Southeast Asia’s future tied to great power competition

For years, China has combined skillful diplomacy with economic might to build partnerships in Southeast Asia. The U.S. has been more focused on security issues. The future of Southeast Asia depends on how the great power competition in the region will unfold.

In a nutshell

- China has the upper hand over the U.S. in Southeast Asia

- Japan, India and Europe all have interests in the region, too

- U.S. trade policy will be a key factor for the future of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is quickly emerging as the Asian epicenter of the United States-China great power competition. At the same time, several other outside players are also competing there, including Japan, India and Europe. All of these players’ approaches to the region will determine its geostrategic disposition and thereby the future of the broader Indo-Pacific order.

China’s rise in Southeast Asia

After a 100-year decline in influence, China is reasserting itself. This trend began during the era of Mao Zedong with expressions of third-world solidarity and support for communist insurgencies. China turned to more constructive policies when it tamped down its revolutionary fervor and began normalizing relations with the nations to its south. Then, empowered by its era of reform and motivated by the fallout after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, it deepened those ties. Since then, it has come to be seen as a reliable and valuable partner among countries in the region (perhaps with the exception of Vietnam, which has an especially complicated relationship with China).

China is now Southeast Asia’s leading force in trade. It is the third-largest source of investment in the region. It has had a free trade agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) since 2010 and is set to be the largest economy in the ASEAN-centered 15 nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Parallel to this growing economic position, since the early 1990s, China has become deeply involved in the full range of ASEAN’s diplomatic activity. It has also long cultivated close state-to-state relationships across the region. In some places, like Cambodia, it is particularly well-positioned. In others, like the Philippines, it is seizing new opportunities.

Economic contributions and diplomatic influence go hand in hand.

Economic contributions and diplomatic influence go hand in hand in Southeast Asia. It is economics, not cross-border security issues, that most concerns national governments there. For this reason, ASEAN is most substantively an economic organization. It represents a region largely of low- to middle-income countries in need of trade, infrastructure investment and development assistance. Few nations in Southeast Asia are willing to trade such tangible benefits for concepts of international order of no immediate relevance to them.

The Chinese approach is therefore a very good match for Southeast Asia. Its constructive diplomacy in the region, as well as the economic advantages it brings, have helped China weather clashes of interest with individual ASEAN members. Most prominently, these have involved the South China Sea and Beijing’s dominance over the headwaters of the Mekong River, as well as broader geopolitical concerns.

U.S. reaction

Southeast Asia has never mattered much to the U.S. strategically, except when influence over it was contested. It was a theater during World War II and during the Cold War. When the Cold War ended, the U.S. neglected it – most famously illustrated by its 1997 refusal to participate in the International Monetary Fund bailout of treaty ally Thailand in the midst of the Asian financial crisis. Throughout the 1990s, U.S. businesses saw commercial opportunity in Southeast Asia. The U.S. government, on the other hand, was more focused on human rights. Without a strategic competitor, the blind pursuit of American ideals carried little price. Maintaining strategic influence in the region was a distant priority.

That has changed. Today, U.S. policy toward the region is driven by an understanding of China’s accumulated and growing influence. American strategic documents are infused with great power competition, from the 2017 National Security Strategy to the Defense Department’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report to the State Department’s “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: A Shared Vision.”

Facts & figures

In substance, the approach to Southeast Asia is not all new. The administration of President Donald Trump is building on the security and diplomatic commitments of its predecessor – the “Asia rebalance,” and dispersal of military deployments south. In the process, it has intensified efforts around maritime issues.

First, in addition to its regular operations in the South China Sea, the Trump administration has conducted at least 19 Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea. That is several times more than the Obama administration carried out in its full two terms.

Second, the U.S. is seeking to “network” its maritime presence. This involves taking American allies and partners in the region through a continuum of security cooperation, from the detection of threats to sharing information to cooperation in problem-solving. The idea is to build a network around maritime surveillance.

The U.S. is helping several countries, including the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand, acquire technology to detect potential security threats at sea. These include piracy, sanctions-busting shipments to North Korea, illegal narcotics or fishing, or terrorist-related activity, among others. It could also be unusual Chinese activity involving its navy, coast guard or maritime militias. The U.S. then provides systems for sharing this information with Washington and other partners, hoping these countries will cooperate to address the problems they identify – with or without American assistance.

As China’s share of regional economic activity is rising, America’s is falling.

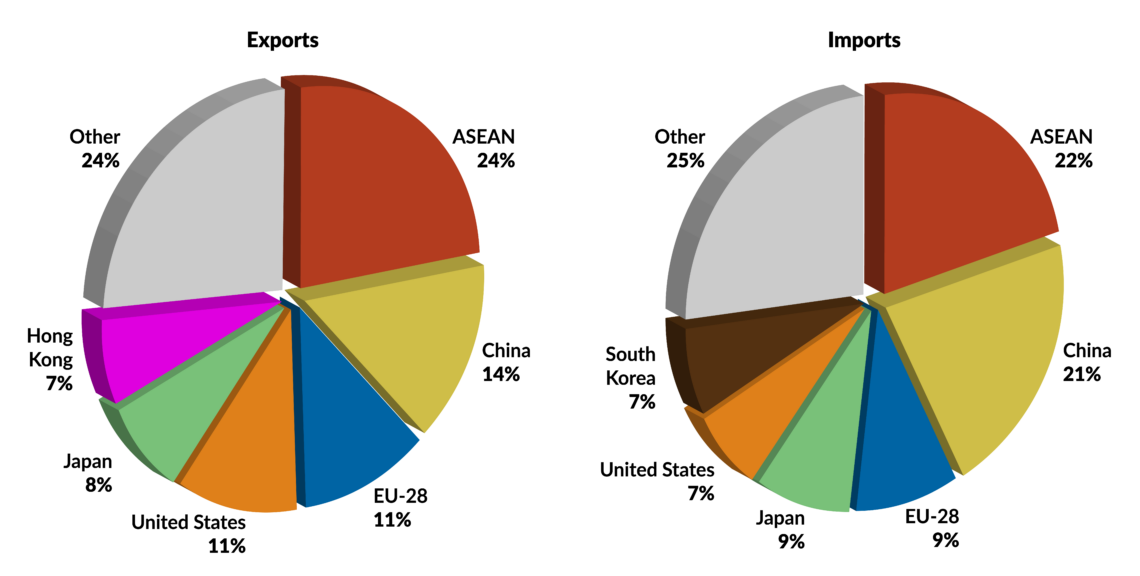

In economic matters, however, the U.S. is far less engaged. As China’s share of regional economic activity is rising, America’s is falling. It is both a smaller export market for ASEAN than China and a smaller source for the region’s imports. Moreover, since 2017, the flow of investment from the U.S. has shrunk to levels smaller than China’s (though the U.S. remains a larger net investor in the region).

As for economic statecraft, the U.S. pulled out of the meticulously negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP included four Southeast Asian nations and more are likely to join its new incarnation, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The U.S. is not eligible to join RCEP, which unlike CPTPP, includes China. It has a very successful free trade agreement with Singapore that has been in place for 15 years. But despite supposed prospects for bilateral agreements with Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines, no others are in progress.

Others in the region

There are several other important outside parties. They are secondary powers because they do not have the full range of diplomatic, military, and economic capabilities that major powers do. However, their actions will still have a significant impact on the region.

Japan has long been an economic powerhouse in Southeast Asia. It is the region’s second-largest export market, behind China. Countries there trust Japan and view it in a positive light, both because of its economic profile and its efforts since the late 1970s to engage with partners in noneconomic ways. As a matter of policy, it has expressed support for universal values and a rules-based order, is heavily engaged in ASEAN’s diplomatic architecture, and it is the region’s second-largest source of development assistance. The lack of a Japanese military presence and the country’s aversion to contention over security issues actually help highlight these advantages, in contrast with South Korea, where Tokyo still generates distrust.

Southeast Asian countries view Japan in a positive light due to its economic profile and its efforts to engage with partners.

Like China, India shares a border with Southeast Asia and sits astride its sea lanes (through the Indian Ocean). Also like China, it has historical and cultural ties with the region going back centuries. It often calls attention to these connections in its diplomacy. India updated its posture toward the region first in 1991 with its “Look East” policy, and again in 2014 with “Act East.” The impact of both on the region, however, has been minimal.

While India has engaged ASEAN diplomatically, in terms of economic involvement it lags far behind all the other outside powers, and therefore holds less sway. It does have significant naval power, and its ships occasionally transit the region or are anchored nearby. However, it uses these assets cautiously and sparingly.

Collectively, Europe is by far the biggest external investor in Southeast Asia, its second-largest trading partner and a consistent promoter of economic ties. It is also the region’s leading aid donor. It has been able to highlight these strengths through involvement in ASEAN’s regional diplomacy. The EU is an ASEAN “dialogue partner” and part of the annual ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). France and the United Kingdom have separately expressed interest in joining the annual East Asian Summit. France, in fact, given its consistent naval presence, could be a candidate for inclusion in the ADMM-Plus (the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting, including partners).

France and the UK are the only European countries that have real military commitments in the region. France has permanent naval assets in the Pacific and Indian Oceans and deploys as many as four ships a year to demonstrate international rights in the South China Sea. The UK is part of the Five Powers Defense Arrangements – a limited near 50-year-old partnership that also includes Singapore, Malaysia, New Zealand and Australia. It maintains a logistics facility in Singapore. Like France, it has also made demonstrations of international rights to the South China Sea, although fewer.

Scenarios

In light of the above, how will great power competition play out in Southeast Asia and what impact will it have on the broader Indo-Pacific order? There are many variables involved, but the U.S. is the key factor in answering this question.

Scenario 1: Continued U.S. protectionism

In the first, most likely scenario, the view that international trade is negative and that formal trade agreements – especially multilateral ones – are undesirable will continue to dominate U.S. policymaking. This protectionist impulse will have several direct effects on the region.

First, it will continue to reduce American influence. The U.S. cannot match government-directed Chinese investment. It can best bring its enormous economic assets to bear through rule-setting. That is what TPP was about. Without such initiatives, U.S. trade and investment in the region will suffer.

Second, Washington’s aggressive approach is not so much moving supply chains away from China as helping to reshape them. Some American investment is being diverted to Vietnam or Malaysia, but so is Chinese investment. The trading relationships between China and these new investment destinations remain.

Third, the new U.S. approach to trade is not just about China. The administration is also aggressively addressing what it sees as imbalances with other states in the region, like Thailand. This sort of approach will push countries there to look for economic alternatives, including, where possible, China.

In the meantime, other players, like Japan and Europe, will increase economic engagement in Southeast Asia. Overall U.S. influence in the region will decline. If the U.S. maintains the Trump administration’s commitment to defense spending, it will remain a critical security partner in the short to medium term. Over time, however, that role will be eclipsed by broader shared interests between China and ASEAN and American allies’ preference for peaceful development. Without the U.S., the UK will not actively engage militarily. The French will, but carefully, and the Chinese will dismiss their operations as being of little significance. The U.S. will be marginalized and its impact on regional order thwarted.

Countries in the region will continue to court Japan, Europe and India, but without the U.S., their influence on the order there will diminish. The result will be a vicious cycle: With the U.S. less economically invested, it will see less reason for security commitments. The U.S. will gradually withdraw and the Chinese will gain dominance.

Scenario 2: American turnaround on trade

The second scenario involves a less likely turnaround in American sentiment on trade. In this chain of events, the U.S. takes a more conciliatory approach to trade with China. It rallies its partners from Europe and Japan, joins in multilateral tie-ups like the CPTPP and takes a lead in further developing rules. These moves increase its influence in the region. In this context, its military presence – bolstered by increased cooperation with local navies and other outside powers like France and the UK – is sustainable. Furthermore, the French would become even more active at sea and the British would establish a new permanent base in the region – in Japan or Australia. Under these circumstances, China’s influence is tempered. It is forced to come to grips with relatively united perspectives from Southeast Asia’s biggest outside stakeholders, including the EU and Japan.

Scenario 3: Muddling through

The third scenario involves a muddling through and potential black swan events. The decline in U.S. influence will be gradual. European concerns will intensify as Chinese influence grows, not only in Southeast Asia, but elsewhere – in the South Pacific, Africa, and Europe. In Japan, worries about China’s broader influence, particularly in Northeast Asia, will also increase.

China’s position on India’s northern border and off its coasts, as well as its close relationship with Pakistan, will prompt India to engage more seriously in Southeast Asia. The U.S. will cobble together initiatives like it is doing now: joint exercises with the British in the South China Sea, joint patrols with the Japanese, multilateral exercises involving regional partners and the French. It will continue to cooperate with its partners, both operationally and diplomatically.

Under the first scenario, this effort runs its course as U.S. influence declines. In the third scenario, China’s economy collapses, or Beijing becomes a pariah by invading Hong Kong, gets bogged down in an invasion of Taiwan, or sparks a conflict in the South China Sea. All these eventualities will better dispose Southeast Asia to the U.S. and other outsiders by default. The region will reorient itself accordingly and Chinese influence will recede.