Germany’s Zeitenwende still has a long way to go

An economic downturn could threaten support for reducing a trifecta of dependencies: energy imports from Russia, exports to China and the United States for security.

In a nutshell

- Germany faces difficulties undoing the mistakes of the Merkel-Schroeder eras

- Defense spending, despite increases, remains short of NATO’s 2 percent goal

- Higher energy prices may weaken the public’s willingness to support Ukraine

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s speech in the Bundestag on February 27, 2022, was a watershed event in German history.

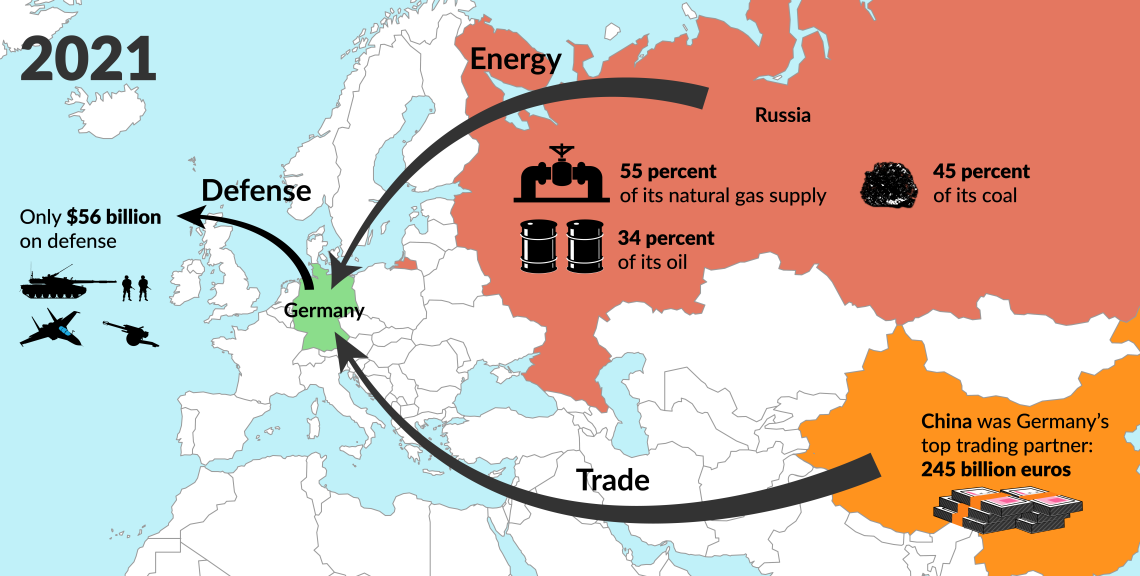

Mr. Scholz spoke of a “turning point” – Zeitenwende in German – triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “The world after that is no longer the same as the world before,” the German leader said. The statement gave the impression that Germany had suddenly become aware of its responsibilities. From now on, the nation of 83 million people, with Europe’s largest economy, would no longer entrust its security to the United States alone, its energy supply to Russia and its economic growth to exports to China.

This turnaround is primarily about German-Russian relations, the need to strengthen defense capability and deterrence, and secure energy supplies. Mr. Scholz announced he would provide the Bundeswehr with a credit-financed special fund of 100 billion euros. That is a significant amount, but to meet the expectation that NATO members invest at least 2 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) in defense, an additional 25 billion euros would have to be spent annually, adjusted for inflation.

Major overhaul needed

The change required is enormous. In 1989, Germany invested 2.7 percent of its gross domestic product in national security, and by 2014, it was only 1.1 percent. Only since 2017 has the share risen again – in 2021, it was 1.5 percent. However, 41 percent of this was spent on personnel and pension entitlements. In France, 26.5 percent of defense funds go to equipment; in Germany, only 16.87 percent do. On the day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bundeswehr Inspector Lieutenant General Alfons Mais, the highest-ranking officer of the German Army, said that the army had been severely weakened after years of austerity and is no more up to the task.

Under Mr. Scholz’s predecessors, Gerhard Schroeder (1998-2005) and Angela Merkel (2005-2021), German foreign and security policy assumed that the nation was surrounded only by friends. This misjudgment led to a security policy recklessness that manifested itself in the neglect of the Bundeswehr. When the U.S., the United Kingdom, Poland and other NATO partners supplied Ukraine with heavy weapons, the Bundeswehr was already in such a deplorable state that it could not comply with the Ukrainian government’s requests.

However, national security is only one of the many ruins Ms. Merkel has left to the Scholz government. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s threat to cut off gas supplies would not be nearly as effective if Germany had not done everything it could to make itself economically blackmailable. Udo Di Fabio, a former judge with the Constitutional Court, delivered a devastating verdict on German energy policy:

No country with a keen sense of the mechanics of foreign power relations would have actively promoted or passively accepted such a massive energy dependence on Russia as Germany under chancellors Schroeder and Merkel. Criticism from the U.S. of projects such as Nord Stream 2 was politely forbidden, criticism from the Baltic states was not taken seriously. The Federal Republic pursued an almost romantic energy policy.

Facts & figures

Germany’s 3 major vulnerabilities

Self-inflicted wounds

Reduced Russian oil and gas supplies are hitting Germany particularly hard today because rising global demand is accompanied by a politically engineered shortage that began long before the sanctions against Russia. Germany has been suffering from the consequences of self-inflicted economic wounds that have dominated energy policy since Ms. Merkel embraced the positions of the Greens.

In 2011, she used the destruction of four reactor units in Fukushima, caused by an earthquake and a tidal wave, as a pretext to order Germany’s withdrawal from the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The nuclear and coal-fired power plants were gradually shut down, and domestic gas extraction by fracking was dispensed with, citing possible environmental damage.

Another concession with which the chancellor drew the left-wing opposition to her side was the opening of borders during the migration crisis of 2015-2016. Compared to the Greens, the party Die Linke and the left wing of the Social Democrats, she thus distinguished herself as an ally in the “fight against the right.” The informal party coalition on which the chancellor relied ranged from the left-wing fringe to the Greens to deep into the CDU, which lost its conservative and Christian-democratic brand core.

Revising wrong decisions that have accumulated over five legislative periods would overwhelm any government, even if the parties supporting it had not been involved in setting those misguided policies.

Today, German parties have to say goodbye to a series of apparent certainties that have been questioned for more than 20 years only on the fringes of the party spectrum branded as populist. To revise wrong decisions that have accumulated over five legislative periods would overwhelm any government, even if the parties supporting it had not been involved in setting those misguided policies.

The three parties in the Scholz government had helped shape Germany during these two decades. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Greens governed under Mr. Schroeder of the SPD from 1998 to 2005. Twice, from 2005 to 2009 and 2013 to 2021, the SPD belonged to a grand coalition with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) under Ms. Merkel. The Free Democratic Party (FDP) had been Ms. Merkel’s junior partner in the black-yellow coalition from 2009 to 2013. All three parties of the “traffic light” coalition and the CDU, as the largest opposition party, played a part in the drama that turned the economically strong and politically self-confident Germany of Helmut Kohl (who served from 1982-1998) into a less reliable and crisis-prone partner for the Western world.

The conditions supporting the German export industry have deteriorated significantly following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war.

Rectifying misguided policies

The responsibility for the mistakes and omissions of the Merkel era lies first and foremost with the CDU. Friedrich Merz, who emerged from the turmoil as Ms. Merkel’s successor as the new CDU chairman, had been the chancellor’s most prominent opponent within the party for years. So, it was not too difficult for him to support the turnaround that Mr. Scholz announced in the Bundestag. To prevent conflicts in the party, however, he has so far avoided criticizing the former chancellor, who had shaped the profile of the CDU and still enjoys significant support in it. To stand openly against them would be understood as a concession by the new CDU chairman to the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the only party in the Bundestag to have opposed them on almost all issues.

Ms. Merkel’s popularity was evident in a poll conducted three weeks before the federal election in September 2021. In it, 80 percent of those surveyed approved of her job. That judgment reflects the economic upswing experienced by Germany during her chancellorship.

Robust German growth had been the result of an exceptionally favorable combination of several factors, led by cheap energy from Russia. But other factors contributed to the boom times: an upswing in the global economy, particularly from rising demand in China, the wage restraint of German workers and the weak external value of the euro. The higher tax revenues financed the expansion of the welfare state, the energy transition and a climate policy that was executed without regard for the industry’s concerns.

Meanwhile, the conditions supporting the German export industry have deteriorated significantly following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war. The International Monetary Fund revised downward its growth forecasts for 2022 and 2023. In May 2022, it estimated Germany’s 2022 growth at around 2 percent; by July, the projection was only 1.2 percent. Numerous small and medium-sized enterprises, especially in the tourism and gastronomy sectors, have had to close due to the Covid lockdowns. It is feared that many companies will not survive the increased energy prices and the reduction of gas supplies in autumn and winter.

To relieve consumers, the government has thus far made 30 billion euros available. On September 4, the German chancellor announced an additional 65 billion-euro relief package, with Mr. Scholz finally acknowledging the obvious: “Russia is no longer a reliable supplier of energy.” It represents a sharp departure from the failed strategy of “change through trade.”

The situation has kept changing dramatically. On September 5, the German government even agreed to continue operating until April 2023 two of the remaining three nuclear power plants that had been scheduled to close at the end of the year. Also on that day, the Kremlin said it is stopping gas supplies to Europe through Nord Stream until Western sanctions are lifted against Russia.

See also

Germany’s high-risk energy strategy

Will support for sanctions hold?

Nevertheless, the party Die Linke and the AfD are planning a “hot autumn” for the government. There were violent protests when Chancellor Scholz wanted to explain the federal government’s plans at a citizens’ meeting in Neuruppin on August 18. Unlike Ms. Merkel, who largely eluded debate, Mr. Scholz strives to establish contact with the citizens. However, he lacks charisma, and he keeps as many options open as possible in his statements. The chancellor is wary of the tense relations in the coalition with the Greens and the FDP and tries not to provoke the left in his own party, whose influence has increased after the Bundestag election.

Meanwhile, the approval ratings of the traffic light coalition are falling. In a survey at the beginning of August 2022, only 14 percent of respondents said they were “very satisfied” with the government’s work, while 37 percent said they were “very dissatisfied.” Satisfaction with the chancellor has also slumped. Recent polls also show his SPD party losing popularity as the Greens gain.

Opposition to supporting Ukraine is particularly strong in the SPD. Not only Mr. Schroeder but Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and numerous other Social Democrats are known for their pro-Russian stance, which was not questioned in the party until after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. If the energy crisis in winter leads to mass social protests, the pressure on the government to lift or at least mitigate the sanctions against Russia is likely to increase, as demanded by Die Linke and the AfD.

In the CDU, too, more voices want to force a change of course. The spokesman of this current movement is Saxon Prime Minister Michael Kretschmer, who is pushing for quick negotiations to “freeze” the war because sufficient Russian gas flows in the coming years are essential to keep social peace in Germany. There has been a debate even in the FDP since Wolfgang Kubicki, vice president of the Bundestag, proposed activating the Nord Stream 2 pipeline as soon as possible. The FDP chairman Christian Lindner and numerous other politicians of the party have spoken out vehemently against it.

Only the Greens have thus far resisted the temptation to question the turnaround in Russia policy announced by Mr. Scholz in the Bundestag. Among the German parties, only they had spoken out against Nord Stream 2 from the outset. In the German Bundestag, the Greens campaigned even more than the CDU and FDP to support Ukraine against Russia with the supply of heavy weapons.

Scenarios

The future development of German policies will largely depend on how German society will react to the consequences of the failed energy policy and the resulting dependence on Russia. There is a high probability that fewer Germans will be willing to bear the costs of supporting Ukraine, although polls currently show still strong public backing for standing up to Moscow. Demonstrations against the government could bring even more people to the streets yet this year than the previous demonstrations against the tough measures to fight Covid. The pressure on the government to reverse the “turning point” announced by the German chancellor will increase. Whether the coalition will stand up to it depends above all on whether the left in the SPD is loyal to its chancellor or will join the protests.