding accountability.

More recently, the Yellow Vest protests were spurred by Mr. Macron’s policies and “hyper-presidential” attitude. The Covid-19 crisis aggravated perceptions of the president as an aloof and arrogant leader, especially when he declared his intention to “piss off” unvaccinated citizens. His reforms were imposed from the top, in a very technocratic manner; ad hoc “citizens’ conventions” were established to create a false sense of democratic decorum. No wonder popular resentment and disappointment grew stronger, leading voters to abstain or choose extremist parties.

Representative unaccountability

In theory, more parties in parliament can provide a system of checks and balances to counteract presidential power. More “democracy” in the National Assembly will force the president and his government to be less technocratic. But will that lead to better governance?

Many hope that Mr. Macron’s so-called “liberalism” can be contained. In reality, his reforms were never liberal. Public spending (61 percent of gross domestic product), debt (114 percent of GDP) and deficits (6.4 percent of GDP) exploded during his tenure. His few “liberal” promises, like a serious reduction of public spending, never materialized. One could blame Covid-19, but the spending trend in France long preceded the pandemic, while other comparable countries have since made efforts to rein in their public finances.

It seems France only plans to increase its spending. A more representative parliament does not mean a more accountable one as long as fiscal illusion remains. Radical left and right groups want more of “other people’s money.” NUPES’s social emergency bill, with a 1,500-euro monthly minimum wage, price controls, increase in civil servants’ pay and a 25 percent tax on “superprofits,” is a good example. The Finances Commission of the National Assembly is now held by the far left. Many fear an upcoming spending spree. The president felt it necessary to declare that the government should be careful with public spending. Minister of Finance and the Economy Bruno Le Maire stated that “public finances have reached a critical level.”

Facts & figures

Cracking the “Republican Front”

In the 1980s, President Francois Mitterrand evoked the necessity of a “Republican Front” to protect France from the rise of the far-right Front National. Left and center-left candidates would withdraw in favor of a center-right candidate, and vice-versa, against populist Front National candidates to neutralize them during the second round of elections. Voters would most often follow, as in 2017 with Mr. Macron’s first election. The center thus short-circuited the possibility of Front National elected officials, thereby leading to a representation imbalance.

During his first term, President Macron benefited from this strategy, and the National Assembly was effectively at his beck and call. Today, the “Republican Front” has cracked for the first time, with a major group of Le Pen representatives at the National Assembly. Far-left populism, whose views are close to that of the far right except when it comes to immigration and Islam, has also gained traction.

However, their own party’s plan to support purchasing power mirrors the propositions of the extreme right and left – some 20 billion euros. Civil servants will receive a 4 percent pay raise. At times of inflation (5.8 percent year-on-year in June) such a plan is necessary. But no credible plan to rationalize spending has been put forward to compensate. (Pension reforms will be discussed this fall.) Moreover, the electricity company EDF will be fully nationalized to save it from bankruptcy, costing an extra 9.5 billion euros. In January, Mr. Le Maire dismissed the European Union’s debt and deficit limit rules as “obsolete.” France’s Audit Office recently criticized the government’s “optimistic” forecast of a 5 percent public deficit at the end of the year.

Facts & figures

Worrisome trends

At 114 percent of GDP, France’s official public debt is rocketing. The Covid-19 crisis contributed to this state of affairs. However, faced with the same issues, Germany managed to limit its debt to less than 70 percent of its GDP. In six months, France’s rates on its 10-year bond jumped to 2.2 percent. Each percentage point costs an additional 40 billion euros. Worse, 12 percent of the issued bonds are indexed to inflation, thus increasing the cost of borrowing for the French government (17.5 billion euros this year). In addition, European Central Bank policies to combat surging inflation through higher target interest rates and the end of repurchasing programs of government bonds will push borrowing rates up even more. Debt will become increasingly costly.

In this already gloomy context, French growth is very sluggish, and will be limited to 1.5 to 2.2 percent this year. Clearly, the post-Covid rebound effect is gone. This means less tax revenue for the government, and more difficulty to pay off its debt. Given energy issues linked to malfunctioning nuclear reactors (29 out of 56 reactors had to stop operating during the summer), electricity shortages are possible, affecting growth even more. It is unclear how the government will pay for the promised six new nuclear reactors while also trying to rescue EDF. While the country was supposed to become a hub for foreign investment with Mr. Macron’s Choose France program, it still ranks 35 out of 37 OECD countries (according to the Tax Foundation) in terms of tax competitiveness, and its trade deficit is growing.

Scenarios

Twelve years ago, during the global financial crisis, Greece’s debt was 300 billion euros. France’s debt is 10 times this figure – and this is after the ECB exhausted its ammunition. Clearly, a functioning and accountable French democracy is needed to solve the imbroglio.

For comparison, when Sweden was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1992, the population was presented with options to create a consensus on what public services were to be prioritized and about the benefits granted to civil servants. The answers were rational, and so was the country’s response.

However, Sweden was a mature democracy with a high degree of trust and extensive social dialogue. France has none of these things. Its civil servants (a fifth of the active population) are entitled to strikes, unions and lifelong jobs: they will not renounce their privileges. Frustration and mistrust among ordinary people are immense, as shown by the Yellow Vest movement or the legislative elections. And now the new “more representative” parliament includes even more spendthrift politicians.

Two paths are facing the country in light of the inescapable debt shock to come.

Accountability shock

Under external pressure, the political class reacts by rapidly switching to a more accountable model (with a radical reduction in fiscal illusion), one that naturally generates better governance. A new and transparent framework for accountability, one that enables social compromises, is put in place. The population, aware that the situation is critical, accepts this new paradigm despite the loss of special benefits, and the debt crisis is overcome. This, however, would require a stark departure from the current situation.

Status quo

Given the level of mistrust, vested interests and the lack of democratic maturity and peaceful social dialogue, the country is not able to evolve in such a short time. The sovereign debt crisis turns sour. The ECB tries to intervene once again but cannot solve the issue because of the size of the French debt. French society destabilizes, with repercussions for the whole of Europe and the eurozone. The violence of the Yellow Vest protests would appear insignificant compared to what would come to pass under such a scenario.