Jihadists open a new front in West Africa

Countries in the Gulf of Guinea have seen an increase in terrorism activity. Lax border control allows jihadist violence to spread rapidly through preexisting criminal networks. National authorities are taking measures to counter the threat, but the issue will need to be addressed from a regional perspective.

In a nutshell

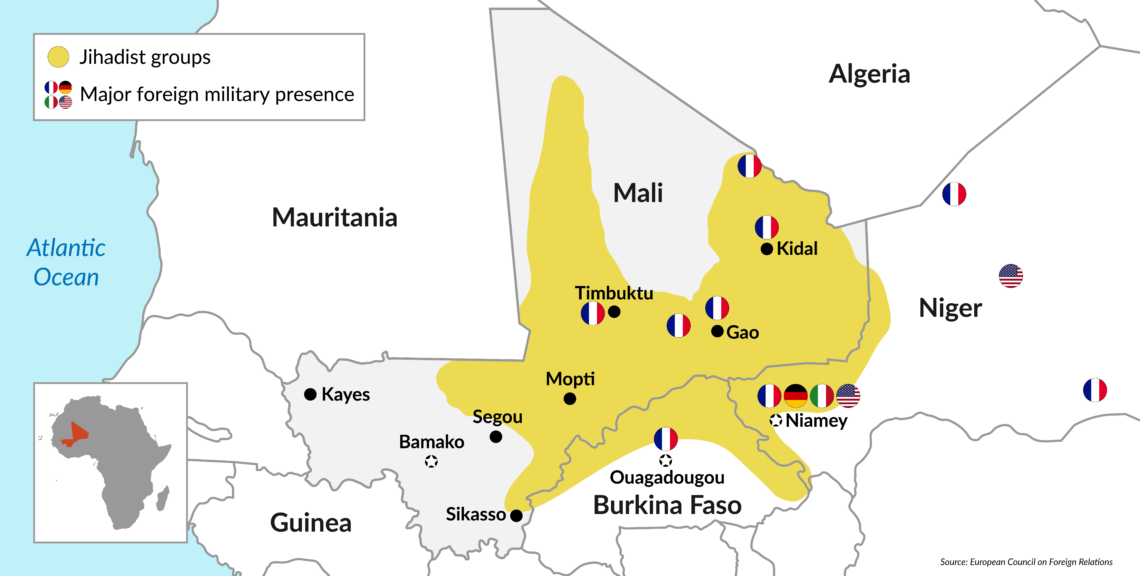

- Jihadist groups in Mali are expanding to neighboring countries

- The region is vulnerable because of ethnic and social tensions

- Rising popular discontent could aggravate the problem

On May 9, two French soldiers died in an operation to rescue two tourists kidnapped in northern Benin. The incident opened everyone’s eyes to what they did not want to see: the spread of jihadism to West Africa. Senegal, Mali, Niger, Benin, Togo, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Ghana and Cameroon are all countries that are now under threat.

First step: Burkina Faso

Originally centered in northern Mali, jihadist violence has gradually crept south to the central part of the country, which has become the main focus of attacks. The outbreaks are often the result of ethnic tensions, which have spiraled out of control. In 2017, the United Nations identified more than 1,000 incidents in the Mopti region alone. By then, the region had the highest incidence of jihadist attacks against the Malian armed forces, self-defense militias, UN peacekeeping troops (MINUSMA), rebel groups that were signatories of the 2015 peace accord, and 3,000 French regular troops involved in the “Barkhane” counterinsurgency operation.

Along with this expansion into central Mali, jihadist groups have penetrated farther south into Burkina Faso. This infiltration became so serious that on January 1, 2019, a state of emergency was declared in 14 border provinces of Mali and Niger. Jihadists had been preparing for this offensive since the early 2010s, but the first armed attacks did not begin until 2015.

There are several possible explanations for the spread of jihadism to Burkina Faso.

At first the violence was concentrated in northern Burkina Faso, with several attacks against state officials and members of civil society. In December 2016, the Ansarul Islam group was created by Ibrahim Malam Dicko. Comprised mainly of the Fulani and Rumaibe ethnic groups (the latter part of the formerly servile Tuareg population), it maintains links with other jihadist groups in Mali. In 2018, attacks increased in the north and also occurred in the western part of the country. Meanwhile, the security situation was deteriorating in the east, with about 15 attacks (involving ambushes or use of improvised explosive devices) between January and August. The most likely perpetrators were members of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Ansarul Islam, in alliance with local community leaders who studied the Quran in Mali.

There are several possible explanations for this spread of jihadist activity to Burkina Faso. Firstly, as the former Malian Tuareg rebel leader Iyad Ag Ghali said in an interview in 2017, the current, much-publicized strategy of terrorist groups is to extend the fight to new areas. While this approach may be explained by the military pressure on jihadist groups in northern Mali, where the French achieved several tactical successes in 2018 and the operational coordination mechanism was also making progress, it also shows the transnational character of jihadist ideology.

Secondly, jihadist groups were able to establish points of contact with the local population, allowing them to set up and carry out operations. Finally, the terrorist groups benefited from the disruption of Burkina Faso’s security apparatus and intelligence services after the 2014 revolution that overthrew President Blaise Compaore (1987-2014).

Spreading west

Recent attacks in the southern regions of Burkina Faso, near its borders with the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin, are evidence of a growing threat to countries in the Gulf of Guinea. This was confirmed by the arrest in December 2018 of suspected militants preparing operations targeted at three capital cities – Bamako, Ouagadougou and Abidjan – for early 2019.

Here again, however, the first signs of jihadist activity date back to the mid-2010s. Malian fighters reportedly conducted a reconnaissance operation in 2014-2015 in the W National Park, a wetlands area that straddles the borders of Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. Similarly, in 2015, several members of an active Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) cell in the Sama forest, on the border between the Ivory Coast and Mali, were arrested, though others evaded capture. Members of this unit allegedly kidnapped a Colombian nun in the Sikasso region in February 2017 before being arrested in December 2018.

Jihadist armed groups have also been recruiting in coastal countries in recent years. The Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MOJWA) enlisted members from several countries, including Guinea, Ghana and Benin. After the departure of the Nigerian Bilal Hicham from the Usman dan Fodio katiba (combat unit), a South Beninese native and Yoruban, nicknamed Abdullah, took charge of the unit. The MOJWA is not an isolated movement; according to the Libyan authorities, dozens of nationals from Ghana, Senegal and The Gambia have joined the Islamic State organization in that North African country.

The first major shock was, however, the Grand-Bassam attack in the Ivory Coast in March 2016. In that operation, allegedly directed by Malian Arab Mohamed Ould Nouini, a three-man suicide commando killed at least 16 people and wounded 33 at the Ivorian beach resort. An internal report by Ghana’s National Security Council predicted that Ghana and Togo would be the next in line. Two months later, the Beninese armed forces published a memo asking all units to “strengthen the security of the various areas threatened by terrorist attacks” and to be “more vigilant when conducting searches at the borders.”

Facts & figures

Armed groups in Mali and the Sahel

In fact, attacks increased throughout the region, particularly in Niger, where terrorist groups struck the Diffa region (in the country’s southeast) in February and again in April 2019. In May, Islamic State forces claimed to have killed no fewer than 28 government soldiers in an ambush in Niger’s Tillaberi region, near the border with Mali.

In response, there have been several measures to strengthen border security. Togo and Benin deployed additional units in the north to strengthen their territorial integrity. Joint operations were also organized. In May 2018, almost 2,000 troops and security personnel from Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Togo took part in Operation Koudalgou, which resulted in 200 arrests, including some with suspected links to jihadist groups. While such operations show that the authorities are aware of the growing threat and publicizing measures to counter it, they do raise several questions.

First, cooperation between the actors in the subregion remains difficult, even though there have been some isolated successes. One was a joint operation between Burkinabe and Malian armed forces, backed up by French technical assistance, that broke up an armed jihadist cell in Ouagadougou in May 2018. In the legal field, the West African Central Authorities and Prosecutors Against Organized Crime (WACAP) initiative, supported by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, has brought together the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and Mauritania to strengthen cooperation between courts and law enforcement in the region.

However, collaboration continues to be hampered by a culture of mistrust between and within individual states and government agencies. In addition, attempts at border control are frustrated by the population’s habit of bypassing checkpoints and the prevalence of smuggling, aggravated by the corruption of border guards and certain legal constraints. Surveillance is made even more difficult because jihadist groups tend to piggyback on the expertise and organizational infrastructure of traffickers and local criminal groups.

Socioreligious tensions

The intense migration and trade flows between the coastal states and the Sahel hinterland, along with the wide dispersion of ethnic and religious communities, encourage the diffusion of ideologies and provide easy access and ready-made footholds for jihadists. As a result, new jihadi “solidarity movements” continue to spring up and spread throughout West Africa.

Their development is encouraged by ubiquitous ethnic, political, economic and social tensions, which are another source of vulnerability in West African countries. Several common factors have contributed to the rise of violent extremism. Young people in the region are increasingly frustrated with the older generation of political leaders, who continue to monopolize political and economic power. Wide disparities remain between urban and rural areas, deepened by a high rural illiteracy rate.

The region also provides fertile ground for new religious ideologies, such as Sunni revivalism. In northern Benin, for example, there has been a wave of new mosque construction, accompanied by a more rigorous interpretation of Islamic law, including the introduction of veil wearing for women and girls. Similarly, the Ghanaian National Peace Council has had to intervene several times in response to discourage radical preaching and anti-Muslim sermons among Christian churches.

The surge of recruits to armed jihadist groups, however, cannot simply be blamed on the spread of religious ideology and funding from the Arab Gulf countries. Several studies (by the United Nations Development Programme, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, or the Institut francais des relations internationales) have shown that young people are drawn to these movements by a sense of injustice, local conflicts, and the often brutal behavior of local military and security forces. These factors have all played a significant role in the shift toward violence.

The rise of a more fundamentalist Islam provides an effective platform to win over a local audience.

The rise of a more fundamentalist Islam on the African continent does provide, for actors advocating violence in the name of religion, an effective platform to win over a local audience and gain support and funding. Local sources of anger and anti-Western sentiment then make it easier to recruit jihadist fighters.

Sunni expansionism also generates violent competition with more traditional forms of African Islam. In Guinea, for example, tensions between Wahhabi youths and Sufi scholars led to the destruction of the so-called “Tata 1” Wahhabi mosque in the Donghol district in 2014. Funded by an association in the Arab/Persian Gulf, via a Guinean association, it was taken over by a self-proclaimed Wahhabi imam.

Political blindness

These religious tensions are all the more dangerous as they occur in countries plagued by multiple ethnic, political and social conflicts, which terrorist groups know how to stir up. This applies especially to disputes between nomadic and settled populations concerning land, water, livestock and underground mineral resources. Young people are also increasingly challenging social hierarchies in regions already beset by political instability.

In Ivory Coast, attention is focused on the 2020 election. Disappointment with President Alassane Ouattara’s performance since his election in 2010 is palpable, and the integration of the rebel fighters who supported him has left its mark on the security apparatus. In Benin, political issues between the government and the opposition appear to have been largely resolved by the April 2019 parliamentary elections.

Unless urgent action is taken, the problem will only get worse.

In Cameroon, nascent independence movements in the English-speaking northwest have been prominent since 2016. Several attacks have occurred. In October 2017, separatists announced the symbolic independence of the two English-speaking regions and sparked demonstrations. The violent dispersal of these demonstrations by the security forces left at least 17 dead and helped spark a low-grade guerilla war. According to the United Nations, the conflict has claimed 1,850 lives and has forced more than 530,000 people to flee their homes over the past three years.

The most worrying aspect is perhaps the failure of West Africa’s political regimes to comprehend the multiplicity of factors that feed the jihadist hydra. Unless urgent action is taken on these ethnic, economic and sociopolitical contributors to popular discontent, the problem will only get worse.

Stopping contagion

The ethnic question is perhaps the most pressing issue. In the case of Mali, tensions between the Tuaregs, Fulani, Bambara and Dogon should not be underestimated. There can be no long-term political solution without taking into account these ethnic divisions, which can only be bridged by economic development, mutual respect, broad local autonomy and a straightforward vision of political decentralization. Faced with the inevitable friction between settled and nomadic populations, it is the job of public authorities and local chiefs to guarantee peaceful coexistence through the fair distribution of land, transhumance and grazing rights.

On the economic front, a ruthless battle against all kinds of trafficking (drugs, medicine, weapons, humans) and extortion must be waged and coordinated between the different countries in the region. These criminal activities fuel jihadism. Any progress in combating these activities will by definition weaken the terrorists. One well-known aspect of the problem, of course, is that in some countries, officials and politicians are complicit with these groups.

That puts the focus squarely on politics. Ordinary people fail to see why a jobless youth is given a five- to 10-year prison sentence for smuggling, while a minister or customs official can do the same thing on a vastly larger scale with impunity. The perception of elites being above the law and utterly corrupt are key drivers of public resentment, as they have been in places like Ukraine. International donors should use this as leverage to be much more demanding about political reform.

Finally, the problem of geographical scale should not be underestimated. The areas to be monitored and controlled are often enormous (Mali encompasses more than 1.2 million square kilometers of sparsely populated terrain), and patrolling areas of this size exceeds the resources available to local governments. Even so, border control is a priority. To bridge the gap, more cross-border cooperation, financial support from Western countries, and use of advanced technologies (sensors, satellites, drones) is essential.

This report contains information originally published by the Thomas More Institute, an independent opinion think tank based in Paris and Brussels