With import ban, Modi seeks more arms made in India

With a new import ban on 101 kinds of weapons, Narendra Modi is continuing his quest to expand the domestic arms industry in India. The lack of arms manufacturing has been a concern since the 1960s. Despite criticisms, the latest efforts are bearing some fruit.

In a nutshell

- India is expanding its domestic arms industry

- Firms on the low end of the market should succeed

- India still lacks certain technology and expertise

On August 11, the government of Narendra Modi announced an import ban on 101 varieties of weapons and military equipment to India, with rolling cut-off dates that extended to 2025. The announcement did not attract much attention, as most of the items were already being manufactured domestically.

However, Indian officials say the list will be expanded, and that even for weapons already made in India the level of indigenization required would be increased over time. The message: despite recent border clashes with China, Prime Minister Modi is not backing down from plans to create a broad-based domestic arms industry over the next several years, and so companies, Indian or foreign, should plan accordingly.

Background

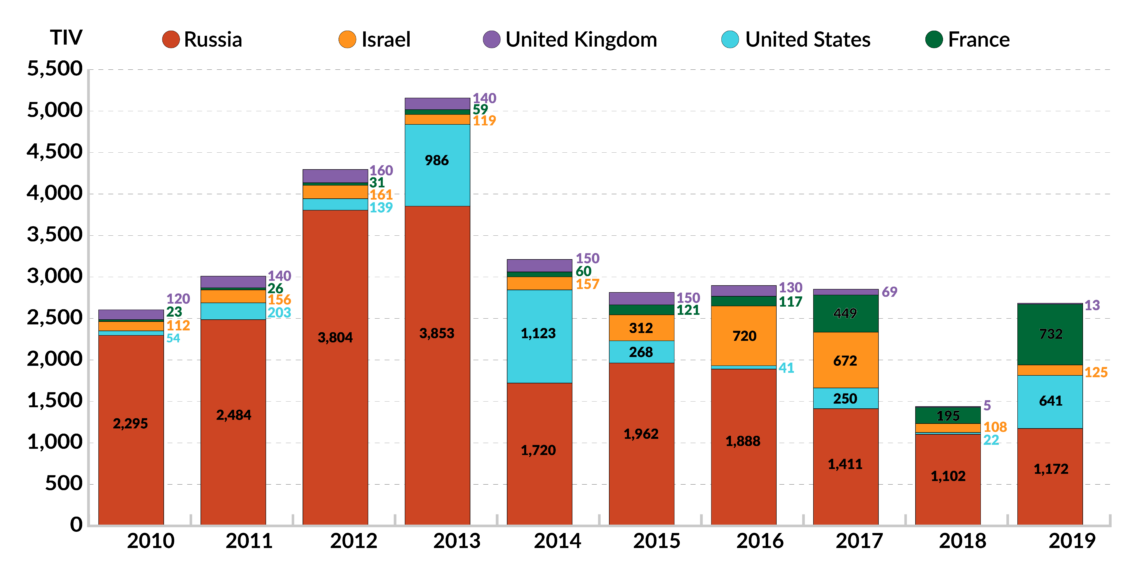

Since the 1960s, the Indian establishment has fretted about the country’s lack of arms manufacturing capacity and the constraints that places on its aspirations to be a great power. India has a sprawling, state-owned defense sector, whose endless quality problems has not earned it much credibility with the military. The private sector has stayed away from defense because of India’s complex and painfully slow arms procurement processes, and because of the country’s history of corruption in arms deals. As a consequence, India is among the world’s largest weapons importers. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute calculates that India was the second-largest importer of arms between 2015 and 2019.

The Modi government has harbored plans to boost domestic manufacturing through a mix of market reforms and state diktat. Ensuring that India reduces its dependence on foreign weapons fits neatly with the prime minister’s “Make in India” program, recently updated after the pandemic to “Self-Reliant India” (“Atmanirbhar Bharat”). As soon as he was elected in 2014, Mr. Modi began promoting the private defense sector, squeezing state-owned firms, cleaning up procurement procedures and forcing the military to accept some domestic weapons – even if they were inferior to foreign counterparts.

The days when India imported its soldiers’ helmets and boots are over.

India announced a Defense Procurement Policy in 2016 that laid out five levels of arms production with differing levels of domestic involvement. The most ambitious was a “strategic partnerships” plan for submarines, fighters and large platforms, that would require foreign bidders to work with private Indian firms all the way to the subcontractor level. In return, the foreign vendors would receive a slice of the multibillion dollar purchases, spread over several years.

These initial reforms faced considerable pushback, including from the military, labor unions and the economic nationalists within Mr. Modi’s own party. However, the bigger obstacle was Indian private sector’s lack of technical skills and financial reserves. Lastly, skirmishes with Pakistan in 2019 and bloody border clashes with China early this year led India to make billions of dollars’ worth of emergency military purchases and fast-track shipments of French Rafale fighters, American assault rifles and Israeli drones.

Facts & figures

Import ban

By announcing the import ban, the Modi government sought to end questions about the future of the indigenization policy. There was a desire to reassure India’s roughly 10,000 medium-sized and small defense firms – many of which have been battered by the Covid-19 economic slowdown – that they would be guaranteed opportunities to win contracts and grow.

Indian officials believe that, for all the criticisms, some early signs of success are visible. There are now several Indian-based and Indian-owned artillery and armored-vehicle manufacturers, missile and rocket makers, and a growing ecosystem of defense-oriented software firms. Greater managerial autonomy also meant some of the state-owned firms had begun to deliver. The 2016 policy’s second level of defense indigenization – known as Make 2, in which Indian firms license technology or import components to make larger weapons systems – has seen several successful ventures. The government says part of the reason for the import ban is to pressure the military services and the defense sector to search for technical solutions and corporate partners.

The government is confident India will make the most of its armor, including tanks and artillery, within the next three to four years. The hulls and propulsion systems for most of its warships are already homebuilt. New Delhi has its eye on submarines and helicopters as the next step in the Make in India campaign, and they are the first systems under the strategic partnerships policy. India’s ambitions to make advanced fighter aircraft, sophisticated drones and air defense systems are seen as aspirational and are notably not on the import ban list. They are also too crucial from a security perspective, given the state of tensions along India’s western and northern borders.

More forward-looking are programs like iDEX, a seed-funding scheme for defense start-ups, as well as investments in big data, artificial intelligence and network-centric warfare. The new policy is likely to benefit smaller, more agile defense firms from Europe, Israel and South Korea who are willing to share technology in return for license fees or a share of sales. Russian firms have a long-standing presence in India but dislike working with private firms.

The United States has the best technology and the biggest price tags – but, damagingly, the most regulatory red tape and restrictions. India will buy advanced weapons directly from Washington and Moscow for geopolitical reasons, but it is likely the companies from these countries will find it hard to align with Make in India. However, the strategic partnerships are lucrative enough to have attracted interest from even Lockheed Martin and Sukhoi.

Scenarios

Over the next five years, domestic manufacturers will begin to dominate the lower end of the Indian defense market. The days when the arms industry in India depended on imported helmets and boots are over. In the next few years, tracked vehicles and transport for the army and land forces will all be manufactured in India; that situation already exists with its naval platforms. The big developments in the near future will be in the realm of short- to medium-range missiles and guided munitions. The real test will be whether India can, over the next decade, also do this in areas where it has minimal manufacturing experience, notably submarines and helicopters.

The most important constraint will be creating enough Indian defense firms capable of handling the enormous capital costs of weapons making – a problem aggravated by India’s slow procurement system and tendency to cut defense expenditure whenever its budget comes under pressure. At present, there are only about half a dozen such private firms with a market capitalization over $1 billion, and about the same number of state-owned companies with similar capacities.

The ecosystem of smaller subsystems needs to be at least 10 times larger. It will take a decade or more before the Indian defense corporate sector reaches critical mass. This is exactly why indigenized military production is likely to plateau after several years. The even more difficult issue of developing a defense-related research, development and application cycle – let alone mastering the most difficult elements of cutting-edge technology like systems integration – is even further away. After all, this has yet to be achieved in India’s civilian industrial sector.