Focus Germany: Balancing the Energiewende

The government of Germany is determined to implement its energy transition goals, which are much more stringent than those set by the EU. An increase in renewable energy sources will mitigate reliance on foreign energy imports, but Berlin will have to strike a difficult balance between cleaner energy and economic growth.

In a nutshell

- Germany is investing generously in its long-term strategy for transitioning to sustainable energy sources

- So far little progress has been made, and coal remains the largest contributor to electricity in the country

- If the German government does not adjust its goals to market realities, it risks another failure

Germany is determined to take the global fight against climate change seriously. Since the beginning of this century, the world’s fourth-largest economy and its sixth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2) has announced ambitious steps to reduce its carbon footprint and speed its energy transition toward a greener, cleaner future. However, its first official strategy (referred to as the “Energiewende” or, loosely translated, energy transformation) was criticized for falling short of its targets despite calling for a rapid expansion of renewable energy.

Recently, Germany announced another major round of even more ambitious measures to close past loopholes and overcome shortcomings. It is unclear whether the latest plan will face the same fate or stand better chances. The main lesson to be drawn from the German experience is that the green energy transition is about balancing economic priorities and climate urgencies, even in a country as rich and dedicated as Germany.

Facts & figures

Energy in Germany

- Germany is the sixth-largest emitter of CO2 in the world, accounting for about 2% of total carbon emissions after China (27.8%), the U.S. (15.2%), India (7.3%), Russia (4.6%), and Japan (3.4%)

- Germany is the seventh-largest primary energy consumer in the world at 2% of global consumption, after China (24%), the U.S. (17%), India (6%), Russia (5%), Japan (3%) and Canada (3%)

- The German economy is the fourth largest in the world at US$4 trillion (nominally). It accounts for 4.7% of the global gross domestic product after the U.S., China, and Japan (IMF, 2019)

- Within the EU, Germany is both the largest primary energy consumer at 19.2% of the total, and the largest economy at 21.3% of the total GDP at current prices (BP, 2019; IMF, 2019)

- Following the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear accident in March 2011, Germany decided to phase out nuclear power by 2022, starting with the immediate closure of the eight oldest plants

- At 46%, renewables are now the largest indigenous source of energy in Germany, having surpassing coal at 38% in 2018

- One in five cars in the international production line is German made

Energiewende

In September 2010, the Federal Government of Germany adopted its first official environmental targets for 2050. “Energiewende” became the nickname for the country’s overarching, long-term strategy to transition to a sustainable green energy system. Importantly, “green” in this context stands for far more than the decarbonization agreed upon in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

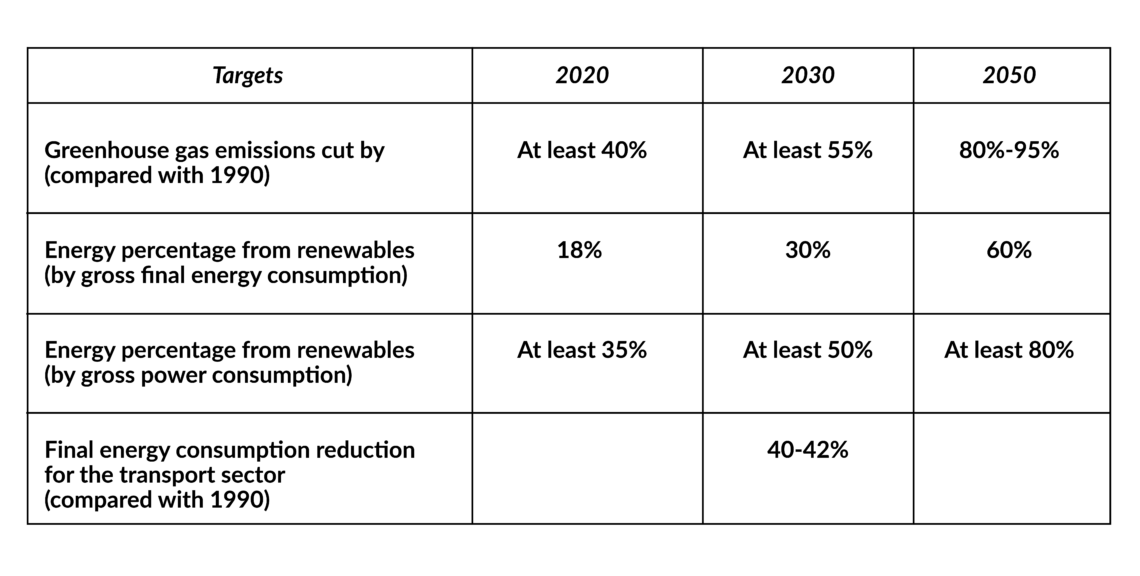

In Germany, the main objectives include: phasing out nuclear energy by 2022; using a minimum of 60 percent of final energy consumption and 80 percent of gross electricity production from renewable energy – thus crowding out fossil fuels, particularly coal; reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80 to 95 percent by 2050; and doubling energy efficiency. While all this will have the beneficial side effect of improving energy security by reducing import dependence, it is also meant to be achieved while sustaining industrial competitiveness and growth. These targets are much more ambitious than those set by the European Union.

Facts & figures

Germany's climate and energy targets

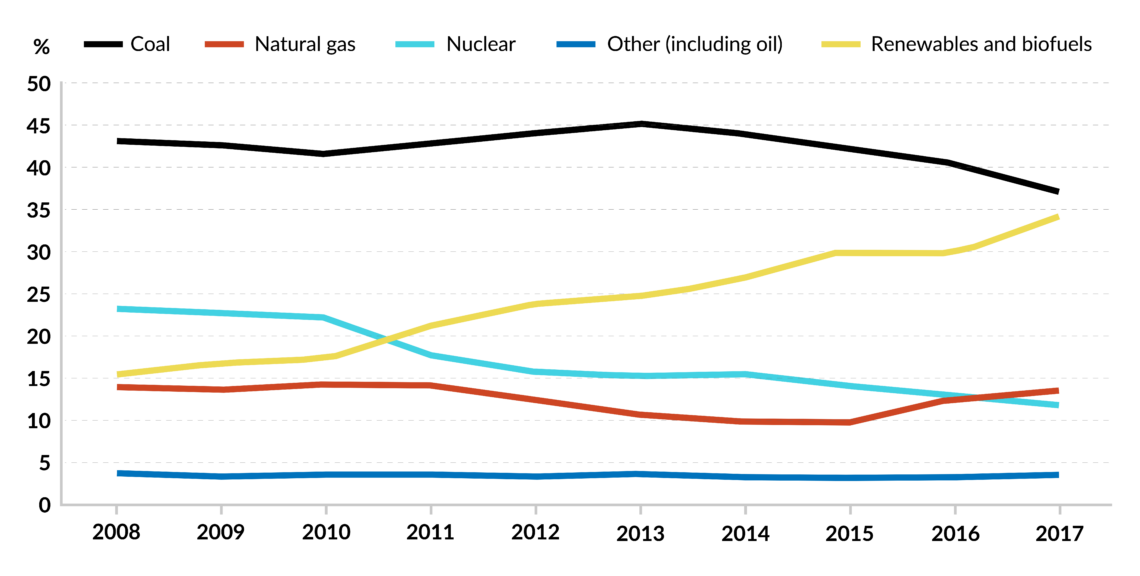

Driven by generous subsidies, the growth in renewable energy has been remarkable, particularly in the power sector, where green energy has more than made up for the decline in nuclear power. Between 2010 and 2016, renewables increased by 87,200 gigawatt-hours (GWh), while nuclear generation declined by 55,700 thousand GWh. Such a change is perhaps Energiewende’s main and, in the eyes of many, only success. The rest remains a work in progress.

Setbacks

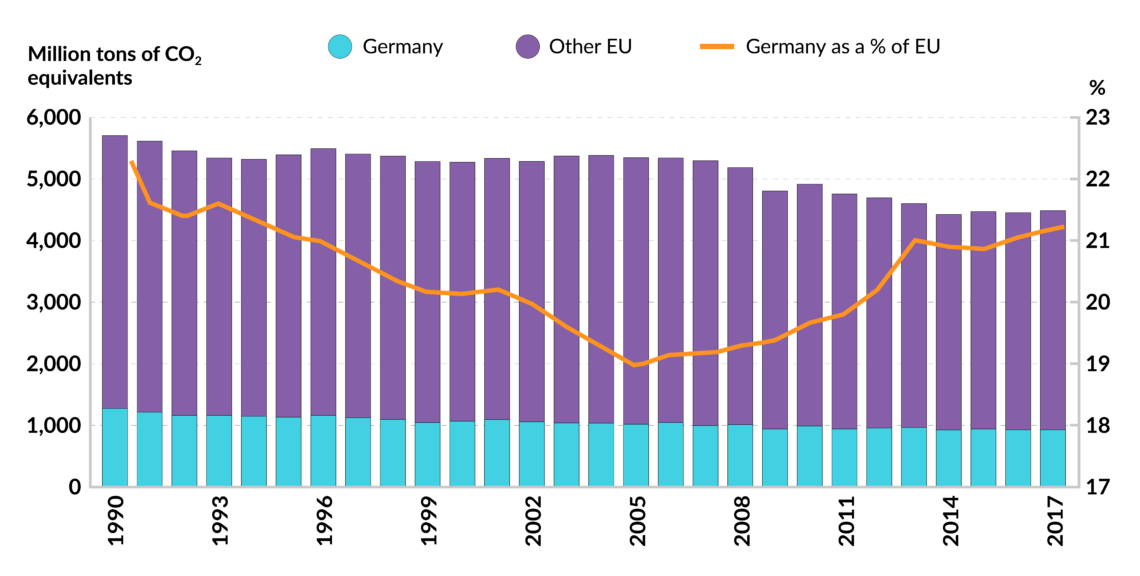

The major failure of the Energiewende is in carbon emission reduction. Despite the notable expansion in renewable energy, Germany’s carbon emissions have hardly declined, forcing the government to scrap its 2020 climate targets.

Emissions in the transport sector are almost exactly where they were for the past three decades, and in June 2018 the government conceded that the 2020 reduction target would only be reached in 2030 at the current rate. Germany also hoped to have one million electric and hybrid vehicles on the road by 2022; by 2018 there were only 44,419 electric vehicles and 236,710 hybrids, despite generous government support.

In June 2018 the German government conceded that the 2020 reduction target would only be reached in 2030

Some blame poor progress in the transport sector on Germany’s powerful car industry. Germany is Europe’s largest automotive market in production and sales, and the world’s largest car exporter, with automotive exports accounting for more than 16 percent of all German exports in 2017 – the product group with the largest export share.

However, a more important factor can explain why, despite its aggressive efforts and relative success in expanding renewable energy, Germany has failed to achieve meaningful progress in limiting GHG emissions: as far as CO2 emissions are concerned, the Energiewende has replaced green with green, namely, nuclear power with renewable energy.

Facts & figures

Germany's CO2 emissions, 1990-2017

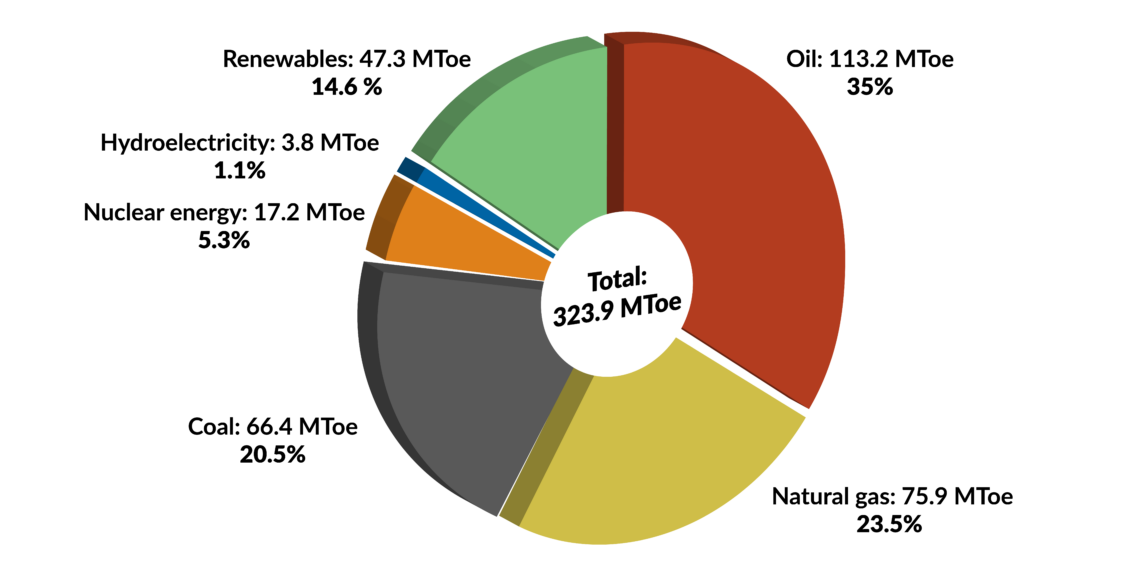

Aware of this failing, Germany has recently committed to phasing coal out by 2038. Use of the latter has been in decline, but remains the largest source of power generation in the country. More than half of Germany’s total power generation capacity and nearly 80 percent of its primary energy mix are from fossil fuels, largely imported from Russia.

Facts & figures

Germany's primary energy mix in millions of tons of oil equivalent (MToe), 2018

Another attempt

In 2019, Chancellor Angela Merkel formed a ‘climate cabinet’ composed of all relevant ministries. As a result, in September 2019, Germany announced a second, tougher round of measures to put Energiewende back on track, through the country’s first Climate Action Law and the Climate Action Programme, which is a detailed set of measures to reach the 2030 climate targets in all sectors of the economy.

The government has now not only committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 – an even more ambitious target than what was initially set out in the Energiewende – but has also made the commitment legally binding. According to the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, Germany is the first country to set legally binding limits on how much CO2 each sector can emit every year. If a sector deviates from the reduction path, the responsible ministry will be required to take immediate corrective action. As put by Minister of the Environment Svenja Schulze, “From now on, all of the ministries will be climate-action ministries.”

Germany is the first country to set legally binding limits on how much CO2 each sector can emit.

It is unclear, however, whether the monitoring system will be effective and whether ministries can correct a deviation from targets without causing too much economic dislocation. Besides, who is going to enforce punishment if the government fails? And who will be punished? Consequences are unlikely to be significant.

Price tag

To improve the chances of success of the new plan, Germany announced a 54 billion euro spending package to support various industries, especially the transport sector. Electric vehicles are receiving a significant boost as the government aims to register 7-10 million electric vehicles by 2030. Rail travel will also benefit from tax reductions at the expense of air travel, with plane tickets taxed more heavily.

The federal government is also introducing carbon pricing – a measure often seen as crucial to encourage the shift away from carbon-intensive industries to greener options. The carbon price will apply to previously shielded sectors, primarily transport and building insulation, but it is unclear what the price should be in order to be effective. The German government opted for a fixed price per ton of CO2 initially set at 10 euros, rising to 20 euros in 2022, 25 euros in 2023, 30 euros in 2024, and 35 euros in 2025. Later on, it will be set by the market within a fixed band, according to the German authorities.

The measure sparked significant criticism among climate advocates and angered protestors who argued that the prices set are too low. Some called for a price of at least 40 euros to start with, while others such as the German Mechanical Engineering Industry Association (VDMA) recommended CO2 pricing as high as 110 euros per ton. Furthermore, it is ambiguous whether the carbon prices set are in nominal terms, with inflation factored in, or not. Ms. Merkel, however, defended the price level, arguing that only a gradual increase would be socially acceptable. “We have to bring the people along with us,” the chancellor said.

Advocates have also called for increased spending on green causes, but the government remains committed to a balanced budget overall – the so-called “black zero.” In other words, funding to tackle climate change needs to come from higher taxation, or from expenditure cuts elsewhere in the state budget.

The energy transition is a noble cause, but it does not come cheap in a world built on fossil fuels.

Still, it is difficult to provide accurate estimates about the total price tag of the energy transition. When asked to provide such a figure for the Energiewende, the German government said that assessing the full price entails more than measuring the support cost of renewable energy, which accounted for roughly 19 billion euros yearly.

A study by Clean Energy Wire contrasts the significantly diverging estimates. On one hand, it describes the statement of former Green Party environment minister Jurgen Trittin, who said in 2004 that the burden placed on households by the renewable energy surcharge would amount to “only around one euro per month, the price of a scoop of ice cream,” as an easy target for ridicule. On the other, the current Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, Peter Altmaier, stated in 2013, when he was the environment minister, that “the costs of the Energiewende and of the transformation of our energy supply could add up to around one trillion euros by the end of the 2030s” without policies in place to lower the costs.

The energy transition is a noble cause, but it doesn’t come cheap in a world built on fossil fuels. There are reasons why even high-income countries like Germany find it almost impossible to deliver on such bold commitments; and most of their policies would be infeasible in less wealthy nations.

Even Germany is at risk of overpromising, especially when climate measures weaken some of its core energy-intensive industries. In the United States, President Donald Trump’s administration has clearly stated it was not going to take such a risk. For Germany and other countries in a similar situation, achieving the energy transition requires a balance between meeting the economic needs of today and safeguarding the climate of tomorrow.

It is going to be impossible for Germany to reach its ambitious climate targets without either storing renewable energy (a technology yet to be fully proven), taking baseload from its neighbors; or switching to natural gas – which will mean falling short of its GHG targets and increasing dependency on Russia. A degree of realism is urgently needed. The energy transition is going to be about balancing the energy mix gradually, with green sources replacing fossil fuels in countries that are built on the latter. Other countries that are only beginning to build their energy sector might well be able to leapfrog fossil fuels by creating a new system from scratch.