The last hurrah? Guyana rides the oil wave

Amid a global downturn in 2020, Guyana boasted record economic growth of over 43 percent, as it became the world’s newest oil exporter. The exploration of recent discoveries will unlock more oil riches yet for the small South American nation.

In a nutshell

- Guyana’s economy soared despite the pandemic crisis

- Oil discoveries have opened a new path to growth

- Regulatory and political challenges still loom

There is an alternative universe sitting on the northeast shoulder of South America. As the global economy shrank 3.3 percent in 2020, with nearly every country dipping into negative territory, Guyana recorded economic growth of more than 43 percent.

The force behind this result? Oil. Although the COVID-19 crisis forced many oil producers to scale down on their production, Guyana joined the club of oil exporters in 2020, shipping its high-quality crude to global markets. That came more than 70 years after the country’s earliest exploration attempts, and after the development, in record time, of its very first discovery in 2015: the ExxonMobil-operated Liza field, among the world’s biggest discoveries of the past decade.

While oil companies are still cautious about their capital spending, Guyana is expected to see a busy 2021, with companies such as American Hess allocating most of their budget for this year to the South American country thanks to attractive project economics. Guyana, the world’s newest oil-producing nation, is also expected to be among the significant contributors to non-Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil supply growth, at least for the next five years.

Guyana joined the club of oil exporters in 2020, shipping its high-quality crude to global markets.

This dramatic turn of good fortune raises several fateful questions. Will Guyana’s government maintain investment-friendly policies? Can its economy escape the resource curse that has blighted so many other developing countries? Might it be tempted to join OPEC? And how much will its oil outlook – and therefore its economic prospects – be spoiled by the climate agenda? These outcomes will have a significant impact on the country’s outlook and role in global markets.

Stabroek discovery

Guyana has been on the radar of international oil companies for decades, driven by giant discoveries in neighboring Brazil, Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago. In 2001, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) ranked the South and Central America region third globally for undiscovered oil and gas resources, behind the Middle East and the former Soviet Union. The USGS added that the potential for giant oil and gas fields was greatest in the provinces along the Atlantic margin of eastern South America, including the Guyana-Suriname basin.

But for years, companies tried to locate such resources in vain. Then in 2015, ExxonMobil hit the jackpot with the discovery of the Liza field in the Stabroek Block, which is operated by the American giant and its partners (Chinese state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and Hess with 25 percent and 30 percent shares, respectively). The discovery opened a long-awaited chapter for Guyana. One discovery after the other followed; to date, a total of 20 findings have been made, mainly in the Stabroek Block, which is 26,800 square kilometers – or roughly 12.5 percent of Guyana’s land size.

Most of these discoveries have yet to be fully appraised to confirm their volumes, but the numbers are not insignificant so far. For instance, the gross discovered recoverable resource estimate in the Stabroek Block alone is more than 9 billion barrels of oil and gas, a number that continues to be revised upward with each new discovery.

Facts & figures

It is not just the scale that is striking but also the economics. For instance, at less than $35 per barrel, the development cost of Liza is the lowest of major global offshore developments and shale plays. Once the infrastructure becomes more developed, costs are likely to come down even further. With oil prices trading at nearly double that breakeven level, the project’s returns are attractive.

Quality, too, is a draw. Guyana’s oil is light crude with low sulfur (in industry jargon “sweet”), commanding a higher price than heavier crudes or crudes with higher sulfur content. It is cheaper and easier to refine and produces a higher percentage of valuable products during the process, such as gasoline or kerosene for airplanes. No wonder that ExxonMobil describes its projects in Guyana as advantaged assets with the highest potential future value, to be prioritized in near-term capital spending.

Fiscal terms

But not everyone is happy. The contract that the partners in the Stabroek Block signed with the government has attracted significant attention. Some nongovernmental organizations and think tanks describe the terms as unfair to the government. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was quoted as recommending a revision of the fiscal terms, particularly the royalty rate, which stands at 2 percent, low by international standards.

While such a rate is indeed low – especially when the average oil royalty rate tends to be around 10 percent – international comparisons should be treated with caution, particularly when it comes to fiscal terms. Comparing individual headline rates often leads to simplistic conclusions, and one must also consider both the entirety of the fiscal regime and the prevailing conditions when it was designed.

Resource riches can be empowering when they arrive, but the question is what follows.

Additionally, Guyana’s case is typical of a predictable pattern in the evolution of fiscal terms. Especially in untested offshore environments, governments are likely to adopt a cautious attitude. They offer attractive fiscal terms to arouse sufficient interest from international oil companies and to kick-start activity. Once commercial discoveries are made, increased interest from investors may result in a tightening of the fiscal terms, particularly for new licenses. Renegotiation of existing licenses is not recommended; while bringing them under the new fiscal terms is possible, the process is not straightforward and requires clear rules, especially for the treatment of past expenses.

While there is no universal metric for what constitutes an appropriate block size, a simple international comparison indicates that the size of the Stabroek Block is unusually large. In Brazil, for instance, blocks tend to range from 586 to 1,373 square kilometers. However, here too, one could argue that Guyana opted for such a generous offer to appeal to investors and compensate for the high geological risk. Still, this may not remain the norm for future license allocations, now that the oil and gas potential has been proven.

Guyana’s trajectory

On a macro level, the oil discoveries in Guyana have put the economy on an entirely new path, with an impact already being felt. Guyana’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth rose from 5.4 percent in 2019 to 43.4 percent in 2020. The IMF expects it to hit nearly 50 percent in 2022, after a temporary slowdown (16.4 percent) in 2021. Of course, like everyone else, Guyana suffered from the pandemic – directly through the health crisis and indirectly through its impact on the oil and gas industry and prices. The IMF initially expected the country’s GDP to hit 86 percent in 2020. Still, the revised numbers eclipse everyone else’s performances.

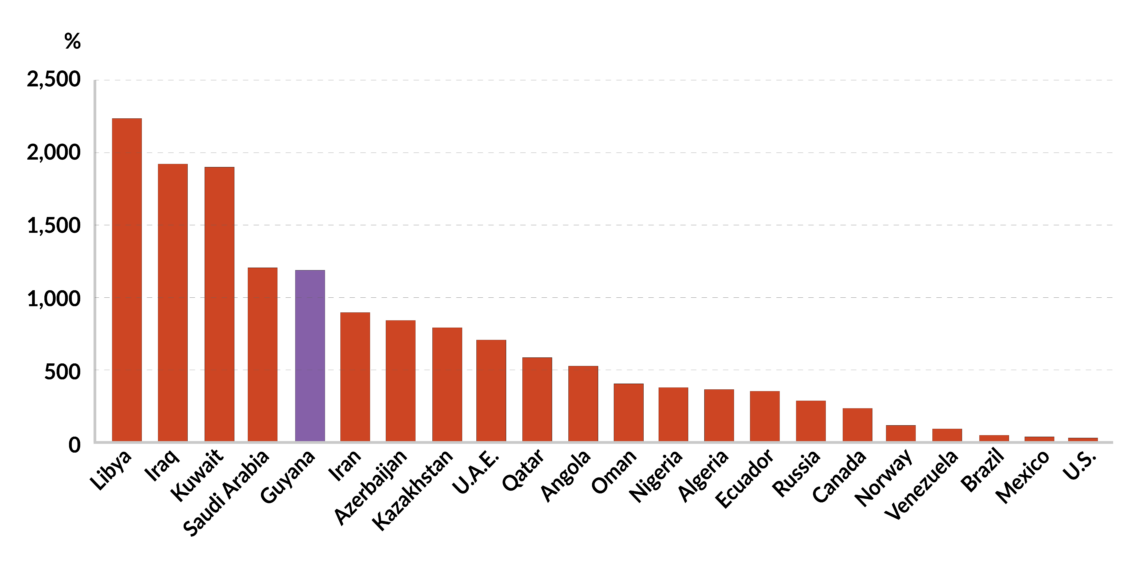

Furthermore, from the development of two discoveries in the Stabroek Block alone, the IMF forecasts Guyana to be on par with the world’s largest oil producers, regarding the value of those reserves to GDP.

Facts & figures

For a population of 800,000, one can only imagine the subsequent transformation the new wealth will bring. But this is also a reason for concern. Managing oil and gas revenues has presented a daunting challenge for many countries; resource riches can be empowering when they first flow in, but the question is what follows.

In many developing countries, those riches have failed to translate into economic growth and sustainable development, which are needed to create jobs, reduce poverty and provide basic services such as health and education. One would expect that countries endowed with oil and gas resources are the envy of their neighbors; instead, significant empirical evidence has shown that countries rich with hydrocarbons (and minerals) often grow more slowly than resource-poor nations. Experts have labeled this phenomenon the “resource curse” or “the paradox of plenty” – resource-rich, economically poor.

One can only hope that with so much evidence accumulated from around the world, Guyana will tread carefully and follow useful lessons from the experiences of others. Some encouraging steps are already being taken, including a sovereign wealth fund – set up in 2019 as the Natural Resource Fund– to manage the resource wealth, and save it for rainy days and benefit future generations. Still, the stakes are high and significant work remains to improve governance of and within the hydrocarbon sector.

Outlook

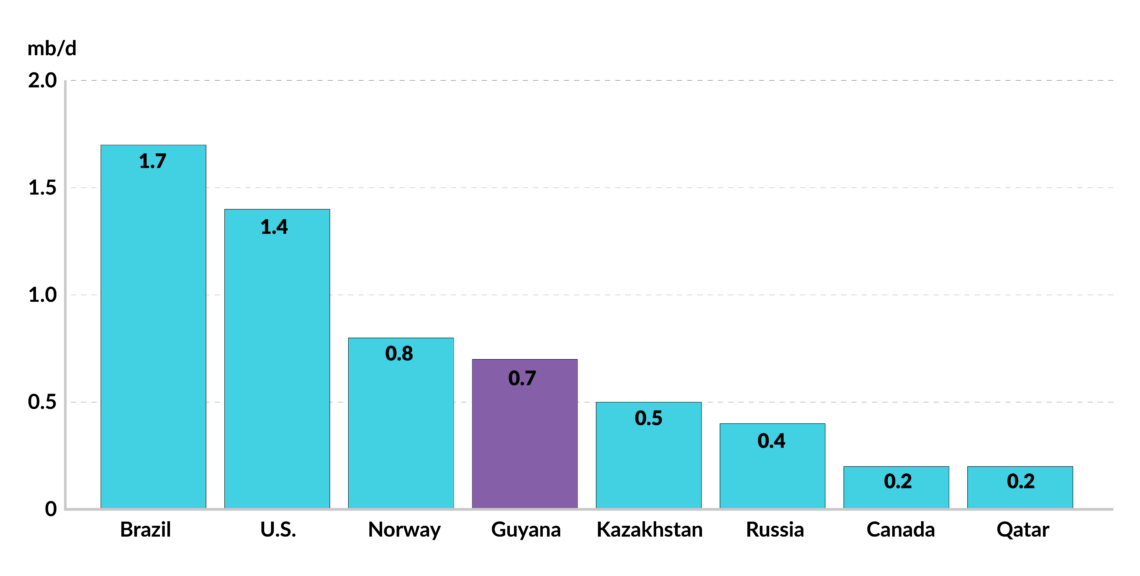

Guyana is expected to be one of the main contributors to oil supply growth outside OPEC by 2025, after Brazil, the U. S. and Norway. By then, Guyana is set to contribute around 700,000 barrels per day. Beyond 2025, the producers’ group sees Guyana as one of a few non-OPEC producers (including Canada, Qatar and Kazakhstan) showing meaningful supply growth. It will be interesting to see whether Guyana will be tempted to join OPEC. Guyana’s potential could even be much higher. However, as OPEC states in its World Oil Outlook published in 2020: “until the country has absorbed its newfound oil income politically and economically – and on top of the current uncertain outlook given the COVID-19 pandemic – we are reluctant to project higher growth.”

For a population of 800,000, one can only imagine the subsequent transformation the new wealth will bring.

Opposition to existing and new oil and gas activities is expected to continue. Even if economic concerns are appeased, climate change and environmental concerns will intensify. In a first of its kind case in the Caribbean, on 26 May 2021, two Guyanese citizens filed a lawsuit before Guyana’s Constitutional Court, challenging oil and gas production on the grounds that it violates the government’s legal duty to protect the rights to a healthy environment, sustainable development, and the rights of future generations.

Guyana’s oil story is still unfolding. So far, the start has been bright, as is its outlook. Even if oil demand peaks as the energy transition to a greener future accelerates, Guyana has a good chance of being among those last standing, with the scale and competitiveness of its resources. The oil wealth generated, if well managed, can support the development of the country for generations to come and long after oil’s importance to the global economy has dwindled. The investment climate has been attractive for international capital even under globally dire conditions. It is, however, too soon to forecast a straight path to happiness – too many critical policy choices have yet to be made, and too many pitfalls still loom along the way.