A state in limbo

In Syria, large parts of the country are half-empty and loosely controlled by the government. The remaining regions are self-ruling principalities, each under a different force. Al-Assad’s regime continues blocking opportunities for peace – to the detriment of Syria’s future.

In a nutshell

- Large parts of Syria's territory are outside government control

- Sanctions and crime are severely crippling the Syrian economy

- President al-Assad, supported by Russia and Iran, is blocking compromises

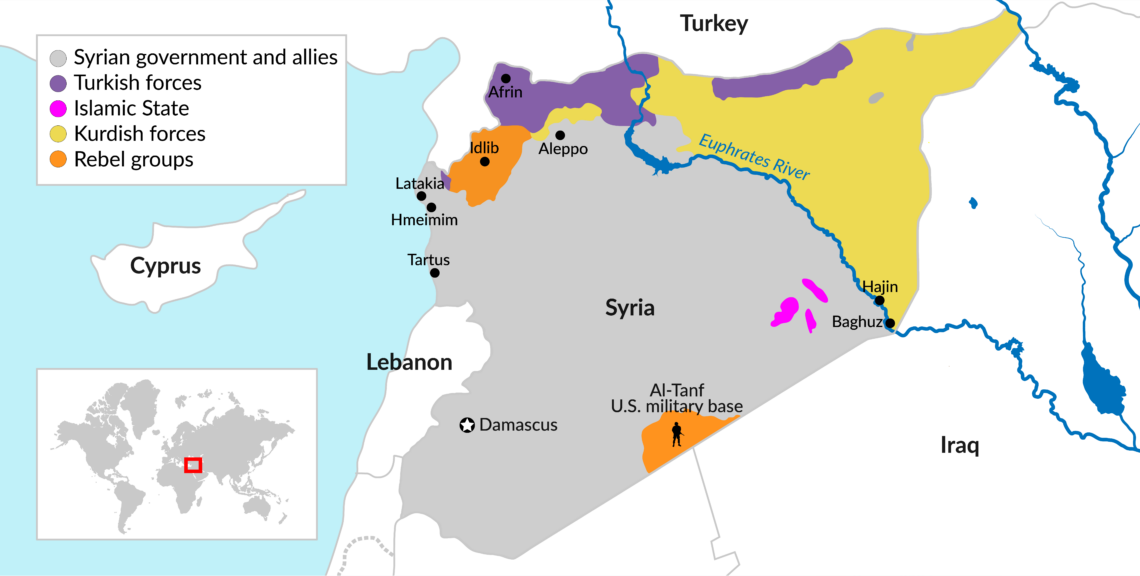

In today’s Syria, there are five main forces at odds with one another. They occasionally exchange fire, and some of these camps are split into factions that also shoot at each other from time to time. This has been the status quo since 2018.

First, there are the Syrian regime’s military forces and its loyalist militias in the central and eastern parts of the country. They are backed by tens of thousands of Iranian-backed Iraqi, Lebanese, Afghan and Pakistani Shia militiamen, controlled by a few hundreds of officers from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. Then, there are Russian troops in the west, on the coast, and Turkish troops and pro-Turkish Syrian militias in the north. Kurdish forces also operate in the north and northeast, supported by some 500 United States troops and its air force. Finally, in the south, in Al-Tanf, at the junction of the Syrian, Iraqi, and Jordanian borders, there is an American force of 200 to 300 troops. With air support, they are preventing Iranian military transports from Iraq into Syria, then Lebanon.

In addition to the main players, Islamic Sunni rebels are active in the northwest, Islamic State is stirring in the east and the Israeli military is performing aerial incursions over most of Syria.

Frozen in a time capsule, the Syrian state is awaiting resurrection.

If we apply Max Weber’s definition of the state as an entity that has a monopoly over violence, then there is no Syrian state. And, looking at the present demographic situation, it would be possible to argue that there is no Syrian nation either. In 2011, there were between 21 and 22 million Syrians. As of March 2021, opposition groups’ estimates of the number of deaths in the Syrian civil war vary between 388,650 and 594,000. Between 6 and 7 million fled the country. In addition, some 5 to 6 million Syrians are internally displaced. This means more than half the Syrian nation have become refugees.

Given the above-mentioned disruption, there is no Syrian economy either. Some could therefore come to the conclusion that there is no Syrian state. The center and south of the country are half-empty and loosely controlled by the government and its affiliated foreign militias, while the remaining territory is split into self-governing principalities, each under a different force. And yet, on the shoulders of two giants, Russia and Iran, President Bashar al-Assad’s regime is hanging on. Frozen in a time capsule, the Syrian state is awaiting resurrection.

Facts & figures

Syria’s Alawites

While there is no reliable demographic information available at the present, demographic surveys before the civil war show that the majority of the Syrian population, around 65%, are Sunni Arabs. Approximately 10% are Christian. Sunni Kurds represent around 7%. Some 2-3% are Shia Muslims and another 10% belong to the Alawi sect, a distant offshoot of Shia Islam.

During the first decades of Syria’s modern history, the Alawites were an underprivileged minority, but through their supremacy in the military, since 1966 they have been ruling Syria. The 1970 internal Ba’ath coup that brought Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, to power, turned them into an unchallengeable ruling elite.

Source: Prof. Dr. Amatzia Baram

Ongoing conflicts

Idlib

The main conflict of the al-Assad regime is its fight against Sunni extremists over the rebel-held province of Idlib in the northwest, though there are small-scale confrontations elsewhere too. Most Idlib insurgents are loyal to Turkey, their only defender. One ultra-extremist Idlib group is attacking both the friendly pro-Turkish militias that protect Idlib, and the hostile Russian and Syrian troops.

Despite a cease-fire agreement, Russian and regime forces occasionally exchange fire with Idlib rebels and pro-Turkish Syrian militia. However, a major al-Assad ground offensive against the province is not likely because neither Russia nor Turkey is interested in a confrontation. Mr. al-Assad and the Russians would like to gain definitive control of the territory, but this would inevitably lead to a military crisis with Ankara, atrocities and a new wave of refugees flooding into Turkey – something that both the European Union and the Erdogan regime would do much to avoid. Still, to Mr. al-Assad Idlib is a profound affront. When Islamists’ attacks wear down Russian patience, he will strike.

In northern Idlib and along the border with Turkey, we find the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), a coalition of armed Syrian anti-Assad opposition groups. They number around 25,000 fighters. One of their missions is to secure strategic positions in the region, thus serving as a tripwire to prevent a regime onslaught on the Sunni rebel enclave. The SNA’s main purpose, though, is to help Turkey maintain and extend its security zone inside Syria.

Kurdish territory

Further east along the frontier with Turkey, Ankara’s militias are facing Kurdish forces in coalition with Arab tribes, which number between 40,000 and 45,000. Supported by a very small American force of 500 to 600 troops, and monitored by the Russian military police, they still control the largest part of the border. Both the U.S. and Russia are trying to prevent further Turkish-Kurdish confrontations. The preferred Russian solution would be a Kurdish deal with the al-Assad government. For the Turks, this means their security belt along the border may never be completed.

Kurdish control extends further east and south. The Kurds control a vast area, north and east of the Euphrates River all the way to the Iraqi border.

Facts & figures

The al-Assad regime controls the area south and west of the Euphrates, but it also has very small enclaves in Kurdish areas. To prevent a major outbreak between Turks and Kurds, or Kurdish and al-Assad troops, Russian military police are monitoring sensitive border areas. Russian and American forces there are meant to prevent Turkish expansion. At the same time, Russians are also limiting the transfer of military assistance from the Syrian Kurds to the Turkish Kurds. President al-Assad is convinced that Turkey will never withdraw from any part of Syria that it occupies. And indeed, in the areas controlled by Turkey, the Turkish lira is used, Turkish is taught as a second language and large Turkish investments are funding infrastructure.

On one hand, limited pro-Russian Kurdish autonomous presence in Syria would give the Kremlin more influence over both Ankara and President al-Assad. On the other, Moscow’s commitment to the Damascus regime (though not necessarily to its president) is ironclad. Russia would therefore not mourn a complete Kurdish surrender to the forces allied with Mr. al-Assad.

In the adjacent northeast and some areas further south, including the main oil-producing regions, a different conflict is unfolding. The Kurdish forces there, with some American support on the ground and in the air, are confronting regime forces, pro-Iranian militias, and a resurgent Islamic State. Both for the regime and for the Iranians, the road under their control along the western bank of the river is the only military and logistical land route connecting Iran to Syria and Lebanon through Iraq available to them.

The Syrian Kurds are good fighters but poor administrators of this mixed Arab-Kurdish territory. They have resources, mainly oil revenues, but they are not making good use of them. Instead of offering better salaries, they are forcing conscription. Likewise, they are not sufficiently attuned to Arab complaints about the poor living conditions in the area. This is breeding resentment, which Mr. al-Assad is trying to exploit.

The U.S. is trying to arrange a Kurdish-Turkish political understanding to keep the Russians at bay, but the chances of success are very slim. If the Biden administration withdraws American troops, the Russians will become the sole arbiters between Turkey, the Kurds and the al-Assad regime.

Sidelines

In the southwest, Moscow has not lived up to its pledge to Israel that it would keep Iran and its proxies at least 80 kilometers from the Israeli Golan Heights. As a result, Israeli forces are attacking Iranian and pro-Iranian troops almost daily.

All statistics on the Syrian economy after 2012 are educated guesses.

Yet another confrontation is taking place in the south. Pro-Iranian militias and the regime’s 4th Armoured Division, led by a younger brother of Mr. al-Assad, are competing for control against the regime’s Fifth Army, a Division force, which is led by Syrian officers loyal to the Russians. Each is recruiting former rebels to local militia forces. Anti-government activities there are still haunting the regime forces.

Finally, in the eastern desert along the Iraqi border, Islamic State is rising from its ashes.

Economic hardship

All statistics on the Syrian economy after 2012 are educated guesses. It is believed that by 2021 over 80 percent of all Syrians living inside Syria fall below the poverty threshold. Just before the outbreak of the civil war, the Syrian economy had been hard-hit by a few years of drought. President al-Assad’s discriminatory water policies and tough response to peaceful protests triggered the first revolt in Daraa in March 2011. The regime’s atrocities triggered widespread armed opposition and international economic sanctions, restricting trade with most countries.

Additional restrictions came into force in June 2020 under the U.S. Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act. The legislation forbids business connections with the regime’s economic enablers, a very wide definition. The gesture scared foreign investors. The banking disaster in Lebanon also froze the accounts of many Syrian entrepreneurs.

The World Bank estimates that by 2018, about a third of Syria’s housing and half of its health and education facilities had been destroyed. The war damage is estimated at around $300 billion, four times the country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP). Rebuilding will take at least a decade.

In 2010, the GDP per capita was low, $2,380; by 2019, it had halved. Inflation is high. Between January 2011 and January 2021, the black-market Syrian lira deteriorated from 50 to at least 3,500 lira per $1. In 2020, the country’s central bank first issued a 5,000 lira note and the government reduced food and petrol subsidies while also imposing strict rationing. Purchasing power has eroded steeply. By 2020, a general in the military was earning $50 a month, and a soldier less than half that sum. This is breeding deep resentment, public protests, endemic corruption and crime – even in the military where, until 2011, it was rare. By late 2020 and early 2021 bread and fuel were in short supply and there were long queues even in Damascus and the Alawite region, leading to sporadic protests.

The most important component of any postwar reconstruction is the return of displaced persons, but under the present regime, refugees fear retribution. The various international sanctions deter foreign investment in regime-held territories. President al-Assad’s cronies take their cut out of incoming international aid. And the Gulf states are reluctant to invest because of the Iranian presence.

Foreign companies cannot operate in Syria without partnering with the ruling elite or their agents, and the top tiers of the security apparatus run cartels and rackets. The judiciary and regulatory bodies are rigged. Furthermore, regime-held territories are only symbolically united. New warlords have emerged, and pro-Assad and pro-Iranian militia and local army commanders are oppressing the local Sunni population.

Scenarios

Even though Syria is still recognized by the international community, and Syrian borders appear on every map, the country as it was in March 2011 no longer exists. What is left is a half-empty vessel without much of what defines a state.

The al-Assad regime has no control over some 35-40 percent of the territory of the country and 60 percent of its people, who are either living in rebel-held areas or abroad. Insurgents are attacking in the south and Islamic State is regrouping in the east. Ethnoreligious groups and foreign powers are tearing the land apart. And yet, the fact that central, western and southern Syria are still under one titular authority means the state is still hanging on.

For as long as the al-Assad regime endures, Syria is likely to remain in limbo. While the Russian-Turkish equilibrium continues, Idlib will stay under rebel control. As long as the American support for the Kurds continues, the same applies to regime-Kurdish-Turkish tensions in the north, and regime-Kurdish tensions in the east.

It is likely that roughly a third of the northern border area will de facto become a part of Turkey. The coast will be ruled jointly by Damascus and Moscow. In the northeast and further south, east of the Euphrates, the Kurds and their Arab partners may eventually gain some autonomy, but only if the Biden administration does not forsake them. A Kurdish autonomous area would free the U.S. from its obligations in that region, but it would also serve Russian interests, as it would allow Moscow to keep a Kurdish sword of Damocles over both Turkey and the Assad regime. Still, the Russians would accept an alternative reality in which Turkey and the Assad regime devour the Kurdish zone.

For Iran, while Iraq serves as a cash cow, Syria is an expensive project. Some oil revenues from the east and from commercial assets are dwarfed by the huge investment required to maintain the Iranian military presence and civilian entrenchment. But Syria, as the gateway to Lebanon, Hezbollah and the Mediterranean, is crucial to Iran’s long-term strategy. Iran has been establishing shrines and religious Shia universities there, which serve as recruitment and conversion centers, as well as high schools. It is building large neighborhoods designed for families of Shia militiamen and other loyalists in Damascus and other major cities. This Iranian colonization is unpopular with the Assad regime and the Russians, but they are unable to stop it. Albeit incrementally, the demography of Syria is changing.

The Syrian Golan will be a precious strategic bridgehead when Iran and Israel engage directly in battle. Iran cannot evacuate southern Syria and Israel cannot accept its presence there. The south will therefore remain hostage to the simmering Iranian-Israeli confrontation.

Russia will not be leaving Syria in the foreseeable future. Its presence on the Syrian coast appears permanent, and its influence in Damascus irreversible. The Soviet Union considered Syria, rather than Egypt or Iraq, its most precious strategic asset. Russian President Vladimir Putin reinstated this policy in 2015, and there are no signs that this will change.

Finally, the prospect for democratization under the present regime is dim. On January 25, a United Nations committee discussed how to rewrite Syria’s constitution and electoral law ahead of the 2021 presidential elections. However, Mr. al-Assad is unwilling to accept these changes, as well as UN monitoring of the elections. And he would probably be reluctant to agree even to a very limited Russian democratization initiative.

But no regime is eternal. Due to the destruction of the civil war and the worsening socioeconomic conditions, President al-Assad and his Alawite ruling elite are vulnerable. Unlike his father, the leader failed to create a stable bond with other religious denominations, especially Sunni Arabs. The Alawite elite is still paramount, but without alliances, this may prove ephemeral.

Secular Sunni Arabs, Christians and the Druzes are the Alawites’ natural allies. The Kurds can accept Damascus authority, but Kurdish-Arab stability would cost the central government some Kurdish autonomy. A new, less coercive regime under joint Alawite-Sunni rule is possible. This would suit Moscow, and be more acceptable to the Biden administration. With a tacit U.S.-Russia understanding, Turkey would be unable to prevent such an outcome. Depending on the security situation, the new regime could either ask Iran to stay or leave. Still, only massive concerted pressure from Moscow, Washington and Damascus would dislodge Iran. Israel’s approach would depend on this new government’s relations with Tehran and Hezbollah.