The specter of degrowth

Economic growth has been the engine of our civilization and, lately, a source of environmental angst. However, turning it off is not the solution.

In a nutshell

- Returning to the pre-growth economic era is not a feasible proposition

- Growth has also caused challenges, environmental change chief among them

- Decoupling growth from pollution and resource depletion is possible

Concern over the environment, especially climate change, has popularized the idea of degrowth, an opposition to sustainable growth. The notion is not without very serious problems, however.

Many tend to romanticize the bygone era before economies’ accelerated expansion while, at the same time, taking many growth benefits for granted. The assumption is that humankind was once free from materialistic concerns. Also, it was supposedly less individualistic and more connected with nature – unlike in modern society. To some extent, those who believe this may be right. In the not-so-distant past, members of our species did not have the time and opportunity to think in materialistic terms. They were too busy constantly worrying about food and survival.

Growth ethics

More than three millennia ago, possibly the most powerful person on earth, the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun, died at 19, likely from an infection following a broken bone. Fast-forward to the late 17th century: the most powerful woman on earth, Queen Anne of Great Britain, had 17 pregnancies and passed away in what today we consider middle age. Her longest-living child, William, died at 11.

These two examples remind us that in the past, even the most prominent individuals were plagued by great misery defined by scarcity – of adequate healthcare. For the common lot, the scarcity regarded food, shelter, heating and other fundamental basics.

Growth has been the ‘great escape’ from misery.

Economic development, based on growth, has been an organized (albeit largely decentralized) struggle against staggering levels of scarcity.

Many people also see poverty as an issue to be dealt with (which it is), supposing wealth is natural and poverty artificial. However, it is the other way around: poverty is the natural state of man. It takes effort, through production and exchange, and value creation – in other words, economic growth – to exit humankind’s natural condition of poverty and misery.

By taking wealth as natural or granted, this vision leads to the assumption that the solution to poverty is redistribution from the wealthy. In fact, however, it takes growth to reduce human poverty – hence its ethical dimension. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Angus Deaton put it, growth has been the “great escape” from misery.

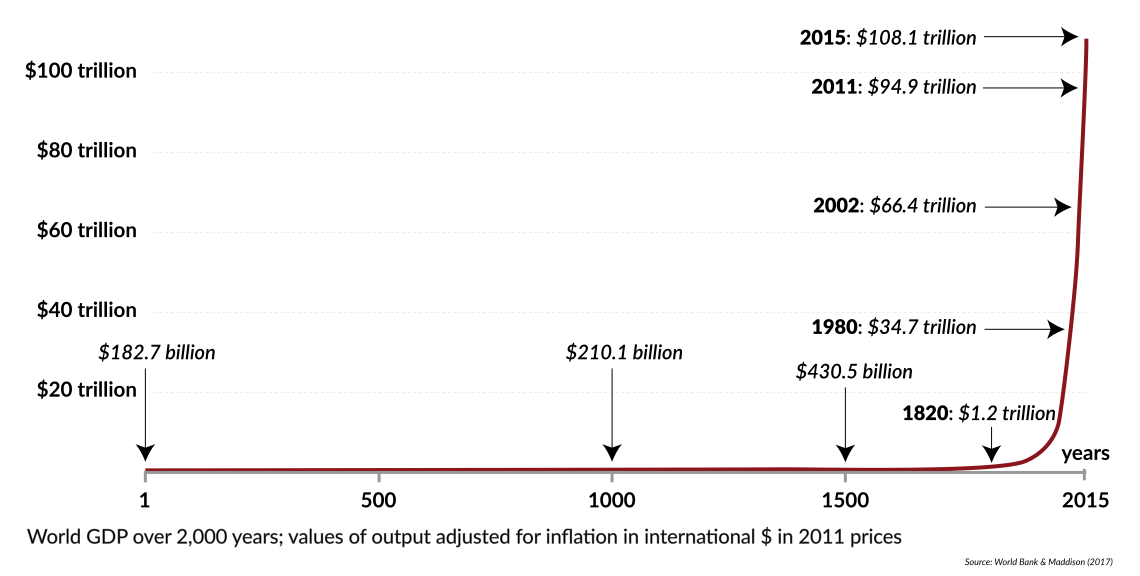

The wonders of growth

Institutional progress toward economic (for entrepreneurship) and scientific freedom (for innovation) has enabled modern growth. This phenomenon, based on a change in ideology toward freedom and markets, has been called “the great fact” by the economist Deirdre McCloskey. Thanks to the pioneering work of economic statistician Angus Maddison, we know that the trend for gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in rich countries has the shape of a hockey stick curve on a graph. Even the commercial revolution in the Middle Ages (The 12th Century Renaissance) and the Italy-born Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries did not bring an incredible increase in GDP per capita. That began to happen in the early 19th century, thanks to industrial revolutions.

Facts & figures

Economic growth was almost nil for 1,500 years

Two centuries later, this “great enrichment” is measured by a factor of around 16. Living standards have reached previously unimaginable levels – buoyed by extended life expectancy, dramatic reduction in child mortality, increased health standards, reduced working hours, improved housing, increased consumption and countless other gains.

What economic growth enables us to access today is even more remarkable because of new products. Two technologies have reduced the effort required to produce what we need: human exchange and specialization according to comparative advantage on one hand; and specialized mechanization (thanks to energy and technical innovations) on the other. The number of hours an average person living in rich countries must work to put food on the table has shrunk to minimal levels.

Facts & figures

Factbox: The Rule of 72

Behind the seeming miracle of improving living standards lie slight percentage increments in economic growth rates. “The rule of 72,” tells us roughly how many years it takes to double a country’s GDP given its expansion speed: one can find it out by dividing 72 by the annual growth rate. So, a 1 percent growth rate implies 72 years to double the GDP; for a 6 percent growth, it is only about 12 years.

In discussing poverty reduction and enabling a population to pull themselves out of misery, such down-to-earth, materialistic calculations matter greatly: global absolute poverty rates fell from roughly 80 percent to 10 percent in the last two centuries.

Employment and public spending

Not only does economic growth improve standards of living, it also enables unemployment reduction. Admittedly, the “creative destruction” process generates unemployment simultaneously as it creates jobs, but Okun’s law describes how economic growth leads to an overall increase in employment.

Inequality also falls with higher per capita GDP after a certain threshold

Growth also enables the financing of increased public spending (infrastructure, public services) even if the latter rises faster than GDP per capita (Wagner’s law). Typically, inequality also falls with higher per capita GDP after a certain threshold (before which inequality logically increases, given that only some sections of the nation are jumping early on the bandwagon of development), as described by the Kuznets curve.

Path to degrowth

Economic growth is not without issues. Production and consumption can generate “negative externalities,” including waste and emissions harming health or the environment. It also leads to the rapid depletion of many natural resources, from fish to sand. These real drawbacks have created doubts about GDP growth: not only have other indicators than GDP been developed to better measure progress, but growth itself is being questioned, even vilified.

Pessimists about growth go back to British economist Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), who worried that the population would grow faster than resources, leading to a world of scarcity and famines. The idea was recycled by the American biologist Paul R. Ehrlich in the late 1960s in his book “The Population Bomb” – quickly followed by the Club of Rome’s report on “The Limits to Growth.” The authors envisioned and condemned materialistic consumerism fed by and feeding economic growth.

In the late 1970s, the philosopher Hans Jonas coined the concept of “imperative of responsibility,” the idea that influenced the later “precautionary principle” (included, for example, in the constitution of France in 2005). The principle boils down to the recommendation that scientific research and innovations deemed risky to the environment and humankind ought to be severely restricted.

Read more on growth:

Low productivity puts Western economies at a crossroads

Fake problems, real dangers

Promethean growth (based on scientific progress and innovation) has become a great fear. A zero-risk approach was promoted as a solution. In 1987, the Brundtland Report coined the notion of sustainable development: while economic development was necessary, its authors reasoned, it had to be reconciled with societal and environmental imperatives.

In the early 2000s, the concept of decroissance (degrowth) finally emerged in France, gaining traction along with climate concerns. Severe temperature conditions in the northern hemisphere in the summers of 2021 and 2022 have helped popularize the notion in the post-Covid/Great Reset era. Based on the various Malthusian intellectual influences mentioned above, degrowth is about reducing GDP to protect the ecosystem and ensure it remains livable for humans. According to this idea, degrowth should start in rich countries to give poorer countries some breathing space to develop before they arrest their growth as well.

Hard and soft versions

A radical version of degrowth flourishes in movements such as Extinction Rebellion, which places the Earth and animals above humans, who are sometimes described as parasites. For example, Finnish “deep ecologist” Pentti Linkola (1932-2020) advocated radical depopulation schemes and giving up procreation.

Innovation and entrepreneurship can generate cleaner ways to produce and consume.

A soft version of degrowth is that of “organized sobriety” promoted by media-hyped French engineer Jean-Marc Jancovici. He opposes both “efficiency” (the current economic model) and “unplanned” degrowth that would bring poverty. “Sobriety” means using less energy (de facto impacting GDP growth), less international trade, less consumption of meat, restrictions on the use of plastics and localism in production. Mr. Jancovici’s project is more radical than sustainable development, which still promotes “green” growth. To reduce CO2 emissions, the Frenchman champions nuclear power.

Defending growth

Optimists about growth, so-called cornucopians, defend it against Malthusian worries. In 1980, the economist Julian Simon famously challenged Professor Ehrlich in a wager about the evolution of the prices of different metals over the next decade. Increased scarcity, predicted by Mr. Ehrlich, should translate into price increases. In 1990, Mr. Simon won the bet, as prices had fallen. The winner’s reasoning was that prices serve as powerful incentives to economize on natural resources. Pricing of pollution also incentivizes us to pollute less.

A related notion posits that property rights give us incentives to be good stewards of natural resources. The absence of property rights (a “communism of resources”) leads to the widely described “tragedy of the commons,” as each user wants to acquire as much of the resources as possible before others do the same – eventually leading to its exhaustion. Institutional reform toward conservationism can help solve ecological issues. Admittedly, the effort is much more complex for global public goods and requires diplomatic coordination.

On such a basis, innovation and entrepreneurship can generate cleaner ways to produce and consume, decoupling GDP growth from polluting emissions, for instance. Of course, one must be wary of the danger of greenwashing and the risk of outsourcing polluting production processes (such as with so-called green electric cars). However, cleaning up production processes is a valuable trend, even if the progress is not as fast as we would like to see. Innovations have enabled humans to produce much more food off the same land surface (Norman Borlaug’s green revolution).

Thanks to the degrowth idea, environmental awareness and conservationism have fostered ethics of consumption that are probably helpful. Together, better consumer education, ecological awareness, more societal involvement (genuine solidarity), and pollution pricing can promote sustainable development based on “greener” growth.

Degrowth now

Degrowth rejects the green growth and sustainable development approach. At the same time, the potential road to degrowth, even the soft version, does not promise to be easy. And there are sobering precedents of what may be in store if degrowth became state policy.

Rationing schemes and tight regulations would inevitably lead to central planning and its traditional cohort of inconsistencies. No wonder degrowth also promotes socialism in a new guise of “participatory socialism.” However, in such a world, the power could easily go to those who talk louder while participation would be selectively channeled, as consistently evidenced by history.

Many radical degrowthers hold no brief for democracy, giving preference to technocracy (Jancovici) or dictatorship (Linkola). The flip side of such advocated measures as watching everyone’s energy consumption or carbon footprint is an encroachment on privacy and individual freedoms. There are fears that the rationing could involve an energy or CO2 pass and that new, smart electric meters would affect widespread surveillance.

Facts & figures

Degrowth’s socialism

In a finite world, degrowth proponents see infinite growth as impossible. Humankind must close the extractivist, productivist and consumerist “cosmology” of capitalism and radically move toward an “economy of well-being,” they proclaim. Working time would be reduced, advertisement and profit banned, and social justice promoted with radical inheritance taxation, for instance. Companies would change into production cooperatives with democratic governance and be required to prove their social usefulness.

Degrowth activists promote democratic decision-making in society through citizens’ conventions. Like for the string of 19th century French socialists from Fourier to Saint-Simon, though, the role of engineers in such systems is central – democratic governance becomes very much technocratic. Citizens’ propositions would need to respect the engineers’ plan. Such a society would face knowledge and incentives problems typical of socialist systems.

Inequality would rise between those who can afford energy and those who do not – especially depending on where they live. The vast system of taxation and subsidies accompanying degrowth policies would give rise to massive regulatory and redistribution operations, overseen by bureaucracy. This modus operandi is known to lead to inertia and inefficiencies. Also, witch hunts against “unnecessary” activities (like innovation and experiments) would crimp innovation and new income generation needed to fund the “necessary” ones (like medicine) and the costly, complex redistribution system (which is taken for granted).

The green-inspired policies have undermined one critical condition for growth – energy availability.

With the rise of unaccountable, bureaucratic power, cronyism – and thus corruption – would inevitably increase in this context of scarcity. The spreading of the fear and guilt mentality would profoundly affect society, crushing entrepreneurial spirit, and negatively impacting the cultural framework for progress, taking all of us backward. And without the pull of richer people or countries, the poor would simply be hurt.

Social backlash

While many city dwellers in affluent countries, especially Generation Z, sympathize with degrowth, they are utterly dependent on growth. Eighty percent of the now city dweller population in OECD countries is sustained by a complex, modern, industrial economic system. What are these people to do? Much of the secondary and tertiary sector would now be “unnecessary.” Which urban garden will they grow?

The Yellow Vest movement in France’s big cities and their peripheries began precisely as a response to increased taxation on gas – meant to incentivize CO2 reduction. It is hard to imagine how degrowth policies will be accepted socially.

The green-inspired policies have undermined one critical condition for growth – energy availability. Disinvestment in traditional fossil energies has taken place, reinforced by the ideas of stakeholder capitalism and the Great Reset. The war in Ukraine has only increased existing trends concerning energy supply, especially in Europe, where disinvestment also concerns nuclear energy.

To some extent, degrowth is now becoming an almost self-fulfilling prophecy. French President Emmanuel Macron recently warned of “the end of abundance.” The current energy and inflation crisis puts degrowth to a new test.

Scenarios

Possible ways forward

The non-pricing of too many negative externalities (airplane kerosene, intercity highways, commuting in cars to big city centers) has prevented precise economic calculation of social costs imposed on society by various actors. There has been no proper internalization of social cost in private cost, as economist Ronald Coase would explain. Non-pricing and weakened property rights protection have thus not fostered innovation to limit the “internalized” cost of pollution or overexploitation.

Green growth, rather than degrowth, could make a difference if it is undergirded with strengthening pricing and property mechanisms. Movements like the Yellow Vests would accept such pricing as long as it is clear and accompanied by a degrowth of obese, unaccountable and costly government bureaucracies and cronyism. This sort of degrowth, materializing in lower taxes and transparency, would be the compensation for pricing externalities. In this scenario, clarifying property rights, prices and political responsibilities would be the key to cleaner growth.