Modi changes India’s Kashmir policy

For decades, India’s policy on the contested state of Jammu and Kashmir has been relatively stable, allowing autonomy in the region and seeking an agreement with Islamabad. However, relations with Sunni Kashmiris have increasingly frayed, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has begun to shift its policy radically.

In a nutshell

- India is reshaping the decades-long status quo in Kashmir

- Modi has taken a series of moves to consolidate power there

- India hopes to create a fait accompli, violent responses are likely

Since 2016, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been debating whether India’s policy toward its most restive state, Jammu and Kashmir, was still relevant.

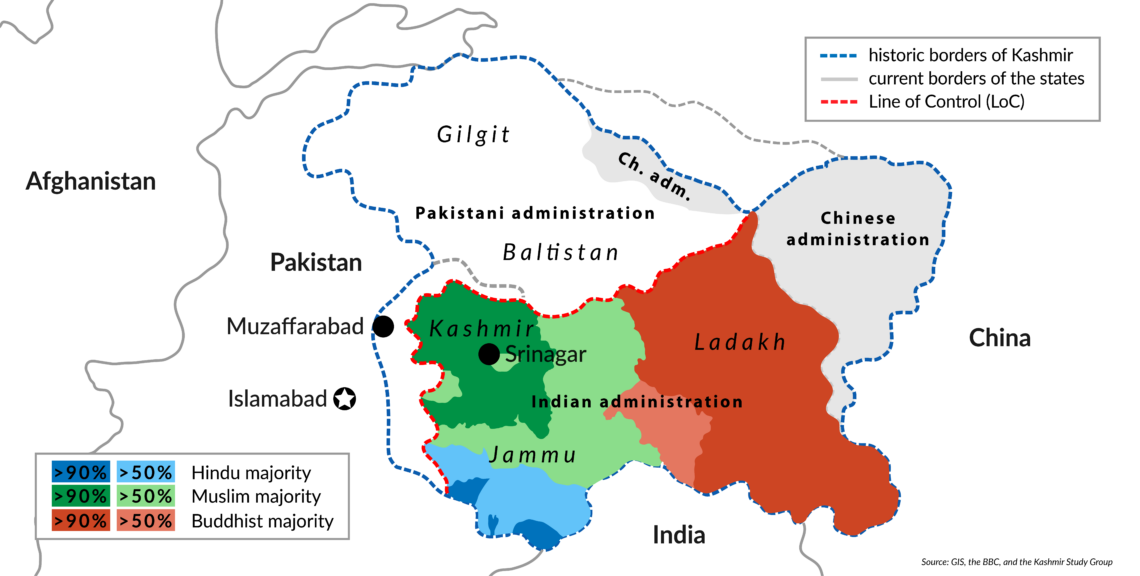

Jammu and Kashmir – a single state that consists of the Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh regions – is at the heart of a long-standing territorial dispute between India and Pakistan, going back to the two countries’ independence in 1947. After decades of diplomatic tussle and three wars, Pakistan controls a third of the state and India holds the remainder.

India’s old policy

From the 1950s on, New Delhi sought an agreement under which Islamabad would accept the territorial status quo and India would provide its Kashmiris with greater political autonomy. Over the past two decades, all Indian governments, including the first prime minister from Mr. Modi’s own right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), tried to secure such a deal. The two sides came tantalizingly close to striking a deal on several occasions.

India’s relationship with the people of Jammu and Kashmir has become increasingly frayed over the years. The Indian part of the state has three distinct parts. Kashmir, the most populous section, is mostly made up of Sunni Muslims who have come to resent the heavy-handed Indian rule deeply. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this resentment (combined with Pakistani assistance) led to an armed insurgency that was crushed only after thousands had died. Sunni Kashmiris remain alienated, as seen through bursts of rioting and sporadic armed attacks.

The second region of the state, Jammu is almost two-thirds Hindu and has become a bastion of BJP support. A third, sparsely-populated section is Ladakh, populated by Shia Muslim tribes and Buddhists.

Sunni Kashmiris remain alienated, as seen through bursts of rioting and sporadic armed attacks.

New Delhi bought peace in Kashmir by four means: it propped up local Sunni parties to serve as a safety valve for Kashmiri sub-nationalism, poured money into the state to keep its economy afloat, allowed Kashmir to dominate Jammu and Ladakh politically, and stationed thousands of soldiers and paramilitaries to ward off Pakistan and deter another insurgency. In the meantime, India fitfully pursued peace negotiations with Pakistan, encouraged on by a worried world.

Things go awry

In its first two years in office, the Modi government went along with this consensus. The BJP’s right wing had long argued that a key reason for the failure of Sunni Kashmiris to see themselves as Indians was the special status that the state of Jammu and Kashmir had been awarded under the Indian Constitution. This status, embodied in the Constitution’s Article 370, gave Jammu and Kashmir the broad right to reject legislation passed by the Indian Parliament in most domestic policy areas. Through derivative clauses, the state also banned non-Kashmiri Indians from owning property in the state.

The Indian security establishment had another concern. In its view, Jammu and Kashmir had developed a “conflict economy” in which insurgents, a corrupt Kashmir political class, and Indian security forces were living off the largesse provided by the central government – and even funds from Pakistan. The state, for example, received more financial assistance from New Delhi than the largest Indian state, Uttar Pradesh, despite having a tenth of the latter’s population. Annual private investment in the state was a pitiful $150 million. None of the players had any interest in ending the state’s low-level violence.

Mr. Modi initially ignored both of these arguments for change. Jammu and Kashmir was largely peaceful the first two years; insurgency incidents in 2018 numbered 614, down from 2,258 in 2009. The BJP even formed a coalition government there with a local Muslim party. The prime minister saw no need to rock a very rickety boat.

In 2016 that policy began to come apart, starting with the BJP’s coalition government in the state, which collapsed. More telling was a three-month-long period of rioting. What was striking was that the youthful Sunni Kashmiri protestors did not invoke the names of their local Indian Kashmiri leaders or even Pakistan – they preferred to raise the banners of the Islamic State and a Muslim caliphate.

Facts & figures

Jammu and Kashmir, by religious group

After his landslide election victory in May, Mr. Modi began to review his country’s Kashmir policy. Other developments, including the rapid weakening of Pakistan, led him to believe he could take radical steps. Skirmishes between the two countries in April had shown Islamabad to be almost friendless in the world. Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) in dollar terms had become smaller than the city of Mumbai.

Moreover, Mr. Modi’s domestic political opposition was in disarray after the elections. Another push was provided by off-the-cuff remarks by United States President Donald Trump about mediating in Kashmir, which led Indian intelligence to argue that the window for a policy change would close by early September. Finally, the government expected stiff challenges in the Supreme Court over its diluting of Article 370, and the makeup of the court’s bench was seen as favorable until October.

New measures

In a series of rapid moves, the Modi government ended Jammu and Kashmir’s special status under the constitution, broke off the Ladakh region, and converted the rest of the state into a centrally-governed territory. It imposed a curfew on the Sunni-dominated areas of Kashmir, shutting down social media and the internet, and placed a few hundred local Kashmiri leaders under house arrest.

Indian officials say these measures are all temporary, driven by a need to avoid significant protests and bloodshed while they rework the state’s political landscape and rebuff the inevitable backlash from Pakistan, whether through diplomacy or terrorism. Less publicly, New Delhi also initiated emergency purchases of air-to-air missiles, long-range artillery shells and other weapons for a worst-case scenario with Pakistan.

What is the blueprint of the “New Kashmir” policy that Mr. Modi has publicly announced? New Delhi is looking to the recent village council and local elections in Jammu and Kashmir to promote a new class of local politicians who, they hope, will focus on economic issues instead of identity. Over the next few months, the electoral districts will be reworked to reflect a demographic shift in favor of Jammu and, as is the practice elsewhere in India, to set aside about 11 percent of seats for tribes and lower-caste residents.

The last stage would be to restore full statehood to Jammu and Kashmir, on a standing equal to other Indian states.

Under this plan, the share of legislative seats held by Sunni Kashmiris would drop to about 47 percent of the total number. Elections would then be held and produce (the BJP expects) a Jammu and Kashmir assembly that would endorse the Modi government’s constitutional changes. With property rights extended to all Indians, the government hopes private business and investors will begin infusing more sustainable wealth into the state. The last stage would be to restore full statehood to Jammu and Kashmir but on a standing equal to the other Indian states.

Scenarios

The Modi government’s preferred outcome is clear: a new Jammu and Kashmir state government in power by the end of 2020, with the older state political leadership marginalized; Sunni Kashmiris prepared to wait for New Delhi’s economic carrots; and the international community waving aside Pakistan’s protests and accepting a new on-the-ground reality.

It is more likely that the next few months will see waves of Sunni Kashmiri protests and possible terrorist attacks. While this will be abetted from across the Pakistani border, much of it will be homegrown. Bloodshed will be inevitable. The best India can hope for is an eventual, sullen acceptance that tolerates the rollout of political reforms. This violence will mean a lot of diplomatic heat. So far, the U.S. has indicated it will look the other way, and even China has made noises only about Ladakh (over which it has minor territorial claims). A new Kashmiri political class may emerge, but genuine change will take a generation.

The nightmare scenario is that violence in Kashmir, including external terrorist activity, overwhelms the Indian government’s ability to carry out its political agenda. In this scenario, elections are not held, a new state assembly is not created, and what was meant to be a temporary rule by New Delhi becomes a permanent condition. China could then become tempted to join with Pakistan to force Indian policy changes.

None of this would roil mainland India or even Narendra Modi’s political standing; Sunni Kashmiris have little popular support, even among other Indian Muslims. However, a key goal of the new Kashmir policy – converting the dispute from a bilateral one to a unilateral one – would become unsustainable. Ironically, the Indian prime minister could be forced to open negotiations with Pakistan and possibly even China, something he has deliberately avoided doing so far.