The future of public debt

With the Covid-19 crisis pushing public debt to record heights in many countries, it is worth wondering how they will pay it back in future. Several solutions have been proposed, but all carry severe flaws. In some cases, they are even legally dubious.

In a nutshell

- Paying for huge public debt will be a herculean task

- Some governments are considering exceptional solutions

- Canceling or inflating away the debt present difficult dilemmas

Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, many countries have seen their public debt rise to record highs. As hopes for a rapid end to the health crisis and a quick economic rebound begin to fade, these states face questions not only about how to pay back that debt, but whether they should pay it back at all. Many prominent economists have begun advocating writing off this debt, while others say it could be rolled over to future generations.

To pay or not to pay

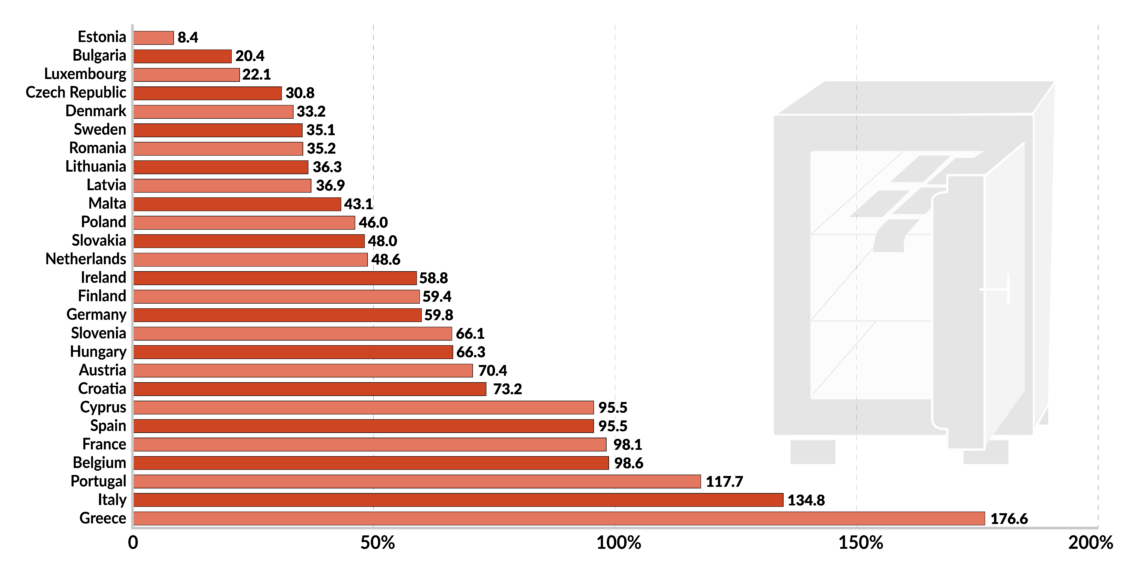

Some rich, fiscally responsible eurozone countries will have no trouble paying back the debt they have incurred fighting the Covid-19 crisis. Estonia and Luxembourg, for example, entered the pandemic with debt levels equal to 8.1 percent and 21.3 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) respectively. For Luxembourg, some forecasts put the ratio at 30 percent in the aftermath of the crisis, a level perfectly sustainable for an AAA-rated country.

The fiscal situation is far more difficult in other European Union member states, some of which happen to be the worst-hit by the coronavirus. Italy, for instance, could see its public debt balloon to almost 160 percent of GDP this year, while its economy could shrink by 10 percent. Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to rise to nearly 200 percent, Spain to some 116 percent and France to nearly 117 percent.

Such large debts cannot be paid back without a major fiscal adjustment.

Theoretically, such large debts cannot be paid back without a major fiscal adjustment. For the moment, most experts agree that austerity would be the worst way to deal with the problem. The disastrous consequences of the austerity measures imposed on Greece during its sovereign debt crisis still weigh on European policymakers’ minds.

Free lunch

“Spend as much as you can, but keep the receipts” is the new edict of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for governments. Only 10 years ago the IMF – as a member of the European troika, alongside the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission (EC) – bailed out eurozone countries on the brink of default and forced them to implement extremely harsh austerity programs.

Today, the EC is on the same spendthrift wavelength as the IMF and the ECB. In late March, the EU suspended the Stability and Growth Pact – a set of fiscal rules designed to prevent member states from spending beyond their means. According to the agreement, member states’ budget deficits should not exceed 3 percent of GDP, while their national debts should not surpass 60 percent of GDP. The crisis is turning out to be the “Keynesian moment par excellence,” just as French-American Nobel Prize-winning economist Esther Duflo predicted in March of this year.

Facts & figures

Steep decline, slow recovery

For all the debt accumulated during the crisis to be sustainable, what countries desperately need is strong, long-term growth.

Yet, the enormous economic fallout following the lockdowns worldwide implies negative growth rates: -13 percent for the eurozone in the second quarter of 2020, and -8.7 percent over the entire year, according to the ECB. Growth could recover some of its lost ground by the end of the year and reach 5.2 percent in 2021, only to slow to 3.3 percent in 2022.

These forecasts are optimistic and rely on assumptions that the recovery will be “V-shaped” – a quick return to growth after a steep decline. Whether that occurs depends on how rapidly demand comes back and how quickly scientists develop an effective treatment or vaccine for Covid-19. The recession could last longer, however, and take on a U shape (a long period between decline and recovery), a W shape (a quick recovery and second decline) or an L shape (multiple shutdowns over a period of years, with sluggish growth or stagnation).

In a recent speech, ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos insisted that the speed and scale of the recovery are “extremely uncertain.” There is no guarantee, he argued, that the expected growth will suffice to reduce the debt that remains after the crisis recedes. In fact, most European countries will wind down their shock-absorbing fiscal policies very slowly, leading to large deficits for years.

The upcoming recession will bring unseen levels of unemployment and myriad business failures, with entire sectors shrinking or disappearing. For governments, this will entail high fiscal and social costs, as well as a substantial erosion of their tax base. They will struggle to balance the need to boost growth and keep public debt in check.

Genie out of the bottle

In the absence of growth, governments could use inflation to alleviate their debt burdens. Inflating away debts was quite common until the late 1970s. Some say it should make a comeback in the post-Covid world, as it would help governments reduce the real value of their debts.

One could see the ECB’s recent extraordinary balance sheet enlargement as a move in that direction. In early June, the bank increased its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) by 600 billion euros to a total of 1.35 trillion euros and extended the program’s duration to June 2021. Also, the maturing principal payments from securities purchased under PEPP will be reinvested until at least the end of 2022.

At the same time, net purchases under the ECB’s asset purchase program (APP), reactivated in September 2019 by then-President Mario Draghi, will continue at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros. These will be made alongside purchases from an additional 120 billion-euro “temporary” program, running until the end of the year. Moreover, when securities purchased under APP mature, the ECB will reinvest the principal payments for an indeterminate period.

The exceptional liquidity that central banks provided has not yet produced inflation.

That enormous rate of money creation could soon lead to inflation, even high inflation. Some economists already fearfully anticipate post-pandemic inflation rates close to double digits in the United States. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet grew from $4.29 trillion to $7.09 trillion between early March and mid-June. It is expected to reach $10 trillion by the end of 2020.

Against the odds, the exceptional liquidity that central banks have provided has not produced inflation so far, in the U.S. or in Europe. On the contrary, eurozone headline inflation has fallen sharply – to 0.1 percent in May and 0.3 percent in June this year. Commodity prices are falling; oil prices have collapsed and consumers are reluctant to get out of their lockdown cocoons. Bond yields indicate that investors do not anticipate inflation either.

There is no simple explanation as to why inflation has not surged. One reason may be that all the liquidity pumped into the economy finally did not lead, as was initially expected, to global demand that exceeded the drastically reduced supply.

Deflation, rather than inflation, is therefore the threat that will likely preoccupy the ECB in the coming months. The main problem with deflation is that it increases debt in real terms. That genie might soon be leaving the bottle.

Financial repression

After the 2008 crash, a team of IMF economists recommended a steady dosage of financial repression (among others, through caps on interest rates) as the best means for liquidating public debt.

Financial repression, taken broadly, is any measure that a government uses to channel private-sector money to itself. Typically, it implies that interest rates on savers’ deposits are lower than the rate of inflation. This insidious form of saver expropriation (tantamount to a tax on saving) helped governments manage the enormous sovereign debts they accumulated during the global financial crisis.

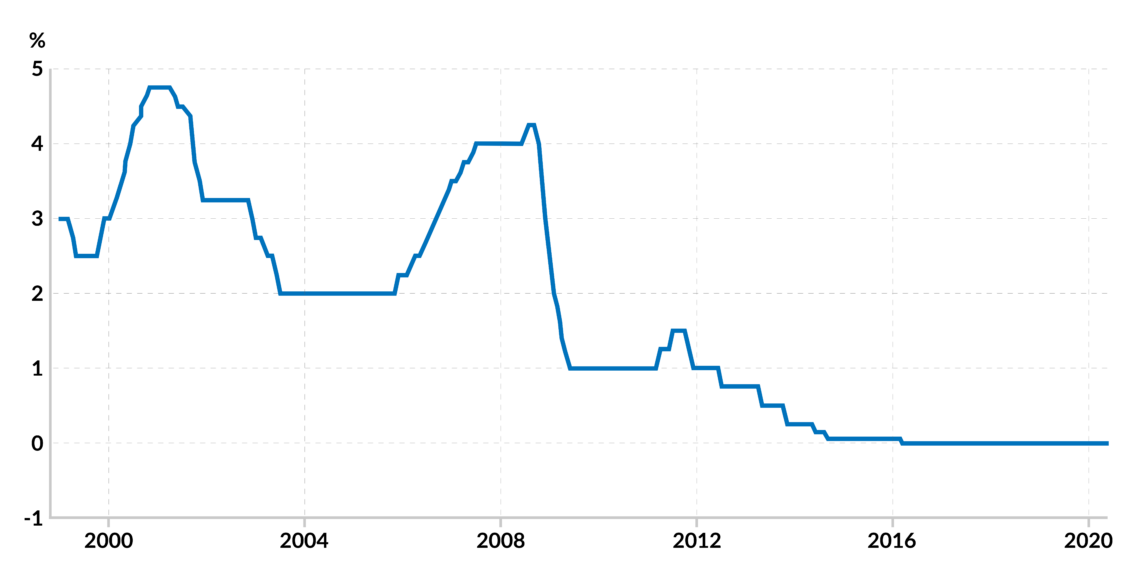

The problem is that for a decade inflation has been declining. So have deposit rates, stuck at near zero. The ECB’s actual key policy rate is slightly negative (-0.5 percent). There is hardly any space left for financial repression.

Facts & figures

A further cut in the ECB’s main policy rate seems unlikely, as it would hurt the profitability of European banks, many of which have not fully recovered from the 2008 crisis. “Deep” negative rates would encourage saver flight into cash and nonfinancial assets. Also, if rates were pushed too low, they could become counterproductive for accommodative monetary policy. Economists have studied this phenomenon, pointing out that quantitative easing could reach a point where it becomes contractionary. If this were to happen, it would be catastrophic under current conditions.

Currently, the ECB is paying banks to lend. Its targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) now offer participating banks a rate as low as -1 percent, to encourage them to lend as much as possible to distressed households and firms.

Cutting rates is not off the table though. “We are ready to adjust them if necessary, as is true for all our instruments,” ECB chief economist Philip Lane said in a recent interview.

A more radical option to reduce the debt burden, briefly mentioned by former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, is “expropriation.” He does not specify whether this means introducing a wealth tax, as advocated by other French economists like Ms. Duflo, Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez.

Canceling debt

Another scenario currently under discussion in academic and policy circles is the cancellation or restructuring of public debt. A group of French economists suggests that the ECB should simply write off the trillions of euros in sovereign debt it purchased under APP and PEPP. There would be no negative economic consequences since, they claim, the debt burden is transferred to no one. The only loser, if there was one, would be the ECB. A central bank, even if it suffered a major capital loss, cannot go bankrupt, the argument goes. As the ECB stated itself some years ago, “central banks are protected from insolvency due to their ability to create money and can therefore operate with negative equity.”

Canceling the Covid-19 crisis debt is not an option for the ECB. That would be illegal.

However, canceling the Covid-19 crisis debt is not an option for the ECB. First, it would be illegal. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits monetizing debt. If the ECB buys sovereign bonds and does not later seek repayment, this constitutes illegal “monetary financing,” ECB executive board member Fabio Panetta has said.

Second, citizens might lose trust in the EU’s common currency if the ECB decided to follow such a course. Canceling public debt could trigger fear of financial chaos. The ECB is unwilling to choose this path, not least because it would be dangerous on inflationary grounds.

Helicopter money

Some economists contemplate more subtle versions of debt cancellation. One proposal is to convert all EU member state debt into “zero-interest perpetual bonds.” This way, debts would never be repaid, nor would interest be paid on them, and governments could continue spending with impunity.

Another option to finance coronavirus budget deficits, advocated among others by economists at the Centre for European Policy Studies, is “helicopter money.” The ECB should provide distressed firms and households with cash via national government budgets (or even the EU budget, as former Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker suggests).

The idea is to spare countries from having to issue new debt. Debt-to-GDP ratios would not be altered in this scenario. EU lawyers would, however, need to find creative arguments around the legal interdiction to monetize debt.

Scenarios

The intergenerational transfer of debt is the most likely scenario for the ECB. Here the idea is that debt is simply “rolled over” to future generations. For such a Ponzi scheme to work, interest rates must remain exceptionally low for a long time, while growth rates recover substantially. In any case, the latter must exceed interest rates. Otherwise, future generations’ welfare would be compromised.

If growth rates were lower than interest rates (which could happen if the recession were to become long and severe), government debt would increase faster than the economy. The public debt would grow so large that governments would be unable to find buyers for all of it, forcing either default or substantial tax increases.

The question is whether debt rollover is not another hidden form of debt monetization. The advocates for all these solutions argue that while we should not panic, there is reason to worry. It seems even they realize that debt sustainability should indeed not be taken lightly. In the end, austerity might be waiting around the corner after all.