Germany’s high-risk energy strategy

The Merkel government hopes to overcome the shortcomings of Germany’s energy transition plan with new initiatives such as a coal phaseout by 2038, a new climate policy package and an ambitious hydrogen strategy. But the blueprint still lacks coherence and cost efficiency.

In a nutshell

- Germany’s energy transition plan is not cost-efficient

- Full implementation could cost up to 5 trillion euros

- The plan’s objectives are unlikely to be reached

Launched in 2011, Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition) was created without any cost analysis or consultation with the European Commission and neighboring countries. As a result, the strategy is being carried out through trial and error. So far, it has cost more than 300 billion euros, but results have been negligible.

Germany sees itself as a global leader in energy transition, with the Energiewende a blueprint for other countries to follow. But the European Commission and many European Union member states have criticized Berlin’s unilateral energy policies, as well as its lack of cooperation and coordination. Other European countries perceive the German model as inefficient, too expensive and potentially harmful to several industries.

The German automobile industry was ahead of the curve for decades, but it has now fallen behind Tesla and its Asian rivals, which had invested much more in electro-mobility and hydrogen prior to the diesel scandal. The latter has further weakened its international reputation. The sector has also been affected by incoherent energy policies.

In the next decade, some 100,000 automotive jobs (approximately 12 percent of the present 830,000) are at stake. An additional 100,000 jobs in other European countries could also be lost, disrupting supply chains. Despite generous government support, the original plan to have one million electric cars on Germany’s streets by 2020 proved unrealistic. Although sales of electric cars increased in the first half of 2020 due to generous new state subsidies, around 80 percent of all cars sold still have a combustion engine. As long as the range of battery-powered cars and the availability of recharging stations are not significantly improved, most customers will not switch to electric cars.

As an industrial country, Germany’s energy transition is the only one in the world that is presently phasing out nuclear power and coal simultaneously.

Highlighting the gap between its declarations and its policies, Germany submitted its mandatory National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) to the European Commission at the beginning of June, five months after deadline – the last EU member state to do so, other than Ireland.

Current challenges

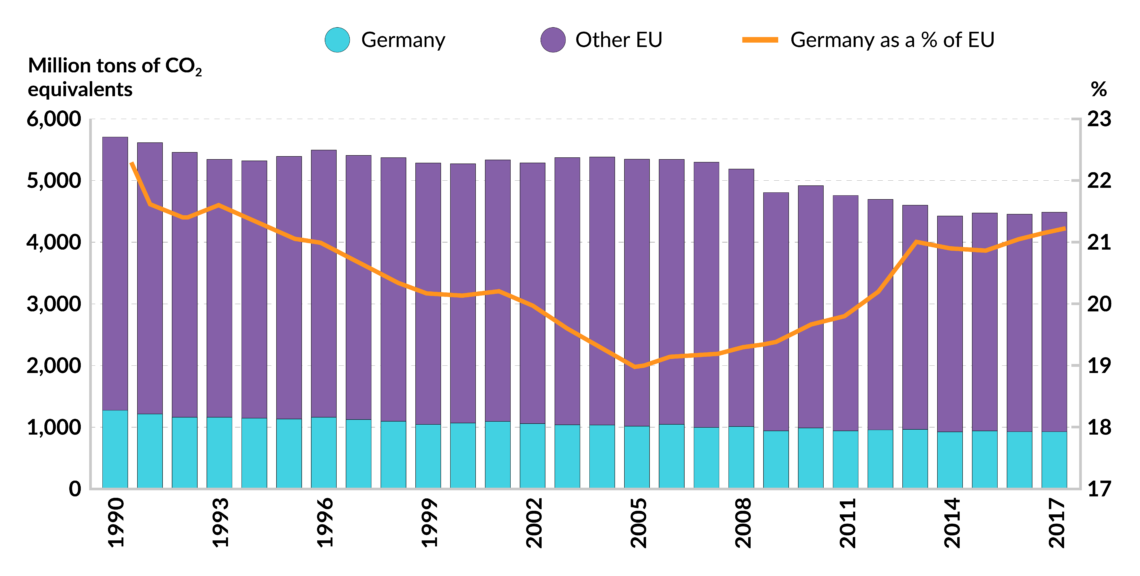

As an industrial country, Germany’s energy transition is the only one in the world that is presently phasing out nuclear power and coal simultaneously. As the fourth-largest economy and the seventh-largest primary energy consumer, Germany produces the sixth-most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the world, even though it accounts for only 2.1 percent of global emissions. The new climate protection plan envisages a 55 percent decrease by 2030 and a 95 percent decrease by 2050.

An overview of the current state of the Energiewende’s implementation:

- GHG emission reduction. In 2019, Germany’s annual emission reduction improved by almost 5 percent compared to 2018 (30.8 percent), and 35.7 lower than 1990 levels. This was largely due to a decline in coal use as a result of higher carbon prices for the Emissions Trading System (ETS) allowances.

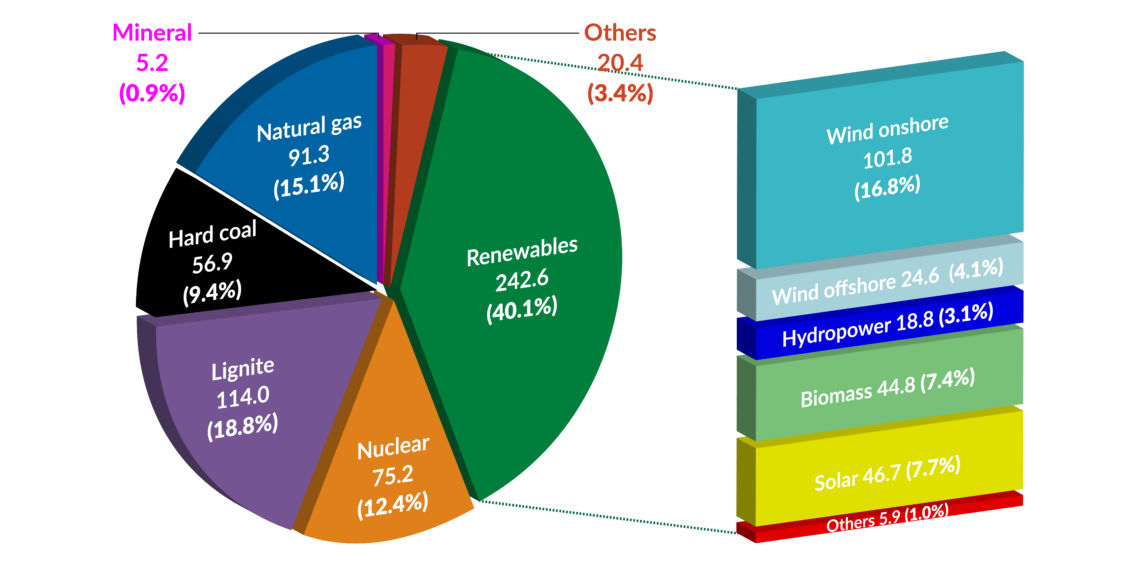

- Rising import demand. At the moment, Germany can only cover 28 percent of its domestic energy needs, or half of the 1990 figure.

- Share of renewables (RES). In 2019, Germany’s share of RES in its electricity mix went up to 43 percent. Berlin intends to reach 65 percent by 2030. But the present share of RES represents only 17.5 percent of total primary energy consumption, which would need to be raised to 30 percent to accomplish this. Despite the impressive increase in the share of intermittent RES, over 95 percent of electricity demand still needs to be covered by conventional power plants in the absence of sun or wind to guarantee baseload and electricity supply security.

- Need for new gas power plants. Due to the coal phaseout, the German government plans to build two new gas power plants to replace the shortfall of regulated energy for intermittent RES.

- New climate policy package. The German government agreed on another 54-billion-euro climate package for companies and households designed to ensure that Germany meets its 2030 carbon reduction targets. At its core was a rise in CO2 pricing in the mobility and heating sectors. As of 2021, a CO2 charge of 10 euros per ton will be applied, set to rise to 35 euros per ton by 2025.

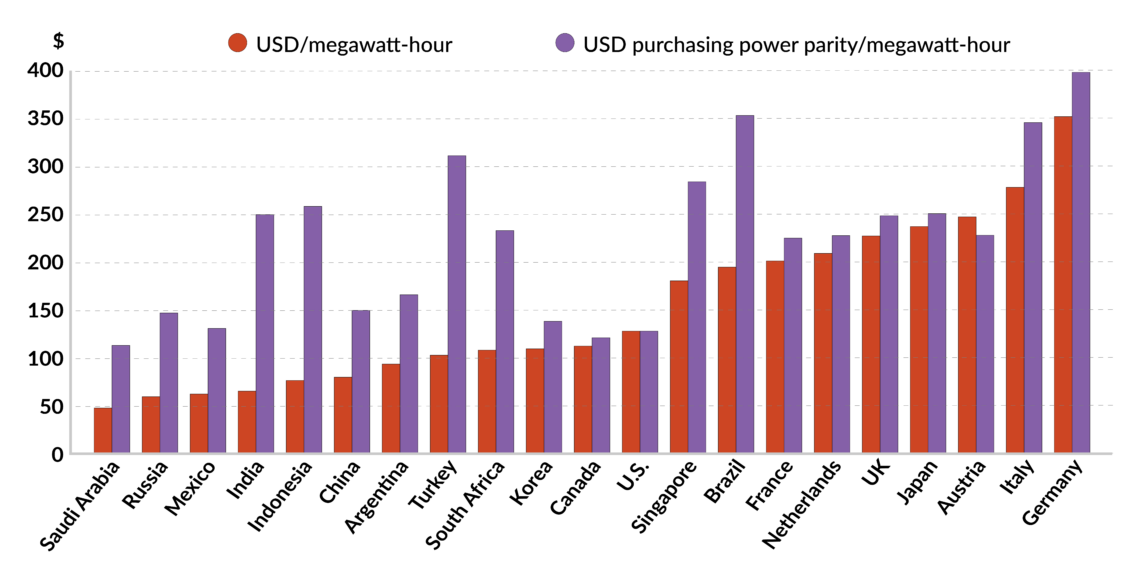

- High electricity prices. Since 2000, Germany’s electricity prices have risen by 116 percent, from 13.94 to 30.43 cents per kilowatt hour (KWh) in 2019. The price increase is not a result of demand and market developments, but rather a consequence of government interference with taxes, charges and levies, which have almost tripled since 2000 (from 5.9 to 16 cents/KWh).

Since January 2020, new measures have been agreed, such as lifting the solar cap and a new minimum distance between windmills. An ambitious hydrogen strategy was also adopted, as the only realistic decarbonization option for energy-intensive industries.

Facts & figures

Impossible goals

It is perhaps unlikely that these targets will be achieved. The expansion of wind power on land lacks local acceptance, and has stagnated in recent years. The adopted measures in the transport and building sectors are not sufficient. To reach the 65 percent target for the share of RES in the electricity mix by 2030, Germany would need to build an additional 4 gigawatts of onshore wind capacity every year, which appears rather unrealistic despite recent reforms of distance requirements. Berlin is facing widespread “not in my backyard” attitudes.

Germany is still a net exporter of electricity, with some 60 terawatt-hours. With the simultaneous nuclear and coal exit strategies, it might become a net importer. But Berlin has overlooked that its neighbors are also reducing their electricity supply capacity in the coming years and decades.

The Energiewende’s lack of cost-efficiency could prove even more expensive with the recent coal phaseout (which has a heavy price tag of more than 50 billion euros), a 54 billion euro climate policy package as well as further unspecified investment and subsidy costs. Altogether, this might add another 150 billion euros to the 300 billion already spent, with annual subsidies of 20 to 25 billion euros. The cost of the long-term energy transition strategy could reach 4.6-5 trillion euros by 2050.

Germany will receive the second-largest share of the EU’s Just Transition Fund.

In 2018, the German government decided to establish the Commission for Growth, Structural Change and Employment to develop a realistic coal phaseout strategy, taking into account the social, economic and regional impacts of the closure of lignite and hard coal power plants. Approximately, 18,000 jobs will directly be affected, and an additional 10,000 indirectly.

If the coal phaseout is to be completed at the latest by 2038, the planned deadlines will be reviewed in 2022, 2026 and 2029 by taking into account energy supply security, electricity prices and climate protection. The package includes a law for the restructuring of coal regions and an agreement with operators of lignite power plants with fixed exit dates for individual power plants. In return, operators will receive compensation payments totaling 4.35 billion euros despite NGO campaigns against payments to energy companies and operators. In their view, compensation is not needed as the EU’s rising CO2 prices will make coal power plants unprofitable. But the government feared courts might rule in favor of compensation.

The restructuring of the German coal regions and financial support for social adaptation measures will cost another 40 billion euros. For its coal phaseout, Germany will receive the second-largest share (876.6 million euros, after Poland) of the EU’s Just Transition Fund.

Germany’s coal phaseout includes a higher maximum price for auctions to end the operation of hard coal power plants by 2026. This may lead to the earlier closure of newer and cleaner plants, while dirtier and older lignite coal facilities will operate until 2038. This contrasts with the recommendations of the Coal Commission and has been heavily criticized by some of its members. It could cause additional emissions of 40 million tons of Co2 by 2030.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Even if all the recently agreed energy and climate policy initiatives were to be fully implemented, they would probably fall short of achieving the Energiewende’s targets.

While Germany and the EU will certainly improve on their new ambitious hydrogen strategies in the next decades, they tend to overlook that hydrogen is not a silver-bullet solution to all energy problems. Large-scale commercialization is unlikely to take place before 2030. Overall, the new German and EU energy and climate targets for 2030 demand huge subsidies as well as public and private investments at a time when the economy is severely weakened by the pandemic.

The German coal phaseout is in line with the EU’s policies for decarbonizing its energy system. But while Germany is subsidizing its national coal phaseout with more than 50 billion euros for around 18,000 jobs, the Polish coal phaseout will affect more than 100,000 workers who will not receive the same support as their German counterparts. Even a Europe-wide coal phaseout by 2030 would not be enough to achieve the EU’s newly agreed target to decrease its emissions by 55 percent (it was previously 40 percent) if no other decarbonization efforts are initiated.

Neither Germany nor the EU will single-handedly solve the climate issue. The present EU28 share of global emissions is 9-10 percent and will further decline to just 5 percent by 2030. But the 50 percent decline of the EU’s share of global emissions will primarily result from a significant rise of emissions from China, India, Southeast Asia and Africa, not from the ambitious EU and German climate policy.

The overlooked assumption that other countries and regions will follow suit has already proven unrealistic and naive. Germany and the EU’s climate policies are disconnected from those of other major emitters, and they have only led to free riding at the expense of a more effective global climate change policy.