India-Europe ties grow closer

The rise of China and changes in the U.S. policy have presented huge challenges for Europe and India. Their interests align with issues such as international trade and climate change. In the face of Brexit, India seeks partnership with other EU countries.

In a nutshell

- Europe and India have concluded they need closer relations

- The rise of China and Trump accelerated that process

- Climate and trade are key potential areas of cooperation

- Future ties could depend on the U.S.-Europe relationship

Over the past few years, relations between India and Europe have been growing closer thanks to the United States and China posing new challenges to the international order. Europe and India are both alarmed at President Donald Trump’s unilateralism and China’s assertiveness. Common concerns over climate change, international trade and the provision of other global public goods have led New Delhi to align more closely with Europe. Brexit has added impetus to the growing ties, forcing India to seek partners in Europe other than the United Kingdom. The European Union, in turn, has accepted that it must engage strategically with India.

Trump’s impact

India and the EU had begun reevaluating their relations even before President Trump was elected in 2016. Brussels had concluded its relations with India was stuck in two ruts: human rights and trade negotiations. It was able to restrain its language on India’s patchy human rights record, helped by a winding down of the violent insurgencies in Kashmir and India’s northeast. It also decided its pursuit of a free trade agreement was impractical as long as India believed its ailing manufacturing sector needed tariff protection.

The UK’s vote to leave the EU in June 2016 led India to search for new partners in Europe. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a state visit to Berlin in May 2017, he added Paris to his agenda to meet the newly elected French President Emmanuel Macron. He also became the first Indian leader to visit Spain in nearly three decades. Indian diplomats said they sought new relationships among EU members in expectation of a British withdrawal.

India, while troubled by President Trump’s actions, also saw opportunities in his upending of the international status quo.

The election of President Trump was a huge shock for Europe. The U.S. leader’s worldview held that the country’s existing network of security alliances and multilateral agreements did not comport with American interests. Two elements were particularly jarring. One was his hostility to the Atlantic alliance, including NATO and the EU.

The other was a mercantilist view of trade that saw deficits as detrimental to a nation’s economy. In President Trump’s view, the rule-based international trading system embodied by the World Trade Organization (WTO) ran counter to U.S. economic interests. He thus not only broke with the postwar American foreign policy consensus but went well beyond the traditional Republican policies.

India, while troubled by President Trump’s actions, also saw opportunities in his upending of the international status quo. New Delhi quietly applauded the initiation of a trade and technology war with China. President Trump’s policies also meant China’s expanding strategic footprint across Asia now faced some genuine resistance.

India was less invested in the international system. Its trade and security policies were inward-looking because of a deep belief that its domestic problems meant it had to limit its overseas activities. New Delhi also believed many international fora, notably those governing nuclear nonproliferation and multilateral finance, were discriminatory.

Climate issue

In 2017 President Trump roiled India and Europe by announcing the U.S. was pulling out of the Paris Agreement on climate. There was a debate in New Delhi as to whether India should follow suit due to Western countries’ failures to live up to their environmental pledges. Prime Minister Modi, who takes a special interest in climate, decided to stay the course out of fear the Paris Agreement would unravel. His decision was also in line with the strong environmental streak in the prime minister’s religious-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, reflecting the animistic origins of Hinduism. The decision helped seal a budding relationship between Prime Minister Modi and President Macron. Brussels made climate a central pillar of the new India-EU relationship.

Facts & figures

Growing partnership

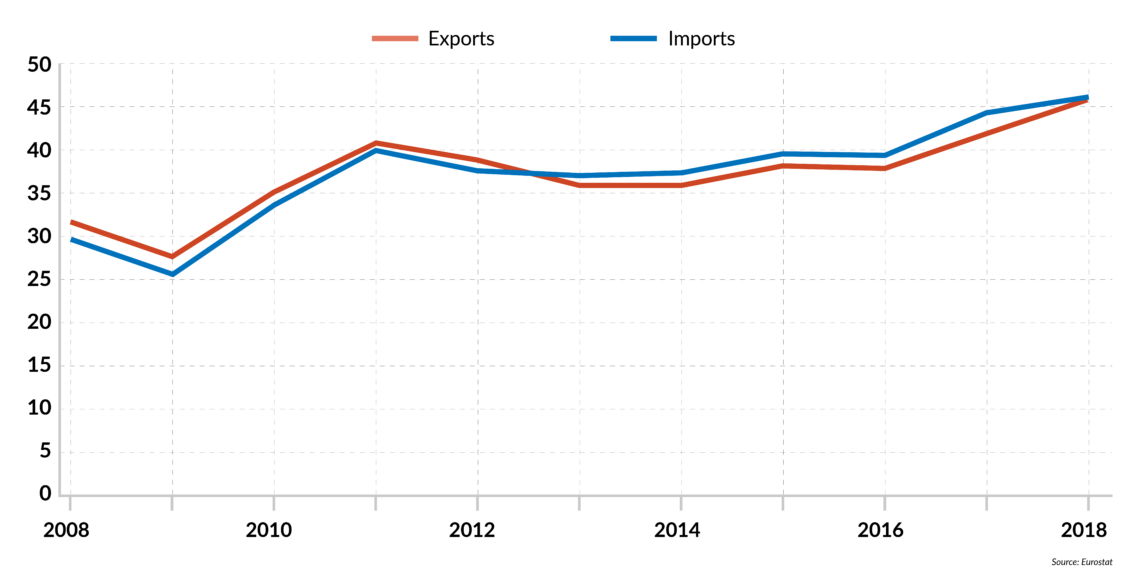

European Union-India trade (euro billions)

Indian and European interests do not overlap on all multilateral issues as neatly as they do on climate. A case in point is global trade. India supports the WTO but sees China as a troublemaker in the organization. During his first term, Prime Minister Modi decided to freeze all Indian trade negotiations, including those with the EU, leading Brussels to conclude it was more profitable to coordinate with other countries, like Japan. Though the two also opposed President Trump’s imposition of economic sanctions against Iran, India sought an exception for its Iranian oil imports once it became clear that Europe’s talk of finding a means around U.S. financial barriers would not bear fruit.

India and Europe did hold talks about maritime security, a big concern of major trading states like Germany, but they soon reached a dead end because neither had large enough militaries to cover the geographical interests of both parties.

India’s security interests center around Asia, while Europe tends to be more concerned about the Atlantic. New Delhi has thus restricted its military cooperation to France, the only European state with a permanent defense presence in the Indo-Pacific. Even its first EU naval exercises were with double-flagged French warships. Similarly, the Modi government supported President Trump’s decision to abrogate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty because it believed the move would free the U.S. to deploy medium-range missiles around China. New Delhi shares none of Europe’s worries about Russia.

On trade, nonproliferation and maritime security, India believes that Europe is not a major Indo-Pacific player.

The EU’s most recent India strategy paper, released in November 2018, reflects this newfound worry about the future of the international system – as well as the limits to India-EU cooperation. Working together in climate, energy security and the United Nations receive top priority.

Trade, nonproliferation and maritime security are more about principles than practice. In the latter fields India prefers working with individual European countries and, even then, its actions are influenced by the belief that Europe is not a major Indo-Pacific player.

The EU’s strategy paper also considers the possibility of India-European cooperation in third countries in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere, something India is already doing with Japan.

Scenarios

While cooperation between India and Europe can only be on an upward trajectory, the question is how far and fast the curve will rise. The present path, defined by the first Modi term, will center around climate change and supporting existing multilateral bodies. India remains skeptical that any EU member state – despite the strategy paper calling for “a multipolar Asia” – has the will or means to constrain China. Washington and Tokyo will remain its primary strategic partners in Asia. Europe will assume India is too protectionist to help support the international trading system.

A negative scenario would hinge on the European response if a more orthodox president of the U.S. is elected next November. Europe’s leaders could return to transatlantic business as usual and roll back their cooperation efforts with lesser powers. Indian and European collaboration would potentially even regress to what it was five years ago, exacerbated by European uneasiness at Prime Minister Modi’s religious nationalism. New Delhi might then revert to its old policy of maintaining relations with a few European countries, ignoring Brussels and cutting Europe out of its strategy.

An optimistic scenario will depend on how much the Modi government is prepared to open up to trade. There are indications that New Delhi, recognizing the failure of five years of protectionism, plans to change tack on trade policy. Prime Minister Modi, for example, recently commissioned a report on improving India’s competitiveness and is using this as a template for his next wave of economic reforms. The report remains outside the public domain but is known to take a strong free-trade position

India is also increasingly conscious of the dangers of receding U.S. power in areas beyond hard security, such as energy security and financial markets. New Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, to the surprise of European diplomats, showed up at the United Nations multilateralism session last month and warned of the “Kindleberger trap” – a theory that international stability’s greatest threat will be the failure of middle powers to offer the global public goods once provided by the U.S. This is evidence that the ground is being laid for a post-Trump world if India, Europe and others can convert intent into action.