France and the sociology of bad governance

In France’s ideal republican model, the enlightened elite lead the public toward a unified, egalitarian system. The model is corrupted, however, with some “more equal” than others. The resulting lack of accountability creates a dysfunctional French governance system.

In a nutshell

- France’s Republican ideal has been corrupted

- A lack of accountability causes governance problems

- Centralization breeds distrust within the system

This new series of GIS reports examines how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies and nations’ development prospects.

To understand French governance, one must first look at a historical factor that gradually shaped its overarching political ideology: the concept of the Republic. There is no doubt that the French Republican model brought some progress in advancing the common good on several accounts (notably in the late 19th century). However, its impossible ideal – both elitist and egalitarian – has been corrupted, producing hybrid systems at the political, administrative and social levels that have become the very opposite of good governance.

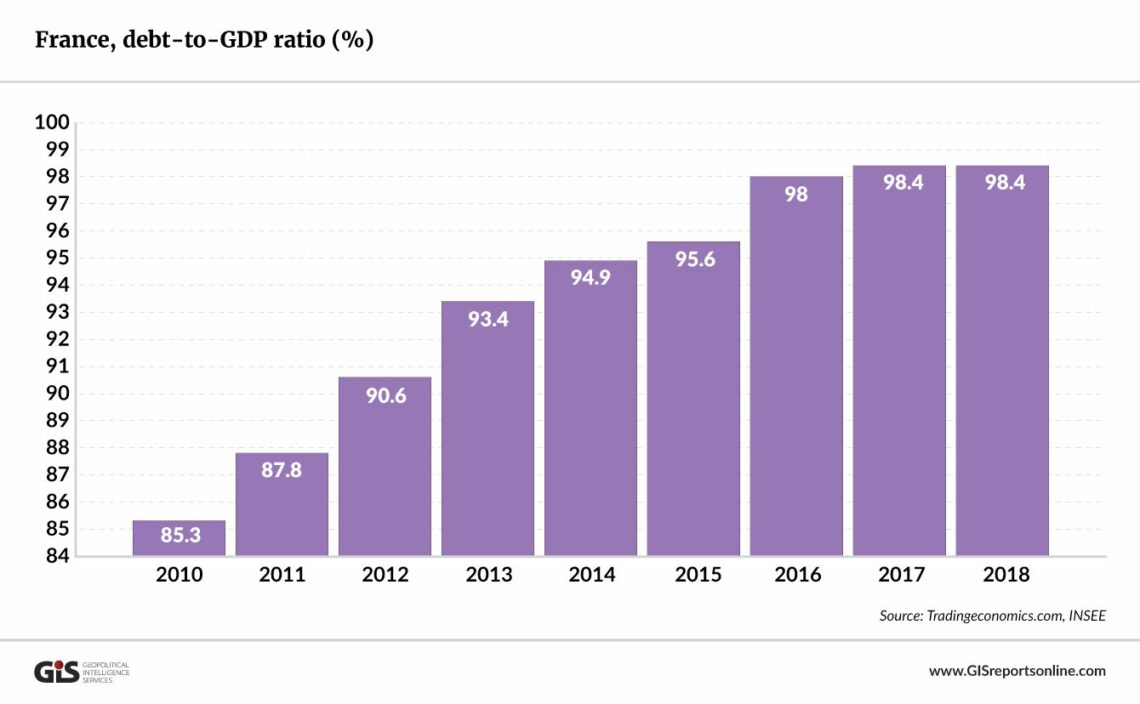

Good governance presupposes sound social consensus-building processes that rely on political accountability. France has neither, which may be the reason for its disastrous figures in terms of spending, debt and unemployment.

Central elite

As British historian Robert Bates points out, France’s central authorities have been obsessed for a millennium with somehow rebuilding Charlemagne’s lost empire and then avoiding another tearing apart of the Grande Nation. For centuries, French governments have used intimidation and divide-and-rule tactics against local authorities to gradually build up a powerful, reconstituted state.

Within the French republican model, an enlightened elite guide the people toward the common good.

The price for this restoration has been centralism, which by its very nature does not abide autonomy below it. The corollary is mutual distrust between central and local authorities – a major obstacle for a mature democracy.

The French Republic is the latest incarnation of this centralism. Within the French republican model, the enlightened elite guide the people toward the common good.

This pretense of knowledge naturally tends toward universalism: the French consider their model (especially embodied in the rights of man and of the citizen) as so perfect that it is destined to encompass all.

Facts & figures

French governance: History and structure

France is a semi-presidential republic comprising 18 regions (13 metropolitan regions and five overseas). It has had many constitutions, the current one having been in place since October 4, 1958. It uses a civil law system with review of administrative but not legislative acts.

Executive branch

The President of the Republic is the chief of state and is directly elected by an absolute majority popular vote in two rounds (if needed) for a five-year term. The president is eligible for a second five-year term.

- The Prime Minister is the chief of government and is appointed by the president

Legislative branch

France has a bicameral parliament.

- The Senate has 348 seats. Members are indirectly elected by departmental electoral colleges using absolute majority vote in two rounds if needed for departments with one to three members and proportional representation vote in departments with four or more members; members serve six-year terms

- The National Assembly has 577 seats. Members are directly elected by absolute majority vote in two rounds if needed to serve five-year terms

- The last elections for the Senate were held on September 24, 2017; the next will be held on 24 September 2020. The last elections for the National Assembly were held on June 11 and 18, 2017; the next will be held in June 2022

Judicial branch

- The Court of Cassation consists of the court president, six divisional presiding judges, 120 trial judges, and 70 deputy judges organized into six divisions - three civil, one commercial, one labor, and one criminal); The Constitutional Council consists of nine members. These are France’s highest courts.

- Court of Cassation judges are appointed by the president of the republic from nominations from the High Council of the Judiciary; judges are appointed for life. For the Constitutional Council, three members are appointed by the president of the republic and three each by the National Assembly and Senate presidents; members serve nine-year, nonrenewable terms with one-third of the membership renewed every three years

- Subordinate courts include appellate courts; regional courts; first instance courts; administrative courts

- In April 2018, the French government announced its intention to reform the country’s judicial system

Republic vs. democracy

The Republic seeks unity in equality and thus rejects differences in smaller communities. The citizen is “raised” by the state, and the latter is suspicious of intermediary bodies. The state is also distrustful of genuine democracy and is therefore responsible for the central power’s lack of accountability. By definition, the people cannot hold the knowledgeable elite accountable.

Facts & figures

The enlightened elite end up hiding certain decision-making factors from the citizens. The extensive use of fiscal illusion is evidence of this. From very complex pay slips to less than 45 percent of households having to pay income tax and now only 20 percent paying the housing tax, these methods hide the true cost of social security and government.

No wonder French President Emmanuel Macron argues that the European Union’s deficit rules “belong to another century.” Debt is a wonderful instrument of fiscal illusion. (Maybe new European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde will help Mr. Macron in his sleight of hand.) This intentional lack of transparency – which goes back at least as far as 17th-century French Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert – also impedes accountability.

The elite typically refuse popular choices that run counter to their thinking. A prominent example is the French people’s rejection of the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties, and the French government finding ways to implement them anyway. French philosopher Chantal Millon-Delsol points out that in the French Republican model, democracy must be constrained within the ideological boundaries set by the Republic, to avoid the dangerous wanderings of popular opinion (an admission of its failure to enlighten the masses). The tension between the Republic and democracy is clear.

Hybrid systems

Philosopher Jean-Francois Revel’s profound analysis demonstrates how the Fifth Republic (after 1958) makes things even worse. Tailored for one man, General Charles de Gaulle, its constitution was unfit for his successors. It is a hybrid between parliamentary and presidential systems. The parliament is weak and the prime minister, who plays the role of a “circuit breaker” when things turn bad, protects the president from responsibility. The basic condition for democracy – political accountability – is therefore absent.

Far from generating an ‘efficient absolutism,’ this lack of democratic control generates bad governance.

Far from generating an “efficient absolutism,” this lack of democratic control generates bad governance. It is a “presidential monarchy,” as Revel put it, that destroys the connections between decision, execution and responsibility. Below the president, the fear of making decisions that could displease the monarch – and destroy one’s ambitions – is incapacitating. Talent is wasted and the strong, stable executive is unable to govern properly.

The one action that is undertaken without any problem is spending. To exist bureaucratically and politically, one must follow the motto: “I spend, therefore I am.”

The French Parliament is weak not only due to how the constitution sets out its structure and responsibilities, but also because politicians can hold multiple offices, with local interests conflicting with their mission of supposedly defending the national interest in parliament. They do not have the time to properly do their job of overseeing the government and its administration. Many of them come from the administration itself, which represents another conflict of interest. (In 2017 reforms were implemented that made it harder to hold multiple offices.) The French national audit office (Cour des Comptes) produces wonderful reports but, unfortunately, has no power.

The French administrative system is also a hybrid, which one might name centralized decentralization. Local governments are dependent on the central government for their endowments. Without fiscal autonomy it is difficult to have fiscal accountability. The proliferation of new decentralized entities has given rise to a complex administrative layer-cake, with various financial flows and in which each layer has an incentive to spend as much of other people’s money as possible to please its constituency or bureaucratic clientele.

Crony republic

This lack of accountability is duplicated in the economic realm by political interference in big companies: another hybrid system. This crony capitalism has far-reaching consequences for those firms. The banking sector is an obvious candidate, with executives too often coming from various government ministries. Dexia, the Belgian bank that supported French local governments, is a perfect example. Due to its catastrophic management, it was bailed out in 2008 and 2011 and ended up costing the French and Belgian taxpayers more than 8 billion euros. Its board was filled with French politicians who were supposed to provide proper governance.

Areva, the former French nuclear company, is another illustration of bad corporate governance: with Anne Lauvergeon at its helm, it piled up mistake after mistake. It even bought a dodgy company, UraMin, for its mines, which Areva’s own engineers had warned were empty. Taxpayers recapitalized the company to the tune of 5 billion euros in 2017.

Ms. Lauvergeon said she had been brought in because the company needed “a strong and dynamic personality,” but she was also exceptionally well-connected. She was a close advisor to former French President Francois Mitterrand and graduated from some of France’s most prestigious schools: Ecole des Mines and Ecole Normale Superieure. Belonging to the Republic’s elitist circles makes one almost untouchable, and unaccountable.

More equal

It is hard not to see a link between the French Republic and its cousin, socialism. Like its cousin, it has the same internal contradictions. In the egalitarian Republic too, some end up being “more equal” than others. The case of the elite is obvious: their privileges range from less trouble with tax officials to special housing access. Curiously enough, the Republic is not a big fan of pension funds (so Anglo-Saxon!), but its civil servants have the right to enjoy one. All sorts of special fringe benefits can be enjoyed by the more equal class. Clearly, such privileges benefit neither governance nor social trust.

A central ideal of the Republic is that of republican virtue. Yet there is a significant number of politicians, even at the highest levels, who are dogged by scandals. Then again, this is to be expected from a class that is above the people.

While low-level civil servants do not have much autonomy, they also frequently lack motivation.

Moreover, while low-level civil servants do not have much autonomy, they also frequently lack motivation. The old cliche of the zealous Republican schoolteacher no longer rings true. This is the result of bureaucratizing public missions. Here too, virtue has been corrupted.

The Republican elite have also had to deal with a new competitor, especially after World War II: far-left unions. The success of the Communist Party gave it the leverage to impose trade union regulations on various aspects of work life. While they now represent less than 7 percent of the working population – mostly in the public sector – unions still have enormous power, as recent strikes have demonstrated. The entitlements that the unions were able to obtain for the professions they represented are not in line with Republican equality.

There were some other professions, like lawyers, who were happy to remain outside of this structure and still secured robust pension systems. In the unionized sectors, however, taxpayers have had to fund extraordinary fringe benefits for decades. So the French welfare state is centralized but has corporatist asymmetries and is therefore not equal nor “Republican.” It is yet another hybrid system.

The system remains conservative, thanks to the benefits so many receive. People do not want to change. Various corporations compete for favors, with the government always the central decision maker, like a parent distributing candies to competing children. Mistrust has therefore also spread horizontally, across society.

That is the story told by economists Pierre Cahuc and Yann Algan about the French welfare system. But the story about the lack of trust was already told by Alexis de Tocqueville in the 19th century, and again by former government minister under de Gaulle, Alain Peyrefitte in the late 20th century. Without social trust and solid social capital, it is difficult to expect good governance. When the model itself generates mistrust and hides information, fostering debate becomes impossible, and therefore so does consensus building. The so-called “national debate” initiated by Mr. Macron after the Yellow Vest movement erupted was just another centralized attempt to replace genuine democratic debate.

Two (and a half) options

There are two ways to make such hybrid systems more coherent. The first is a more democratic option, based on diversity, subsidiarity and accountability of all government levels. This requires clarifying the roles of the parliament, government and the president so that they have more transparency and responsibility. This also includes genuine financial and decision-making autonomy for local governments, as well as of open but financially responsible welfare options for individuals, social groups or corporations. This would work to increase political maturity at all levels. However, the risk of losing national cohesion could increase: regions like Brittany or Corsica may push harder for autonomy. This more democratic option is not compatible with the Republican order.

The second option is the genuine Republican one, with its enlightened, technocratic elite leading the plebes toward a more unified Republic and egalitarian system. This may be the solution President Macron has been trying to implement for the past year and a half.

Two examples highlight this possibility. First, the reduction of financial endowments to communes (France’s lowest administrative division) and the gradual elimination of the housing tax (an important source of revenue for the communes) have severely affected local finances. At a meeting with angry mayors, President Macron even called himself the mayor of “Commune France,” again emphasizing the preeminence of the central state. Such moves smack of countering decentralization.

Second, the latest pension reform moves in the same direction. It amounts to a nationalization (and thus an equalization) of pension schemes and mirrored the nationalization of unemployment schemes implemented earlier in Mr. Macron’s term.

Scenarios

Will a return to a purer Republic be enough to improve French governance? Hard reality will never allow for the ideal to be achieved, even with corrections from time to time. Moreover, imposing a centralized system today seems completely at odds with the arc of history. The world is becoming more decentralized, with local solutions that require more autonomy, subsidiarity, institutional flexibility and variety. In this context, the old ideal of a centralized unitary Republic with its rigid, bureaucratic framework seems counterintuitive. The option could be plausible if it was applied to a minimal state apparatus, but not the gigantic French bureaucracy.

Maybe President Macron is trying to put the Republican house in order before attempting reforms aimed at more democracy, autonomy and responsibility. Yet, as Revel said, enlightened despotism is rare. Moreover, it appears the Fifth Republic’s fundamental structure will not be altered, nor the central political hybrid unwound. There is no sign that the absolutism will become more efficient.

Elections will make things worse, forcing the executive to backpedal on Republican ideals. The cycle will continue. In France, republic and democracy will undermine one another – and governance will continue to suffer.