India decides on force to break a pointless cycle

The latest round of fighting on the India-Pakistan border reveals a changed mood in New Delhi. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to order an airstrike deep inside Pakistan is evidence of a more muscular policy taking shape in India. If Mr. Modi is reelected, India will likely be brandishing a bigger stick at its Western neighbor.

In a nutshell

- India’s government now seems committed to a harder line against Pakistan

- The new doctrine has cut off talks and calls for mandatory retaliation to terrorist attacks

- Not all in New Delhi are happy with this course, which will soon be verified by elections

India appears to have changed its tactics in the latest round of fighting with Pakistan. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to order an air strike deep inside Pakistani territory in reprisal for a terrorist attack is evidence of a more muscular policy taking shape in New Delhi. If Mr. Modi is reelected in a few months, it can be assumed that India will be brandishing a bigger stick at its western neighbor.

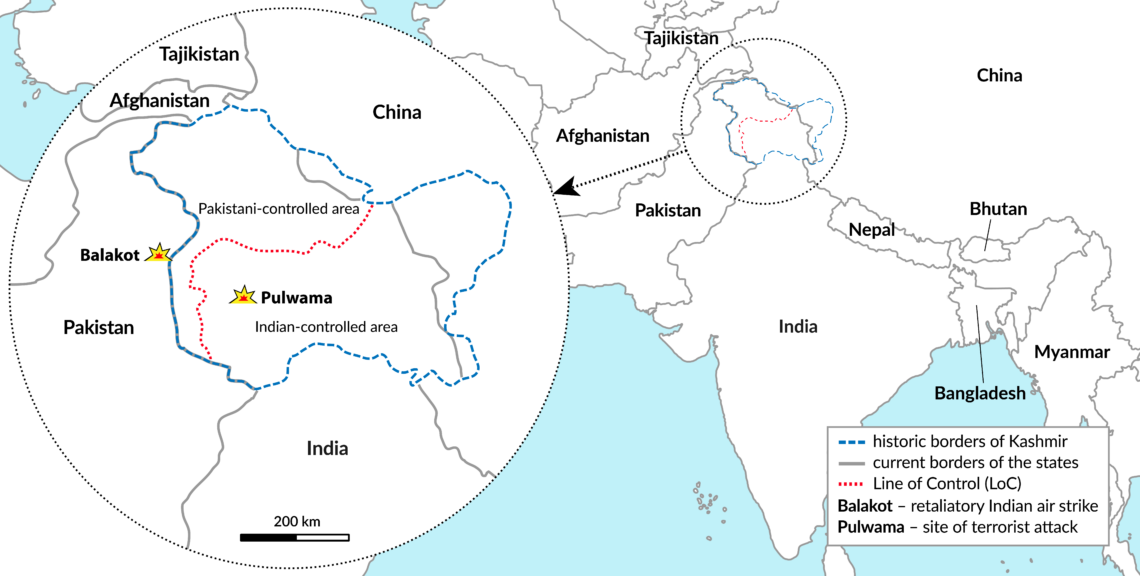

The present crisis began when a suicide bomber killed 40 Indian security troops in Indian Kashmir on February 14. Jaish-e-Mohammed, a Pakistan-based terrorist group, claimed responsibility. Twelve days later, Indian fighters bombed what New Delhi said was a Jaish camp in Pakistan’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. Pakistani fighters retaliated by dropping bombs on Indian soil the next day. In the ensuing dogfight with Indian warplanes, each side claimed to have shot down a fighter.

With New Delhi and Islamabad each claiming victory and the international community calling for restraint, the air war was quickly shut down. Both sides continued artillery shelling along the unofficial Line of Control (LoC) between the two halves of Kashmir, but such harassing fire is a routine event between the two armies. Outwardly, everything appeared in line with what India and Pakistan have practiced for decades. But that overlooks a significant policy shift in India that has been underway for several years.

Sterile pattern

After his conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the 2014 elections, Prime Minister Modi chose as his national security advisor Ajit Doval, the ex-head of the domestic intelligence agency and a known hawk on Pakistan. Mr. Doval and like-minded people in India’s national security community insisted that the bilateral relationship with the authorities in Islamabad had fallen into a sterile pattern. The leaders of the two countries would launch a peace process, which would sputter along for a while until Pakistan-based terrorists attacked India; talks would then be called off until things calmed down and another short-lived round of dialogue could start, to be interrupted by the next attack.

Mr. Doval urged India to drop talks with Pakistan entirely, unless something big might be accomplished.

According to Mr. Doval, this cycle had become internalized on both sides, even though it achieved nothing and India was always on the receiving end of new terrorist attacks. Privately, he described the whole process as the “left hand washing the right hand as the right hand washes the left.” Confirmation of this official mindset was provided by the outgoing government of Manmohan Singh (2004-2014), which in its recommendations to Mr. Modi’s incoming cabinet advised that there was nothing to be done about Pakistan. “Just keep talking and work for the occasional pause in violence,” was their advice.

Mr. Doval’s own recommendation was that India drop the dialogue entirely unless something substantial might be accomplished. The government should also be ready to carry out limited military retaliation every time India suffered a terrorist attack. These proposals faced considerable resistance within India’s policy establishment, which saw this course as risky both militarily and diplomatically.

Modi’s choice

India’s new leader decided to adopt the first part of the policy and abandoned formal dialogue with Pakistan. Starting with his own inauguration, he was careful to meet his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif, only in a multilateral context. During his five years in office, Mr. Modi has traveled to Pakistan only once – and that was for a surprise personal visit to a wedding in Mr. Sharif’s family. The prime minister has an ingrained dislike for diplomacy that fails to yield concrete results, and his Hindu nationalist political base is hostile to even photo ops with Pakistani leaders.

There were good reasons for Mr. Modi to stop short of a policy of military retaliation, however. Terrorist attacks on Indian soil were at a low. The normally turbulent state of Kashmir was quiet and the state government of its Indian-controlled part was a coalition of Mr. Modi’s own BJP and a local Muslim party. Moreover, the prime minister was a fiscal conservative disinclined to spend large sums on weaponry. Over the next five years, in fact, he froze defense spending, allowing it to drop to 1.55 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017-2018, the lowest recorded since 1962.

Facts & figures

Striking back

On top of everything else, Mr. Modi took a personal liking to the affable Pakistani prime minister. Privately, he was known to lament that “[Nawaz] Sharif has all the right ideas, but his military will not give him any authority.” Until Mr. Sharif was removed from office by Pakistan’s supreme court in 2017, in the wake of a financial scandal, Mr. Modi went to pains to avoid undermining him in public.

In keeping with this policy, the Indian government treated a 2015 terrorist attack that killed seven in Gurdaspur, Punjab, as an exception – even though New Delhi identified the perpetrators as members of the Pakistani-based Lashkar-e-Taiba group. However, a much more ambitious attack on Pathankot air base in January 2016 could not be ignored. Had this raid been successful, dozens of warplanes and helicopters would have been destroyed on the ground.

India had tipped off Pakistani about intelligence that Jaish-e-Mohammed was planning a major attack, but Islamabad did nothing to impede the terrorist. After Pathankot, Prime Minister Modi was ready to accept both parts of Mr. Doval’s new doctrine. Hard-nosed military options were drawn up.

Green light

In September 2016, Jaish gunmen attacked an Indian army post in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, near the town of Uri, killing 17 soldiers. Casualties on this scale had not been seen in nearly two decades. Mr. Modi authorized reprisal. Twelve days later, India announced its special forces had crossed into Pakistani Kashmir and killed a large number of terrorists in their camps. Pakistan prudently denied that the attack had taken place, which ensured that escalation would not follow.

Islamabad’s reaction also underlined that nuclear-armed India and Pakistan had, over the years, established a pattern of limited military confrontation that did not cross the nuclear threshold. This is now so well recognized that it has been dubbed the “stability-instability paradox” by international relations scholars.

The policy of no negotiation, only retaliation has now become ingrained in the Indian government.

However, Mr. Doval’s new policy was now ingrained in the Indian government. There would be no negotiation, only retaliation. The national security advisor understood that his new policy would take time to become internalized in both India and Pakistan. All this was helped along by an uptick in civil unrest in Indian Kashmir from 2016. Two years later, the coalition government in Kashmir fell apart.

India also noted another consequence of the Uri attack: Pakistan was unusually isolated internationally. Four countries had traditionally given Islamabad diplomatic cover: the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and China. Of these, only China continued its support for Pakistan, while the others had adopted either a neutral or hostile attitude. Saudi Arabia had already pleasantly surprised India by providing intelligence on the identities of the Pathankot attackers. Now, instead of following their usual practice of apportioning the blame equally between Indian and Pakistan, foreign governments were increasingly siding with the former.

A contributing factor may have been lessons learned from the past several armed clashes between India and Pakistan. The major powers appear to have concluded that barring a full-scale war, neither side would resort to its nuclear deterrent. According to this view, limited border fighting did not constitute a nuclear threat.

All of this paved the way for the Indian response to the Pulwama attack on February 14, 2019. Pakistan’s new prime minister, Imran Khan, was perceived by the Indian side as weak and dependent on army support. When New Delhi warned Washington, Riyadh and other capitals that retaliation was inevitable, its emissaries received what they regarded as a green light.

India’s armed response was notable on three counts. First, the attack came from the air. Second, it was made in considerable strength, with news reports indicating that more than a dozen warplanes were involved. Finally, India broke with its earlier practice of not striking Pakistan proper. In the past, reprisals had been limited to Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, an area India claims as its own. This had always allowed New Delhi to adopt the pretense that it was striking its own territory, and thus not engaging in an act of war.

What next

Several scenarios could ensue from this new state of affairs.

Most likely, periodic outbreaks will continue between the two countries – fewer perhaps, but more intense than before. Pakistan will be unwilling to fully rein in the terrorist groups for fear of losing its main leverage to get India to negotiate. With the U.S. looking to withdraw from Afghanistan, the Pakistani intelligence agencies will also have large numbers of idle jihadi fighters to deploy. Some reports already attribute the recent increase in Jaish activity to an infusion of ex-Taliban recruits.

As India modernizes its military, terrorist attacks may become less frequent, but bigger and more deniable.

Over time, India’s ability to hit back will also increase as its arsenal is modernized with a new generation of fighters, armed drones and “smart” artillery. This will force Pakistan to be more calculating in its attacks and more sensitive to the international context. Terrorist attacks may become less frequent, but bigger and more deniable.

Another possibility is that India may simply abandon Mr. Doval’s retaliation strategy and revert to the old talk-and-terror cycle. The Modi government installed its new policy only three years ago; many in the foreign policy and security establishment remain unconvinced that the risks are worth it. India’s next general election is less than two months away, and the opposition Congress Party has traditionally preferred dialogue to military action. Given these circumstances, Pakistan has every incentive to wait and see whether the new approach outlasts Prime Minister Modi’s tenure.

Perhaps the least likely scenario is that peace will break out. Pakistan’s economy is struggling and its patron, China, has little interest in underwriting its territorial squabbles with India. If Mr. Modi or his successor feels in a few years that India is strong enough to reopen a dialogue with Pakistan, the right doors could align at the right time. However, for now that possibility belongs more to the realm of wishful thinking than reality.