Innovation by prohibition?

Europe can again become an important player in the global technology race, but it needs to free its innovation drivers from bureaucratic restrictions and overreach.

One of the European Union’s fundamental objectives has been to create an innovative and globally competitive market. This goal is enshrined in the Treaty of Lisbon of 2007, which provides the framework for the European institutions and the Union’s workings.

Throughout history in the West, markets and competition have been the main engine of innovation. That engine is fueled by human curiosity, creativity, and scientific freedom. Governments have never been drivers of innovation, except when it comes to defense.

Military research spin-offs

Unfortunately, war remains a fact of life for humankind and a force for development. Defense research and development (R&D) work often renders a valuable by-product: ideas that can be explored and exploited commercially to benefit all. The most consequential recent example of such an idea is the internet. It began in the early 1960s when government researchers experimented with remote networking to share information. Research on these networks rapidly progressed in Silicon Valley’s technology hotbed. Some funding came from the Pentagon, which during the Cold War was searching for a communication system that could work after a nuclear attack.

Europe’s regulatory-technocratic suicide

A common communications protocol for the existing networks was established on January 1, 1983 – the official birthday of the modern internet. At that point, the market started working its magic. Today’s Big Tech companies have not emerged from government planning and subsidies but from entrepreneurial courage, creativity, competition and markets.

The United States makes an interesting case as it strives to keep its armed forces supreme over all potential adversaries to be able to intervene globally. This diligence, in addition to two oceans and friendly immediate neighbors, serves to protect the American mainland and perpetuate Washington’s hegemonic position. Another example is Israel – one of the most innovative countries. Military and civil development and innovation are driven by the unrelenting threat from its neighbors to Israel’s very existence. In turn, China’s massive innovation push stems from the country’s overarching ambition to lead in the global power competition. The Chinese leaders realize that political and economic prominence must have a robust military foundation.

Innovative drives, through either peaceful competition or war constitute an essential ingredient for preserving a country’s regional and industrial position.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) Critical Technology Tracker finds that China’s global lead extends to 37 out of 44 technologies that ASPI has been following. The technologies cover a range of fields spanning defense, space, robotics, energy, the environment, biotechnology, artificial intelligence (AI), advanced materials and critical aspects of quantum technology. In the remaining areas, the U.S. leads. Europe is not in the picture.

According to ASPI, China’s lead is bolstered through aggressive talent and knowledge acquisition: one-fifth of its high-impact papers are authored by researchers with postgraduate training in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the U.S.

Great European inventions

In its effects, geographical expansion is like war. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, when European ships began sailing across the oceans exploring the Americas and Australia and opening trade routes to Asia, astronomy and navigation techniques made tremendous progress. Science established that the world is not flat, and narrative astrology was replaced by astronomy. Undergirded with mathematics, all this made cross-ocean navigation possible. That, in turn, produced incentives for improved shipbuilding and navigation tools and other refinements. Contemporary space programs have triggered similar effects.

Such innovative drives, through either peaceful competition or war – the most brutal form of competition – constitute an essential ingredient for preserving a country’s regional and industrial position.

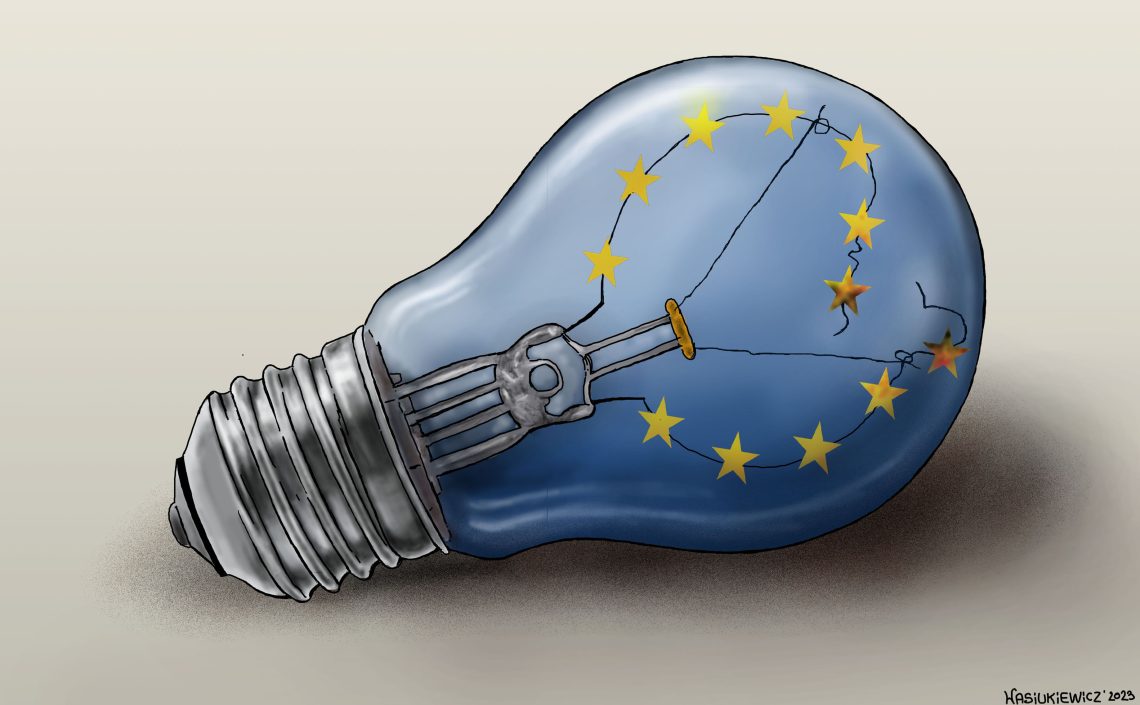

Strangely enough, even though competition is one of the pillars of the European internal market, its primacy as the driver of innovation seems to have been lost in national governments and the European Commission. Policymakers are trying to promote innovation by prohibition instead.

Straying off course

What do we mean by that? Look at how the German government (and others) plans to forbid new heating devices based on fossil fuels. They see the ban as a driver for green innovation and a shift to electricity use. And there will be, of course, funds earmarked for that. From the standpoint of ecology and supply security, it may make sense to reduce Europe’s dependence on fossil fuels. But outlawing such fuels is a bureaucratic overreach.

We do not drive cars because governments outlawed horses, and we do not enjoy electric lighting because governments banned candles.

Whether that strategy will succeed is questionable, as sufficient electric energy generation is already a problem. A similar case is an attempt in Europe to set deadlines for ending the use of internal-combustion engines in motor vehicles. If we allowed competition to do the work, more economical and efficient solutions would be found as prices of fossil fuels inevitably go up.

The decree from institutions might lead to unintended consequences, as substitutes might need more time to be ready and efficient. It is also likely to drive investment in the wrong direction. Such misallocation of resources will lead, on the one side, to wasteful bubbles and zombie businesses, while on the other it will create investment gaps.

The list of innovations that prompted positive disruptions without government participation is very long. We do not drive cars because governments outlawed horses, and we do not enjoy electric lighting because governments banned candles. Modern word processing developed without the prohibition of typewriters. The transition in those and a great many other cases was smoother and less wasteful as the markets tested different varieties.

Think big!

Europe has another problem: the question of competitive critical mass. The European antitrust law has not been designed to serve under global conditions. It is locally focused and Eurocentric. As a result, promising businesses will not grow large enough to be globally competitive. This – and overregulation – prevents Europe from competing with the U.S. and China in technology.

The ideas of Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton to contain the U.S. and Chinese Big Tech by regulation and thus make room for European solutions will fail. The regulatory limits will frustrate European efforts globally. The continent may end up as a protective and mediocre “fortress Europe.”

Unfortunately, Europe is making the same mistake China made in the 19th century. The Chinese leaders believed their civilization was so vastly superior that it did not need to compete with foreign countries. This arrogance led to the Middle Kingdom’s decline, culminating in the plundering of the Forbidden City during the Second Opium War in 1860 by British and French soldiers. China learned its lesson.

However, not all is lost. Europe can still regroup and join the fray as new technologies open huge fields. For that, the continent’s competitiveness must be revived. It is necessary to think about market forces and global impact, and not government attempts to lead with bans and regulations.