Can India bank on its banks?

As the ratio of nonperforming assets in India’s banking sector rises, there have been loud calls for reform. The condition of loan portfolios at state-controlled banks is now so parlous that it is choking off the availability of new credit and forcing the government into ever more ambitious recapitalization schemes.

In a nutshell

- Careless corporate lending has gotten Indian public sector banks in trouble

- The government has mainly responded with massive capital injections

- More serious structural reforms have been hamstrung by political considerations

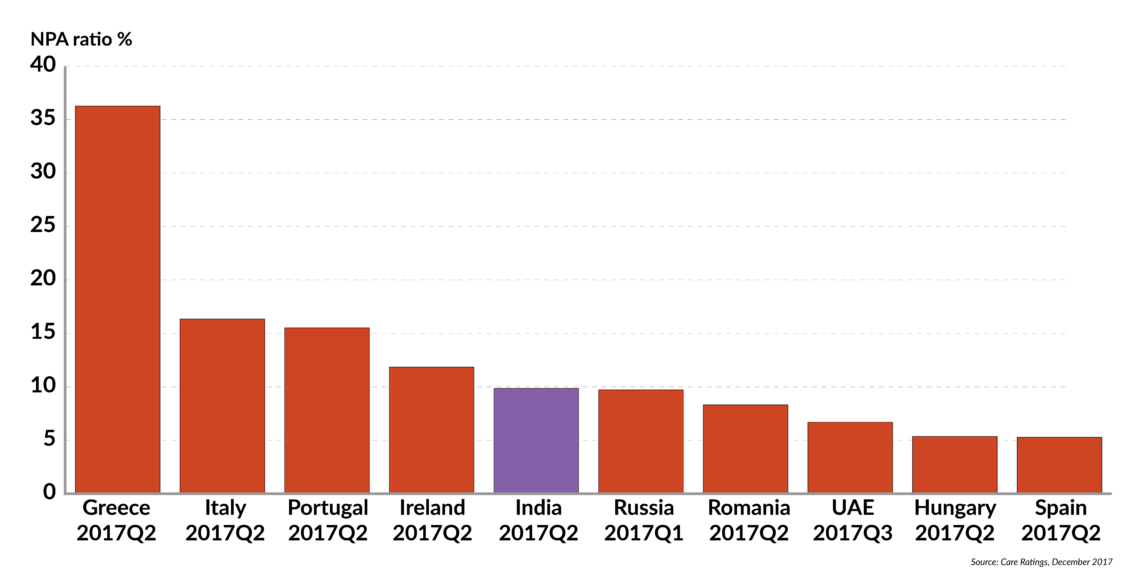

The deepening crisis in India’s banking sector reflects the slow and shallow character of economic reforms over the past 30 years. Today, 10.2 percent of the credits advanced by Indian banks have gone bad – more than double the global average of 3.9 percent, as computed by the World Bank. The latest Financial Stability Report by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) identifies $150 billion in outstanding loans as “stressed” (the figure includes restructured debt that is no longer classified as nonperforming). Both numbers are expected to keep rising.

Globally, India is among the world leaders among economies with the highest ratio of nonperforming assets (NPAs) – in fifth place, according to a ranking by the Mumbai-based CARE Ratings agency. It is expected to bump Ireland (11.9 percent) and move into fourth place on the table in 2018.

The Indian banking sector consists of 21 public sector banks (PSBs) and 56 regional rural banks (RRBs), which are controlled by the state-owned PSBs. In addition, there are 26 domestically owned private banks and 43 foreign banks. In all, that is less than 150 banks in a country of 1.2 billion people. The United States, by contrast, is home to about 7,600 commercial banks, and even Switzerland has more than 250.

The PSBs dominate retail banking, accounting for 70 percent of total deposits. Over the past decade, the ratio of stressed to total loans by Indian banks has worsened sharply – with state-controlled banks accounting for virtually the entire deterioration. The Reserve Bank of India forecasts that NPA ratios will increase this year to more than 15 percent of state-owned banks’ loan portfolios, but less than 4 percent for private banks (under the baseline scenario).

The growth of nonperforming assets has limited the ability of Indian banks to make new loans. Corporate India is already too leveraged, with an aggregate debt of $530 billion. A Credit Suisse analysis found that 40 percent of indebted companies do not make enough operating profit to keep up with their interest payments. Many are already saddled with overcapacity and have no need for fresh loans and investments. The number of new investment projects planned for 2017-2018 is set to be at the lowest in more than a decade, according to a study by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a Mumbai-based think tank.

India’s growing sovereign and corporate debt has choked off the availability of credit.

The steady slowdown in economic growth over six successive quarters in 2016 and 2017, coupled with disruptions in domestic demand, has not helped. Over the past seven years, India’s “twin balance sheet” problem with sovereign and corporate debt has only worsened.

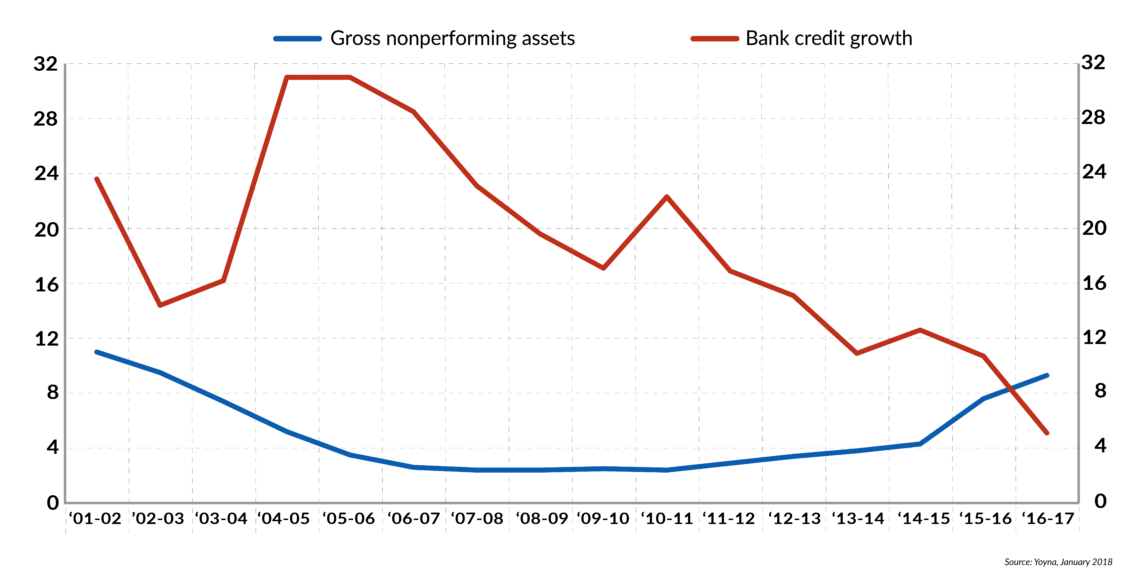

The combination has choked the availability of credit, which dipped to a low of 3.3 percent in early 2017 before increasing over the past six months. The overall profitability of commercial banks has declined since 2013 – due almost entirely to a plunge among public sector banks. Their return on equity (ROE) fell from 12 percent to negative 2 percent over this period, while domestic and foreign private banks maintained relatively healthy ROEs of 11.9 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

The deteriorating balance sheet of PSBs is a growing problem for state finances, which must already contend with a widening budget deficit, projected to reach 3.5 percent of gross domestic product in the 2017-2018 fiscal year.

Dealing with NPAs

Over the past year, the government has announced a so-called four R’s strategy – Recognition, Recapitalization, Resolution and Reforms – to deal with the state-owned financial sector’s nonperforming assets.

Most bad corporate loans are made to industry. The ratio of gross NPAs and stressed advances to industrial borrowers jumped to 19.3 percent and 23.9 percent, respectively, in 2017, according to the RBI’s Fiscal Stability Report. Almost all branches of industry are affected, with metals, engineering and construction among the hardest hit. By contrast, loans to agriculture and services are three or four times less likely to turn bad.

NPAs are defined as loans with overdue payments of 90 days or longer. Loans can go bad for many reasons, including misguided business decisions, failure to anticipate the business cycle, operational risks and changes in the economic environment or government policy. More troubling and systemic issues include corruption, fraud and moral hazard stemming from government ownership.

Facts & figures

Breaking bad

Indian bank lending and nonperforming assets (% growth)

There is also a peculiarly Indian classification (though the behavior itself is more universal) called the “willful defaulter.” These are typically owners of companies who fail to repay loans, even when they have the financial ability to do so. Sometimes these corporate deadbeats expect a bailout because they are too big to fail, and sometimes they hope to be protected by cronyism – the fabled nexus between Indian bureaucrats, businesses and politicians.

Identifying a willful defaulter is no easy task. The RBI has repeatedly refused to name the leading offenders, each of whom owes more than 5 billion rupees ($77.2 million) to the banks. Last year, the central bank told India’s Supreme Court that there were 9,339 cases of willful default, involving a combined sum of Rs1.12 trillion ($17.3 billion).

Recapitalizing PSBs

To enable the state-owned banks to keep lending, successive governments have recapitalized them almost every year since the 1980s. However, the pace of financing has sharply accelerated over the past decade. Since 2008, the government has pumped about Rs1.5 trillion ($23.2 billion) into the PSBs. This capital infusion has helped them meet the capital adequacy ratios set down under Basel III, but the underlying performance of these state-owned lenders has not improved.

The lack of transparency about write-offs at state banks raises many questions about the credibility of the process.

Now the government has decided on an even larger bailout of Rs2.11 trillion ($32.6 billion) over just a two-year period. This amounts to a whopping 1.3 percent of India’s GDP. About Rs800 billion of this capital increase will come in the first quarter of this year, and take the form of non-tradable bonds. An additional Rs81.4 billion will come in direct payments from the budget. Total recapitalization for the 2017-2018 fiscal year should exceed Rs1 trillion, including via equity sales to foreign investors. The rest will be paid in 2018-2019.

The program to recapitalize PSBs is being accompanied by an increase of bad-loan write-offs, even as banks pursue ways to recover whatever is possible. The lack of transparency about these write-offs at state banks raises many questions about the credibility of the process.

Facts & figures

Crisis response

The government and the Reserve Bank of India responded to the banking crisis with a series of regulatory steps and legislative initiatives:

- The RBI tightened regulations on reporting and monitoring by commercial banks, while seeking stringent penalties against inaccurate disclosures and fraud

- Some public sector banks may soon come under the RBI’s prompt corrective action (PCA) procedure, which may be triggered when minimum capital adequacy ratios (CAR) are not met, net NPAs rise above 6%, or the return on assets is negative for two years

- Other government measures include banking and bankruptcy reforms, management reshuffles, and striking shell companies off the records

- The Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill (2017) seeks to bolster banks while offering some relief to depositors

- The Fugitive Economic Offenders Bill (2018) is intended to aid prosecutions of those who have fled the country after allegations of corruption, willful default, money laundering, etc. It provides for the issuance of international arrest warrants and confiscation of assets before conviction

- The National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA) is a new watchdog body to regulate auditors. It was originally mandated in the 2013 Companies Act, but never implemented

But if the past is any guide, stricter regulations, without the capacity to monitor or changes in the incentive structure, are more prone to human failure. Personnel either get too stretched trying to keep up with complex procedures, or the people entrusted with enforcing regulations get tempted to exploit gaps in the system.

Resolution and recovery

Even after three decades of economic liberalization, it is very difficult to close or exit a nonviable business in India. An alphabet soup of acronyms has been generated as governments and banks struggled to find a way to deal with compromised loan portfolios. Typically, this meant debt restructuring, which left corporate and bank management virtually untouched. Resolution has become less effective, as the NPA rate of recovery declined from 22 percent in 2013 to 10 percent last year.

In 2016, the government adopted the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) to consolidate a plethora of earlier efforts to facilitate entrepreneurship, ensure availability of credit and balance the interests of all stakeholders. While liquidation is one of the options, the IBC looks at all possible options for resolving insolvency.

According to India’s central bank, as of November 2017, over 4,300 applications for bankruptcy and insolvency were filed in the various local benches of the National Company Law Tribunal. The data show that operational creditors, such as trade suppliers or employees, have been the most aggressive in initiating corporate insolvency proceedings, followed by financial creditors.

Facts & figures

Business model: SBI

In 2017, the State Bank of India (SBI) became one of the world’s 50 largest banks after it merged with six smaller public sector banks. With over 400 million accounts and 20 percent of all deposits and loans, it is said that the SBI is a barometer of India’s economic health.

2017 was a turbulent year for India’s biggest bank. It recorded a net loss of Rs24 billion ($370.5 million) in the quarter ending on December 31, compared with a Rs18 billion profit a year earlier – mainly due to higher provisioning for nonperforming assets.

Even this overstates the SBI’s performance, which depended heavily on income generated by Rs17 billion in penalties (levied between April and November 2017) on account holders failing to hold a minimum balance of Rs3,000 ($47). The bank also benefited from 22 percent of the total capital given public sector banks by the government in 2008-2017.

After all that largesse, the SBI’s market capitalization today is only half that of India’s largest private lender, HDFC Bank.

The RBI has identified 12 large corporate borrowers – each owing more than Rs50 billion ($771 million), and with an overall debt of over Rs2.4 trillion ($37 billion) – for resolution under the IBC. Another 28 corporate borrowers are being referred as well. The IBC provides a time-bound resolution framework of 180 days, which may be extended by 90 days. The deadline for the 12 most indebted borrowers expired at the end of February and was extended.

The government has high expectations for the IBC to hit the ground running, This risks disappointment, since the implementation of the law needs time to be worked out in practice, as institutions develop procedures and personnel gain experience.

India’s political constraints raise doubt that the insolvency code will offer a viable exit for troubled businesses.

To make matters more complicated, the IBC has already been amended once, with more changes expected. There are questions regarding both the procedure’s transparency and the credibility of some professionals involved. For listed companies, the debt disclosure norms need changing, too.

Given the long history of constraints applied by India’s political economy, one cannot be too confident that IBC will open a viable exit for troubled businesses. The owners of some companies under the insolvency process have already started litigation with bidders for their assets, and more such disputes are likely.

Bail-in outcry

Another government initiative to resolve the NPA problem is the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance (FRDI) bill, now under review by a parliamentary committee. This measure aims for a systematic resolution for all financial firms, whether they be commercial lenders, insurers or other financial intermediaries.

Introduced last year, the FRDI bill became mired in controversy over its “bail-in” clause, despite official claims that 95 percent of depositors would not be affected. In contrast to bailouts, when governments use taxpayers’ money to rescue banks, bail-ins require creditors and depositors to foot at least part of the bill.

Facts & figures

Bank fraud

India’s biggest bank fraud case emerged in mid-February, when two diamond merchants were accused of defrauding the Punjab National Bank, the country’s second largest PSB, of about $2 billion. The accused left the country several months ago and deny any wrongdoing. At least seven officials of the bank, including a senior internal auditor, have been detained in connection with the case.

Another major PSB, the Bank of Baroda, was found to have been involved in dubious business deals with the controversial Gupta family, close associates of former South African President Jacob Zuma, through its Johannesburg branch, which has now been shut down.

In 2012-2017, the RBI reports 8,670 cases of fraudulent loans totaling Rs612.6 billion ($9.46 billion) involving PSBs. Typically, the cases involve borrowers giving false information in their applications and then failing to repay the loans. Indian banks lost Rs239 billion to fraud in 2016-2017, according to RBI data, with 86 percent of that total relating to loans.

More often than not, these crimes are made possible by collusion with bank officials. More than 5,000 employees of PSB’s were convicted or penalized for fraud between January 2015 and March 2017.

The prospect of a bail-in set alarm bells ringing among many bank customers, who discovered that only up to Rs100,000 ($1,543) of their savings would be covered by deposit insurance in case of bank failure. The draft FRDI bill does not specify any new cap on deposit insurance coverage.

With few alternative ways to protect their savings, the outcry from depositors is understandable. Traditionally, gold and real estate have been traditional safe investments, but the authorities have long tried to discourage both.

With only a year to go before the next general election, the FRDI legislation appears destined for the back burner. Only a brave government would risk juggling a hot potato like the bail-in provision.

Structural reforms

Recently, the government’s chief economic advisor, Mr. Arvind Subramanian, suggested that the situation of state-owned lenders called for radical measures. He urged that PSB’s be privatized, reversing Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s forced nationalization of the country’s 14 largest commercial banks in 1969.

While successive capital infusions have increased the government’s massive ownership stake in PSBs, their equity value is less than half that of private sector banks. Since they hold 2.5 times the assets of private banks, this is a telling gauge of how their loan portfolios have deteriorated.

Facts & figures

Moral hazard

Kingfisher was India’s largest airline until a few years ago. Government policy at the time didn’t allow foreign investment in civil aviation. With accumulated debt of more than Rs100 billion and frozen credit lines, the carrier went under.

Today, Kingfisher’s creditors are struggling to sell real estate once owned by the defunct airline to recover their losses. Kingfisher’s founder and main shareholder, Vijay Mallaya (also a member of India’s upper house of parliament), left for London weeks before the creditors closed in.

On the other hand, state-owned Air India, once the country’s sole passenger airline, is now among the country’s most indebted companies. It has Rs500 billion in outstanding loans and unpaid bills of another Rs200 billion. Air India’s market share has fallen to 13 percent, with little chance of a turnaround. Yet it has gotten Rs250 billion from the government over the past few years and still can find credit to operate – presumably because of the implicit sovereign guarantee that it enjoys.

The contrasting fates of these two companies illustrate the privileges enjoyed by India’s public sector. The government prefers to protect public sector banks and companies to preserve its power of patronage and influence. This implied sovereign guarantee makes taxpayers responsible for the business mistakes encouraged by public ownership.

Some government officials have suggested setting up a “bad bank” to absorb all the nonperforming assets, thus relieving pressure on the balance sheets of state-controlled lenders and clearing the way for their privatization. But capitalizing such a bad bank would require an estimated $90 billion-$100 billion, and finding that kind of money would be a challenge for any government.

Outlook

The difficulty with privatizing public sector banks is that they play such a key role in many government programs – including providing hidden subsidies through their lending practice. Through PSBs, the government exercises control over investment financing, giving it direct and indirect influence over public and private companies.

However, this influence is diminishing as the condition of state-controlled commercial banks worsens. Their share of India’s credit market would fall to 40 percent by 2020, from 70 percent in 2010, according to the ICRA ratings agency (partly owned by Moody’s Investors Service). The days of PSB dominance are clearly numbered as the significance of banks as the principal source of credit declines. Private banks, nonbanking finance companies, mortgage banks, technology-based lenders and microfinance institutions are all increasing their share of the market.

With an election around the corner, demands for an implicit sovereign guarantee on bank deposits are likely to grow.

With a general election around the corner, public demands for an implicit sovereign guarantee on bank deposits are likely to grow. Under these circumstances, PSBs may evolve into purely savings institutions over the next few years, collecting deposits and investing most of them in secure government bonds. They could also lend to other banks, while gradually moving out of commercial lending entirely.

This would require the government to give up its habit of steering loans toward favored pet projects. It would be odd to expect any politician to voluntarily give up such potent levers of financial control.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government is caught in a dilemma that illustrates the seductive appeal of sovereign guarantees and the moral hazards using public capital to buy political capital. That is why more than 1,000 public sector enterprises – owned by India’s central, state and local governments – continue to exist despite incurring annual losses equivalent to 1 percent of GDP.

Rather than a prelude to reforms, this year’s recapitalization of state-owned lenders will more likely be another example of large-scale public spending for short-term political gain.