India wades carefully into the Western Pacific

Since the 1990s, India has been strengthening its role in the Western Pacific. While it will continue to use its relationships with the United States, Japan, Singapore and Australia to strengthen its position, India must also be careful not to earn Beijing’s ire.

In a nutshell

- India is coordinating with the U.S., but keeping its options open

- Its other partnerships in the Pacific aim to balance China

- New Delhi wants to refrain from provoking Beijing

Since 1991, India has been emerging as a force in the Western Pacific. The evolution has been slow, but significant nonetheless. Its gradual, careful nature is its most salient feature. India’s influence in the region will continue to grow, but it takes a long-term perspective and an appreciation of India’s unique position to understand its importance.

India has an overwhelming impulse toward autonomy in developing its foreign policy. While all countries want to maintain sovereignty in their decision-making, it is an imperative with especially deep roots in India. Unlike many other similarly driven countries, India’s size and location give it the wherewithal to act more independently.

India’s big-country frame of mind means its key partners in the Western Pacific – the United States, Japan, Singapore and Australia – sometimes find cooperation with New Delhi challenging. The degree to which they can maintain their patience (and in the U.S.’s case, its general commitment to the region’s security) will determine India’s geopolitical role in the region.

Facts & figures

The US: Unique security partner

The U.S. is accustomed to unbalanced Pacific alliances. It is the guarantor of security in Northeast Asia by virtue of its major military presence there. That U.S. allies depend so much on it for their security leads Washington to test the boundaries of relationships in ways that would otherwise be unacceptable.

There are several examples of this behavior worth mentioning. One is the sustained U.S. military presence in Okinawa, Japan, despite local opposition. Another is American demands that South Korea increase its support for U.S. bases there – demands that will soon be replicated in negotiations with Japan. Then there is the repeated renegotiation of the 2007 U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement and the hard bargaining the Trump administration has pursued with Japan over trade issues.

India talks to Washington about broad strategic concerns like China, while keeping its options open.

India, by contrast, is closer to Southeast Asia’s current disposition regarding U.S. power. American sway in Southeast Asia is extenuated by distance from its bases in Japan, Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast. Indeed, Washington’s already limited room for maneuver with its allies in the Philippines and Thailand seems to be shrinking.

With India, the U.S. has even less leverage. It has no security treaty with India and is an ocean away from where its military has been most heavily involved since 1945. The U.S. also has a history of close relations with Pakistan that is only just beginning to fade in the calculations of Indian analysts and politicians.

India talks to Washington about broad strategic concerns like China, while keeping its options – including working with Beijing – open. India will never commit to an arrangement that binds it to decisions made in Washington. However, it will cobble together functions for security cooperation with the U.S.

Facts & figures

‘Foundational agreements’

The U.S. enters into four “foundational agreements” with its closest defense partners. These are:

1. The General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA)

2. The Logistics Support Agreement (LSA)

3. The Communications and Information Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMOA)

4. The Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) for Geospatial Intelligence

India has signed the first three: GSOMIA in 2002, an India-specific LSA called the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) in 2016 and in 2018 it signed the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA), which is an India-specific version of CISMOA.

India has concluded three of the four “foundational agreements” for sharing military-related information and logistics that the U.S. has with its closest allies. It is working on the fourth (see box). The two sides have a concerted program for cooperating on military technology development, in addition to private-sector collaboration through India’s purchase of more than $20 billion in U.S. equipment. For many years, India’s military has exercised more with the U.S. military than with any other in the world. New Delhi also loosely coordinates diplomatic statements with Washington on principles underlying the regional order, like freedom of navigation and Indo-Pacific strategies.

Japan: Search for balance

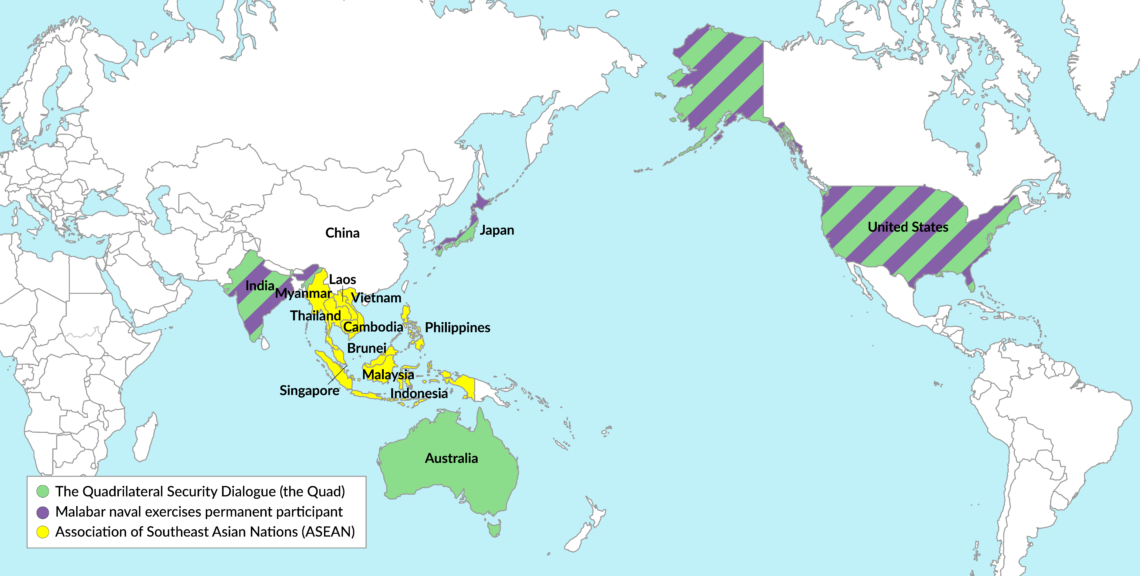

Concern about China also brings India and Japan together. New Delhi’s relationship with Tokyo encompasses a wide range of regular government bilateral dialogues, including a 2+2 meeting among their defense and foreign ministers. India holds only one other such regular meeting – with the U.S. There is also an active trilateral diplomatic dialogue involving the U.S. and Japan and a quadrilateral security dialogue that brings in Australia (known as “the Quad”).

These engagements send important signals and facilitate more concrete interaction between India and Japan. The two have foundational agreements on the exchange of military information similar to those each has with the U.S. The countries are working on an additional agreement to facilitate logistics support for each other’s navies. They also exercise together, most notably as part of India’s multinational Malabar naval exercises (see box).

Facts & figures

The Malabar naval exercises

Each year India, the U.S. and Japan participate in the Malabar naval exercises. In some years, other countries are invited to take part. The Malabar exercises began in 1992 as a bilateral initiative between the U.S. and India. In 2015, Japan was made a permanent participant in the drills. The operation has grown in complexity over the years. In 2019 it involved several ships and aircraft.

Singapore: Southeast Asian anchor

Singapore has served as a key Indian partner since ushering it into the diplomatic architecture of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Engagement through ASEAN was India’s channel for ending the estrangement from Southeast Asia that it endured during the Cold War for its rough alignment with the Soviet Union.

On India’s part, economic considerations mostly drove the move to improve ties with Southeast Asia. Singapore’s motivation for helping India engage with the region was mostly to balance Chinese influence.

Today, although Vietnam plays a vital role on the security side since it, too, heavily relies on Russia for military equipment, Singapore is India’s main economic diplomatic and security partner in Southeast Asia. Singapore has little land to work with, and India hosts Singaporean military training. The military services of India and Singapore regularly exercise together, including in the South China Sea. Their defense ministers hold regular dialogues.

Australia: Promising relationship

Of these four priority countries, India’s relationship with Australia has been the most politically fraught. It is, however, one with immense potential. Its promise is largely attributable to geography. Bordering the Indian Ocean as well as the Pacific, Australia is a maritime neighbor. Both countries are democracies concerned with the rise of China.

Until very recently, India-Australia relations were plagued by differences. New Delhi suspected Australia of being too economically dependent on China to be a reliable partner in countering it, and too close to Pakistan to be trusted. Meanwhile, incidents in Australia, like attacks on Indian students, aggravated substantive differences and often impeded efforts to repair and expand relations.

However, as U.S. engagement with India expanded, and as Australian concern over China has grown, Australia has become a more attractive partner. Since 2014, when Narendra Modi became the first Indian prime minister in 28 years to visit Australia, the relationship has blossomed.

In 2014, the two countries established a framework for security cooperation, and they are in the process of negotiating a military logistics agreement. The acknowledged “strategic partnership” between the two includes combined military exercises that are growing in complexity. Reluctant to provoke China, however, New Delhi has refused for many years to invite Australia to the Malabar exercises it hosts with the U.S. and Japan. New Delhi has seen such a clear display of security alignment with the U.S. and its allies as a step too far.

Scenarios

India’s primary geopolitical interest lies in the Indian Ocean and on its borders with China and Pakistan – two countries it increasingly sees as part of one strategic package. It has good reason, however, to “Act East” as Prime Minister Modi has called his policy approach to the Pacific. There are sizeable benefits to tapping into the economies of the Western Pacific. But by involving itself actively in China’s littoral, India also seeks to limit Chinese pressure on its northern border, to temper Chinese ambition in its relationship with Pakistan and to limit Beijing’s adventurism in the Indian Ocean.

Essentially, India is moving to the rear of its greatest potential adversary. However, it has limited resources to pursue priorities in all these areas simultaneously. It must therefore supplement its efforts by carefully managing its relationship with China. That necessity for a cautious approach limits what New Delhi’s partners can expect from it.

Scenario 1: The most likely scenario is the continued steady convergence of interests among India and its partners in the Western Pacific. Although most of these partners’ interests lie in the Pacific, not the Indian Ocean, they meet around the China challenge. These partners see a strategic value in engaging India as deeply as New Delhi will allow in addressing this issue together.

They will continue to be patient with India as it develops the capacity and will to “act east.” And they will continue to build a more robust security partnership. In the meantime, India will be eager to work with all four countries and others, like Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines and South Korea.

This scenario depends on the allies not pushing India too hard. It is not ready to risk a major confrontation with Beijing, and given China’s continuing military development, it may not be ready for many years. In the near future, India will shy away from doing anything to purposely provoke China. New Delhi’s Western Pacific partners recognize this. They will test the limits of Indian diplomacy in forums like the Quad, and on issues like the East and South China Seas, but ultimately defer to Indian sensitivities. Taken in historical context, it is already quite a stretch for India to be forging ahead with these four countries so closely associated with the U.S.

Scenario 2: The continuing rise of China is a given in both scenarios. U.S. policy is the most significant variable. Changes in the U.S. disposition will have the greatest impact on the efforts of the others. The trigger for the second, less likely scenario, is a U.S. withdrawal from the Western Pacific for reasons associated with domestic politics.

India’s interest in autonomy would not change. It would continue to resist the Chinese, but it would also have to focus more intently closer to home – on the Indian Ocean and its land borders. This scenario could also materialize if the U.S. were simply to lose its patience with New Delhi and disengage from the relationship or allow other issues like trade or India’s relationship with Russia or Iran dictate its approach.

Other partners in the region cannot offer India the comfort it needs to act freely to its east. Japan will continue as a major economic player, but given its constitutional constraints and continued penchant for pacifism, it is unlikely to lead a regional security response to China. Both Australia and Singapore lack the size to play such a role.

The Indians will continue strategic dialogues with these countries and others. They will continue to make port calls. But without the U.S. in the picture, these moves would lack strategic relevance. In such a scenario, the Chinese would gradually achieve their great power goals in the Pacific and press the Indians ever closer to home.